This column is slightly different from the ones I usually write. On most days the idea is to write on something which is currently happening. This column doesn’t fit that formula.

In this column I wanted to write about how our world view plays a huge part in what we think and the decisions that we make, and how those decisions can turn out to be majorly wrong in the long-term, even though when we were making them they seemed to be the perfectly correct thing to do.

The dotcom bubble started to burst in early 2000. Soon after on September 11, 2011, several airliners were hijacked, of which two flew into the iconic World Trade Center in New York and one into Pentagon. The American economy which was going through tough times in the aftermath of the dotcom bubble collapsing, got into even more trouble after 9/11.

Alan Greenspan, who was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of the United States, at that point of time, recalls in his book The Age of Turbulence that the American economy had been in a minor recession for a period of seven months before September 2001. And in the aftermath of the attacks, the reports and statistics streaming in painted a very worrying picture.

Americans had stopped spending on everything other than the items they would need in case there were more attacks. Sales of grocery items had gone up; so had sales of security devices, insurance, and bottled water. On the flip side, businesses like travel, entertainment, hotels, tourism, and even automobiles were majorly hit.

The American economy is very consumer driven and if consumers stop spending, then the economic growth immediately collapses. This was likely to happen in the months that followed September 2001.

With spending collapsing, there was a danger of the minor recession turning into a major one. To prevent this, Greenspan, as he had in the past, decided to cut interest rates. The federal funds rate, which was at 3.5 percent before the attack, was cut four times and brought down to 1.75 percent by the end of the year, starting with the first rate cut of 50 basis points, or half a percentage point, on September 17, 2001, six days days after the attack. (One basis point is one hundredth of a percentage). The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which one bank lends funds maintained at the Federal Reserve to another bank on an overnight basis. It acts as a sort of a benchmark for the interest rates that banks charge on their short and medium term loans.

Central banks cut interest rates in the hope that consumers would borrow money to spend and businesses would borrow money to expand, and so the economy would grow. As James Rickards writes in The Death of Money—The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System: “We all asked ourselves how we could help [in the aftermath of the attack]. The only advice we got from Washington was ‘get down to Disney World … take your families and enjoy life’.”

People did borrow and spend, but they went overboard with it. America’s new bubble after dot-com was real estate and it was built on the belief that anyone could make money in real estate. As Stephen D. King puts it in When the Money Runs Out: “The white heat of the 1990s technological revolution was replaced by the stone cold of a housing boom.”

Between January 2001 and mid-2003, the federal funds rate was cut by 550 basis points to one percent. The interest rate stayed at one percent for little over a year.

The Federal Reserve did not want the United States to become another Japan. Japan had been in a low growth environment since the collapse of the stock market and the real estate bubbles, starting in late 1989. Prices had been regularly falling. In an environment of falling prices(or deflation) consumers keep postponing consumption in the hope of getting a better deal in the future. This leads to businesses suffering and the economic growth collapsing.

