Vivek Kaul

Saradha chit fund has been in the news lately for all the wrong reasons. But the question that no one seems to be answering is whether Saradha chit fund was really a chit fund? A little bit of digging tells us that Saradha was nowhere near a chit fund. It was nothing but a Ponzi scheme, where money brought in by new investors was used to pay off the old investors. Before we get into the details, lets first try and understand what exactly is a chit fund.

A chit fund is basically a kitty party with a twist.

Yes, you read it right.

The essential part of any kitty party organised by ‘bored’ housewives across India, other than the eating, drinking and gossiping, is the money that is pooled together. So lets say a kitty has twelve women participating in it, with each one of them putting Rs 5,000 per month. The women meet once a month.

When they pool their money together it works out to a total of Rs 60,000 every month. Twelve names are written on chits of paper. From these twelve chits, one chit is drawn. And the woman whose name is on the chit gets the Rs 60,000 that has been pooled together.

When they meet next month eleven names are written on chits of paper and one chit is drawn. The woman who got the money the first time around is left out because she has already got the money once. The woman whose name is on the chit gets the Rs 60,000 that has been pooled together this time around. And so the system works. Every month a chit is drawn and the pooled money is handed over to the woman whose name is on the chit that has been picked.

Of course, the women need to keep paying Rs 5,000 per month, even after they have got Rs 60,000 once. By the time the women meet for the twelfth time everyone who is in on the kitty gets Rs 60,000 once. And that is how a kitty more or less works.

So what is a chit fund?

A chit fund works more or less along similar lines but with a slight twist. Lets assume that the 12 women that we considered earlier come together and decide to contribute Rs 5,000 every month, as they had in the previous case. This means a total of Rs 60,000 will be collected every month. This amount is then auctioned among the 12 members after a minimum discount has been set.

Lets say the minimum discount is set at Rs 5,000. This means the maximum amount any women can get from the total Rs 60,000 collected is Rs 55,000 (Rs 60,000 – Rs 5,000). After this discount bids are invited. All the women bid. One woman bids a discount of Rs 12,000. This is the highest discount that has been bid. And hence, she gets the money.

Since she has agreed on a discount of Rs 12,000, that would mean she would get Rs 48,000 (Rs 60,000 – Rs 12,000). She will also have to bear the organiser charges of around 5% or Rs 3,000 (5% of Rs 60,000). This means she would get Rs 45,000 (Rs 48,000 – Rs 3,000) after deducting the organiser charges.

The discount of Rs 12,000 is basically a profit that the group has made. This is distributed equally among the members, with each one of them getting Rs 1,000. This money that is distributed is referred to as a dividend. Of course the woman who got the money, will have to keep contributing Rs 5,000 every month for the remaining eleven months, like was the case with the kitty.

This is how chit funds works and they are perfectly legal if they are registered under the Chit Funds Act 1982, a central statute or various state-specific acts.

What if two or more women bid the maximum discount?

It is possible that two or more women in the group are equally desperate for the money and bid the highest discount of Rs 12,000. Who gets the money in this case? In this case there names can be written on chits of paper and one chit can be drawn from those chits. The woman whose name is on the chit drawn, gets the money.

Who do chit funds help?

A chit fundhelps those people who are facing a liquidity crunch and by bidding a higher discount amount they can hope to get the money being accumulated. So in the example taken above the woman gets Rs 45,000 by bidding the highest discount amount of Rs 12,000 and paying charges of Rs 3,000. But her contribution to the chit fund has been only Rs 5,000. So by effectively paying Rs 5,000, she has managed to raise Rs 45,000, which she can spend. Of course she will have to keep paying Rs 5,000 for the remaining eleven months. But by doing that the woman gives herself an opportunity to get a bulk amount once.

The chit fund company typically does not ask what the winner of the amount wants to do with the money. As Margadarsi Chit Fund, one of the largest chit funds in the country points out on its website “The purpose of drawing theprized amount need not be disclosed. It can be used for any need by the member for Example: House construction, Marriage, Education, Expansion of business, buy a Computer or any other purpose at his discretion.”

What kind of returns do chit funds give?

As is clear from the above example, chit funds the way they are structured cannot give fixed returns. The kind of return an individual participating in a chit fund gets depends on the maximum discount that is bid in each of the months. The higher the discount, greater is the dividend that is distributed among the members of the chit fund. In the example taken above the maximum discount bid was Rs 12,000. This meant Rs 1,000 dividend could be distributed among the women who were participating in the chit fund. If the maximum discount bid was Rs 6,000, then a dividend of only Rs 500 would have been distributed.

The returns also depend on the organiser charges. At 5%, the organiser of the chit fund in the example taken would get Rs 3,000 every month. At 3% he would have got Rs 1800 every month. Higher organiser charges mean that there is lesser money to distribute and hence lower returns.

