Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

A seemingly popular measure announced in today’s budget is the increase in the tax deduction allowed on home loan interest by Rs 1 lakh. Currently a deduction of Rs 1.5 lakh is allowed to someone buying his first home.

The extra deduction of Rs 1 lakh comes with caveats. The first caveat is that the house should be bought during the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014. The home loan taken should not be more than Rs 25 lakh. And the value of the house being bought should not exceed Rs 40 lakh (something that the finance minister P Chidambaram did not talk about in his budget speech). Chidambaram felt that this move will “promote home ownership and give a fillip to a number of industries like steel, cement, brick, wood, glass etc. besides jobs to thousands of construction workers.”

Let us try and understand why nothing of that sort is going to happen anywhere other than the imagination of Chidambaram. Let us say an individual who falls in the top tax bracket of 30%, takes a home loan of Rs 25 lakh at an interest of 10.5% to be repaid over a period of twenty years. The equated monthly instalment (EMI) to repay this loan would work out to around Rs 24,960. Lets assume this to be Rs 25,000 for the ease of calculation.

What is the extra saving that the individual makes? He gets a tax break of extra Rs 1 lakh. Given that he is in the 30% tax bracket, this means an yearly saving of Rs 30,000 (again lets ignore the 3% education cess for the ease of calculation). This essentially means an added saving of Rs 2,500 per month (Rs 30,000/12).

So what Chidambaram wants us to believe is that people of this country would start paying EMIs of Rs 25,000, in order to make an extra saving of Rs 2,500? No wonder he went to Harvard.

There are other problems with this deduction as well. The deduction is available only for the financial year 2013-2014 (or the assessment year 2014-2015). If the complete deduction is not used in 2013-2014, the remaining part can be used in 2014-2015(or the assessment year 2015-2016). The point is that the deduction is largely available only once. To imagine that people would buy homes to make use of what is essentially a one time deduction is stretching it rather too much. Of course the market understands this. The BSE Realty Index is down around 2.7% from yesterday’s close as I write this.

People don’t buy homes to get a tax deduction. The average middle class Indian buys a home to stay in it. And for that to happen a couple of things need to happen. The real estate prices need to fall from their current atrocious levels. And interest rates also need to fall for EMIs to become affordable.

In fact this is where another comment made by Chidambaram during the course of the speech that makes immense sense. As he said “There are 42,800 persons – let me repeat, only 42,800 persons – who admitted to a taxable income exceeding Rs 1 crore per year.”

This is nothing but a joke. There must be more people earning more than Rs 1 crore in South Delhi, let alone all of India. What this tells us very clearly is that there is a tremendous amount of black money in this country. And all these ill gotten gains are stashed away by buying real estate. This ensures that there are more investors/speculators in the real estate market, than genuine buyers.

Unless this nexus is broken down there is no way anyone who actually needs a house to live in, to be able to actually buy one.

As far as EMIs are concerned they will only come down once interest rates start falling. And for that to happen the government needs to control its borrowing. The borrowing will fall only once the fiscal deficit is under control. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

And I don’t see any of these two things happening in the near future. Neither will black money in the system come down nor will the fiscal deficit fall leading to a fall in interest rates.

Chidambaram ended his speech by quoting his favourite poet Saint Tiruvalluvar. Let me end this piece by quoting one my favourite poets, Bashir Badr.

Musaafir ke raste badalte rahe,

muqaddar mein chalna thaa chalte rahe

Mohabbat adaavat vafaa berukhi,

kiraaye ke ghar the badalate rahe

So the moral of the story is that we will continue to live in rented houses, changing them every 11 months, when the contract runs out.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek)

Month: February 2013

Budget 2013 Analysis: Chidu has just used the bikini formula on you

Vivek Kaul

So let me start this one with a cliché. Statistics are like a bikini. What they reveal is suggestive, but what they conceal is vital. Navjot Singh Sidhu did not say that. Aaron Levenstein, an American professor of business administration did.

