Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Reserve Bank of India released the financial stability report on June 27, 2013. The page 14 of the points out “Gross Domestic Saving as a proportion to GDP has fallen from 36.8 per cent in 2007-08 to 30.8 per cent in 2011-12.”

In the year 2004-2005, the total domestic savings had stood at 32.4% of the gross domestic product. Hence, there has been a tremendous drop in savings during the time the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) has governed this country. And this as we shall see is one number that is a broad representation of all that is wrong with the Indian economy in its current state.

The total amount of money that a country saves essentially comes from three sources: households, the private corporate sector, and the public sector. The worrying thing here is that household savings have fallen dramatically during the last seven years.

As the Economic Survey released in February 2013 pointed out “On average, households accounted for nearly three-fourths of gross domestic savings during the period 1980-81 to 2011-12. The share declined somewhat in recent years, and in the period from 2004-05 to 2011-12, it averaged 70.1 per cent of total savings.”

The other worrying factor is the dramatic fall in financial savings, which have pushed down overall domestic savings as well. As the RBI report points out “A large part of this decline has been due to fall in financial savings of households which have declined from 11.6 per cent of GDP to 8 per cent of GDP over the corresponding period (i.e. between 2007-08 to 2011-12.” Financial savings essentially accounts for savings in the form of bank deposits, life insurance, pension and provision funds, shares and debentures etc. In fact between 2010-2011 and 2011-2012, the household financial savings fell by a massive Rs 90,000 crore.

So the question is why have households savings and within them household financial savings, fallen so dramatically over the last few years? A straight forward answer is high inflation. The high inflation that has plagued the country during the course of UPA’s second term has meant that people have had to spend more money to buy the same basket of goods as they were doing the same. And this has meant lower savings. What this also tells us is that newspaper stories that talk about salaries in India going up in double digit terms, need to be taken with a pinch of salt, given that inflation has also more or less gone up at the same rate.

Also high inflation has meant that the real rate of returns after adjusting for inflation on products like public provident fund, bank deposits and post office deposits, which pay out a fixed rate of interest every year, have gone down. In fact, a fixed deposit paying an interest of 8-9% per year currently has a negative real rate of return in an environment where the consumer price inflation is greater than 9%. “Much of the financial savings of the household sector are in the form of bank deposits (around 30 per cent in the 2000s)..These were also the years when the real rate of interest was generally declining,” the Economic Survey pointed out.

In such an environment a lot of money has gone into gold and real estate which had a prospect of giving higher returns. As the Economic Survey pointed out “The last three years have seen a substantial rise in gold imports (the value of gold imports increased nine times between January 2008 and October 2012)…Gold imports are positively correlated with inflation.” High inflation reduces the ‘real’ return adjusted for inflation on other financial instruments and leads to people buying gold.

Given that a lot of savings have gone into gold and real estate, this has pulled down overall financial savings. As financial savings have fallen dramatically the interest rates on loans has been high for the last few years. In fact this is one reason why Indian businesses have been borrowing a lot of money abroad rather in India over the last few years. As the Business Standard reports “Beginning 2004, the central bank(i.e. RBI) has approved nearly $220 billion worth of external commercial borrowings and foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCB), at the rate of a little over $2 billion a month. Nearly two-thirds of this amount was approved in the past five years.”

Both gold and external borrowings have added to India’s dollar problem. India produces very little gold. Hence, almost all the gold that is consumed in the country is imported. Gold is bought and sold in dollars internationally. And every time an Indian importer buys gold, dollars are needed. This pushes up the demand for dollars in the market and puts pressure on the rupee. Gold imports are one reason why the rupee has lost value against the dollar through much of this year.

The finance minister P Chidambaram has been asking people time and again not to buy gold, without addressing the basic problem of “inflation”. Gold is finally just a symptom of the problem i.e. inflation. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy,” the Economic Survey pointed out.

As far as foreign borrowings by Indian businesses are concerned, they need to repaid. To do this, Indian businesses will have to sell rupees and buy dollars, and this will push up the demand for dollars and put further pressure on the rupee. As the Business Standard points out “Much of this external commercial borrowing will come up for repayment this financial year, putting further pressure on the rupee.”