While organiser charges are fixed in advance, the maximum winning discounts are likely to vary from month to month, depending the desperation of the individuals bidding. Given this, there is no way a participant in a chit fund can know in advance the kind of returns he can expect. The same stands true for the organiser of the chit fund as well, who cannot know in advance the kind of returns that a participant is likely to get.

Also even at the end of a chit fund, calculating returns is not easy. There are multiple cashflows. In the example taken above, every month there is an outflow of Rs 5,000 for every women who is a part of the chit fund. There is an inflow of dividend every month, which varies from month to month. One month in the year there is an inflow of the bulk amount that the woman wins because she bids the maximum discount in that month. To calculate the exact return, the internal rate of return formula needs to be used. It is difficult to execute this formula manually and needs access to a software like Excel.

Was Saradha a chit fund?

As we just saw a chit fund cannot declare in advance the return an individual is likely to make, given the way its structured. With Saradha chit fund and its promoter Sudipta Sen, that doesn’t seem to have been the case. Returns were promised to prospective investors in advance.

As an article in the Business Standard points out “Sen offered fixed deposits, recurring deposits and monthly income schemes. The returns promised were handsome. In fixed deposits, for instance, Sen promised to multiply the principal 1.5 times in two-and-a-half years, 2.5 times in 5 years and 4 times in 7 years. High-value depositors were told they would get a free trip to “Singapur”.”

If the principal multiplies four times in seven years it means a return of 22% per year. The question is how can such a high rate of return be promised, when bank fixed deposits are giving a return of 8-10% per year? Also, the fact that a rate of return was promised in advance clearly means that what Sen was running was not a chit fund.

This is proven again by a recent order brought out by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) which is against the realty division of Saradha. As the order points out“The average return offered by the noticee (i.e. Saradha)…when the investor opts for returns were between 12% to 24%.” At the cost of repeating, a chit fund the way its structured cannot declare returns in advance.

So what was Saradha then?

The various investment schemes run by the various divisions of the so called Saradha chit fund, which were raising money from investors in West Bengal and other Eastern states, can be categorised under what Sebi calls a collective investment scheme. A collective investment scheme(CIS) is defined as “Any scheme or arrangement made or offered by any company under which the contributions, or payments made by the investors, are pooled and utilised with a view to receive profits, income, produce or property, and is managed on behalf of the investors is a CIS. Investors do not have day to day control over the management and operation of such scheme or arrangement.”

Lets take the case of the realty division of the Saradha chit fund which the Business Standard article referred to earlier says was “the company most active in collecting money from depositors.” Against the money collected Saradha promised allotment of land or a flat. The investors also had the option of getting their principal and the promised interest back at maturity.

The land or the flat was not allotted to investors and the investors did not have day to day control either over the scheme or over the flat or land for that matter. The money/land/flat came to them only at maturity. Given these reasons Saradha was actually a collective investment scheme as defined by Sebi and not a chit fund.

Where did all the money collected go?

This is a tricky question to answer. But some educated guesses can be made. If the Saradha group was collecting money and promising land or flats against that investment, it should still have those assets? Can’t these assets can be sold and some part of the money due to the people of West Bengal be returned? Media reports seem to suggest that all this was simply a sham and there are no real assets. Saradha was trying to create an illusion and was trying to tell its investors and its agents that this is what we are trying to do with the money we are collecting from you. But there was nothing really that it was doing.

The Business Standard quotes a Saradha group agents as follows : “We were bemused to see that only three or four people were working at the site which was being developed as a township. Sen said it would take 20 years to develop the projects as the company had so many businesses and it was not possible for him to oversee all of them,” says Abradeep, a Saradha agent.”

Agents were also frequently taken to Sen’s Global Motors factory which had stopped production in 2011. But when agents came visiting, around 150 people posed as workers in an operational motorcycle factory. If the money being raised from depositors was put to actual use, then flats would have been built and motorcycles made and sold.

All this leads this writer to believe that Saradha and Sen were simply rotating money. They were using money brought in by the newer investors to pay off the older investors whose investments had to be redeemed. At the same time they were creating an illusion of a business as well, which really did not exist.

In the end Sen had to ask his agents to rotate money as well. As the Business Standard points out “Depositors say Sen’s companies were prompt with payments in the first year. Trouble started in January when his employees didn’t get their salaries on time. Then agents were told to make payments for maturities with fresh collections or make adjustment against renewals.” This is what happens in any Ponzi scheme.

So where do chit funds fit into all of this?

Saradha chit fund is not a chit fund. And that seems to be the case with many other so called chit funds in West Bengal. A report in The Asian Age says that there are 73 chit funds running in West Bengal. The question is how many of these funds are genuine chit funds.