The finance minister P Chidambaram, has managed to use the bikini formula on the fiscal deficit number of the budget. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

The fiscal deficit number that Chidambaram and his team have come up with is as Levenstein said is suggestive, but what it conceals is vital. The fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 (the period between 1 April 2012 and March 2013) is likely to stand at Rs 5,20,925 crore or 5.2% of the GDP.

When Pranab Mukherjee had presented the budget last year this number had been projected at Rs 5,13,590 crore or 5.1% of the gross domestic product.

Oil subsidies are an important part of the expenditure of the government. The number at the beginning of the year had been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. The oil marketing companies sell cooking gas, diesel and kerosene at a loss, and are compensated by the government for these losses. This adds to the overall expenditure of the government and thus to the fiscal deficit.

So what is interesting is that in the budget presented today the oil subsidy number has been revised to Rs 96, 880 crore. This more than double the number that had been assumed at the beginning of the year. But this does not take into account the total losses or under-recoveries incurred by the oil marketing companies.

As Chapter 3 of the Economic Survey released yesterday points out “The Indian basket crude oil was $107.52 per bbl (April-December) in 2012 and even with the pass through effected in the course of the year, under-recoveries of OMCs surged and were estimated at Rs1,24,854 crore during April-December 2012-13.”

So the under-recoveries on account of selling cooking gas, diesel and kerosene at a loss stood at Rs 1,24,854 crore for the first nine months of the financial year. If we do a simple mathematical projection this number for the financial year 2012-2013 should be Rs 1,66,107.7 crore ((12/9) x Rs 1,24,854 crore).

While this may be a slightly simplistic way to operate but what it reveals is vital. Also let me make another assumption to make this calculation a little more robust. Since January the oil marketing companies have been allowed to raise prices of diesel on a slow but regular basis. The number of cooking gas cylinders that can be taken in a given year at a subsidised rate has also been limited to nine. So lets further assume that all this helps and the under-recoveries of oil marketing companies for the financial year 2012-2013 will turn up around Rs 1,55,000 crore.

The oil subsidies when the last budget was presented had been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. The budget presented today has revised this number to Rs 96,880 crore. But even that is not enough to make do for the losses that have been incurred by the oil marketing companies and who need to be compensated for the by the government.

So there is a gap of around Rs 60,000 crore. The question here is that how will oil marketing companies be compensated for their under-recoveries if no provision is made for it in the budget? The simple answer is that they will be compensated for the under-recoveries from the next year’s budget i.e. the budget for the financial year 2013-2014 (the period between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014). Or the finance minister will get companies like ONGC and Oil India Ltd, which produce oil to pay for the difference.

Now how do the oil subsidies for next year look? The oil subsidies for the year 2013-2014 have been assumed to be at Rs 65,000 crore. It need not be said that oil marketing companies will face under-recoveries in the next financial year. These under-recoveries might be lower given that diesel prices are being gradually raised and all cooking gas is no longer subsidised. But there will be under-recoveries none the less. Given that the under-recoveries this year were at Rs 1,50,000 crore, even with higher diesel prices and limited subsidised cooking gas cylinders, the oil subsidy number is likely to be more than Rs 65,000 crore.

Hence, the fiscal deficit for the next financial year has also been understated to that extent. While some sort of accounting jugglery is expected in the budget this is getting a rather too blatant. ONCG and Oil India Ltd will have to come to the rescue of the oil marketing companies and the government again. It need not be said that this is not prudent accounting at all.

What is interesting is that this is a tactic that the Congress led United Progressive Alliance has constantly adopted (as can be seen from the accompanying tables). The budgeted subsidies are substantially lesser than the actual number. This tends to underdeclare fiscal deficit at the beginning of the year.

Other subsidies on fertilizer and food have also been regularly underestimated by a large amount as can be seen from the following tables.

What these tables clearly tell us is that subsidies are underestimated almost every year and sometimes by huge margins. For the year 2012-2013 subsidies were expected to be at Rs 190015.13 crore. The revised estimate has come in at Rs 257654.43 crore, which is almost 36% higher. This makes it very difficult to believe the next year’s subsidy target of Rs 231083.52 crore especially when more subsidies/sops are likely to be announced during the course of the next financial year in lieu of the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. If the government does meet this target then it will have to cut on other planned spending, like it has done this year. And that can’t be good for the Indian economy.

