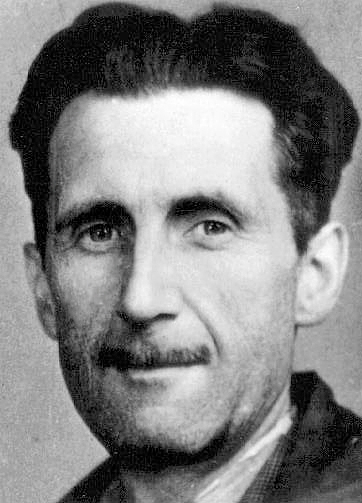

George Orwell towards the end of his brilliant book Animal Farm writes: “There was nothing there now except a single Commandment. It ran: All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.”

Nowhere is this more visible these days than at Indian banks, in particular the government owned public sector banks, and the way they treat their different kind of borrowers. As is well known by now, Indian public sector banks have a massive bad loans problem. This basically means that borrowers who had taken loans over the years are now not repaying them. The bad loans of Indian banks are now among the highest in the world, only second to that of Russia.

The borrowers who have defaulted on their loans primarily consist of large borrowers i.e. corporates, who have taken on loans and are now not repaying them. As per the Economic Survey of 2016-2017, among the large defaulters are 50 companies which owe around Rs 20,000 crore each on an average to the banking system. Among these 50 companies are 10 companies which owe more than Rs 40,000 crore each on an average to the banking system.

These are exceptionally large amounts. Typically, when a borrower defaults the bank comes after him with full force, in order to recover the loan, by selling

assets offered as a collateral against the loan. But this force is not felt by the large corporates. It is felt by the small entrepreneurs who borrow from banks or people like you and me who take on retail loans like home loans, vehicle loans, credit card loans etc.

As former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan said in 2014 speech: “Its full force [i.e., of the banking system] is felt by the small entrepreneur who does not have the wherewithal to hire expensive lawyers or move the courts, even while the influential promoter once again escapes its rigour. The small entrepreneur’s assets are repossessed quickly and sold, extinguishing many a promising business that could do with a little support from bankers.”

Given that they have access to the best lawyers and are close to politicians, the large borrowers don’t feel the heat of the banking system.

In fact, the large borrowers given that they are large, get treated with kids gloves. In some cases, the repayment periods of their loans have been extended. In some other cases, the borrower does not have to pay interest on the loan for a specific period. But all this hasn’t really helped and the banking mess continues.

The Economic Survey of 2016-2017 has recommended based on the data for the year ending September 2016 that “about 33 of the top 100 stressed debtors would need debt reductions of less than 50 percent, 10 would need reductions of 51-75 percent, and no less than 57 would need reductions of 75 percent or more.”

This basically means that banks will have to take on what is technically referred to as a haircut. Let’s say a corporate owes Rs 100 to a bank. A haircut of 51 per cent would mean that he would now owe only Rs 49 to the bank. The bank would have to take on a loss of Rs 51.

The Economic Survey offers multiple reasons why haircuts will be required. The first and the foremost is that the borrowers simply do not have the money to repay. Secondly, large corporates owe money to many banks and these banks need to agree on a strategy to tackle the defaults. That hasn’t happened.

Of course, what the Economic Survey does not tell us is that the large borrowers are politically well connected. It also does not get into the moral hazard haircuts would create. Once corporates are bailed out this time around, why would they go around repaying loans the next time around? They simply won’t have the economic incentive to do so.

And finally, the Survey does not tell us anything about why only the large corporates are being treated with kids gloves? I guess it does not need to because that was something Orwell explained to us many years back.

The column originally appeared in Bangalore Mirror on March 29, 2017.