What seems to have happened is that a private deposit raising effort from the general public has been labelled as a chit fund. As Vinod Kothari writes in The Hindu “The West Bengal ‘chit funds’ are not chit funds at all, since these have a different structure. Chit funds are mutual credit groups where money circulates among the group members, and the monthly contributions of the chit members are received in rotation by one of the members who bids for it — much like a ‘kitty’…The several names that keep popping up in West Bengal are Collective Investment Schemes or Public Deposit Schemes.”

Most of these collective investment schemes or public deposit schemes do not have any business model in place. They simply rotate money using money brought in by later investors to pay off earlier investors. They also pay high commission to agents to keep bringing new investors. That keeps the Ponzi scheme going.

And as long as money brought in by later investors is greater than the money that has to be paid to earlier investors, these schemes keep running. The day this equation changes, these so called chit funds go bust. The same happened in case of Saradha chit fund as well.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 30, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Month: April 2013

Memo to Sonia: NREGA wasn’t game-changer, growth was

Vivek Kaul

“Perception is reality,” goes the old saying. And the perception among the jhollawallas who belong to the Congress party led United Progressive Alliance (UPA)is that the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) has been a swashbuckling success, which has led to a tremendous increase in rural incomes. So free doles have led to higher income and that in turn has created economic growth, is a conclusion that is often drawn.

A new working paper titled Rising Farm Wages in India – The ‘Pull’ and ‘Push’ Factors written by Ashok Gulati, Surbhi Jain and Nidhi Satija of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP), Ministry of Agriculture, goes a long way in busting this perception.

The real farm wages (i.e. rise in wages adjusted for inflation) grew by 3.7% during the 1990s. The growth fell to 2.1% in 2000s. “So, if real wages had followed the same trend of 1990s in 2000s, the current level of real farm wages would have been higher than what it is today with MGNREGA,” the authors point out.

What is interesting nonetheless is that the data in the 2000s can be divided into two very different parts. Between 2000-01 and 2006-2007, the farm wages declined by 1.8% per year whereas they grew by 6.8% between 2007-2008 and 2011-2012.

On February 2, 2006, MGNREGA was launched in 200 of the most backward districts of the country. The coverage of the scheme was

to all the rural districts from April 1, 2008. The scheme aims at providing at least 100 days of guaranteed employment in a financial year to every household whose adults are willing to do unskilled manual work.

Payments under MGNREGA vary from Rs 120 to Rs 179 per day, depending on the state. “At the national level, with the average nominal wage paid under the scheme increasing from Rs 65 in FY 2006‐07 to Rs 115 in FY 2011‐12… It has set a base price for labour in rural areas, improved the bargaining power of labourers and has led to a widespread increase in the cost of unskilled and temporary labour including agricultural labour,” write the authors of the CACP report.

Guaranteed wages under MGNREGA have increased the wage expectations, although the employment generated under MGNREGA has been less than 10% of the total rural employment in most of the states, during most of the years. And this has led to an increase in farm wages of 6.8% between 2007-2008 and 2011-2012. Or so goes the logic, at least among the jhollawallas.

But causation is not so easy to establish, even though prima facie that might seem to be the case. There are factors other than MGNREGA at work as well. Take the construction sector for example, which competes with agriculture for labour. The share of workforce that is engaged in construction has increased from 3.1% in 1993-94 to 9.6% in 2009-2010. During the same period the share of work force engaged in Indian agriculture declined from 65% to 53%.

As the CACP authors point out “According to 64thround of National Sample Survey (Migration in India), 2007‐08, nearly 57 per cent of urban migrant households migrated from rural areas and mostly for employment related reasons. For rural males, around 20 percent were employed as casual labour after migration…Thus, construction activity certainly competes for rural labour and would act as a pull on farm wages.”

So taking these arguments into account, the CACP authors constructed a statistical model to test what really impacts farm wages. And this throws up some interesting results. A growth of 10% in construction pushes up the farm wages by 2.8%. A 10% increase in overall economic growth (measured through growth in the Gross Domestic Product) pushes up farm wages by 2.4%.

And what about MGNREGA? “Impact of MGNREGA is also significant with 10 percent increase in employment generated leading to around 0.3 – 0.5% increase in farm wages,” write the authors. While, the impact of MGNREGA on farm wages is significant, it is nowhere near the impact that a rise in real economic activity, which is measured through an increase in construction GDP or overall GDP, has had on farm wages. As the authors point out “The impact of growth variables (GDP (overall) or GDP (agri) or GDP(construction)) is almost 4‐6 times higher than the MGNREGA impact.”

The impact that MGNREGA has varies across states. In states like Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal the impact of MGNREGA is better in comparison to other states. But even in this case the impact of real economic activity on farm wages is much greater. Also, the impact that MGNREGA is not significant in states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha, which are among the poorest states in India.

