Vivek Kaul

John Brooks in his brilliant book Business Adventures writes “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions!” One country on which this sentence applies the most is Japan. The country has been trying to come out of a bad economic scenario for two decades and it only keeps getting worse for them, despite the effort of its politicians and its central bank.

In the previous column, I wrote about how the prevailing economic scenario in Japan will ensure that they will continue with the “easy money” policy in the days to come, by printing money and maintaining low interest rates in the process.

But it looks like the situation just got worse for them. The Japanese economy contracted at an annual rate of 1.6% during the period July-September 2014. This after having contracted at an annual rate of 7.1% in April-June 2014. Two consecutive quarters of economic contraction constitute a recession.

Shinzo Abe was elected the prime minister of Japan in December 2012. His immediate priority was to create some inflation in Japan in order to get consumer spending going again. The Bank of Japan cooperated with Abe on this, and decided to print as much money as would be required to get inflation to 2%. This policy came to be referred as “Abenomics”.

In April 2013, the Bank of Japan decided to print $1.4 trillion and use it to buy bonds, and hence, pump that money into the financial system. The size of the Japanese economy is around $5 trillion. Hence, as a proportion of the size of Japan’s economy, this money printing effort was twice the size of the Federal Reserve’s third round of money printing, more commonly referred to as the third round of quantitative easing or QE-III.

Sometime in April this year, the Abe government decided to increase the sales tax from 5% to 8%. The idea again was to raise prices, by introducing a tax, and get people to start spending again. Nevertheless, this backfired big time and the economy has now contracted for two consecutive quarters. Elaine Kurtenbach writing for the Huffington Post points out “Housing investment plunged 24 percent from the same quarter a year ago, while corporate capital investment sank 0.9 percent. Consumer spending, which accounts for about two-thirds of the economy, edged up just 0.4 percent.”

Towards the end of October 2014, the Bank of Japan decided to print $800 billion more because the inflation wasn’t rising as the central bank expected it to. Now with the economy contracting again, there will be calls for more money printing and economic stimulus. In fact, after GDP contraction number came out, Etsuro Honda, an architect of Abenomics, told the Wall Street Journal that it was “absolutely necessary to take countermeasures.”

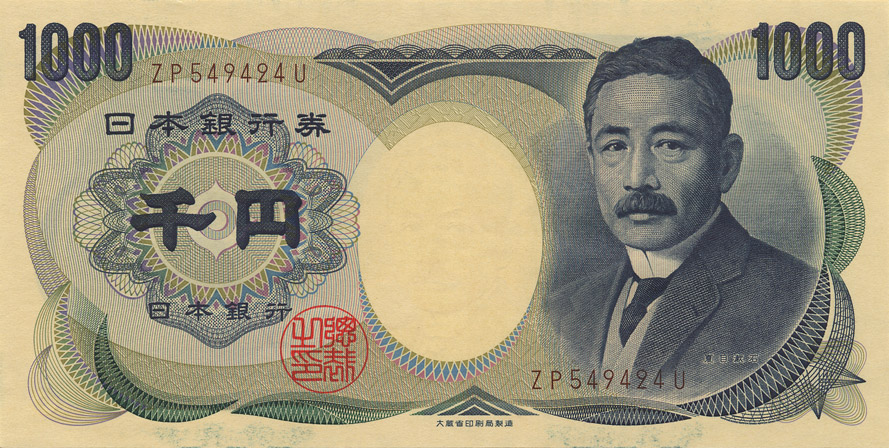

While the “easy money” policy run by the Japanese government and the central bank hasn’t managed to create much inflation, it has led to the depreciation of the yen against the dollar and other currencies.

In early November 2012, before Shinzo Abe took over as the prime minister of Japan, one dollar was worth 79.4 yen. Since then, the yen has constantly fallen against the dollar and as I write this on the evening of November 18, it is worth around 117 to a dollar.

Interestingly, some inflation that has been created is primarily because of yen losing value against the dollar. This has made imports expensive. The consumer price inflation(excluding fresh foods) for the month of September 2014 came in at 3%. Once adjusted for the sales tax increase in April, this number fell to a six month low of 1%, still much below the Bank of Japan’s targeted 2% inflation.

Analysts believe that the yen will keep losing value against the dollar in the time to come. John Mauldin wrote in a recent column titled The Last Argument of Central Bankers “The yen is already down 40% in buying power against a number of currencies, and another 40-50% reduction in buying power in the coming years is likely, in my opinion.”

