Vivek Kaul

Abhijit V Banerjee and Esther Duflo in their book Poor Economics – Rethinking Poverty & the Ways to End It write a very interesting story about a woman they met in the slums of Hyderabad. This woman had borrowed Rs 10,000 from Spandana, a microfinance institution.

As they write “A woman we met in a slum in Hyderabad told us that she had borrowed 10,000 rupees from Spandana and immediately deposited the proceeds of the loan in a savings bank account. Thus, she was paying a 24 percent annual interest rate to Spandana, while earning about 4 percent on her savings account”.

The question of course was why would anyone in their right mind do something like this? Borrow at 24% and invest at 4%? But as the authors found out there was a clear method in the woman’s madness. “When we asked her why this made sense, she explained that her daughter, now sixteen, would need to get married in about two years. That 10,000 rupees was the beginning of her dowry. When we asked why she had not opted to simply put the money she was paying to Spandana for the loan into her savings bank account directly every week, she explained that it was simply not possible: other things would keep coming up…The point as we eventually figured out, is that the obligation to pay what you owe to Spandana – which is well enforced – imposes a discipline that the borrowers might not manage on their own.”

The example brings out a basic point that those with low income find it very difficult to save money and in some cases they even go to the extent of taking a loan and repaying it, rather than saving regularly to build a corpus.

This includes a lot of very small entrepreneurs and people who do odd jobs and make money on a daily basis. Such individuals have to meet their expenses on a daily basis and that leaves very little money to save at the end of the day. Also the chances of the little money they save, being spent are very high. As Abhijit Banerjee told me in an interview I did for the Economic Times “The broader issue is that savings is a huge problem. Cash doesn’t stay. Money in the pillow doesn’t work.”

Hence, as the above example showed it is easier for people to build a savings nest by borrowing and then repaying that loan, rather than by saving regularly.

Another way building a savings nest is by visiting a bank regularly and depositing that money almost on a daily basis. But that is easier said than done. In a number of cases, the small entrepreneur or the person doing odd jobs, figures out what he has made for the day, only by late evening. By the time the banks have closed for the day.

The money saved can easily be spent between the evening and the next morning when the banks open. Also, in the morning the person will have to get back to whatever he does, and may not find time to visit the bank. Banks also do not encourage people depositing small amounts on a daily basis. It pushes up their cost of transacting business.

But what if the bank or a financial institution comes to the person everyday late in the evening, once he is done with his business for the day and knows exactly what he has saved for the day. It also does not throw tantrums about taking on very low amounts.

This is precisely what Subrata Roy’s Sahara group has been doing for years, through its parabankers who number anywhere from six lakh to a million. They go and collect money from homes or work places of people almost on a daily basis.

The Sahara group fulfilled this basic financial need of having to save on a daily basis for those at the bottom of the pyramid (as the management guru CK Prahalad called them). The trouble of course was that there was very little transparency in where this money went. The group has had multiple interests ranging from real estate, films, television, and now even retail. A lot of these businesses are supposedly not doing well.

Over the last few years, both the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and Securities and Exchange Board of India(Sebi), have cracked down on the money raising schemes of the Sahara group. In a decision today, the Supreme Court of India has directed that the Sahara group refund more around Rs 17,700 crore that it raised through its two unlisted companies between 2008 and 2011. The money was raised from 2.2crore small investors through an instrument known as fully convertible debenture. The money has to be returned in three months.

Sebi had ordered Sahara last year to refund this money with 15% interest. This was because the fund-raising process did not comply with the Sebi rules. Sahara had challenged this, but the Supreme Court upheld Sebi’

The question that arises here is that why has Sahara managed to raise money running into thousands of crores over the last few decades? The answer probably lies in our underdeveloped banking system. In a November 2011 presentation made by the India Brand Equity Foundation ( a trust established by the Ministry of Commerce with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) as its associate) throws up some very interesting facts. A few of them are listed below:

– Despite healthy growth over the past few years, the Indian banking sector is relatively underpenetrated.

– Limited banking penetration in India is also evident from low branch per 100,000 adults ratio – – Branch per 100,000 adults ratio in India stands at 747 compared to 1,065 for Brazil and 2,063 for Malaysia

– Of the 600,000 village habitations in India only 5 per cent have a commercial bank branch

– Only 40 per cent of the adult population has bank accounts

What these facts tell us very clearly is that even if a person wants to save it is not very easy for him to save because chances are he does not have a bank account or there is no bank in the vicinity. This is where Sahara comes in. The parabanker comes to the individual on a regular basis and collects his money.

As a Reuters story on Sahara points out “Investors in Sahara’s financial products tend to be from small towns and rural areas where banking penetration is low. “They see Sahara on television everyday as sponsor of the cricket team and that leads them to believe that this is the best company,” said a spokesman for the Investors and Consumers Guidance Cell, a consumer activist group.”

Sahara has built trust over the years by being a highly visible brand. It sponsors the Indian cricket and hockey team. It has television channels and a newspaper as well. Hence people feel safe handing over their money to Sahara.

The irony of this of course is that RBI which has been trying to shut down the money raising activities of Sahara is in a way responsible for its rise, given the low level of banking penetration in the country.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 31,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/why-the-poor-are-willing-to-hand-over-their-money-to-sahara-438276.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Month: August 2012

Ta-ta: How Ratan rebuilt the house that JRD left him

Vivek Kaul

Among the many tourist attractions of Mumbai are homes of famous people. The Ambanis used to live in Sea Wind building at Cuffe Parade till Mukesh Ambani built the 27-floor Antilia on Altamont Road. Kumar Mangalam Birla’s bungalow is very close to Mukesh’s Antilia. So is the Jindal Mansion of the Jindal family.