So what is the conclusion that one can draw from this? Simply put, real economic activity has a greater impact on real income than free doles given out by the government. And farm wage would have grown at a much faster rate if the government had taken steps to increase real economic activity.

As the authors point out “These results raise a pertinent policy issue: given fiscal constraints and high food inflation, if there was a trade‐off between allocating resources for welfare schemes and increasing investments with a view to raise farm wages, could the money spent on MGNREGA (more than Rs 2 lakh crore) not be better used if it was for investment in say rural‐urban construction, or for overall growth, or for agrigrowth? These investments would have raised the growth rates in these sectors, and thereby ‘pulled’ the real farm wages through a natural process of development, whereby wages increase broadly in line with rising labour productivity…making the whole process much more economically efficient and sustainable.”

There have been reports of gross irregularities in the NREGA scheme. As the authors write “with the current…Minister of Rural Development himself asking for a CAG probeand the former Minister of Rural Development also alleging lack of effective monitoring. This has serious implications on the overall investment/resource allocation strategy.”

But then who is bothered about leakages and sustainable economic growth. It is all about winning the next Lok Sabha election.

Read the full research paper here

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 29, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

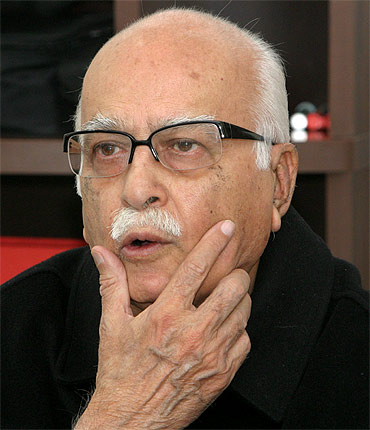

Advani and Modi ties: From guru-shishya to frenemies

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

If media reports are to be believed, Lal Krishna Advani, is looking for a safe seat to contest from, in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. The Gandhinagar Lok Sabha seat in Guajarat from which Advani is currently a member of parliament (MP) is no longer deemed to be safe as it falls in the land of Narendra Modi.

As Coomi Kapoor writes in The Indian Express “Because of the bad vibes between Narendra Modi and Advani on the leadership issue, the latter does not want to put himself at Modi’s mercy by standing again from the Gandhinagar seat.”

Advani it seems has been advised to contest from Lucknow. This would mean latching onto the legacy of Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The other reason here could be the fact that Samajwadi Party chieftain Mulayam Singh Yadav has had nice things to say about Advani in the recent past.

AsIftikhar Gilani writes in the Daily News and Analysis “Advani’s advisors initially wanted him to contest the 2014 election from Lucknow, a seat once represented by former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee. However, with the fast-changing loyalties within the BJP, Modi has laid a claim on both Gandhinagar and Lucknow constituencies to in an attempt to showcase his national acceptance.”

Hence with Modi eyeing to contest from Lucknow as well as Gandhinagar, Advani now plans to contest from a safe seat in Madhya Pradesh. “Advani has reportedly set his sights on the Bhopal constituency since Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan is a friend who can be relied upon. An advance team has already gone to Bhopal to make an assessment of the constituency,” writes Kapoor in The Indian Express. (Another DNA report suggests that Modi wants to contest from Lucknow whereas his trusted lieutenant Amit Shah wants to contest from Gandhinagar).

What is ironical here that it was Modi who first suggested to Advani to contest from Gandhinagar more than two decades back. Advani was looking for a safe Lok Sabha seat to contest from in the 1991 Lok Sabha elections. As Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay writes in Narendra Modi – The Man. The Times “He (i.e. Advani)…relied on Modi to play a crucial role in “giving” him a new political home, Gandhinagar in Gujarat. Advani’s decision to move to Gujarat was because the Congress in 1991 sprang a surprise by nominating the popular film actor, the late Rajesh Khanna, to contest against Advani from New Delhi which had traditionally been a tricky seat owing to comparatively less number of voters (just 4.5 lakh) and a low turnout (in 1991 it was 47.86%). In any case, Advani contested from both New Delhi and Gandhinagar and this proved to be providential as the BJP strongman barely scraped through in the capital by less than 1600 votes.”

Advani has represented Gandhinagar in the Lok Sabha since then, except in the 1996 Lok Sabha elections which he did not contest because he was facing charges of money laundering in the Hawala scam.

A report in The Times of India in 2011 suggested something similar. “In 1991, it was Modi who suggested to Advani that he should contest for Lok Sabha from Gandhinagar…Gandhinagar was until then represented by Modi’s peerturned-foe Shankersinh Vaghela . It was a masterstroke as BJP cadres got charged up in the state and Vaghela was relegated to the fringes . The relationship grew with Advani frequently visiting Gujarat after becoming an MP from the state,” the report pointed out.