Given this the fiscal deficit target of 4.8% of GDP or Rs 5,42,499 crore, for the next financial year is unlikely to be met.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 28,2013

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek

Subsidies = Inflation = Gold problem

The government has a certain theory on gold as per which buying gold is harmful for the Indian economy. Allow me to elaborate starting with something that P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, recently said “I…appeal to the people to moderate the demand for gold.”

India produces very little of the gold it consumes and hence imports almost all of it. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. When someone from India buys gold internationally, Indian rupees are sold and dollars are bought. These dollars are then used to buy gold.

So buying gold pushes up demand for dollars. This leads to the dollar appreciating or the rupee depreciating. A depreciating rupee makes India’s other imports, including our biggest import i.e. oil, more expensive.

This pushes up the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) as well as our fiscal deficit (the difference between what the government earns and what it spends).

The fiscal deficit goes up because as the rupee depreciates the oil marketing companies(OMCs) pay more for the oil that they buy internationally. This increase is not totally passed onto the Indian consumer. The government in turn compensates the OMCs for selling kerosene, cooking gas and diesel, at a loss. Hence, the expenditure of the government goes up and so does the fiscal deficit. A higher fiscal deficit means greater borrowing by the government, which crowds out private sector borrowing and pushes up interest rates. Higher interest rates in turn slow down the economy.

This is the government’s theory on gold and has been used to in the recent past to hike the import duty on gold to 6%. But what the theory doesn’t tells us is why do Indians buy gold in the first place? The most common answer is that Indians buy gold because we are fascinated by it. But that is really insulting our native wisdom.

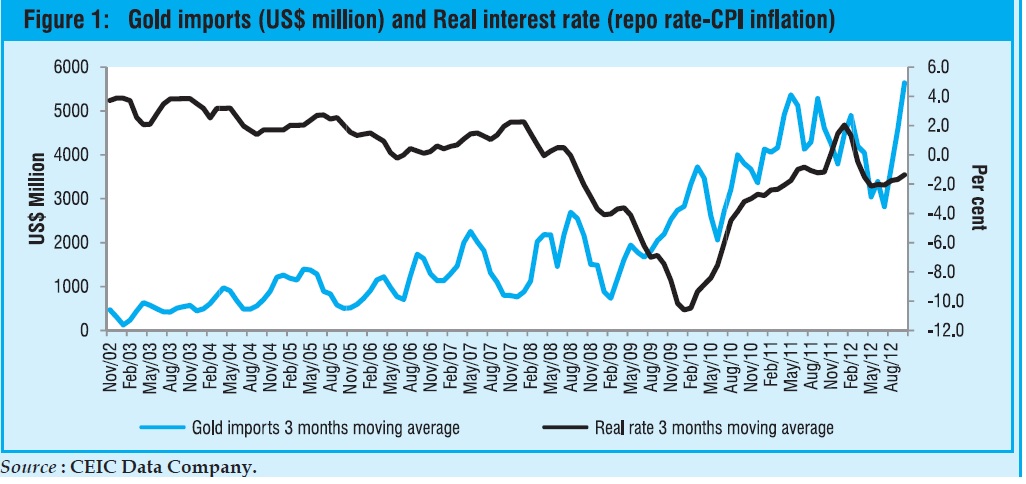

World over gold is bought as a hedge against inflation. This is something that the latest economic survey authored under aegis of Raghuram Rajan, the Chief Economic Advisor to the government, recognises. So when inflation is high, the real returns on fixed income investments like fixed deposits and banks is low. As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.”(as can be seen from the accompanying table at the start)

In simple English, people buy gold when inflation is high and the real return from fixed income investments is low. That has precisely what has happened in India over the last few years. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Survey points out.