Lata Mangeshkar’s flat in Prabhu Kunj building is not too far off. Recent news reports suggest that industrialist Gautam Singhania is building a 40- storeyed building, JK House ,on Warden Road, which again is in the vicinity of Ambani’s Antilia.

For those who are historically inclined, there is Jinnah House (originally referred to as South Court), the erstwhile residence of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, which is very close to the residence of the Chief Minister of Maharashtra.

The other famous residences in the city are Amitabh Bachchan’s Jalsa and Pratiksha, Shahrukh Khan’s Mannat, the late Rajesh Khanna’s Aashirwad and Salman Khan’s one-bedroom-hall-kitchen flat in Galaxy Apartments.

Before you start wondering why I am giving you all these titbits that you may already be aware of, let me tell you, dear reader, that I have always wondered where Ratan Tata lives.

Where is his Anitilia and his Jalsa? Is it as posh as the other residences I have mentioned above? And given the fact that Tata is an architect by qualification, did he design it himself?

The point is that unlike a lot of other industrialists, Tata is very low key. You won’t find him hosting a Page 3 party or even attending one for that matter. His reclusiveness is famous. No wonder The Economist magazine, in a January 2007 profile of him, called him the “shy” architect.

But, as it turns out, he has designed only two houses till date. As the Guardian newspaper wrote in a 2008 profile of his “He only designed two houses: his mother’s and his own beach-house off the Arabian sea.” (You can read the complete profile here)

Ratan Tata took over as Chairman of Tata Sons in 1991, just as the Indian economy was opening up. “His uncle (JRD Tata), who had run Tata for more than 50 years, had started Tata Airlines (which became Air India)…He was a good-looking philanthropist with a French wife and held the first pilot’s licence to be issued in India.His shy and unglamorous nephew, in contrast, trained as an architect at Cornell University, slipped quietly into the family firm and was not marked out for the succession even when his uncle was due to bow out,” wrote The Economist in the 2007 profile. (You can read the complete profile here)

Ratan Tata took over as Chairman of the group from the great Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, or JRD Tata, of Jeh as he was known to friends. JRD had been Chairman of the group for more than 50 years starting in 1938. He took over the reins after the untimely death of Sir Nowroji Saklatvala.

JRD Tata’s father RD Tata was the first cousin of Jamsetji Tata, the founder of the Tata group, and had been a partner in the original Tata & Sons. As Morgen Witzel writes in Tata —The Evolution of a Corporate Brand: “He (RD Tata) had been a partner in the original Tata & Sons, but then moved to Paris, where he set up in business on his own account…He married a Frenchwoman (Suzanne Briere), and JRD their eldest son was born in 1904…He grew up and was educated in France; years later, some Indians remarked that he still spoke with a French accent.”

JRD was surprised at being appointed Chairman of Tata Sons and, as Witzel points out, he “once described the decision of the directors to appoint him as chairman as a ‘moment of mental aberration’”. But the group did rather well under him despite the setbacks it received in the way of its companies being nationalised by the government now and then. In 1939, the group had 14 companies with total sales of Rs 280 crore. By the time JRD retired and Ratan took over, the group had more than 50 companies with sales of around Rs 15,000crore.

JRD was a visionary and a lot of labour reforms that Indian corporates had to carry out over the years where envisaged by him and first implemented within the Tata group. “Tisco (Tata Iron & Steel Co, now Tata Steel) was…probably the first company in India to have a dedicated human resources department, a practice followed by other Tata companies,” writes Witzel.

JRD was also a great believer in letting his managers do what they wanted to do. This was one of the reasons why the Tata group reached the size that it did under JRD. “Russi Mody…was exceptional in the way he steered Tata Steel through difficult times; Darbari Seth built Tata Chemicals and Tata Tea from scratch; Ajit Kerkar was instrumental in turning a one-hotel company into a 1,000-room hospitality giant. And, of course, there was the indomitable Nani Palkhivala, who served on the board of many Tata group companies,” an Outlook Business story on the Tata group points out. (You can read the complete story here)

But what this freedom did was that it made the entire group very unwieldy. “JRD had a clean, uncomplicated portfolio of businesses when he took over in 1938. There was textiles, the group’s first business, steel, power, cement, insurance, and, of course, JRD’s first love—aviation… In 1991, the Tata business structure was quite complicated. Till then, the group was not run as one business group.

Each company was led in the direction that each of the mercurial chairmen chose. JRD allowed them to give full vent to their managerial entrepreneurialism. The result was a maze of businesses. Three companies were making cement and at least five were in the pharmaceutical business in some form or the other,” points out Outlook Business. Other than making the group unwieldy different managers ran different companies within the group as their own personal fiefdoms.

What also did not help was the fact that JRD did not bother much about ownership. As Witzel points out, “By the 1980s Tata Sons held a smaller share of steel-maker Tisco than did their rivals the Birlas. Tata Sons’ share of…truck maker Tata Engineering & Locomotive Co (Telco, now Tata Motors) had declined to 3 percent, and its share of Indian Hotels, the parent company for many of the Taj Hotels, was now just 12 percent…The family’s own stake in Tata Sons had shrunk to just 1.5 percent,while construction magnate Pallonji Mistry owned 17.5 percent… ‘There was a question,’ says Ratan Tata, ‘as to whether we had the right to claim to manage these companies. In fact we didn’t have the legal right or even the moral right, to manage them.’”

What also did not help was the fact that JRD had left the appointment of Ratan as Chairman till very late in the day. Speculation had been rife on who would succeed JRD since the mid-1980s, when JRD had crossed the age of 80. JRD it is said to have made up his mind to pass on the baton either to Russi Mody or Nani Palkhivala.

Palkivala’s political views worked against him. And Russi Mody did not do his chances much good by criticising the performance of other senior leaders within the group. So it was left to JRD to pass on the baton to another Tata.

Ratan Tata was born to Naval and Soonoo Commisariat in 1937. Ratan’s father Naval Tata was the adopted son of Lady Navajbai, who was the wife of Sir Ratan Tata, one of the sons of the group founder Jamsetji Tata. Sir Ratan Tata died of a heart attack at the age of 47 in 1918. He and Lady Navajbai did not have any children. Neither did his elder brother Sir Dorabji Tata.

So it was decided that Lady Navajbai would adopt Naval, who was an orphan and the son of Sir Ratan’s favourite cousin.

As business historian Gita Piramal told the Guardian newspaper a few years back: “The Tatas are a reconstructed family who adopt and cobble together people to make a family. That way they do promote talent rather than blood relations.”

Ratan Tata completed his graduation in architecture from Cornell University in the United States in 1962. It is said that he had a job offer from IBM but he came back to India and was put to work at Tisco, what was then the biggest group company.

His first independent assignment was in 1971 as the director of National Radio and Electronics (Nelco) which was in dire straits. As soon as Tata had managed to turn the company around, Indira Gandhi declared emergency and Nelco was in dire straits again.

Tata was then asked to turn around Empress Mill, which was one of the three businesses started by the group founder Jamsetji Tata (the other two being the Taj Mahal hotel and Tata Steel)). Tata managed to turn around the sick mill but was refused an investment of Rs 50 lakh that was needed. Soon the mill workers’ strike led by Datta Samant hit Bombay (now Mumbai), and the mill had to be shut down in 1986.

In 1981, Ratan Tata was appointed as the Chairman of Tata Industries. “Ratan helped draw up a group strategic plan in 1983. Among other things, it emphasised venturing into hi-tech businesses; focusing on select markets and products; judicious mergers and acquisitions; and leveraging group synergies.

Accordingly, Ratan promoted seven hi-tech businesses under Tata Industries in the eighties: Tata Telecom, Tata Finance, Tata Keltron, Hitech Drilling Services, Tata Honeywell, Tata Elxsi and Plantek,” points out another Outlook Business story on the Tatas. (You can read the complete story here).

But outside Tata Industries, the blueprint did not achieve any success with various CEOs and managing directors continuing to run their individual fiefdoms. Given this, Ratan Tata’s career within the Tata Group hadn’t been great shakes and his appointment as Chairman was as big a surprise for others as it was for himself. This is something that Ratan Tata admitted to in an interview later. He had believed that Palkhivala and Mody were the main players in the race.

So it remains a mystery as to why Ratan Tata was appointed as the Chairman of Tata Sons by JRD. One version is pointed out by Tata group historian RM Lala in an interview to Outlook Business.

“RM Lala recalls speaking with JRD some 10 days after the announcement and asking whether Ratan had been chosen because of his integrity. ‘Oh no, I wouldn’t say that; that would mean the others did not have integrity,’ JRD replied. ‘I chose him because of his memory. Ratan will be more like me.’” Was this JRD’s way of saying that Ratan Tata was chosen because he was a Tata at the end of the day? He probably felt that only someone with the Tata name could hold a group built by various satraps independently together. But we will never know for sure.

The first few years of Ratan’s tenure as the Chairperson were spent fighting the leaders within the Tata group and the fiefdoms they had built. And the fight with Russi Mody got very ugly with JRD having to fire Mody in 1993.

Ratan Tata, on that occasion, had said that Tisco would not be affected by Mody’s exit. To this Mody had replied “Ratan is quite right. No one is indispensable. My disappearance from Jamshedpur may not be felt, but the arrival of Ratan Tata and (JJ) Irani will certainly make a difference. It’s all like a circus — the serious acts of entertainment are always shown first. Then come the clowns and the animal trainers. That may well be the case with Tisco.” (quoted in Russi Mody: The Man Who Also Made Steel, written by Partha Mukherjee and Jyoti Sabharwal).

That was uncharitable, but Mody was quite off the mark on this.

Ill-health forced Nani Palkhivala to leave (he was later affected by Alzheimer’s disease). Other biggies like Darbari Seth and Ajit Kerkar were forced out by implementing a long dormant retirement rule. It is the same retirement rule that Tata has now implemented for himself and appointed Cyrus Mistry in his place.

The other thing that Ratan Tata did was increase the holdings of Tata Sons in all group firms to 26 percent, the level which allows a shareholder to block resolutions at the board level. As Ratan Tata told Witzel in Tata – The Evolution of a Corporate Brand: “Then we set ourselves the task of seeing how we could put ourselves together as a more meaningful and recognisable group of companies with more central control.”

The money required for increasing stakes in various group companies came from Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) which had become the largest software company in Asia and was generating a phenomenal amount of cash for Tata Sons. TCS was a success story that had come out of JRD’s philosophy of allowing his managers to do their own thing. And since the company was unlisted back then, Tata Sons owned it fully.

The other thing that Ratan Tata did was to make the Tata brand more visible and uniform. “One of the first steps in the establishment of the Tata corporate brand was the harmonisation of the brand mark as it was used. As Ratan Tata says, ‘You could fill a wall with the different symbols used by the companies’. These were now swept away and a uniform style was introduced,” writes Witzel.

Also company names like Tisco and Telco were changed to Tata Steel and Tata Motors to make the Tata connection more explicit. Strong brand names like the Taj Mahal hotel were not changed. The group companies were also made to sign the Tata code of conduct. This also meant paying Tata Sons a subscription fees of 0.25 percent of their annual sales, if the companies used the Tata brand name directly.

The other big decision of Ratan Tata was to get Tata firms to go global. When Ratan Tata took over only around 5 percent of the group’s revenues used to come from overseas operations. Now the number is at 58 percent.

A 2007 story by Business Week magazine best describes Tata’s international forays. “Since 2003, Tata has bought the truck unit of South Korea’s Daewoo Motors, a stake in one of Indonesia’s biggest coal mines, and steel mills in Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. It has taken over a slew of tony hotels, including New York’s Pierre, the Ritz-Carlton in Boston, and San Francisco’s Camden Place. The 2004 purchase of Tyco International’s undersea telecom cables for $130 million, a price that in hindsight looks like a steal, turned Tata into the world’s biggest carrier of international phone calls. With its $91 million buyout of British engineering firm Incat International, Tata Technologies now is a major supplier of outsourced industrial design for American auto and aerospace companies, with 3,300 engineers in India, the US, and Europe.

The crowning deal to date has been Tata Steel’s $13 billion takeover in April of Dutch-British steel giant Corus Group, a target that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. In one swoop, the move greatly expands Tata Steel’s range of finished products, secures access to automakers across the US and Europe, and boosts its capacity fivefold, with mills added in Pennsylvania and Ohio.” (You can read the complete story here).

If all that wasn’t enough in 2008 Tata Motors also bought iconic British car brands the Jaguar and the Land Rover.

This strategy of Tata has come in for some criticism given that a lot of companies were bought during 2003-2008 when prices were at their peak. While this is correct with the benefit of hindsight, it also needs to be pointed out that it is easier to carry out big deals in a bull market when people are willing to sell and finance is easier to raise.

On the home front the group has entered newer business like Tata Sky (direct-to-home television) and Ginger Hotels (budget hotels). But Ratan Tata’s big dream has been the Tata Nano, an affordable car for the average Indian. He had the idea to build a car like Nano when he saw a family of four struggling on a two-wheeler on a rainy night in Mumbai.

The car has run into a spate of controversies. The Tatas had to pull out of West Bengal where the Nano was originally supposed to be made after political trouble erupted there. They have since moved manufacturing to Gujarat. Other than that, the quality of the initial batch has been criticised with some cars catching fire. But more than anything the car which was supposed to cause traffic jams all across India isn’t really selling too well. Nevertheless it is too early to write off the Nano. (You can read the complete story here). Ratan Tata, for one, believes there is life to the Nano and he could be right.

Ratan Tata’s stint at the Tata group is now coming to an end. He is set to retire in December when he turns 75. As he attends his last annual general meeting of Tata Global Beverages today (31 August 2012 in Kolkata), he can look bank in wonder at what he has created over the 20-and-odd-years he has captained the group. The total revenues of the Tata Group in 2010-2011 were around $83 billion,many more times what it was when Ratan Tata took over the group way back in 1991.

Tata has remained a bachelor all his life though, in an interview to CNN in April 2011, he admitted that he came close to marrying four times. “When you asked whether I’d ever been in love, I came seriously close to getting married four times and each time it got close to there and I guess I backed off in fear of one reason or another,” he said.

The most serious affair was when Tata was in the United States. “Well, you know one was probably the most serious was when I was working in the US and the only reason we didn’t get married was that I came back to India and she was to follow me… and that was the year of the, if you like, the Sino-Indian conflict and in true American fashion this conflict in the Himalayas, in the snowy, uninhabited part of the Himalayas, was seen in the United States as a major war between India and China and so, she didn’t come and finally got married in the US thereafter,” he had told CNN.

Tata, like his uncle JRD, is an avid pilot and is known to fly the Falcon 2000 business jet on his own within India. In the Aero India 2007 air show Tata co-piloted the fighter jets Lockheed F-16 and Boeing F-18.

He has a younger brother Jimmy about whom not much is known. He also has one step brother Noel (who heads the retail business of the Tata group) and three step sisters, one of whom is married to the next Tata Sons Chairman Cyrus Mistry.

Mistry also happens to be the son of Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry, the largest individual shareholder of Tata Sons. Given this, chances are that Ratan Tata may be the last Tata at the helm of the Tata group.

However, as Gita Piramal noted earlier, one needn’t be born a Tata to be its head. Tata is about a state of mind, not just being born in India’s most respect business family.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 31,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/ta-ta-how-ratan-rebuilt-the-house-that-jrd-left-him-437593.html)

Where does inspiration end and plagiarism begin?

Vivek Kaul

So all’s well that ends well. Fareed Zakaria is back in business. But the question that remains is what is plagiarism and what is not? Where does inspiration end and plagiarism start? Let’s explore these questions in the context of music and films, both international as well as Indian, and journalism.

As I write this I am listening to the song “Papa Kehte Hain Bada Naam Karega,” from the movie Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak. The song starts of sounding very similar to an old Roy Orbison song “O Beautiful Lana” but changes track after that and acquires an identity of its own.

The composers Anand-Milind may have clearly been inspired by Roy Orbison in the way they composed the song, but they hadn’t plagiarized.

The bestselling author Malcolm Gladwell in an essay titled Something Borrowed – Should a Charge of Plagiarism Ruin Your Life? tries to examine the questions I raised at the beginning of this piece. He describes an experience that he had with a musically inclined friend of this.

As Gladwell writes “He played Led Zeppelin’s “Whotta Lotta Love” and then Muddy Water’s “You Need Love,” to show the extent to which Led Zeppelin had mined the blues for inspiration…He played “Last Christmas” by Wham! followed by Barry Manilow’s “Can’t Smile Without You” to explain why Manilow might have been startled when he first heard the song.” (You can listen to Can’t Smile Without You here and Last Christmas here)

Gladwell talks about the famous heavy metal band Nirvana and their inspiration. ““That sound you hear in Nirvana,” my friend said at one point, “that soft and then loud kind of exploding thing, a lot of that was inspired by the Pixies. Yet Kurt Cobain” –Nirvana’s lead singer and songwriter – “was such a genius that he managed to make its own. And “Smells Like Teen Spirit’?” – here he was referring to perhaps the best-known Nirvana song. “That’s Boston’s ‘More Than a Feeling.’” He began to hum the riff of the Boston hit, and said, “The first time I heard ‘Teen Spirit,’ I said, ‘That guitar lick is from “More Than a Feeling.”’ But it was different – it was urgent and brilliant and new.”

So what this tells us is that a lot of good old music formed the base of a lot of good new music. But does that imply plagiarism? Clearly not!

Let us look at some examples from closer to home. Talat Mehmood once sang a song “Hain sab se madhur geet wohi jo hum dard ke suron main gaate hain.” This song from the movie Patita was written by Shailendra and set to tune by Shankar Jaikishan. Those who know their English poetry well, will know, that this song is clearly inspired from P B Shelley’s poem To a Skylark, in which he wrote “Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.”

Or take the case of the song “Jab hum honge 60 saal ke aur tum hoge 55 ke,bolo preet nibhaogee na phir bhi apne bachpan ki” from Randhir Kapoor’s directorial debut Kal, Aaj aur Kal. Any guesses on what is the inspiration for this song? It is the Beatles number “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I am 64?”

In both these cases something new was created from something that was already in existence. Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal explore the difference between inspiration and plagiarism in their brilliant book R.D.Burman – The Man, The Music. As they write “The pièce de résistance of Shaan was the title song, ‘Pyar karne waale pyar karte hain shaan se,’…The recurring beat in the song could have been inspired, in part, from ‘I feel love’ by Donna Summers, but the song in itself was multidimensional, a grand mix of Asha’s voice and a host of instruments, and bore no resemblance to the Donna Summer hit.” (You can listen to I feel love here).

RD Burman was accused of plagiarising right through his career. “Right through his career, this was probably one question that Pancham had to defend himself against, in most of his interviews, and he often clarified that inspiration was part of the game in any field of art and that his rule was to use one line and recreate an entire song out of the same, something that most composers did,” write Bhattacharjee and Vittal. “Pancham’s stand against charges of plagiarism was matter-of-fact; he did not go out to copy tunes if given the chance to operate on his own terms. He might have needed a start, only to help him trudge along,” the authors add.

There was a lot of inspiration that went into the composition of 1942-A Love Story, RD Burman’s swansong. “With ‘Ek ladki ko dekha’, he got on to the full-on mukhra-antara style that his father once pioneered in ‘Borne gondhe chhonde geetitey’ (the original tune for ‘Phoolon ke rang se’ in Dev Anand’s Prem Pujari), where the mukhra and the antara are merged as one… ‘Kuch na kaho’ found Pancham fleetingly referencing the tune of SD’s ‘Rongila rongila’ (SD as in SD Burman, RD’s father) and giving it a totally different colour and contour, with an orchestration bordering on the symphonic…RD went back to Indian classical music and Rabindranath Tagore for ‘Dil ne kaha chupke se’, basing it on the dual inspiration of Raga Desh and Tagore’s ‘Esho shyama sundaro’, and using strains from ‘Panna ki tamanna‘ (Heera Panna) and ‘Aisa kyon hota hai’ (Ameer Aadmi Garib Aadmi,1985),” the authors point out.

So clearly even the best musicians are inspired when they do their best work. The same stands true for cinema as well. Take the case of “Manorama Six Feet Under.” I saw the movie when it was released and was impressed. The screenplay, dialogues, music, performances…everything about the movie was brilliant. Then I read in a review that the movie was copied from Roman Polanski’s 1974 Jack Nicholson starrer Chinatown.

I managed to locate a VCD of the movie sometime later and happened to see it. Broadly speaking, yes Manorama is a copy of Chinatown. The story is more or less the same. But Navdeep Singh the director of the movie has managed to Indianise it very well. And Manorma‘s end is brilliant, much better than Chinatown‘s vague arty ending. Of course, Manorma does not have the incest angle to the story that Chinatown had.

Now this was a clear case of a director who was inspired. Yes he copied, but I don’t think he plagiarised.

So the distinction between plagiarism and inspiration is not always easy to draw. Malcolm Gladwell makes the point when he writes about something that most journalists have to do at some point of time. As he writes “When I worked at a newspaper, we were routinely dispatched to “match” a story from the Times (I presume Gladwell means the New York Times here): to do a new version of someone else’s idea. But had we “matched” any of the Times’ words – even the most banal of phrases – it could have been a firing offence. The ethics of plagiarism have turned into the narcissism of small differences: because journalism cannot own up to its heavily derivative nature, it must enforce originality only on the level of sentence.”

This is a very important point that Gladwell makes furthering the point that in many cases it is difficult to distinguish what is plagiarism and what is not.

But that is not always the case. Musicians like Bappi Lahiri and Annu Mallik made a career out of plagiarising western tunes. So did Anand-Milind by copying Ilaiyaraaja. The same is true about Sanjay Gupta’s Kaante. It is a shameless copy of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. In fact Anurag Kashyap, the dialogue writer for the film even admitted in an interview that he was given the DVD of Reservoir Dogs and asked to translate the dialogues. So much for being creative. Sanjay Gupta’s Zinda is also a scene by scene lift of the Korean Movie Old Boy even though Gupta claimed that “international films” inspired him.

So that brings me back to the question that I have been trying to answer “Where does inspiration end and plagiarism start?” The answer to this most likely is: It is a very individual thing. Every creative individual knows where inspiration ends and plagiarism starts. As Justice Potter Stewart, a US judge, wrote in Jacobellis versus Ohio (1964), “I cannot define pornography, but I know it when I see it.”

It’s the same with plagiarism.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 29,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/living/where-does-inspiration-end-and-plagiarism-begin-435291.html

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

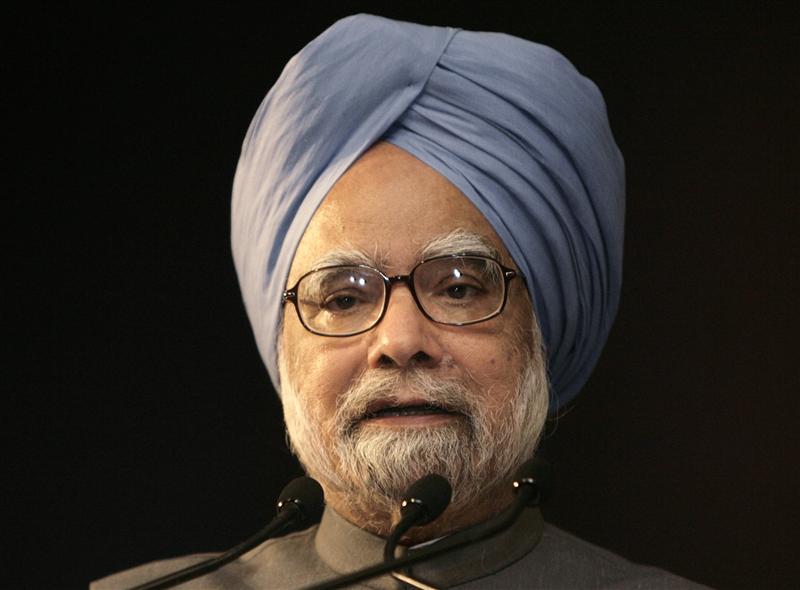

Why Manmohan Singh was better off being silent

Vivek Kaul

So the Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh has finally spoken. But there are multiple reasons why his defence of the free allocation of coal blocks to the private sector and public sector companies is rather weak.

“The policy of allocation of coal blocks to private parties…was not a new policy introduced by the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). The policy has existed since 1993,” the PM said in a statement to the Parliament yesterday.

But what the statement does not tell us is that of the 192 coal blocks allocated between 1993 and 2009, only 39 blocks were allocated to private and public sector companies between 1993 and 2003.

The remaining 153 blocks or around 80% of the blocks were allocated between 2004 and 2009. Manmohan Singh has been PM since May 22, 2004. What makes things even more interesting is the fact that 128 coal blocks were given away between 2006 and 2009. Manmohan Singh was the coal minister for most of this period.

Hence, the defence of Manmohan Singh that they were following only past policy falls flat. Given this, giving away coal blocks for free is clearly UPA policy. Also, we need to remember that even in 1993, when the policy was first initiated a Congress party led government was in power.

The PM further says that “According to the assumptions and computations made by the CAG, there is a financial gain of about Rs. 1.86 lakh crore to private parties. The observations of the CAG are clearly disputable.”

What is interesting is that in its draft report which was leaked earlier in March this year, the Comptroler and Auditor General(CAG) of India had put the losses due to the free giveaway of coal blocks at Rs 10,67,000 crore, which was equal to around 81% of the expenditure of the government of India in 2011-2012.

Since then the number has been revised to a much lower Rs 1,86,000 crore. The CAG has arrived at this number using certain assumptions.

The CAG did not consider the coal blocks given to public sector companies while calculating losses. The transaction of handing over a coal block was between two arms of the government. The ministry of coal and a government owned public sector company (like NTPC). In the past when such transactions have happened revenue from such transactions have been recognized.

A very good example is when the government forces the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India to forcefully buy shares of public sector companies to meet its disinvestment target. One arm of the government (LIC) is buying shares of another arm of the government (for eg: ONGC). And the money received by the government is recognized as revenue in the annual financial statement.

So when revenues from such transactions are recognized so should losses. Hence, the entire idea of the CAG not taking losses on account of coal blocks given to pubic sector companies does not make sense. If they had recognized these losses as well, losses would have been greater than Rs 1.86lakh crore. So this is one assumption that works in favour of the government. The losses on account of underground mines were also not taken into account.

The coal that is available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But the entire coal cannot be mined due to various reasons including those of safety. The part that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve. The extractable reserves of these blocks (after ignoring the public sector companies and the underground mines) came to around 6282.5 million tonnes. The average benefit per tonne was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated August 21, 2012,”The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs1028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL(Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the Ministry of Coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012 a further allowance of Rs150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly the average benefit of Rs295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6282.5 million tonne calculated as above.”

Using this is a very conservative method CAG arrived at the loss figure of Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes).

Manmohan Singh in his statement has contested this. In his statement the PM said “Firstly, computation of extractable reserves based on averages would not be correct. Secondly, the cost of production of coal varies significantly from mine to mine even for CIL due to varying geo-mining conditions, method of extraction, surface features, number of settlements, availability of infrastructure etc.”

As the conditions vary the profit per tonne of coal varies. To take this into account the CAG has calculated the average benefit per tonne and that takes into account the different conditions that the PM is referring to. So his two statements in a way contradict each other. Averages will have been to be taken into consideration to account for varying conditions. And that’s what the CAG has done.

The PM’s statement further says “Thirdly, CIL has been generally mining coal in areas with

better infrastructure and more favourable mining conditions, whereas the coal blocks offered for captive mining are generally located in areas with more difficult geological conditions.”

Let’s try and understand why this statement also does not make much sense. As The Economic Times recently reported, in November 2008, the Madhya Pradesh State Mining Corporation (MPSMC) auctioned six mines. In this auction the winning bids ranged from a royalty of Rs 700-2100 per tonne.

In comparison the CAG has estimated a profit of only Rs 295.41 per tonne from the coal blocks it has considered to calculate the loss figure. Also the mines auctioned in Madhya Pradesh were underground mines and the extraction cost in these mines is greater than open cast mines. The profit of Rs 295.41was arrived at by the CAG by considering only open cast mines were costs of extraction are lower than that of underground mines.

The fourth point that the PM’s statement makes is that “Fourthly, a part of the gains would in any case get appropriated by the government through taxation and under the MMDR Bill, presently being considered by the parliament, 26% of the profits earned on coal mining operations would have to be made available for local area development.”

Fair point. But this will happen only as and when the bill is passed. And CAG needs to work with the laws and regulations currently in place.

A major reason put forward by Manmohan Singh for not putting in place an auction process is that “major coal and lignite bearing states like West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and Rajasthan that were ruled by opposition parties, were strongly opposed to a switch over to the process of competitive bidding as they felt that it would increase the cost of coal, adversely impact value addition and development of industries in their areas.”

That still doesn’t explain why the coal blocks should have been given away for free. The only thing that it does explain is that maybe the opposition parties also played a small part in the coal-gate scam.

To conclude Manmohan Singh might have been better off staying quiet. His statement has raised more questions than provided answers. As he said yesterday “Hazaaron jawabon se acchi hai meri khamoshi, na jaane kitne sawaalon ka aabru rakhe”.For once he should have practiced what he preached.

(The article originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 29,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/column_why-manmohan-singh-was-better-off-being-silent_1734007))

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

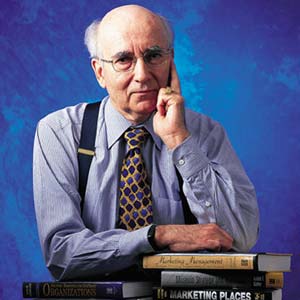

‘The theory of maximizing “shareholder value” has done great harm to businesses’

He is 81 and still going strong. His text book on marketing: Marketing Management is now in its thirteenth edition and still remains an essential read for anyone who hopes to get an MBA degree. He’s often called the father of marketing; something he regards as a compliment, while at the same time ceding the title of the “grandfather of marketing” to management thinker Peter Drucker. Meet Philip Kotler, the S.C. Johnson & Son Distinguished Professor of International Marketing at the Northwestern University Kellogg Graduate School of Management in Chicago. He has been hailed by Management Centre Europe as “the world’s foremost expert on the strategic practice of marketing.” In this freewheeling interview he talks to Vivek Kaul.

Excerpts:

Historically, the vast majority of marketing campaigns have been designed to appeal to our personal needs, lusts, greed or insecurities. To what extent do marketers exploit our human tendencies toward addiction?

Professional marketers see customers as carrying on both mental and emotional processes as they consider purchasing anything. Marketers need to choose the emotional appeal(s) that are relevant to the particular product or service. For a toothpaste, the appeal might be better breath, whiter teeth, or fewer cavities. Or going further, the appeal might be looking sexier, or having longer term dental health. Each competitor must make a choice. In a campaign to get people to stop smoking, one can use a negative appeal (cancer, lung disease, kidney failure) or a positive appeal (better sports performance, living longer for your family). I have advocated using an anti-smoking appeal showing a father who puts out his cigarette when his child comes into view so as not to pass on this bad habit to his children (this is a love appeal). Human emotions range widely and the choice of an appeal is a careful decision that is conditioned by competitors’ appeals and other data. It might seem to the layman that ads often use sex, power, or ego appeals but we could cite many campaigns that use appeals that are less base.

Lately companies have been cutting their marketing budgets, given the troubled times that we are in. Do you think it is a wise move to cut the marketing budget?

That is a panic response and often inappropriate. If competitors decide to cut their marketing budgets, the remaining firm should consider keeping or even increasing its marketing budget. I would go further and sat that a well-heeled firm might even consider buying out some weaker firms during a recession. In normal times, a company finds it hard to move its market share. In recession times, a well-endowed firm can power up its market share. Much depends on the quality of the firm’s products and services. A market leader should consider adding more value rather than cutting its marketing budget. The leader will probably have to alter its messages and media but it doesn’t follow that it needs to cut its marketing budget.

The economist Milton Friedman famously said: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits”. What are your thoughts on the social responsibility of marketing?

Milton Friedman was my professor at the University of Chicago and we all admired his brilliance. He was a great believer in leaving businesses unencumbered by regulations and he wanted the leave the business owners to decide what they wanted to do with their profits. I took exception to this view.

Why was that?

Businesses are social organizations that can do great good or great harm. We don’t have to be reminded of the environmental damage companies did by dumping waste into water and pollutants into the air. We don’t have to be reminded of Enron and Madoff and other crooks and pyramid builders. We need appropriate regulations for the competitive system to work. I would argue that companies should go beyond their worship of shareholders who often don’t care about the company and jump in and out of owning its stock. The theory of maximizing “shareholder value” has done great harm to businesses. I have argued that smart companies must focus on the other stakeholders first – customers, employees, suppliers and distributor—and make sure that these stakeholders are all rewarded appropriately and that they work together as a winning team. Satisfying the stakeholders is the best way to maximize the long run profitability of the company. I would propose that as education levels rise in a country, more buyers will expect more from companies and base their brand choices partly on which companies have practiced a caring attitude toward the environment and society. Those companies that operate on the triple bottom line — people, planning and profits – will outperform those who only pursue profit.

A major point in your new book Good Works: ! Marketing and Corporate Initiatives that Build a Better World…and the Bottom Line, is that over the last decade there has been tremendous growth in the number of marketing and corporate initiatives that appeal to our desire to help others or tackle social or environmental problems. Why has this sudden change come about? Can you share some examples with us?

Let’s recognise that societies are facing a growing number of difficult problems – world hunger and poverty, local wars, pollution, environment damage, and faulty education and health systems. Solutions are badly needed. Solutions can only come from the three sectors found in any economy: businesses, NGOs, and government. Today, the governments in most countries are in no condition to solve these problems, given their debt levels and their political impasses. The NGOs have as their purpose to help solve these social problems but are even with less funds available in these recessed times. Business is the only agent of change with the means of doing something to improve the sad state of affairs. The public is increasingly interested in which companies are willing to help make a difference in some of these problems. Consider what Wal-Mart is doing now to reduce air pollution. It is not only ordering the most fuel efficient delivery trucks but now asking its suppliers to change to more efficient trucks or else not be accepted as a supplier. Timberland, the maker of shoes and clothing, does a thorough job of waste reduction and of choosing only suppliers who have good environmental practices. The message is that companies have the capacity to be proactive in making the world a better place for all of us.

What do think are the biggest challenges facing marketing today?

Marketing used to be pretty straight forward. Hire able salespeople and brand managers and a top advertising agency and the team will attract many triers and buyers. Marketers didn’t have much input into the product: their job was to get the product sold. Today the picture is radically different. The social media revolution has diminished the power of advertising and requires new skills in the marketing group to successfully use Facebook, You Tube, Linked in, and Twitter. Buyers are now all-knowing thanks to Google and their Facebook friends and they can get excellent information on different brands and their worth. Companies have to make a basic decision: Should the marketing department basically remain a communication group (one P – Promotion), or a 4P group (Product, Price, Place and Promotion)? I am in favor of giving marketing more power to participate in the product development process, and pricing, and place (distribution decisions).

Could you elaborate on that?

I would go further. The ideal marketing department would be headed by someone with the mindset of Steve Jobs. The Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) would be responsible for identifying the best opportunities for the business for the next five years, calibrating the profitability of the different opportunities, and participating with the other senior officers to make the right choices. The marketing group should know more about what is happening in the marketplace and what is likely to happen over the next few years and therefore be in a position to visualise where the business should be going. I remember that some years ago, GE asked its appliance marketing group to anticipate what will be the size and activities in kitchens in the next five years. The marketers came up with a great number of new ideas, many of which GE Appliance implemented. So the basic choice is whether marketing should remain largely a “service” department dishing out communications or it should be a proactive marketing group helping the company identify its best future opportunities. I sometimes say that a company should have two marketing departments: a large one that is busy selling what the company is making , and a smaller marketing group trying to figure out what the company ought to be making the in the coming years.

What is social marketing? Can you share some examples with us?

In July 1971, Professor Gerald Zaltman and I published “Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change” in the Journal of Marketing. The question was: “could you sell a cause the way we sell soap.” At the time, there was a lot of interest in how we could help people avert unwanted pregnancies, stop smoking, and say no to drugs. We could imagine creating ads that would change certain beliefs and behaviours. We could imagine making new products and services that would provide solutions in these problem areas. We could imagine distribution arrangements that would reduce the accessibility of unsalutory products or increase the availability of better substitute products and services. We could imagine using price to encourage or discourage certain behaviors. All four Ps would work on these social questions as they have worked in the commercial market.

And things have changed since then?

Since that time, social marketing has become another branch of marketing. There are over 2,000 social marketers operating in the world and addressing social causes of poverty and hunger, health, environment, education, littering, literacy and others. Social marketers don’t stop with advertising: they use a planning framework that applies the ideas of segmentation, targeting and positioning and the 4Ps to craft a workable social marketing plan. Dozens of social marketing examples are described in the 4th edition of Social Marketing that Nancy Lee and I published. There is now a hotline where social marketers interested in working on some social problem can put it out to other social marketers to learn of previous work and results in the same problem area. I believe that social marketing methodology has been a major contributor to the decline of smoking, the practice of birth control, the improvement of the environment, the providing of more health facilities and practitioners in poor countries, and rising rates of literacy.

Your basic training is as an economist. How did you move on to marketing?

Marketing is economics, even if many trained economists don’t recognise or read marketing and ignore the one hundred years of marketing writing. As I majored in economics at the University of Chicago (M.A.) and M.I.T. (Ph.D), I was impressed with the high level of theory but disappointed at the neglect of the real actions taking place in the marketplace. Classical economists didn’t say much about several key forces affecting demand such as sales force, advertising, sales promotion, and public relations. Economists focused mainly on price and how it affects demand and supply. They didn’t say much about distribution and the roles played by wholesalers, jobbers, retailers, agents, brokers and other transactional and facilitating forces. In fact, the first marketing books written around 1910 were written primarily by economists who wanted to bring the role of Promotion and Place into the understanding of markets. Even when economists discussed price, they rarely described how price is set separately by manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers as price setting moves down the value chain.

So how did you move onto teaching marketing?

When I joined the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, I was given a choice to teach either economics (macro or micro) or marketing. I chose marketing because it brought in all these additional forces that affect demand and supply. Earlier I was in a Ford Foundation program with Jerry McCarthy who was writing his textbook on Basic Marketing and proposing a 4P framework: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. He was influenced by his professor of marketing at Northwestern University, Richard Clewett who taught Product, Price, Promotion and Distribution (which Jerry renamed Place to get the alliteration of 4Ps). Remember that the 4Ps are demand-shaping forces and should be part of basic economic theory. The interesting development today is that classical economics is undergoing the challenge of a different school of thought, namely behavioural economics. Behavioral economics drops the assumption that producers, middlemen and consumers always make rational decisions. At best there is “bounded rationality” and “satisficing” behavior rather than rational profit maximization. What is most interesting is that “behavioural economics” is just another name for “marketing” and what marketing has been researching for 100 years.

How do you manage to write about marketing from almost every angle?

I recognised early that marketing is a pervasive human activity that goes beyond just trying to sell goods and sales. What is courtship, after all, if not a marketing exercise? What is fundraising, if not a marketing exercise? What about building a stronger brand for your city, if not a marketing exercise? Every celebrity and many professionals are engaged in building and marketing their brand. This led me to want to bridge marketing theory and practice to other things than goods and services. I started to research and write on place marketing, person marketing, cultural areas marketing (museums and performing arts), cause marketing (i.e., social marketing), religious institution marketing, and so on.

(The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 27,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/interview_theory-of-maximising-shareholder-value-has-done-great-harm-to-businesses_1733089))

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])