The relationship between Advani and Modi did not start in 1991, but a few years before that. Modi was the second pracharak from the Rashtriya Swayemsevak Sangh (RSS) to be deputed to its political affiliate the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP). The first being K N Govindacharya. Those were the days when Modi went around Ahmedabad in an ash coloured Bajaj Chetak scooter.

Modi’s deputation to the BJP took place sometime in 1987-88. This was around the time when Lal Krishna Advani was rebuilding the BJP after the debacle of the 1984 Lok Sabha elections in which the party had won only two seats. Among other things Advani decided to revive the post of organising secretary in the state units of BJP. In the erstwhile Jana Sangh (BJP’s earlier avatar before it merged with other parties to form the Janata Party in 1977) the post was held by RSS pracharaks. Modi was made the organising secretary of the Gujarat unit of the party. “From the beginning it was evident that Modi was Advani’s personal choice and he was keen to strengthen the unit in Gujarat because the state was identified as a potential citadel in the future,” writes Mukhopadhyay.

Modi would soon rise to national prominence when he would play a part in organising Advani’s famed rath yatra which yielded huge political dividends for the BJP. As Mukhopadhyay points out “Modi came into the national spotlight for the first time when he helped organise Advani’s Rath Yatra in September-October 1990…Modi coordinated the arrangements during the Gujarat leg and travelled up to Mumbai and it was a huge success in Gujarat – both in terms of seamless arrangements and public support.”

In the years to come the relationship between Modi and Advani went from strength to strength, with Modi emerging as the super Chief Minister in the BJP government in Gujarat in the mid 1990s. As The Times of India report quoted above points out “It was with Advani’s blessings that Modi emerged as a ‘super CM’ even as he ran the government from the back seat.”

Advani’s fondness for Modi became very well known in the BJP circles. “Throughout the 1990s and even after Modi became chief minister, Advani’s special fondness for Modi has been well known by both party insiders and observers. In 2002, when Modi was under attack for the role of the state administration in Gujarat riots, it was due to Advani’s protection that the BJP leadership gave him a fresh lease of life. Earlier Advani had played a crucial role in the making of Modi as chief minister replacing Keshubhai Patel in October 2001,” writes Mukhopadhyay.

The relationship started to sour after Advani on a visit to Pakistan in June 2005 had good things to say about Mohammed Ali Jinnah. As Advani wrote in the Visitors’ Book at the Jinnah Mausoleum: “There are many people who leave an inerasable stamp on history…But there are very few who actually create history. Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual.”

Advani obviously was trying to get rid of his tag of being the posterboy of Hindutva. But saying nice things about Jinnah went against the entire idea of Akhand Bharat which the RSS believes in. Around this time, Modi started to distance himself from his mentor. Advani had to pay for this statement and had to quit as the BJP party president in late 2005.

And this created space for Modi for a bigger role. As Mukhopadhyay writes “The original poster boy of Hindutva ceased to be and yielded space to the much younger Modi as the mascot of the aggressive Hindu face. At times it appeared that the guru-shishya relationship of yore had been replaced by intense rivalry,” writes Mukhopadhyay.

This rivalry has now come to the fore with Advani looking for a safe seat outside Gujarat to contest from. Modi is trying to inherit the political legacy of both Vajpayee and Advani by wanting to contest the next Lok Sabha elections from both Lucknow as well as Gandhinagar.

The trouble is Advani hasn’t given up as yet his aspirations of becoming the Prime Minister of India. Modi has his supporters within the BJP. As BJP President Rajnath Singh recently told the Open magazine “Narendra Modi is the most popular BJP leader in the country.” But then so does Advani. In an interview to The Economic Times, Yashwant Sinha, a senior BJP leader said “Advaniji is the senior-most, most respected leader and if he is available to lead the party and government, then that should end all discussion. Everyone should fall in line and work together for the party under his leadership. But the call will have to be taken first by Advaniji himself, secondly by the party and finally by NDA (National Democratic Alliance) .” Cine actor Shatrughan Sinha also wants BJP to fight elections under the leadership of Advani.

A factor working in favour of Advani is that he is acceptable to BJP allies like Janata Dal (United). Narendra Modi clearly is not. As the Open Magazine points out “JD-U leader Devesh Chandra Thakur was even more open on the question of Advani’s candidacy for the PM’s post. “The NDA contested under the leadership of LK Advani [in 2009]. I do not think there should be a problem for any NDA faction to go to polls under his leadership. Advani will definitely be more acceptable to most factions of the NDA,” he said after the party’s national executive meeting. “What further indication can Nitish Kumar give?” asks another JD-U leader considered close to the Bihar CM.”