Albert Edwards of Societe Generale is a little more direct than Mauldin and wrote in a recent research report titled Forecast timidity prevents anyone forecasting ¥145/$ by end March – so I will “The yen is set to…[crash] through multi-decade resistance – around ¥120. It seems entirely plausible to me that once we break ¥120, we could see a very quick ¥25 move to ¥145 [by March 2015].”

Edwards further writes that he expects “the key ¥120/$ support level to be broken soon and the lows of June 2007 (¥124) and Feb 2002 (¥135) to be rapidly taken out.” The note was written before the information that the Japanese economy had contracted during July-September 2014, came in.

This makes the Japanese yen a perfect currency for a “carry trade”. It can be borrowed at a very low rate of interest and is depreciating against the dollar. Before we go any further, it is important that we go back to the Japan of early 1990s.

The Bank of Japan had managed to burst bubbles in the Japanese stock and real estate market, by raising interest rates. This brought the economic growth to a standstill.

After bursting the bubbles by raising interest rates, the Bank of Japan had to start cutting interest rates and soon the rates were close to 0 percent. This meant that anyone looking to save money by investing in fixed-income investments (i.e., bonds or bank deposits) in Japan would have made next to nothing.

This led to the Japanese looking for returns outside Japan. Some housewife traders started staying up at night to trade in the European and the North American financial markets. They borrowed money in yen at very low interest rates, converted it into foreign currencies and invested in bonds and other fixed-income instruments giving higher rates of returns than what was available in Japan.

Over a period of time, these housewives came to be known as Mrs Watanabes and, at their peak, accounted for around 30 percent of the foreign exchange market in Tokyo, writes Satyajit Das in Extreme Money.

The trading strategy of the Mrs Watanabes came to be known as the yen-carry trade and was soon being adopted by some of the biggest financial institutions in the world. A lot of the money that came into the United States during the dot-com bubble came through the yen-carry trade.

It was called the carry trade because investors made the carry, that is, the difference between the returns they made on their investment (in bonds, or even in stocks, for that matter) and the interest they paid on their borrowings in yen.

The strategy worked as long as the yen did not appreciate against other currencies, primarily the US dollar. Let’s try and understand this in some detail. In January 1995, one dollar was worth around 100 yen. At this point of time one Mrs Watanabe decided to invest one million yen in a dollar-denominated asset paying a fixed interest rate of 5 percent per year.

She borrowed this money in yen at the rate of 1 percent per year. The first thing she needed to do was to convert her yen into dollars. At $1 = 100 yen, she got $10,000 for her million yen, assuming for the ease of calculating that there was no costs of conversion.

This was invested at an interest rate of 5%. At the end of one year, in January 1996, $10,000 had grown to $10,500. Mrs Watanabe decided to convert this money back into yen. At that point, one dollar was worth 106 yen.

She got around 1.11 million yen ($10,500 × 106) or a return of 11 percent. She also needed to pay the interest of 1 percent on the borrowed money. Hence, her overall return was 10 percent. Her 5 percent return in dollar terms had been converted into a 10 percent return in yen terms because the yen had lost value against the dollar.

But let’s say that instead of depreciating against the dollar, as the yen actually did, it instead appreciated. Let’s further assume that in January 1996 one dollar was worth 95.5 yen. At this rate, the $10,500 that Mrs Watanabe got at the end of the year would have been worth 1 million yen ($10,500 × 95.5) when converted back into yen.

Hence, Mrs Watanabe would have ended up with the same amount that she had started with. This would have meant an overall loss, given that she had to pay an interest of 1 percent on the money she had borrowed in yen.

The point is that the return on the carry trade starts to go down when the currency in which the money has been borrowed, starts to appreciate. Since its beginnings in the mid-1990s, the yen carry trade worked in most years up to mid-2007. In June 2007, one dollar was worth 122.6 yen on an average. After this, the value of the yen against the dollar started to go up over the next few years.

With the yen expected to depreciate further against the dollar, it will lead to big institutional investors increasing their yen carry trades in the days to come. This will mean money will be borrowed in yen, and invested in financial markets all over the world.

Some of this money will find its way into the stock and the bond market in India. Moral of the story: The easy money rally is set to continue. The only question is till when?

Stay tuned!

The article originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com on Nov 19, 2014