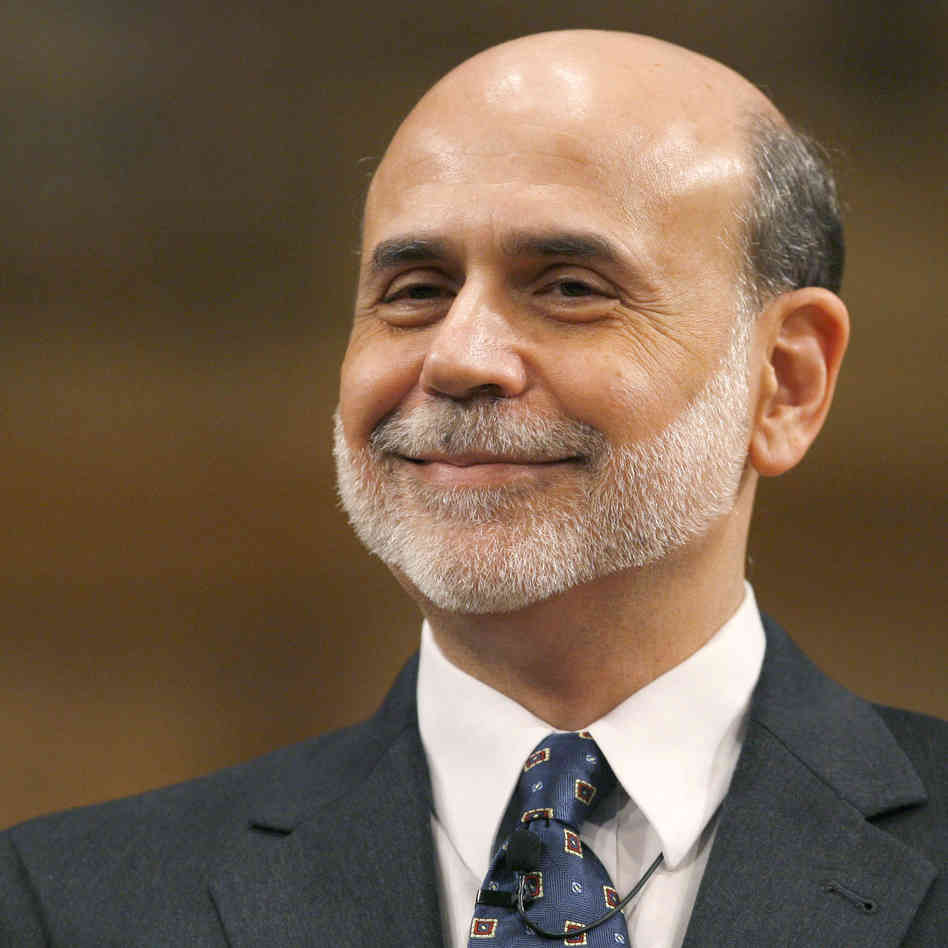

Ben Bernanke, who would takeover as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve from Alan Greenspan in 2006, joined the Federal Reserve in 2002 as a governor. Bernanke was a scholar on the Great Depression of 1929.

In one of the first speeches that Bernanke made after joining the Federal Reserve he said: “Whenever we read newspaper reports about Japan, where what seems to be a relatively moderate deflation—a decline in consumer prices of about 1 percent per year—has been associated with years of painfully slow growth, rising joblessness, and apparently intractable financial problems in the banking and corporate sectors … the consensus view is that deflation has been an important negative factor in the Japanese slump… I believe that the chance of significant deflation in the United States in the foreseeable future is extremely small… So, having said that deflation in the United States is highly unlikely, I would be imprudent to rule out the possibility altogether.”

This fear of not becoming another Japan and at the same time not engineering another Great Depression led to the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low much longer than it should have. This led to the real estate bubble which would finally start bursting in 2007-2008.

As Barry Eichengreen writes in his brilliant new book Hall of Mirrors—The Great Depression, The Great Recession and The Uses—And Misuses—Of History: “With benefit of hindsight, we can say that the Fed overestimated the risk of deflation and responded too preemptively and aggressively. As a student of Japan and of the Great Depression, Bernanke may have been overly sensitive to the danger of deflation at this point of time. In other words, history may be useful for informing the views of policy makers of how to respond to certain risks, but it may also shape and inform outlooks in ways that heighten other risks”

Bernanke’s world view led to the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low much longer than it should have. Over and above this, the inflation data that was coming out at that point of time may also have had a role to play. As Eichengreen writes: “Distorted data may have also contributed to the Fed’s exaggerated concern with deflation. Contemporaneous data showed the personal consumption expenditure deflator[the inflation index that the Federal Reserve follows], cleansed of volatile food and fuel prices, falling to less than 1% in 2003, dangerously close to negative territory. Subsequent revisions revealed that inflation in fact had already bottomed out at 1.5% and was now safely on the rise.”

This led to Federal Reserve maintaining low interest rates, when it should have been raising them. In the process, the Fed ended up fuelling the real estate bubble, which finally led to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, and the start of the current financial crisis, which was followed by what is now known as the Great Recession.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on May 29, 2015