L K Advani, the original posterboy of Hindutva is deemed secular enough to head the NDA. Narendra Modi is not. As Kingshuk Nag writes in The NaMo Story: A Political Life “The ghosts of Gujarat 2002 are likely to haunt Narendra Modi till his last days.”

Advani had to play second fiddle to Vajpayee in the 1990s after building the BJP from scratch. This happened because with Vajpayee at the helm BJP would have been able to attract more allies, which it eventually did. Nearly two decades later Advani might find himself in a similar situation where he(like Vajpayee was) is more acceptable to the potential allies than Narendra Modi is. It is safe to say that no one has served the BJP more than Advani. His contribution to building BJP as a national party is even greater than that of Vajpayee.

Let me conclude this piece with an old bhojpuri saying: “Chela Cheeni Ban Gella, Guru Gud Rah Gella (which loosely translated means the student has become sugar, whereas the teacher continues to be jaggery).” Whether this comes to be true in the context of Advani and Modi, we will find out over the course of the next one year.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 27,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

A case for gold at $10,000 per ounce

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The funny thing is that the more I think I will not write on gold, the more I end up writing on it. So here we go with one more piece analysing the prospects of the yellow metal.

The recent past has seen a host of analysts and economists turn negative on gold. One of the reasons for this has been the feeling that the developed world (US, Europe and Japan i.e.) which had been reeling under the aftermath of the financial crisis since 2008 is now on a roadmap to sustainable recovery.

The irony is that analysts and economists jump at any opportunity to predict a recovery but are nowhere to be seen when a recession is looming. As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writes in a report titled We still forecast 450 S&P, sub-1% US 10year yields, and gold above $10,000 released yesterday “There are some ever-present truths in this business. Economists usually forecast a return to trend growth and will never forecast a recession. Equity strategists tend to forecast the market will rise 10% each year and will never forecast bear markets.”

So dear readers this is an important fact to be kept in mind when reading any dire forecast on gold. As Edwards puts it “The late Margaret Thatcher had a strong view about consensus. She called it: “The process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values, and policies in search of something in which no one believes, but to which no one objects.” The same applies to most market forecasts. With some rare exceptions…analysts dont like to stand out from the crowd.”

And the consensus right now seems to be that gold is done with its upward journey. The logic being offered is that all the money printing that central banks around the world have indulged in since the end of 2008, has helped them repair their respective financial systems and economies. (To know why I don’t believe that is the case click here).

To achieve this economic stability a huge amount of money has been printed. As Gary Dorsch, an investment newsletter writer wrote in a recent column “So far, five central banks, – the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank have effectively created more than $6-trillion of new currency over the past four years, and have flooded the world money markets with excess liquidity. The size of their balance sheets has now reached a combined $9.5-trillion, compared with $3.5-trillion six years ago.”

While this money printing has ‘supposedly’ helped the countries in the developed world move towards economic stability, at the same time it has not led to any inflation, as it was expected to. And this is the main reason being cited by those who have turned bearish on gold.

Gold has always been bought as a hedge against the threat of high inflation. And if there is no inflation why buy gold is the argument being offered.

On the face of it this seems like a fair point to make. But lets try and understand why it doesn’t work. It is important to understand that free money does not and cannot exist. As Dylan Grice of Societe Generale wrote in a report titled The Market for honesty: is $10,000 gold fair value? released in September, 2011 “Since there can be no such thing as a government, or anyone else for that matter, raising revenue ‚at no cost‛ simple logic tells us that someone, somewhere has to pay.”

The point being that when the government finances itself by getting the central bank to print money, someone has to bear the cost.

The question is who is that someone. As Grice wrote “This is where the subtle dishonesty resides, because the answer is that no-one knows. If the money printing creates inflation in the product market, the consumers in that product market will pay. If the money printing creates inflation in asset markets, the purchaser of the more elevated asset price pays. Of course, if the printed money ends up in asset markets even less is known about who ultimately pays for the government’s ‘free lunch’…The ‘free lunch’ providers will be the late entrants into whatever asset-bubble or investment fad the money printing inflates.”

So how does this work in the current context? While the money printing hasn’t led to product inflation in the developed world, the stock markets in the developed world, particularly in the United States and Japan, have been rallying big time. Despite the fact that the respective economies are not in the best of shape. Hence, the money printing even though it hasn’t led to consumer price inflation, it has led to inflation in the stock market. And those investors who will enter these stock markets late, will ultimately bear the cost of all the money printing.

