Link to Video 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DMY_ZRLqoaI&feature=youtu.be

Link to Video 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPNSg41dWkI&feature=youtu.be

A lot of questions have been raised about the validity of the economic growth number put out by the ministry of statistics and programme implementation earlier this month. The ministry expects the gross domestic product(GDP) growth during this financial year to be at 7.4%. The number was based on a new GDP series. Before this, the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) had forecast a GDP growth of 5.5%.

Until now, no reasonable explanations of this sudden jump in economic growth have been provided. The trouble, as I have mentioned on earlier occasions, is that, the high frequency data that has been coming out doesn’t seem to suggest that the economy has any chance of growing at 7.4%.

In fact, some high frequency data that has come out over the last few days, continues to suggest that it is unlikely that the economic growth during this financial year will be at 7.4%.

Take the case of corporate profit and sales. A recent news report in the Business Standard points out that “aggregate net profit of 2,941 companies” declined by 16.9%. The sales growth also has been the weakest in at least 12 quarters, the report points out. Falling profits and slowing sales clearly show weak consumer demand.

This has also led to the tax collection targets of the government going awry. For the first ten months of the financial year between April 2014 and January 2015, the total amount of indirect tax(service tax, central excise duty, customs duty) collected went up by 7.4%, in comparison to the last financial year.

The budget had assumed a 20.3% jump in indirect tax collections. And that hasn’t happened. In fact only 68.6% of the annual indirect tax target has been collected in the first ten months of the financial year. It seems highly unlikely that the government will be able to meet the indirect tax target that it had set for itself at the time it presented the budget in July 2014.

Things are a little better on the direct taxes front. The growth in direct taxes was expected to be at 15.7% during the course of the year. The actual growth during the first ten months of this financial year has been at 11.4%. Hence, the gap between the expected growth and the actual growth is not as huge as it is in the case of indirect taxes. In fact, Rs 5,78,715 crore or 78.6% of the annual target has been collected during the first ten months of this financial year.

Direct taxes are back ended(i.e. a large part gets paid during the last three months of the financial year). In a report titled Will the Government Meet the Fiscal Deficit Target for F2015? analysts Chetan Ahya and Upasana Chachra of Morgan Stanley point out that “tax collection picks up seasonally toward the end of the fiscal year, with direct tax collection between December and March at 51.4% of total (five-year average).”

Given this, the gap between expected collections and the actual collections will not be huge, by the time this financial year ends. But indirect taxes will continue to be a worry.

There is other high frequency data which clearly suggests that all is not well with the Indian economy. Loans given by banks are one such data point. Latest data released by the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) suggests that bank loans have grown by 10.7% over the last one year (as on January 23, 2015). In comparison, they had grown by 14.4% a year earlier. Interestingly, bank loans have grown by just 6.7% during this financial year.

In fact, things get more interesting if we look at the sectoral deployment of credit data released by the RBI. This data among other things gives a breakdown of the total amount of bank lending that has happened to different sectors of the economy.

The lending to industry has grown by 6.8% during the last one year (as on December 26, 2014). During the same period a year ago, the lending had grown by 14.1%. A slowdown in bank lending is another clear indication that all is not well with Indian businesses as well as the economy.

A major reason for this slowdown in lending is the fact that public sector banks are still facing the problem of bad loans. As Amay Hattangadi and Swanand Kelkar of Morgan Stanley write in their latest Connecting the Dots newsletter titled Putting Serendipity to Work: “State-owned banks that comprise over 75% of the banking system’s outstanding loans are constrained in their ability to lend. Neither has the formation of bad assets ebbed, as is being evidenced in their latest quarterly reports nor have they been able to raise adequate capital to accelerate lending.”

The monthly wholesale price index (WPI) inflation data also points in the same direction. For the month of January 2015, the WPI inflation was at (-)0.39% versus 0.11% in December 2014. Manufactured products which form 64.97% of the index declined by 0.3%. What this tells us is that manufactured products inflation has more or less collapsed. A major reason for the same lies in the fact that people are going slow on buying goods.

Despite falling inflation, people still haven’t come out with their shopping bags. When consumers are going slow on purchasing goods, it makes no sense for businesses to manufacture them. This also tells us that businesses have lost their pricing power, given that consumers are not shopping as much as the manufacturers can produce.

If all this wasn’t good enough, exports have been growing at a minuscule pace as well. The total exports for the period April 2014 to January 2015 stood at $265.04 billion. Between Apirl 2013 and January 2014 the exports had stood at $258.72 billion. This means a growth of 2.44% in dollar terms, which is nothing great. In fact, during January 2015, exports stood at $23.88 billion down 11.2% in comparison to January 2014.