So financial savings going down due to inflation has created several problems for the country. Another reason for the financial savings being hit is the tremendous mis-selling of insurance by insurance companies. The RBI report says that the “credibility of the financial institutions” has been hit “in the wake of mis-selling of products and financial frauds”. The government hasn’t been able to do much on this front as well.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on June 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Dollar

Rupee fall: Why India's struggle for dollars will continue

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The question being asked yesterday was “why is the rupee falling against the dollar”. The answer is very simple. The demand for American dollars was more than that of the Indian rupee leading to the rupee rapidly losing value against the dollar.

This situation is likely to continue in the days to come with the demand for dollars in India being more than their supply. And this will have a huge impact on the dollar-rupee exchange rate, which crossed 60 rupees to a dollar for the first time yesterday.

Here are a few reasons why the demand for dollars will continue to be more than their supply in the days to come.

a) The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) recently pointed out that

the foreign direct investment in India fell by 29% to $26 billion in 2012. When dollars come into India through the foreign direct investment(FDI) route they need to be exchanged for rupees. Hence, dollars are sold and rupees are bought. This pushes up the demand for rupees, while increasing the supply of dollars, thus helping the rupee gain value against the dollar or at least hold stable.

In 2012, the FDI coming into India fell dramatically. The situation is likely to continue in the days to come. The corruption sagas unleashed in the 2G and the coalgate scam hasn’t done India’s image abroad any good. In fact in the 2G scam telecom licenses have been cancelled and the message that was sent to the foreign investors was that India as a country can go back on policy decisions. This is something that no big investor who is willing to put a lot of money at stake, likes to hear.

Opening up multi-brand retailing was government’s other big plan for getting FDI into the country. In September 2012, the government had allowed foreign investors to invest upto 51% in multi-brand retailing. But between then and now not a single global retailing company has filed an application with the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), which looks at FDI proposals.

This scenario doesn’t look like changing as likely foreign investors struggle to make sense of the regulations as they stand today. Dollars that come in through the FDI route come in for the long run as they are used to set up new industries and factories or pick up a stake in existing companies. This money cannot be withdrawn overnight like the money invested in the stock market and the bond market.

b) There has been a lot of talk about the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) selling bonds to Non Resident Indians (NRIs) and thus getting precious dollars into the country. The trouble here is that any NRI who invests in these bonds will carry a huge amount of currency risk, given the rapid rate at which the rupee has lost value against the dollar.

Lets understand this through a simple example. An NRI invests $100,000 in India. At the point he gets money into India $1 is worth Rs 55. So $100,000 when converted into rupees, amounts to Rs 55 lakh. This money lets assume is invested at an interest rate of 10%. A year later Rs 55 lakh has grown to Rs 60.5 lakh (Rs 55 lakh + 10% interest on Rs 55 lakh). The NRI now has to repatriate this money back. At this point of time lets say $1 is worth Rs 60. So when the NRI converts rupees into dollars he gets $100,800 or more or less the same amount of money that he had invested. His return in dollar terms is 0.8%. The real return would be much lower given that this calculation doesn’t take the cost of conversion into account.

Hence, the NRI would have been simply better off by letting his money stay invested in dollars. This is the currency risk. To make it attractive for NRI investors to invest money in any such RBI bond, the interest on offer will have to be very high.

c) While the supply of dollars will continue to be a problem, the demand for them will continue to remain high. A major demand for dollars will come from companies which have raised loans in dollars over the last few years and now need to repay them. As the Business Standard reports “Beginning 2004, the central bank(i.e. RBI) has approved nearly $220 billion worth of external commercial borrowings and foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCB), at the rate of a little over $2 billion a month. Nearly two-thirds of this amount was approved in the past five years. Much of this ECB will come up for repayment this financial year, putting further pressure on the rupee.”

A lot of companies have raised foreign loans over the last few years simply because the interest rates have been lower outside India than in India. These companies will need dollars to repay their foreign loans as they mature.