Money that leaves the printing presses of the government need not always end up with people, who use it to buy consumer products and thus push up their price. As Grice puts it “By now, some of you might feel this all to be irrelevant. Surely, you might be thinking, the plain fact is that there is no inflation. I disagree. To see why, think about what inflation is in the light of the above thinking. I know economists define it as changes in the price of a basket of consumer goods, the CPI(consumer price index). But why should that be the definitive measure, given that it’s only one of the many possible destinations in money’s Brownian journey from the printing presses? Why ignore other destinations, such as asset markets? Isn’t asset price inflation (or bubbles as they are more commonly known) more distortionary and economically inefficient than product price inflation?”

The consumer price index which measures inflation is looked at as a definitive measure by economists. But there are problems with the way it is constructed. As a recent report titled Gold Investor: Risk Management and Capital Preservation released by the World Gold Council points out “The weights that different goods and services have in the aforementioned indices do not always correspond to what a household may experience. For example, tuition has been one of the fastest growing expenses for US households but represents only 3% of CPI (consumer price index). In practice, tuition costs correspond to more than 10% of the annual income even for upper-middle American households – and a higher percentage of their consumption.”

This helps in understating the actual inflation number. There are other factors at play as well which work towards understating the actual inflation number. As the World Gold Council report points out “Consumer price baskets are frequently adjusted to incorporate the effect that advancement in technology (e.g. in computer hardware) have on prices paid. These so called hedonic adjustments can overstate reductions in price compared to what consumers pay in practice. For example, a new computer can have the same nominal price as it did five years ago, but adjusting for the processing speed and storage capacity it appears cheaper.”

Then there are also methodological changes that have been made to the consumer price index and the way it measures inflation over the years, which in practice do not always reflect the full erosion of the purchasing power of money.

The following chart shows that if inflation in the United States was still measured as it was in the 1980s would be now close to 10% instead of the official 2%.

The moral of the story is that the situation is not as simple as those who have turned bearish on gold are making it out to be. Given that, how does one view the recent fall in prices of gold on the back of this evidence? As Edwards puts it “Gold corrected 47% from 1974-1976 before rising more than 8x to US$887/oz in 1980. A steep correction is normal before the parabolic move.”

Both Edwards and Grice expect gold to touch $10,000 per ounce (one troy ounce equals 31.1 grams). As I write this gold is currently quoting at $1460 per ounce, having risen from the low of $1350 per ounce that it touched sometime back.

Central banks around the world have tried to create economic growth by printing money. But their efforts to do so are likely to backfire. As Edwards writes “My working experience of the last 30 years has convinced me that policymakers’ efforts to manage the economic cycle have actually made things far more volatile. Their repeated interventions have, much to their surprise, blown up in their faces a few years later. The current round of QE will be no different. We have written previously, quoting Marc Faber, that “The Fed Will Destroy the World” through their money printing. Rapid inflation surely beckons.”

And that’s the point to remember: rapid inflation surely beckons. And to be prepared for that it is important to have investments in gold, the recent negativity around it notwithstanding.

To conclude let me again emphasise that this is how I feel about gold. I may be right. I may be wrong. That only time will tell. So please don’t bet your life on it and limit your exposure to gold to around 10% of your overall investment.

It is important to remember the first few lines of Ruchir Sharma’s Breakout Nations: “The old rule of forecasting was to make as many forecasts as possible and publicise the ones you got right. The new rule is to forecast so far into the future that no one will know you got it wrong.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 26, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek. He has investments in gold through the mutual fund route)

With mai-baap sarkar, 8-9% GDP growth is a pipedream

Vivek Kaul

The economists are at it again. Doing what they are good at i.e. building castles in the air.

The Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (EAC) headed by Dr C Rangarajan released their review of the economy in 2012/13, yesterday. One of the things that the Council points out in this report is “If we (i.e. India) grow at 8 to 9 % per annum, we will graduate to the level of a middle income country by 2025.It is once again a faster rate of growth which will enable us to meet many of our important socio-economic objectives.”

While 8-9% economic growth is a noble thought, what is the chance of it happening given the current state of affairs in the country? The answer is that the situation doesn’t look very good.

The EAC expects an economic growth of 6.4% in 2013-2014 (the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014).

Sustained long term economic growth is very rare. As Ruchir Sharma points out in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “Very few nations achieve long-term rapid growth. My own research shows that over the course of any given decade since 1950, only one-third of emerging markets have been able to grow at an annual rate of 5% or more. Less than one-fourth have kept that pace up for two decades, and one tenth for three decades. Just six countries (Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong) have maintained the rate of growth for four decades, and two (South Korea and Taiwan) have done so for five decades.”

In fact India and China which have been among the fastest growing countries over the last ten years are totally new to this class. “During the 1950s and the 1960s the biggest emerging markets – China and India – were struggling to grow at all. Nations like Iran, Iraq, and Yemen put together long strings of strong growth, but those strings came to a halt with the outbreak of war…In the 1960s, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Burma were billed as the next East Asian tigers, only to see their growth falter badly,” writes Sharma.