High inflation in India has been the creation of all the subsidies that have been doled out by the UPA government. As the Economic Survey puts it “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

Inflation thus is a creation of all the subsidies being doled out, says the Economic Survey. And to stop Indians from buying gold, inflation needs to be controlled. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance,” the Survey points out. So if Indians are buying gold despite its high price and imposition of import duty, they are not be blamed.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

It is Sonia who needs to read Rajan’s Economic Survey

Vivek Kaul

Raghuram Govind Rajan, the chief economic advisor to the government of India, likes to talk straight and call a spade a spade. He was the first economist of some standing to take on Alan Greenspan’s economic policies at a public forum. In a conference in 2005, Rajan said “The bottom line is that banks are certainly not any less risky than the past despite their better capitalization, and may well be riskier. Moreover, banks now bear only the tip of the iceberg of financial sector risks…the interbank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis.”

This was during the time when the United States of America was in the middle of a real estate bubble. Everyone was having a good time. And no one wanted to spoil the party.

Alan Greenspan hadn’t achieved the ignominy that he now has, and was revered as god, at least in economic circles. Hence, any criticism of the American economy was seen as criticism of Greenspan himself. Given this, Rajan came in for heavy criticism for what he said. But we all know who turned out to be right in the end.

Recalling the occasion Rajan later wrote in his book Fault Lines “I exaggerate only a bit when I say I felt like an early Christian who had wandered into a convention of half-starved lions. As I walked away from the podium after being roundly criticised by a number of luminaries (with a few notable exceptions), I felt some unease. It was not caused by the criticism itself…Rather it was because the critics seemed to be ignoring what going on before their eyes.”

What this tells us is that Rajan doesn’t hesitate in pointing out what is going on before his eyes, even though it might be politically incorrect to do so. This clearly comes out in the Economic Survey for the year 2012-2013. A part of the summary to the first chapter State of the Economy and Prospects reads “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

The last sentence of the above paragraph makes for a very interesting reading. This is probably the first occasion where a government functionary has conceded that it is the increased government spending during the second term of the UPA that has led to a high inflationary scenario. This is not surprising given that Rajan holds a full time job teaching at the University of Chicago.

Rajan’s thinking is in line with what the late Milton Friedman, a doyen of the University of Chicago, had been talking about since the early 1960s. As Friedman writes in Money Mischief – Episodes in Monetary History: “The recognition that substantial inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon is only the beginning of an understanding of the cause and cure of inflation…Inflation occurs when the quantity of money rises appreciably more rapidly than output, and the more rapid the rise in the quantity of money per unit of output, the greater the rate of inflation. There is probably no other proposition in economics that is as well established as this one.”

And that is what has happened in India with the government spending more and more money over the last five years. This money has chased the same number of goods and services and thus led to higher prices i.e. inflation.

Rajan has never been a great fan of subsidies and he looks at them as a short term necessity. In an interview I did with him after the release of his book Fault Lines, for the Daily News and Analysis(DNA), I had asked him whether India could afford to be a welfare state, to which he had replied “Not at the level that politicians want it to.”

In another interview that I had done with him in late 2008, for the same newspaper, he had said “There is a real concern in India that government in India is not doing enough of what it should be doing…I don’t agree that we should overspend and run large deficits but I think we should bite the bullet and cut back on subsidies where we can for the larger good of the public investment into agriculture, roads etc.”

This kind of thinking that Rajan is known for clearly comes out in the Economic Survey. The subsidy bill (oil, food and fertilizer primarily) for the current financial year 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013) is estimated to be at Rs 1,90,015 crore. This has to come down. As the Economic Survey points out “Controlling the expenditure on subsidies will be crucial. Domestic prices of petroleum products, particularly diesel and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) need to be raised in line with the prices prevailing in international markets. A beginning has already been made with the decision in September 2012 to raise the price of diesel and again in January 2013 to allow oil marketing companies to increase prices in small increments at regular intervals.”

The question is that will this be enough. The amount budgeted for oil subsidies during the course of this financial year was Rs 43,580 crore. These subsidies are given to oil marketing companies because they sell diesel, cooking gas and kerosene at a loss.