The other thing that might happen is that companies which have cash, might look to repay their foreign loans sooner rather than later. This is simply because as the rupee depreciates against the dollar, it takes a greater amount of rupees to buy dollars. So if companies have idle cash lying around, it makes tremendous sense for them to prepay dollar loans. The trouble is that if a lot of companies decide to prepay loans then it will add to the demand for the dollar and thus put further pressure on the rupee.

d) India’s love for gold has been one reason behind significant demand for the dollar. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. India produces very little gold of its own and hence has to import almost all the gold that is consumed in the country. When gold is imported into the country, it needs to be paid for in dollars, thus pushing up the demand for dollars. As this writer has argued in the past there is some logic for the fascination that Indians have had for gold. A major reason behind Indians hoarding to gold is high inflation. Consumer price inflation continues to remain high. Also, with the marriage season set to start over the next few months, the demand for gold is likely to go up. What can also add to the demand is the fall in price of gold, which will get those buyers who have not been buying gold because of the high price, back into the market. All this means a greater demand for dollars.

e) India has been importing a huge amount of coal lately to run its power plants. Indian coal imports shot up by 43% to 16.77 million tonnes in the month of May 2013, in comparison to the same period last year. Importing coal again means a greater demand for dollars.

The irony is that India has huge coal reserves which are not being mined. The common logic here is to blame Coal India Ltd, which more or less has had a monopoly to produce coal in India. The government has tried to encourage private sector investment in the sector but that has been done in a haphazard manner leading to the coalgate scam. This has delayed the bigger role that the private sector could have played in the mining of coal and thus led to lower coal imports.

The situation cannot be set right overnight. The major reason for this is the fact that the expertise to get a coal mine up and running in India has been limited to Coal India till now. To develop the same expertise in the private sector will take time and till then India will have to import coal, which will need dollars.

f) The government’s social sector policies may also add to a huge demand for dollars in the time to come. The procurement of wheat by the government this year has fallen by 33% to 25.08 million tonnes. This will not have any immediate impact given the huge amount of grain reserves that India currently has. But as and when right to food security becomes a legal right any fall in procurement will mean that the government will have to import food grains like wheat and rice, and this will again mean a demand for dollars. While this is a little far fetched as of now, but is a likely possibility and hence cannot be ignored.

These are fundamental issues which will continue to influence the dollar-rupee exchange rate in the days to come and do not have easy overnight kind of solutions. Of course, if the Ben Bernanke led Federal Reserve of United States, decides to go back to printing as many dollars as it is right now, then a lot of dollars could flow into India, looking for a higher return. But then, that is something not under the control of Indian government or its policy makers.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Mr Chidambaram, India's love for gold is just a symptom, not a problem

Vivek Kaul

P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, has been urging Indians not to buy gold. But we just won’t listen to him.

In the month of May 2013, India imported $8.4 billion worth of gold, up by 90% in comparison to May 2012. This surge in gold imports pushed up the trade deficit to $20.14 billion in May. It was at $17.8 billion during April 2013. Trade deficit is the difference between the merchandise imports and exports. Commerce Secretary S R Rao said “As far as trade deficit is concerned, it is very worrisome…It is largely contributed by heavy imports of gold and silver.”

A trade deficit means that the country is not earning enough dollars through exports to pay for all that it is importing. To correct this, it either needs to increase its exports and earn more dollars to pay for imports or cut down on its imports. Indian exports have been growing at a very slow pace. In fact they fell by 1.1% in May 2013 to $24.5 billion. Imports on the other hand rose by 7% to $44.65 billion.

The trouble is that when India imports gold it pays for it in dollars. Indian rupees are sold to buy these dollars. Given this there is a surfeit of rupees in the market and a scarcity of dollars, pushing up the value of the dollar against the rupee. This leads to the country paying more for imports in rupee terms.

Hence, the logic goes that India should not be importing as much gold as it is. Or as Chidambaram said a few days back “I would once again appeal to everyone please resist the temptation to buy gold…If I have one wish which the people of India can fulfill is don’t buy gold.”

But the same logic applies to oil as well. India imported $15 billion worth of oil in May 2013. Of course, oil is more useful than gold, and we need to import it because we don’t produce enough of it.

And given that gold is as useless as something can be, we don’t need to import it. Or as Chidambaram said “I continue to hope and suppose if the people of India don’t demand gold if we don’t have to import gold for a year just imagine the whole situation will so dramatically change. Every ounce of gold is imported. You pay in rupees, we have to provide dollars.”

So what comes out of all this is that the government does not want Indians to buy gold. It recently increased the import duty on gold to 8% from 6% earlier. Chidambaram even set a personal example when he recently said “I don’t buy gold, I put my money in financial instruments and I am happy.”