The point is that economic growth cannot be taken for granted. There is a lot that can go wrong and it does. In the Indian context that is already coming out to be true. The economic growth rate has fallen from 8-9% to the level of around 5% for the year 2012-2013 (the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31,2013). As the EAC report released yesterday points out “In August 2012, the EAC had projected a likely growth rate for the economy of 6.7 %…At the end of the fiscal year (i.e. as on March 31, 2013)…the actual growth rate at around 5% is much lower than what was projected.”

Different countries have followed different formulas for sustained economic growth at different points of time. But one thing that has almost always killed economic growth is the premature construction of a welfare state, which the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government has at the top of its agenda.

As Sharma writes “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period. Inspired by the popularity of the employment guarantees, the government now plans to spend the same amount extending food subsidies to the poor. If the government continues down this path, India may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

Countries that now run big welfare states have done so after many years of high economic growth. As Gurucharan Das points out in India Grows at Night “India’s leaders did not modernise or expand the capability of its institutions. They forgot that western democracies had taken more than hundred years of economic growth and capacity building to achieve the welfare state.”

While extending subsidies to the poor is a noble idea, the thing is it does not work over a period of time. A recent discussion paper put out by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), Ministry of Agriculture, seems to suggest the same. The paper finds that real farm wages (i.e. growth in wages adjusted for inflation) grew by 3.7% per year in the 1990s. This growth fell to 2.1% per year in 2000s. “The results (of the analysis) points to the fact that a ‘pull strategy’ is more desirable than a ‘push strategy’, meaning growth-oriented investments are likely to be a better bet for raising rural wages and lowering poverty than the welfare-oriented MGNREGS (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme),” the paper pointed out.

The paper also suggests that growth oriented “investments would have raised the growth rates in these sectors, and ‘pulled’ the real farm wages through a natural process of development, whereby wages increase broadly in line with rising labour productivity.” So it is very clear that the governments much touted rural employment guarantee scheme is not really working. The incomes of farmers would have grown much faster had the government simply stayed away.

The other thing all these subsidies (which include oil subsidies which form the bulk of the total subsidies) have done is that it has pushed up government borrowing. “The total public-debt to GDP ratio is now 70% – among the highest for any major developing country,” writes Sharma. “The development of this habit – deficit spending in good times as well as bad – was a major contributor to the current debt problems in the United States and Western Europe, and India can ill afford it.” This is something that the politicians who run India seem to have totally forgotten about.

Increased government borrowing has also led to high interest rates. This has a huge impact on consumption as well as business expansion and in turn pulled down economic growth. The investment by Indian businesses has fallen from 17% of GDP in 2008 to 13% in 2012.

The media has recently been reporting about the finance minister P Chidambaram travelling to different parts of the world soliciting investors to put money in India. And this is happening at a time when more and more Indian companies are setting up businesses abroad. “At a time when India needs its businessmen to reinvest more aggressively at home in order for the country to hit its growth target of 8 to 9 %, they are looking abroad. Overseas operations of Indian companies now account for more than 10% of overall corporate profitability, compared with 2% just five years ago. Given the potential of the Indian domestic market, Indian companies should not need to chase growth abroad,” writes Sharma.

This makes one wonder that if Indian companies are not ready to invest in India, why would foreigners want to do the same? It need not be said that doing business in India has become more and more difficult over the years.

Gurucharan Das in India Grows at Night recounts the experience of a businessman friend of his Navin Parikh. “’Not a week goes by,’ Navin said, ‘without an inspector from some department or the other coming for his hafta vasooli, “weekly bribe”. Labour, excise, fire, police, octroi, sales tax, boilers and more – we have to keep them all happy. Otherwise, they make life hell. More than 10% of my costs are in “managing the system”.”

Given this it is not surprising that more and more Indian businesses are happy going abroad rather than investing in India. And if this continues to happen India’s economic growth will continue to flounder.

The Economic Survey points out that agriculture accounts for 58% of the employment in the country. But this 58% produces only 16% of the country’s GDP. So it is basically a no-brainer to suggest that India needs more industries and businesses, so that people can move out of agriculture. And that cannot happen without the government getting its act right. While a spate of economic reforms, from land to labour, are the need of the hour, but there is something which is more important than even that.

The government of India needs to limit its ambitions. As Sunil Khilnani writes in The idea of India “The state was enlarged, its ambitions inflated, and it was transformed from a distant alien object into one that aspired to infiltrate the everyday life of Indians, proclaiming itself responsible for everything they could desire.”

This anomaly needs to be corrected. The idea of mai-baap sarkar needs to go. Unless that happens, continuous 8-9% economic growth will continue to remain an idea in the heads of economists and politicians.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on April 25, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)