George Soros has got some of the biggest macro calls right over the years. How does he do it? If you were to get around to reading all the books that Soros has written over the years, you will come to realise that he follows something known as the theory of reflexivity to get in and out of financial markets.

Nevertheless, his son Robert, offers another explanation for his success in Michael Kaufman’s Soros: The Life and Times of a Messianic Billionaire. As Robert puts it “My father will sit down and give you theories to explain why he does this or that. But I remember seeing it as a kid and thinking, Jesus Christ, at least half of this is bullshit, I mean, you know the reason he changes his position in the market or whatever is because his back starts killing him. It has nothing to do with reason. He literally goes into a spasm, and it’s his early warning sign.”

Soros himself has had his doubts about how he makes money. As he writes in The New Paradigm for Financial Markets – The Credit Crisis of 2008 and What It Means: “To what extent my financial success was due to my philosophy is a moot question because the salient feature of my theory is that it does not yield any firm predictions. Running a hedge fund involves the constant exercise of judgement in a risky environment, and that can be very stressful. I used to suffer from backaches and other psychosomatic ailments, and I received as many useful signals from my backaches as from my theory. Nevertheless, I attributed great importance to my philosophy and particularly my theory of reflexivity.”

And from the looks of it, seems like George Soros has had a few backaches of late. This time his worries are coming from China. Speaking at an economic forum in Sri Lanka, Soros recently said: “When I look at the financial markets there is a serious challenge which reminds me of the crisis we had in 2008…Unfortunately China has a major adjustment problem and it has a lot of choices and it can actually transfer to the rest of the world its own problems by devaluing its currency and that is what China is doing.”

Over the years, the Chinese yuan has been largely pegged against the American dollar. The People’s Bank of China, the Chinese central bank, has ensured that the value of the yuan has fluctuated in a fixed range around the dollar. This has been primarily done in order to take away the currency risk that the Chinese exporters may have otherwise faced.

In a world where so many things have changed in the aftermath of the financial crisis which started in September 2008, the value of the Chinese yuan against the dollar has been one of the few constants.

Over the last few months, the value of the Chinese yuan against the dollar has gradually been allowed to fall. In August 2015, the People’s Bank of China pushed the value of the dollar against the yuan, from 6.2 to around 6.37. In November 2015, one dollar was worth around 6.31 yuan. By the end of the year, one dollar was worth 6.48 yuan, with the yuan gradually depreciating against the dollar.

In the new year, the yuan has depreciated further against the dollar and one dollar is now worth around 6.58 yuan. So what is happening here? It is first important to understand how the People’s Bank of China has over the years maintained the value of the yuan against the dollar.

When Chinese exporters bring back dollars to China or when investors want to bring dollars into China, the Chinese central bank buys these dollars. They buy these dollars by selling yuan. This ensures that at any given point of time there is no scarcity of yuan and there are enough yuan in the market, in order to ensure that the value of the yuan is largely fixed against the dollar.

Where does the People’s Bank get the yuan from? It can simply create them out of thin air, by printing them or creating them digitally.

The situation has reversed in the recent past. Money is now leaving China. Hence, the total amount of dollars leaving China is now higher than the dollars entering it. And this has created a problem for the Chinese central bank. Between July and September 2015, the net capital outflows reached $221 billion. “[This] occurred for the sixth straight quarter and reached a new record of $221 billion,” wrote Jason Daw and Wei Yao of Societe Generale in a recent research note.

The fact that more dollars are now leaving China than entering it, changes the entire situation. When investors and others, decide to take their money out of China, what do they do? They sell their yuan and buy dollars. This pushes up the demand for dollars. In a normal foreign exchange market this would mean that the dollar would appreciate against the yuan, and the yuan would depreciate against the dollar.

But remember that the Chinese foreign exchange market is rigged. The People’s Bank of China likes to maintain a steady value of the yuan against the dollar. What does the Chinese central bank do when more dollars are leaving China? In order to ensure that there is no scarcity of dollars in the market, it buys yuan and sells dollars. This is exactly the opposite what it has been doing all these years, when more dollars where entering China than leaving it.

The trouble is that China cannot create dollars out of thin air, only the Federal Reserve of the United States can do that. China does not have an endless supply of dollars. The foreign exchange reserves of China as of December 2015 stood at $3.33 trillion. In December 2015, the foreign exchange reserves fell by $107.9 billion. They had fallen by $87.2 billion in November. In fact, between December 2014 and December 2015, the Chinese foreign exchange reserves have fallen by a huge $557 billion, in the process of defending the value of the yuan against the dollar.

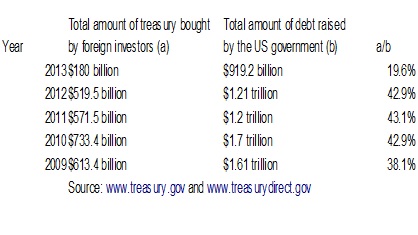

While, China has the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, it is worth asking what portion of these reserves are liquid? The Chinese central bank has invested these reserves in financial securities all over the world. As of October 2015, $1.25 trillion was invested in US government treasuries.

The question is how quickly can these investments be sold in order to defend the value of the yuan against the dollar? As economist Ajay Shah wrote in a recent column in the Business Standard: “For a few months, reserves have declined by a bit less than $100 billion a month. We may think that, with $3 trillion of reserves, the authorities can handle this scale of outflow for 30 months. Things might be a bit worse. Questions are being raised about the liquidity of the reserves portfolio. There are only a few global asset classes where the Chinese government can easily dispose of $100 billion of assets per month. A lot of the reserves portfolio might not be in these liquid asset classes.”

Given this, China does not have an endless supply of dollars and cannot constantly keep defending the yuan against the dollar. This explains why it has gone slow in defending the yuan against the dollar, in the recent past, and allowed its currency to depreciate against the dollar.

The question is why is all this worrying the world at large, Soros included? A weaker Chinese yuan will make Chinese exports more competitive. This will mean a headache for other export oriented economies like Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Germany, and so on. They will also have to push the value of their currencies down against the dollar. Hence, the global currency war which has been on a for a while, will continue. Further, a weaker yuan might lead to China exporting further deflation (lower prices) all over the world.

But what is more worrying is the fact that residents and non-residents are primarily the ones withdrawing their money out of China. The non-residents withdrew $82 billion during the period July to September 2015. The residents withdrew $67 billion, after having withdrawn $102 billion between March and June 2015.

When any economy is in trouble it is the locals who start to withdraw money first. This is clearly happening in China. And that has got the world worried. Also, China is a major consumer of commodities and any economic slowdown in China, will lead to a fall in commodity demand. This isn’t good news for many commodity exporting countries in particular and global economic growth in general.

The column originally appeared on the Vivek Kaul’s Diary on January 13, 2016