There are multiple problems with what Chidambaram is saying. The first and foremost is the fact that buying or not buying gold is a free economic decision that people choose to make. Or as economist Bibek Debroy wrote in a column in The Economic Times “The gold policy is futile because buying gold is a free decision of rational economic agents and gold imports are a symptom, not the disease.”

And what is the symptom? The symptom is the high consumer price inflation that prevails. People have been buying gold to hedge themselves against that inflation. As the Economic Survey of the government for the year 2012-2013, released in February pointed out “Gold imports are positively correlated with inflation: High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising imports and falling real rates.”

What this means is that because inflation is high the real rate of return on financial instruments is very low. Why would people invest in a financial instrument like a fixed deposit or a PPF account or a National Savings Certificate, at an interest of 8-9%, when the consumer price inflation is higher than that? So what do they do? They invest in gold because they have been told over the generations, that gold holds its value against inflation.

Chidambaram has asked people not to buy gold and even gone to the extent of saying that he does not buy the yellow metal and puts his money in financial instruments. Of course, being the finance minister of the country he is unlikely to face any problems while investing in financial instruments.

But here is a small suggestion. Chidambaram should try investing in a mutual fund once on his own without going through a bank or an agent. And the bizarre number of requirements that need to be fulfilled to invest in a mutual fund, will give him a real flavour of how difficult it is to invest for an individual to invest in a mutual fund.

Or take the case of a senior citizen who invests his retirement funds in the senior citizen savings scheme run by the post office and is given a thorough run-around every time he has to go and collect the interest on the money that he has deposited.

Or take case of the spate of smses banks recently sent out to their customers asking them to furnish documents and account opening recommendations, even when customers have had accounts for more than a decade.

Given this, it is not surprising that people buy gold which is available hassle free over the counter. The Economic Survey nailed it when it said “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation and the lack of financial instruments available to the average citizen, especially in the rural areas. The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion…and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance.” Hence, people will continue to buy gold when they want to, irrespective of the appeals made by Chidambaram.

Inflation is something that the government of this country has created. And when people protect themselves against it, you can’t hold them responsible for creating other problems.

When a country runs a trade deficit it doesn’t earn enough dollars to pay for its imports through exports. What happens in this situation is that dollars coming in through other sources like foreign direct investment, foreign institutional investment and citizens living abroad, are used to finance imports.

In India’s case remittances a well as deposits made by NRIs play an important part in filling up the trade deficit gap. As Andy Mukherjee points out in a column in the Business Standard “For every rupee of time deposits that Indian banks have raised from residents in the past year, 13

paise has come from the estimated 25 million people of Indian origin who live in other countries.”

World over interest rates on savings deposits are at very low levels. The same is not true about India where interest rates continue to remain high and hence it makes sense for NRIs to invest money in India.

But this investment carries the currency risk. Lets understand this through an example. An NRI decides to invest $100,000 in India. At the point of time he gets his money into India, one dollar is worth Rs 50. So he has got Rs 50 lakh to invest. He invests this in a bank which is offering him 10% interest. At the end of the year he gets Rs 55 lakh (Rs 50 lakh + 10% interest on Rs 50 lakh).

Now lets say a year later $1 is worth Rs 55. So when the NRI converts Rs 55 lakh into dollars, he gets $100,000 (Rs 55 lakh/55) or the amount that he had invested initially. Hence, he does not make any return in the process. This is because the Indian rupee has depreciated against the dollar, which is something that has been happening lately. This is the currency risk.

In this scenario, the NRIs are likely to withdraw their deposits from India because if the rupee keeps losing value against the dollar, chances are they might face losses on their investments. When NRIs repatriate their money, they sell rupees and buy dollars. This leads to a surfeit of rupees and shortage of dollars in the market, and thus leads to the rupee depreciating further.

This is a scenario that is likely to play out in the days to come. Over and above this there is also the danger of foreign institutional investors continuing to withdraw money from the Indian debt market, as they have in the recent past.

This danger has become even more pronounced with Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, announcing late last night that they would go slow on money printing.

As he said “the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year.”

The Federal Reserve prints dollars and uses them to buy bonds to pump money into the financial system. This ensures that interest rates continue to remain low as there is enough money going around.

As and when the Federal Reserve goes slow on money printing, the American interest rates will start to go up (in fact they have already started to go up). Given this the investors who had been borrowing in the United States and using that money to invest in India, would be looking at a lower return as they will have to pay a higher interest on their borrowing.