The amount budgeted against oil subsidies will not be enough to meet the actual losses. As the Chapter 3 of the Economic Survey points out “The Indian basket crude oil was $107.52 per bbl (April-December) in 2012 and even with the pass through effected in the course of the year, under-recoveries of OMCs surged and were estimated at Rs1,24,854 crore during April-December 2012-13.”

So for the first nine months of the year the oil subsidy bill was more than Rs 81,000 crore off the target. By the end of the financial year this might well touch Rs 1,00,000 crore. This of course will need some clever accounting to hide. Chances are that the finance minister P Chidambaram might move this payment that will have to be made to the oil marketing companies to the next financial year.

Hence it becomes even more important to cut these subsidies in the years to come. As Rajan writes “The crucial lesson that emerges from the fiscal outcome in 2011-12 and 2012-13 is that in times of heightened uncertainties, there is need for continued risk assessment through close monitoring and for taking appropriate measures for achieving better fiscal marksmanship. Openended commitments such as uncapped subsidies are particularly problematic for fiscal credibility because they expose fiscal marksmanship to the vagaries of prices.”

The phrase to mark over here is that ‘open ended commitments such as uncapped subsidies are particularly problematic‘. This is something that Sonia Gandhi, president of the Congress party, and Chairman of UPA wouldn’t want to hear. This specially during a time when Lok Sabha elections are due in a little over a year’s time and this budget is the last occasion which the government can use to continue bribing the Indian public through subsidies.

It will be interesting to see whether the finance minister P Chidambaram takes any of the suggestions put forward by Rajan and his team, when he presents the annual budget tomorrow. Or will this Economic Survey, like many before it, be also confined to the dustbins of history?

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 27, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek )

Hari Narayan ran Irda like an insurance lobby

Vivek Kaul

What is it with outgoing Indian bureaucrats and their tendency to become remarkably honest about all that is wrong with the Indian system, once they retire?

The latest to join this long list is Jandhyala Hari Narayan, the recently retired chief of the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority(IRDA) of India, the insurance regulator. In an interview to the Mint newspaper, a few days back, Hari Narayan said “I think there is a philosophical problem.I think the regulators are probably closer to the industry than they ought to be.”

While I don’t know whether its a philosophical problem, it definitely is a problem. Much through Hari Narayan’s stint at IRDA, the regulator acted more like an industry lobby, rather than an institution which was also supposed to protect the interests of those buying insurance policies.

Allow me to elaborate.

During Hari Narayan’s reign IRDA put out advertisements urging people to buy unit linked insurance plans (Ulips). Ulips are essentially investment plans carrying a dash of insurance. Ulips used to pay very high commissions to insurance agents, which has since fallen. So to put it in another way, they are high cost mutual funds, which also provide you with some insurance.

Now which regulator puts out advertisements asking people to buy the product that it regulates? This would be like the Securities and Exchange Board of India(Sebi) putting out advertisements asking people to buy mutual funds. Or the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, the telecom regulator, putting out advertisements, asking people to buy mobile phone connections.

And if that wasn’t enough, Hari Narayan also cleared highest NAV guaranteed plans without understanding the damage they would cause to those investing. These plans were typically 10 year plans. Some of these plans guaranteed the investor the highest NAV achieved during the first seven years of the plan. Some others guaranteed the highest NAV achieved during the entire duration of the plan.

What is ironic is that these investment plans had the flexibility to invest up to 100% of the money they collected in the stock market. And how can the stock market and any guarantee go together? Those who still believe in this need to be reminded of this institution called Unit Trust of India (UTI), which tried to provide investors with assured returns by investing in the stock market and failed spectacularly.

Hari Narayan conveniently blamed the clearing of this product on the actuary at IRDA at that point of time. “I think there was a process of understanding even at Irda and I don’t think the then member actuary was really so clearly focused on policyholders’ welfare as he ought to have been. So it took some time to really figure it out,” he told Mint. Why clear a product which you don’t understand? I am amazed that this is how decision making happens at one of India’s foremost regulators.