Car sales, another good indicator of economic activity, also remain subdued. They grew by 3% in January. The Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) expects sales growth to be subded during this financial year at 3-5%.

What all this clearly tells us is that 7.4% GDP growth is just a number. It is clearly not happening at the ground level.

The column originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com as a part of The Daily Reckoning, on Feb 19, 2015

The inspiration to write this piece came from a news report which appeared in the Mumbai edition of the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) a few days back. Before I get into that I would like to recount something, which I am really not proud of.

One of my bigger mistakes(I am still debating if it was my biggest mistake) in life was to do an MBA (actually a post graduate diploma in management(PGDM), but calling it an MBA is a simpler way to talk about it). By the time three-fourths of the course got over, I came to the conclusion that I was wasting my time and this is not what I wanted to do with my life. Nevertheless, it was too late to pull out. I completed the course, got the diploma and a job, and then quit my job, to try and figure out what to do with my life.

At this point of time I was in Delhi. My days used to be spent either watching new Hindi films or reading books at the four storied Crossword Book Shop at South Extension, which has since shut-down. To be honest I was never more happy with my life. The only problem was I had no money. And I did not want to ask my father for any more money, given that he had already spent quite a lot on my MBA.

But I had just become too addicted to books and movies by then. I was reading one book on an average per day and also buying them to ensure that Crossword does not throw me out. The money to buy books and watch movies came from my student credit card. Those were the days(I guess it still happens) where if you managed to get through a good business school, one of the first things you would end up with is a credit card from a foreign bank. The banks wanted to catch the future moneybags, young.

I knew that this wouldn’t last forever. Nevertheless, I continued using my credit card, having made up my mind to default on the outstanding payment. My confidence came from the fact that the residential address that I had given to the bank had changed because my parents had moved to a different city. Hence, the chances of collection agents landing up were slim.

This personal bubble did not last forever. And soon a lawyer representing the bank sent a legal notice threatening to initiate criminal or civil proceedings (he did not specify which) to my old residential address, unless a certain amount of money was paid to settle the debt I had accumulated.

A concerned neighbour decided to accept the notice and call up my father and inform him about it. My father then decided to settle the amount with the lawyer and that was where it ended.

The one result of this entire experience has been that I have never had a credit card. The only time I applied for a credit card from a new generation private sector bank, my application was rejected, given that my name would have been on the defaulter databases that banks now use. Also, I haven’t gotten around to taking any loans from banks either. In that sense, I have almost no credit history other than the credit card default.

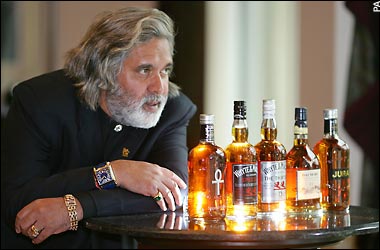

Now you must be wondering why have I been going on and on about my credit card default. I just remembered the entire experience after reading a news report in the Daily News and Analysis about Vijay Mallya, one of the biggest defaulters of this day and age.

This news report suggests that of the Rs 7,000 crore that various banks had lent to Kingfisher Airlines, they can now recover only Rs 6 crore. As the report points out: “The State Bank of India (SBI), the major lender to Mallya’s airline, till now has managed to recover only Rs 155 crore out of the Rs 1,623 crore due from it. dna has learnt from official SBI sources that the value of Kingfisher Airlines pledged to the bank has now plummeted from Rs 4,000 crore to Rs 6 crore! SBI is unable to find a single buyer for the ‘Kingfisher’ trademarks.”

Some of the other assets that the company offered as a collateral to banks are now stuck in litigation. This includes the Kingfisher House in Andheri, Mumbai and the Kingfisher Villa in Goa. As a recent report in The Financial Express said: “Bankers’ attempts to take possession of Kingfisher Villa in Goa have been thwarted by United Spirits (USL), which claims it has been a tenant since 2005 and, therefore, has the first right to buy the property.”

The banks waited for too long in the hope that Mallya will repay. And now they are not in a position to recover any of the money that they had lent. As Raghuram Rajan, governor of the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) had said in a speech in November 2014: “The longer the delay in dealing with the borrower’s financial distress, the greater the loss in enterprise value.”

Further, banks gave loans to Mallya even when their board members protested. As the DNA reports: “CBI sources reveal that IDBI had extended loans to Kingfisher despite being warned by some board members not to do so.”

Mallya exemplifies in the best possible manner what has gone wrong with the Indian banking system. Public sector banks have lent a lot of money to crony capitalists who are now no longer in a position to return that money. But they are in a position to hire the best possible lawyers to ensure that when banks move in to recover the money they had lent, the process gets endlessly delayed in the courts.

This has led banks to go after small and medium enterprises which are unable to repay their loans, with a vengeance. These enterprises are not in a position to hire expensive lawyers ike Mallya is. As Rajan put it in his speech: “[The] full force is felt by the small entrepreneur who does not have the wherewithal to hire expensive lawyers or move the courts, even while the influential promoter once again escapes its rigour. The small entrepreneur’s assets are repossessed quickly and sold, extinguishing many a promising business that could do with a little support from bankers.”

The case of banks going after small and medium enterprises is similar to my case. When it comes to recovering their loans, the banks go with full force behind people who are not in a position to hire expensive lawyers and do not have the wherewithal to get stuck with the legal system. The bigger defaulters they just let go. As George Orwell wrote in the Animal Farm: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

The column originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com as a part of The Daily Reckoning on Feb 18, 2015

Vivek Kaul

The Economic Survey for the last financial year states: “Data shows that the first claim upon the savings of households is physical assets such as gold and real estate.”

That Indians love their ‘real estate’ would be like stating the obvious. But sometimes it is necessary to state the obvious as well. Why? That will soon become clear.

AkhileshTilotia, a thematic research analyst with the institutional equities arm of the Kotak Mahindra Group, makes a very interesting point in his new book The Making of India—Gamechanging Transitions. As he writes: “Thanks to its love for real estate investments, India is in a curious position of having more houses than it has households.”

This becomes clear from the Census 2011 data. “India’s households increased by 60 million to 247 million from 187 million between 2001-2011. Reflecting India’s higher ‘physical’ savings, the number of houses went up by 81 million to 331 million from 250 million. The urban increases is telling: 38 million new houses for 24 million new households,” writes Tilotia.

So what is happening here? One explanation for the number of houses rising faster than the number of households may lie in the fact that houses are being bought as investment and not to be lived in.

What this means is that many Indians own more than one house and then there are many more who do not own any, because prices are way beyond what they can afford. Further, given our penchant for owning real estate, a lot of real estate is being built sheerly from the point of view of fulfilling investment demand.

The Caravan magazine in a 2011 article, when real estate investment was at its peak, quoted Gautam Bhan, a consultant with the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, to make this point: “This economy is being built solely on speculation…These properties are being built solely for investment cycles. Why else would you build halfway to Agra? If you have ten businessmen who occasionally want to get rid of black money, you’ll have an apartment building. These flats will be bought and resold and bought and resold. Nobody even needs to live there.”

This is the best possible explanation for why the number of houses has gone up at a much faster pace than the number of households.

Further, those who have black money to hide, don’t bother much about the location of where houses are being built. And that explains why houses even miles away from India’s biggest cities are so expensive.

So what is the way out of this mess? How can houses be built and sold at prices so that people can buy them to live in them? As I have mentioned more than a few times in the past, the government needs to actively go after the black money hidden in physical assets like gold and real estate. There is no point in trying to actively pursue all the black money that has left the country and not do anything about all the black money lying in the country.

A crackdown on black money will lead to better tax compliance, meaning more taxes for the government. Further, it will also bring down the amount of black money that goes into black estate. This is easier said than done and will need solid political will for many years, if it has to be pursued seriously.

Further, it is high time that agricultural income be brought under the tax net. There is no reason that rich farmers should not be paying income tax. In fact, in cities like Shimla, Chandigarh and even the National Capital Region, all the untaxed agricultural income chasing real estate has also been responsible for driving up home prices, among other things.

Ensuring affordable housing becomes available at a large scale level should be a major priority for the Narendra Modi government. As the Economic Survey points out: “Nearly 30 per cent of the country’s population lives in cities and urban areas and this figure is projected to reach 50 per cent in 2030.” If affordable housing does not become the order of the day slums will become as common place in other cities, as they are currently in Mumbai. And that is not a happy thought to look forward to.

Also, as Tilotia points out in his book, “more than three-fourths of urban residents live cheek by jowl in cramped spaces.” This basically happens because of two reasons. The first reason is the low FSI ratio which has made land very expensive. The second reason is “the inability to commute cheaply and quickly, which means that people have to congregate in and around areas where they can find economic activity and public infrastructure.”

If affordable housing has to take off, all this needs to be set right.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on Feb 18, 2015

Over the last one month some speaking engagements have taken me out of Mumbai. While travelling, I have spoken to people from different strata of society—from drivers to waiters to economists to businessmen to investment bankers.

There seems to be a great belief among people that the Narendra Modi government is likely to make some difference in the life of an ordinary Indian over the next few years. I maybe merely stating the obvious here, but it will soon become clear why I am doing that.

The marketing and communication that has accompanied Narendra Modi’s ascent to become the prime minister of India has been brilliant. Also, for the first time the message of economic development has been sold to people. The belief that this marketing and communication has created has stayed even after Modi has been in power for close to nine months.

But along the way some bad marketing has also crept in. Take the case of various leaders of the Bhartiya Janata Party(BJP) even taking the credit for bringing down oil prices. As a recent editorial in the Business Standard pointed out: “The president of the ruling party, Amit Shah, for example, repeatedly took credit on the campaign trail for lower prices, as did the Union home minister, Rajnath Singh. Even the prime minister has mentioned lower fuel prices, though he has specified that it is because of his “luck”.”

In my conversations over the last one month I have realized that many people particularly in the lower strata, seem to believe, that the Modi government has brought down petrol and diesel prices. This is an impact of the bad marketing on part of the BJP. When I put this to a friend who works for a foreign brokerage house, he replied: “you market what sells”. “And if people are believing in it, that means it’s selling.”

Nevertheless that is just one side of the picture. The price of the Indian basket of crude oil on May 26, 2014, the day the Modi government was sworn in, was $ 108.05 per barrel. It fell by around 60% to $43.36 per barrel on January 14, 2015. This was the period when the BJP leaders were busy claiming credit for the fall in oil price, whenever an opportunity presented itself.

What they did not tell people was that only a very small part of this fall in price was passed on to the end consumer through a cut in the price of petrol and diesel. Take the case of price of petrol in Mumbai—the price fell by only 17.05% between end May 2014 and mid January 2015. The price of diesel during the same period fell by around 14.9% in Mumbai.

The primary reason for this discrepancy has been that the government tax collections have not been up to the mark. Take the case of indirect taxes(service tax, customs duty and central excise duty). For the first ten months of the financial year between April 2014 and January 2015, the total amount of indirect taxes collected went up by 7.4%, in comparison to the last financial year. The budget had assumed a 20.3% jump in indirect tax collections. And that hasn’t happened. A little under one third of the indirect tax target still remains to be collected.

This slow growth in indirect tax collections has forced the government to increase the excise duty on petrol and diesel multiple times since October 2014. In the process it hasn’t passed on the total fall in the price of oil to the end consumer.

There is nothing wrong here, a government needs to constantly look at its finances and make decisions accordingly. The trouble is that since mid January oil prices have started going up again. Between January 14 and February 13, 2015, the price of Indian basket of crude oil has gone up by 34.7% to $ 58.43 per barrel.

This increase in price has forced the oil marketing companies to increase the retail price of petro and diesel by 1.45% and 1.3% respectively, since February 16. If the oil price keeps going up, then the oil marketing companies will have to keep increasing the price of petrol and diesel. And this will put the BJP which had been claiming that the Modi government brought down the price of petrol and diesel, in a tough spot.

Those who believed that the government was responsible for bringing down the price of petrol and diesel, will now ask—if the government can bring down the price of petrol and diesel, it can also ensure that their prices do not go up.

If this belief starts to gain hold, then the government can be forced to hold steady the price of petrol and diesel, and in turn compensate the oil marketing companies for the under-recoveries they suffer in the process. This will lead to a lot of other problems, most of which the country has already suffered during the ten years of Congress led UPA rule.

Indian politicians have not marketed economic reforms ( allowing listed companies to sell a commodity at its right price is also economic reform) at all to the citizens of this country. In fact, the spin that they have given to economic reforms has hurt this country.

Instead of claiming credit and saying that the Modi government brought down prices of petrol and diesel, the BJP politicians should have been telling the country why it is important to sell things at their right price. As Mihir S. Sharma writes in his book Restart—The Last Chance for the Indian Economy: “India has paid for politicians unable to talk openly about how economic reform is not just necessary, but beneficial, and not just beneficial, but right.”

Such communication isn’t very easy to dumb down, but that does not mean it cannot be done. It’s just that nobody has bothered to try till now. What makes the process even more difficult is the fact that every time a ruling party loses a state election, it gets blamed on economic reforms or the fact that the other side promised freebies, which the ruling party did not.

Take the case of the recent elections in Delhi, where the BJP was wiped out. Political pundits took no time in saying that the BJP lost because the Aam Aadmi Party promised freebies. As Sharma writes: “From [Narsimha] Rao all politicians have inherited the ability to attribute every electoral reversal to economic reforms.”

What we have seen till now is economic reforms by stealth. What is essentially needed is some proper communication on behalf of the government, where economic reforms can be explained in a simple way to the common man. That is the kind of marketing that is needed. And it would be great if the Modi government can get around to doing that.

The column originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com as a part of The Daily Reckoning, on Feb 17, 2015