A prospective lower return could lead to some of these investors to sell out of India. In fact as I write this the bond market has come to a halt because there are only sellers in the market and no buyers. Such has been the haste to exit India.

When foreign investors sell out of bonds (and stocks for that matter) they get paid in rupees. This money needs to be repatriated to the United States and hence needs to be converted into dollars. So the rupees are sold to buy dollars from the foreign exchange market.

When this happens there is a surfeit of rupees in the market and a huge demand for dollars. This has led to the rupee rapidly losing value against the dollar. Around one month back one dollar was worth Rs 55. Now its worth close to Rs 60 ($1 equals Rs 59.9 to be precise).

A lower rupee means that the price of gold is likely to go up in rupee terms. And this can attract more investors into gold pushing up India’s gold import bill further. But then do we blame for the gold investor for that? And if that is the case why not ban all speculation, starting with real estate.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on June 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

As yen hits 100 to US$, get ready for more currency wars

Vivek Kaul

Ushinawareta Nijūnen or the period of two lost decades for Japan(from 1990 to 2010) might finally be coming to an end. Or so it seems.

And Japan has to thank Abenomics unleashed by its current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for it. Abe has more or less bullied the Bank of Japan, the Japanese central bank, to go on an unlimited money printing spree, until it manages to create an inflation of 2%.

The Japanese money supply is set to double over a two year period. And all this ‘new’ money that is being pumped into the financial system, will chase an almost similar number of goods and services, and thus drive up their prices. Or so the hope is.

The target is to create an inflation of 2% and get people spending money again. When prices are rising or are expected to rise, people tend to buy stuff, because they don’t want to pay a higher price later (This of course is true to a certain level of inflation and doesn’t hold in the Indian case where retail inflation is greater than 10%). As people go out and shop, it helps businesses and in turn the overall economy.

In an environment where prices are stagnant or falling, as has been the case with Japan for a while now, people tend to postpone purchases in the hope of getting a better deal. The situation where prices are falling is referred to as deflation.

In 2012, the average inflation in Japan was 0%, which meant that prices neither rose nor they fell. In fact, in each of the three years for the period between 2009 and 2011, prices fell on the whole. This has led people to postpone their consumption and hence had a severe impact on Japanese economics growth. To break this “deflationary trap”, Shinzo Abe and the Bank of Japan have decided to go on an almost unlimited money printing spree.

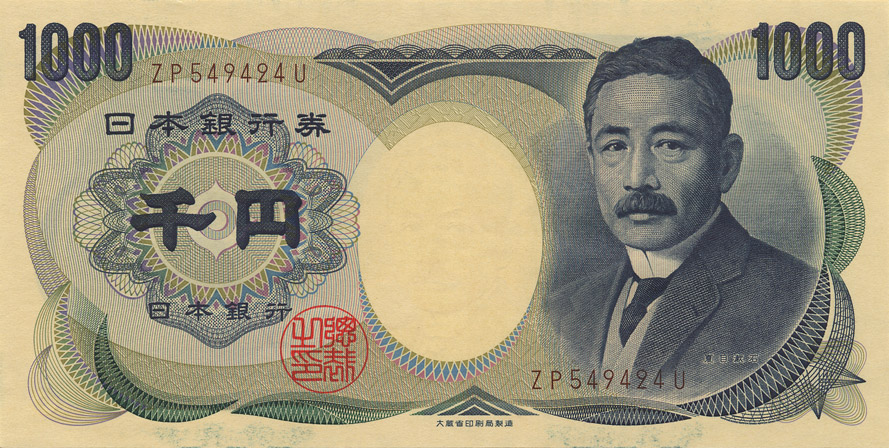

A major impact of this policy has been on the Japanese currency ‘yen’. As more yen are created out of thin air, the currency has weakened considerably against other major currencies. One dollar was worth around 78 yen, on October 1, 2012. Yesterday, yen weakened beyond 100 to a dollar for the first time in four years. As I write this one dollar is worth around 101.1 yen.

This weakening of the yen has helped Japanese businesses which have a major international presence spruce up their profits. As the news agency Bloomberg reports “The weaker yen helped Mazda, Japan’s fifth-largest car company, post a profit of 34 billion yen for the fiscal year that ended March 31, compared with a loss of 107.7 billion yen the previous year. A one-yen change against the dollar, euro, Canadian dollar and Australian dollar has a 9.1 percent impact on Mazda’s operating profit…That compares with 4.7 percent at Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd, which makes Subaru cars, and 3.1 percent at Toyota.”

When yen was at 78 to a dollar, a Japanese company making a profit of $1 million internationally would have made a profit of 78 million yen. Now with the yen at 101 to a dollar, the same company will make a profit of 101 million yen, which is almost 29.5% more.

This increase in profit it is hoped will also encourage Japanese companies to pay their employees more. Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writing in a report titled Thoughts on Asia will a yen slide trigger an EM currency crisis? 1997 redux dated April 17, 2013, cites a survey which suggests that Japanese companies may be short on labour. “This suggests that Prime Minister Abe will indeed get his way on a rapid return of wage inflation to boost consumption,” writes Edwards.

And this boost in consumption will get the Japanese economy going again. So does that mean Japan will live happily ever after? Not quite.

As the Japanese central bank prints more and more yen, the returns from Japanese government bonds are expected to go up. As Edwards writes “if the market really believes that it is committed to the 2% inflation target (and I certainly do), then Japanese bond yields(returns) will quickly attempt a move above 2%.” In early April the return on a ten year Japanese government bond was at 0.45% per year. Since then it has risen to around 0.69% per year.

And this can lead to a major crisis in Japan. If returns on existing bonds go up, the government will have to offer a higher rate of interest on the new bonds that it issues to make them interesting enough for investors.

As Satyajit Das writes in a research paper titled The Setting Sun – Japan’s Financial Miasma “Higher interest rates will increase the stress on government finances. Even at current low interest rates, Japan spends around 25-30% of its tax revenues on interest payments. At borrowing costs of 2.50% to 3.50% per annum, two to three times current rates, Japan’s interest payments will be an unsustainable proportion of tax receipts.”

Now that’s just one part of it. If the government has to spend more of the money than it earns towards interest payments that means there will be less left for meeting other expenditure. So it will either have to borrow more or ask the Bank of Japan to print more money to finance its expenditure, given that there is a limit to the amount of money that can be borrowed. Either option doesn’t sound good. Das estimates that Japan’s gross government debt will reach around 250-300% of its gross domestic product by 2015, a very high level indeed.

Also as things stand as of now it looks like the Bank of Japan will have to finance a major part of Japanese government expenditure in the years to come by printing money. As Dylan Grice wrote in an October 2010, Societe Generale report titled Nikkei 63,000,000? A cheap way to buy Japanese inflation risk “Japan’s tax revenues currently don’t even cover debt service and social security, persistent and growing fiscal burdens. Therefore, once the Bank of Japan is forced into monetisation of government deficits, even if only with the initial intention of stabilising government finances in the short term, it will prove difficult to stop. When it becomes the largest holder and most regular buyer of Japanese government bonds, Japan will be on its inflationary trajectory.” And this is not an inflation of 2% that we are talking about.

The yen weakening against other international currencies is making Japanese exports more competitive. A Japanese exporter with sales of a million dollars in early October, would have made 78 million yen (when one dollar was worth 78 yen). Now the same exporter would make 101 million yen.

The weakening yen allows Japanese exporters to cut their prices in dollar terms and become more price competitive. If a price cut of 20% is made, then sales will come down to $800,000 but in yen terms the sales will be at 80.8 million yen ($800,000 x 101). This will be higher than before. Also a cut in price might help Japanese exporters to increase total volumes of sales.

The trouble of course is that this will hit other major exporters like South Korea, Taiwan and Germany. As Michael J Casey points out in a column on Wall Street Journal website “Japan might be a hobbled economy but it is still the third largest in the world, accounting for almost one-tenth of world gross domestic product. So when the Bank of Japan prints as much yen as this, it provokes a worldwide adjustment in relative prices. Electronics producers in South Korea, Taiwan and, to an increasing degree, China, automatically face a price disadvantage versus their Japanese competitors, for example.”

Also interest rates on American and Japanese bonds are currently at very low levels. And this has sent investors looking for return to other parts of the world. Take the case of New Zealand. Foreign money has been flooding into the country. When foreign money comes into a country it needs to be exchanged for the local currency (the New Zealand dollar in case of New Zealand). This leads to a situation where the demand for the local currency increases, leading to its appreciation.

One New Zealand dollar was worth around 64.6 yen on October 1, 2012. It is currently worth around 84.4 yen. An appreciation in the value of a country’s currency hurts its exports. On Wednesday (May 8, 2013), the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, decided that it will intervene in the foreign exchange market to weaken the New Zealand dollar.

How does any central bank weaken its currency? When a huge amount of foreign money comes in, it increases the demand for local currency. The central bank at that point floods the foreign exchange market with its own currency, to ensure that there is enough of it going around. This ensures that the local currency does not appreciate. If the central bank floods the market with more local currency than the demand is, it ensures that the local currency loses value against the foreign money that is coming in.

The question is where does the central bank get this money from? It simply prints it.

The thing to remember is that if Japan can print money to cheapen its currency so can other countries like New Zealand. It is not rocket science. Its what Americans call a no brainer. In fact, yen started appreciating against the dollar once the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, started printing money to revive economic growth. And this has also been responsible for Japan starting to print money. As Casey points out “Together, the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan will print the equivalent of $155 billion every month for an indefinite period.” This will spill over to more countries printing money to hold the value of their currency or even cheapen it.

The currency war which is currently on between countries as they print money to cheapen their currencies will only get worse in the days and months and years to come. Australia is expected to join this war very soon. Countries are also trying to control the flood of foreign money by cutting interest rates. The Australian central bank cut interest rates on Tuesday (i.e. May 7, 2013). The Bank of Korea, the South Korean central bank also cut interest rates on Thursday (i.e. May 9,2013). China has put measures in place to curb foreign inflows.

As Greg Canvan writes in The Daily Reckoning Australia “So as the US dollar moves above 100 yen for the first time in four years…Get ready for an escalation in the currency wars.”

To conclude, it is important to remember what H L Mencken, an American writer, once said “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” If only creating economic growth was just about printing more money…

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 11, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why the dollar continues to look as good as gold

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few years a mini industry predicting the demise of the dollar has evolved. This writer has often been a part of it. But nothing of that sort has happened.

There are fundamental reasons that have led this writer and other writers to believe that dollar is likely to get into trouble sooner rather than later. The main reason is the rapid rate at which the Federal Reserve of United States has printed dollars over the last few years. This rapid money printing is expected to create high inflation sometime in the future.

But whenever markets have sensed any kind of trouble in the last few years money has rapidly moved into the dollar. In fact, even when the rating agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded America’s AAA status, money moved into the dollar. It couldn’t have been more ironical.

What is interesting nonetheless that the doubts on the continued existence of the dollar are getting graver by the day. Gillian Tett, the markets and finance commentator of The Financial Times has a very interesting example on this in her latest column Is Dollar As Good as Gold published on March 1, 2013.

As Tett writes “Should we all worry about the outlook for the mighty American dollar? That is a question that many economists and market traders have pondered as economic pressures have grown. But in recent weeks Virginia’s politicians have been discussing it with renewed zeal. Last month Bob Marshall, a local Republican, submitted a bill to the local assembly calling on the state to study whether it should create its own “metallic-based” currency.”

The reason for this as the bill pointed out was that “Unprecedented monetary policy actions taken by the Federal Reserve … have raised concern over the risk of dollar debasement.”

In fact Virginia is not the only state in the United States that has been talking about a currency backed by a precious metal(read gold). As Tett puts it “So guffaw at the Virginia bill if you like. And if you want an additional chuckle, you might also note that a dozen other state assemblies, in places such as North and South Carolina, have discussed similar ideas; indeed, Utah has a gold and silver depository which is trying to back debit cards with gold.”

The point is that the debate on the demise of the dollar if it continues to be printed at such a rapid rate, is now moving into the mainstream.

So what will be the fate of the US dollar? Will it continue to be at the heart of the global financial system? These are questions which are not easy to answer at all. There are too many interplaying factors involved.

While there are fundamental reasons behind the doubts people have over the future of the dollar. There are equally fundamental reasons behind why the dollar is likely to continue to survive. But one good place to start looking for a change is the composition of the total foreign exchange reserves held by countries all over the world. The International Monetary Fund puts out this data. The problem here is that a lot of countries declare only their total foreign exchange reserves without going into the composition of those reserves. Hence the fund divides the foreign exchange data into allocated reserves and total reserves. Allocated reserves are reserves for countries which give the composition of their foreign exchange reserves and tell us exactly the various currencies they hold as a part of their foreign exchange reserves.

Dollars formed 71% of the total allocable foreign exchange reserves in 1999, when the euro had just started functioning as a currency. Since then the proportion of foreign exchange reserves that countries hold in dollars has continued to fall. In fact in the third quarter of 2008 (around the time Lehman Brothers went bust) dollars formed around 64.5% of total allocable foreign exchange reserves. This kept falling and by the first quarter of 2010 it was at 61.8%. It has started rising since then and as per the last available data as of the third quarter of 2012, dollars as a proportion of total allocable foreign exchange reserves are at 62.1%. The fall of the dollar has all along been matched by the rise of the euro. But with Europe being in the doldrums lately it is unlikely that countries will increase their allocation to the euro in the days to come. Between first quarter of 2010 and the third quarter of 2012, the holdings of euro have fallen from 27.3% to 24.14%.

So the proportion of dollar in the total allocable foreign exchange reserves has fallen from 71% to 62.1% between 1999 and 2012. But then dollar as a percentage of total allocable foreign exchange reserves in 2012 was higher than it was in 1995, when the proportion was 59%.

So when it comes to international reserves, the American dollar still remains the currency of choice, despite the continued doubts raised about it. One reason for it is the fact that there has been no real alternative for the dollar. Euro was seen as an alternative but with large parts of Europe being in bigger trouble than America, that is no longer the case. Japan has been in a recession for more than two decades not making exactly yen the best currency to hold reserves in.

The British Pound has been in doldrums since the end of the Second World War. And the Chinese renminbi still remains a closed currency given that its value is not allowed to freely fluctuate against the dollar.

So that leaves really no alternative for countries to hold their reserves in other than the American dollar. But that is not just the only reason for countries to hold onto their reserves in dollars. The other major reason why countries cannot do away with the dollar given that a large proportion of international transactions still happen in dollar terms. And this includes oil.

The fact that oil is still bought and sold in American dollars is a major reason why American dollar remains where it is, despite all attempts being made by the American government and the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, to destroy it. And for this the United States of America needs to be thankful to Franklin D Roosevelt, who was the President from 1933 till his death in 1945 (in those days an individual could be the President of United States for more than two terms).

At the end of the Second World War Roosevelt realised that a regular supply of oil was very important for the well being of America and the evolving American way of life. He travelled quietly to USS Quincy, a ship anchored in the Red Sea. Here he was met by King Ibn Sa’ud of Saudi Arabia, a country, which was by then home to the biggest oil reserves in the world.

The United States’ obsession with the automobile had led to a swift decline in domestic reserves, even though America was the biggest producer of oil in the world at that point of time. The country needed to secure another source of assured supply of oil. So in return for access to oil reserves of Saudi Arabia, King Ibn Sa’ud was promised full American military support to the ruling clan of Sa’ud..

Saudi Arabia over the years has emerged as the biggest producer of oil in the world. It also supposedly has the biggest oil reserves. It is also the biggest producer of oil within the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the oil cartel. Hence this has ensured that OPEC typically does what Saudi Arabia wants it to do. Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia has had the almost unquestioned support of what are known as the sheikhdom states of Bahrain, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

In fact, in the late 1970s efforts were made by other OPEC countries, primarily Iran, to get OPEC to start pricing oil in a basket of currencies (which included the dollar) but that never happened as Saudi Arabia put its foot down on any such move. This led to oil being continued to be priced in dollars and was a major reason for the dollar continuing to be the major international reserve currency.

It is important to remember that the American security guarantee made by President Roosevelt after the Second World War was extended not to the people of Saudia Arabia nor to the government of Saudi Arabia but to the ruling clan of Al Sa’uds. Hence, it is in the interest of the Al Sa’ uds to ensure that oil is continued to be priced in American dollars.

And until oil is priced in dollars, any theory on the dollar being under threat will have to be taken with a pinch of salt because the world will need American dollars to buy oil. Also it is important to remember that financially America might be in a mess, but by and large it still remains the only superpower in the world. In 2010, the United States spent $698billion on defence. This was 43% of the global total.

So dollar in a way will continue to be as good as gold. Until it snaps.

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 5, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek and continues to actively bet against the dollar by buying gold through the mutual fund route)