What is interesting is the way these plans were sold by insurance companies. These plans were made to look like 100% stock market products. They gave an impression that the money collected would be invested in the stock market and the money would continue to remain invested in the stock market. And the highest NAV that the plan achieved during the course of its tenure would be paid out in the end, irrespective of the prevailing NAV.

Let me explain through an example. Let us say initially the NAV is Rs 10. The money collected is invested in the stock market. The value of these investments rises by 50% and the NAV increases to Rs 15 (Rs 10 + 50% of Rs 10). After this the stock market starts to fall and by the time the policy matures the NAV has fallen to Rs 12. So as per the terms of the policy the highest NAV of Rs 15 would be paid out to the policy holders.

This of course meant that the insurance company would have to pay out Rs 3 from its own pockets. Now it need not be said that insurance companies are in the business of making profits and not losses. So the way these plans were really structured was different. In all likelihood these plans would have a higher exposure to equity initially and gradually move the investments into debt as the date of maturity neared. Also, gains made on investing in stocks would be regularly booked and moved to debt, so as to ensure that the NAV did not rise beyond a certain level. But this is not how the product was sold.

This was misselling at its best. And this was not the only form of misselling that happened. There were other standard techniques of misselling. Investors were promised that there investment would double in three years. There was also a lot of churning. Investors were made to stop their investment in Ulips after three years and the new premium was directed into newer Ulips. This was done because Ulips paid higher commissions during the first two years. Irda turned a blind eye to all this.

And the results of all this misselling are now coming out. Those who invested in Ulips are now finding out a few years later, that instead of their investments doubling, they are still losing money on it. This is primarily because a lot of money they invested went to pay commission to insurance agents. In fact payments made to insurance agents have been more than what the Insurance Act permits. “These payment are more than what the (Insurance )Act permits,” Hari Narayan told Mint.

The losses have led to more people surrendering their insurance policies before they matured. As a recent report in The Hindu Business Line points out “According to IRDA (Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority) data, in fiscal 2012 life insurers had to pay Rs 71,208 crore on account of surrenders (withdrawals), of which, LIC paid Rs 41,531 crore and private sector insurers, the balance. In fiscal 2012, ULIPs accounted for 68 per cent of the total surrender for LIC, and 97 per cent of the total for private insurers.”

So between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012, policy holders surrendered insurance policies worth around Rs 71,000 crore. And a major portion of this was Ulips.

An earlier report in the Mint points out that investors may have lost more than Rs 1,56,000 crore in the seven period ending on March 31, 2012, due to misselling by insurance companies. And that is clearly a lot of money. Hari Narayan was in-charge of IRDA during much of this period. What these losses also do is that they make the so called small or retail investor wary of anything to do with the stock market. And that is not a good sign in a developing economy like India which needs a lot of money to keep growing.

To give Hari Narayan due credit during the second half of his tenure he did try and set things right by cutting down Ulip commissions and also tried to do a thing or two about misselling. But by then the damage had already been done. It was a case of too little too late. The insurance companies simply moved towards selling traditional insurance policies, where the commissions continue to remain high. The guaranteed NAV plans continue to be sold.

Also, the bigger problem with Ulips remain. An investor still cannot figure out which is the best Ulip going around given that returns across different Ulips remain incomparable.

Hari Narayan has been replaced by T S Vijayan, a former Chairman of Life Insurance Corporation of India. Predictably the insurance companies have upped the rhetoric with one of their own taking over as the regulator. As a recent story in the Business Standard pointed out that insurers felt that there was no need to ban highest NAV guaranteed products. The story quoted a chief executive of a private life insurance company as saying “The products, per se, do not have any fundamental problem. The problem is it these have a tendency to be mis-sold, since the customer does not understand market fluctuations could be risky. Hence, disclosures should be made clearer, rather than banning the product.” As the American writer Upton Sinclair once wrote “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

Given this, I expect the misselling in insurance to continue.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 26, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek)