Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, has survived in the political and bureaucratic circles of Delhi for nearly three decades now. Given this it is safe to say that he has well honed survival instincts, which tell him when the tide is turning.

And when the tide is turning, it makes sense to change direction and flow with the tide rather than risk drowning. This is precisely what Ahluwalia did yesterday. As he remarked “As the country becomes richer and the per capita income goes up, there is need to redefine the poverty line. The latest numbers that planning commission have released, based on the Tendulkar Committee report, are absolutely rock-bottom numbers and gives us the number of poor who are actually the weakest group and therefore, should be the priority of the government.”

This is like a father disowning his son. The statement came after the latest set of poverty numbers were slammed by leaders across the political spectrum. The Congress party tried defending the numbers initially, but then did a volte face and has since come out all guns blazing against the current poverty line, which decides who is poor and who is not. The opposition parties from the left to the right have slammed the poverty line as well.

The current poverty line was decided by the report of the expert group to review methodology for estimation of poverty. The report was released in November 2009 (It is better known as the Tendulkar committee report). The report set the “the estimates of poverty…on private household consumer expenditure of Indian households.” The committee arrived at that numbers taking into account the expenditure on food, clothing, footwear, durables, education and health.

This line was an improvement on the earlier poverty line which only only took into account the expenditure required to consume an identified number of food calories. For rural India this number was 2,400 calories. For urban India this number was at 2,100 calories. Anyone consuming less than this was deemed to be poor.

The Tendulkar Committee changed this. “The expert group has also taken a conscious decision to move away from anchoring the poverty lines to a calorie intake norm,” its report said.

And there were reasons for doing so. There has been a long term trend of declining calorie consumption in both rural and urban areas. For urban India the consumption was at 1776 calories per day per person. And for rural India it stood at 1999 calories per day per person, observed the Tendulkar committee. In fact the calories being consumed in urban as well as rural area were higher than the revised calorie intake norm of 1770 calories per person per day specified by the Food and Agriculture Organisation(FAO) for India.

This specific point has come in for a lot of criticism, specially from those who lean towards the left. In a column in The Hindu, Utsa Patnaik of the Jawaharlal Nehru University writes “All official claims of low poverty level and poverty decline are quite spurious, solely the result of mistaken method. In reality, poverty is high and rising. By 2009-10, after meeting all essential non-food expenses (manufactured necessities, utilities, rent, transport, health, education), 75.5 per cent of rural persons could not consume enough food to give 2200 calories per day, while 73 per cent of all urban persons could not access 2100 calories per day. The comparable percentages for 2004-5 were 69.5 rural and 64.5 urban, so there has been a substantial poverty rise.”

But what this statement does not take into account is the fact that there is a long term trend of declining calorie consumption in both urban as well as rural India. This is something that Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya discuss in great detail in their book India’s Tryst with Destiny – Debunking Myths that Undermine Progress and Addressing New Challenges. “The long-term trend is one of declining calorie consumption in both rural and urban areas though the trend is steadier in rural rather than urban areas.”

And there are reasons for the declining trend in calorie consumption. As Bhagwati and Panagariya point out “For example, greater mechanization in agriculture, improved means of transportation and a shift away from physically challenging jobs may have reduced the need for physical activity. Likewise, better absorption of of food made possible by improved epidemiological environment (better child and adult health and better access to safe drinking water) may have lowered the needed calorie consumption to produce a given amount of energy.”

So saying that because the calorie consumption has gone down, hence India is poorer, is really not correct. Left leaning activists and economists have constantly pointed out that the decline in calorie consumption is an indication of increased hunger and malnutrition.

But there is enough evidence to prove the contrary. “When directly asked whether they had enough to eat everyday of the year, successive rounds of expenditure surveys of the NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) show increasing proportions of the respondents answering in the affirmative. In the 1983 expenditures survey, only 81.1 per cent of the respondents in the rural areas and 93.3 per cent in the urban areas stated that they had enough food everyday of the year. But by 2004-05, these percentages had risen to 97.4 per cent and 99.4 per cent,” write Bhagwati and Panagariya.

A March 2013 report in The Mint also makes a similar point. “A February report of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) shows the proportion of people not getting two square meals a day dropped to about 1% in rural India and 0.4% in urban India in 2009-10.”

The malnutrition argument also doesn’t quite hold either. Interestingly, Bhagwati and Panagariya, cite research carried out by Angus Deaton and Jean Drèze. Drèze has been a long time collaborator of Amartya Sen. “Deaton and Drèze also analyse the data on the heights of different cohorts of men and women collected by the second and third rounds of National Family Health Survey and conclude that later-born adult men and women are taller. They calculate that the rate of increase of height is 0.56 centimetre per decade for men and 0.18 centimetre per decade for women. Thus, even if India continues to do poorly in international comparisons, all trends point to improving and not worsening adult nutrition,” write Bhagwati and Panagariya.

So there is enough evidence to suggest that calorie intake has been going down and it hasn’t led to greater malnutrition and hunger. Hence, criticism of the Tendulkar committee report on this point, doesn’t really hold.

Also it is important to remember that the Tendulkar committee made the poverty line multidimensional, by considering several other expenditures other than just food. An immediate impact of this was that the poverty ratio for 2004-05, went up from 27.5% to 37.2% of the total population. From that level the poverty ratio has come down to 21.9% in 2011-12.

But that doesn’t mean that there are no problems with the poverty line set by the Tendulkar committee. The committee set the consumption expenditure in order to avoid poverty at Rs 816 per person per month in the rural areas and Rs 1000 per person per month in the urban areas. For a family of five people, this amounts to Rs 4,080 per month in rural areas and Rs 5000 per month in urban areas.

This of course translates into an expenditure of around Rs 27 per day for rural areas and Rs 33 per day for urban areas, two numbers that have caused a lot of outrage over the last one week. There is no denying that the numbers are very low. In fact, within this cut off expenditure, one of the assumptions is a healthcare expenditure of less than Re 1 per day. As Harsh Mander, a former member of the National Advisory Council, put it in The Mint, this was “barely enough to buy an aspirin”.

Despite these points, the Tendulkar Committee poverty line is in line with the definition of poverty used by 189 members of the United Nations to set the first of eight Millennium Development Goals of halving global poverty between 1990 and 2015.

As T N Ninan wrote in the Business Standard “The definition of poverty used to set this goal is $1.25 per day. That would be about Rs 75 per day in a straight conversion to rupees at current exchange rates, but works out to about Rs 30 when you take purchasing power parity into account, as you are supposed to. As it happens, the Tendulkar line for rural areas in 2011-12 was Rs 27, and in urban areas Rs 33. So any criticism of the Tendulkar definition of extreme poverty runs smack into what is the internationally accepted definition.”

Also, the Congress party as well as the opposition parties which are criticising this formula now, could have first done so more than three years back in late 2009, when the report was first made public. But they chose to be quiet then.

Despite the problems that it has, what the Tendulkar committee poverty line measures is extreme poverty or what Ahluwalia refers to as “the weakest group” and which “should be the priority of the government”.

Raising this line would have its own set of problems, which this writer has pointed out in the past.

“For example, suppose we raise the rural poverty line to Rs 80 and the urban one to Rs 100 at 2009-10 prices. What would these lines imply?” ask Bhagwati and Panagariya.

This would designate 95% of the rural population and 85% of the urban population to be poor. And that does not help anybody, except those who repeatedly like to shout that “India is poor”. Yes, we all know India is a poor country, but then what’s new about that?

Increasing the cut off for poverty, would mean that scarce government resources will be spread over a larger set of population. As Bhagwati and Panagariya point out “With tax revenues still relatively modest, significant redistribution in favour of the destitute requires limiting such redistributions to the bottom 40 percent or so of the population. Spreading them thinly over a vast population will give too little to the destitute to make a major dent in poverty.”

So the more poor will lose out to the less poor.

Given this, it makes sense for India to have at least two poverty lines, one to tackle extreme poverty and one to measure ‘real’ poverty. The World Bank uses two poverty lines. One is the extreme poverty line, which is set at an expenditure of $1.25 per day. And another is a moderate poverty line which is set at $2 per day.

Economist Devinder Sharma in a column in the Rajasthan Patrika writes about the South African experience. South Africa has three poverty lines. The first is the food line with a cut off expenditure of Rs 1841 per month. Then comes the middle poverty line at Rs 2,445. And the upper poverty line at Rs 3484.

India needs something along these lines. Dumping the Tendulkar committee poverty line does not serve much purpose. It should continue to help target the “extreme poor”, whose number has gone down over the years.

But when it comes to measuring real “poverty” India does need a higher cut off. World bank’s moderate poverty line of $2 per day, adjusted for purchasing power parity, would be a good bet to start with. Of course the risk here is that the politicians can make the upper poverty line, the real poverty line, and start distributing “freebies” on the basis of that, making it a fiscally disastrous proposition for the government. Remember, the food security scheme?

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 30, 2013 under a different headline

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Month: July 2013

Needed: A new poverty line which shows 67% of the country is poor

Vivek Kaul

The Congress party after claiming that its social policies over the last nine years had helped bring down poverty in the country, now seems to have done a volte face.

Data released by the Planning Commission on July 22, 2013, suggested that poverty in India had declined from 37.2% in 2004-05 to 21.9% by 2011-12. Several spokespersons of the Congress party led United Progressive Alliance(UPA) were quick to claim credit, and attributed this to several social sector programmes that the party had launched during its tenure.

A poverty line separates the poor section of the population from the non poor section. Those below the poverty line are deemed to be poor and those who are above it are deemed to be not poor. And what exactly is a poverty line? As S Subramanian writes in The Poverty Line “A poverty line is identified in monetary units as the level of income or consumption expenditure required in order to avoid poverty.”

The consumption expenditure in order to avoid poverty is set at Rs 816 per person per month in the rural areas and Rs 1000 per person per month in the urban areas. For a family of five people, this amounts to Rs 4,080 per month in rural areas and Rs 5000 per month in urban areas.

These numbers were set by the report of the expert group to review methodology for estimation of poverty. The report was released in November 2009 (It is better known as the Tendulkar committee report).

The committee arrived at that numbers taking into account the expenditure on food, clothing, footwear, durables, education and health. “Actual private expenditures reported by households near the new poverty lines on these items were found to be adequate at the all‐India level in both the rural and the urban areas and for most of the states,” the report said.

Interestingly, the Tendulkar committee poverty line was an improvement on the earlier poverty line which only took into account the expenditure required to consume an identified number of food calories. For rural India this number was 2,400 calories. For urban India this number was at 2,100 calories. Anyone consuming less than this was deemed to be poor.

The Tendulkar committee made the poverty line multidimensional, by considering several other expenditures other than just food. An immediate impact of this was that the poverty ratio for 2004-05, went up from 27.5% to 37.2% of the total population. From that level the poverty ratio has come down to 21.9% in 2011-12.

So prima facie this sounds good. The trouble crops up when Rs 816/Rs 1000 per month is converted into expenditure per day. Assuming 30 days in a month, this expenditure comes to Rs 27.5 per day for the rural areas and Rs 33.33 for urban areas. Hence, anyone whose expenditure per day is less than these amounts is categorised as poor.

Having already linked the reduction in poverty to the social sector schemes launched by the government, the Congress spokespersons had to defend the Rs 27-33 per day expenditure cut off for poverty.

“Even today in Mumbai city, I can have a full meal at Rs 12. No no not vada paav. So much of rice, dal sambhar and with that some vegetables are also mixed ,” film star turned politician Raj Babbar told reporters.

Rasheed Masood, a Congress leader from Delhi, went a step further and said “You can eat a meal in Delhi in Rs 5 I don’t know about Mumbai. You can get a meal for Rs 5 near Jama Masjid.”

Farooq Abdullah of the National Congress, a constituent of the UPA, said that even Re 1 was enough to satisfy hunger. “If you want, you can fill your stomach for Re 1 or Rs 100, depending on what you want to eat,” Abdullah said.

Of course these gentlemen were trying to justify the unjustifiable. Rs 27-33 per day expenditure as a cut off for poverty is too low. But the argument is not as simple as that. As we saw the current poverty line is an improvement on the earlier line. There has been a lot of criticism of the late Suresh Tendulkar, who headed the committee that redefined the poverty line. As T N Ninan wrote in the Business Standard “The late Suresh Tendulkar, who redefined the line some years ago, has come in for unfair criticism – because he actually raised the poverty line substantially. The result was that what was 27 per cent poor in 2004-05 under the old definition became 37 per cent using Tendulkar’s definition.”

The simple solution it seems is to increase the poverty line. But as this writer explained earlier, increasing the poverty line has its own serious repercussions.

Also, even if we were to increase the poverty line, the percentage of decline of in poverty will remain the same. As Pronab Sen, chairman of the National Statistical Commission, told Outlook “even if we double the norm from Rs 33 for urban poor and Rs 28 for rural poor, the percentage of people below poverty line may double but the percentage of decline in poverty will remain roughly the same.”

Economist Bhaskar Dutta wrote something along similar lines in a column in The Indian Express. “the dramatic reduction in poverty according to the Planning Commission estimate also guarantees that there would be a sizeable reduction even if the poverty line were set a higher level.”

And this fall in poverty, irrespective of where we set the poverty line at, has been substantial. As Swaminathan Aiyar wrote in The Times of India “India has just reduced its number of poor from 407 million to 269 million, a fall of 138 million in seven years between 2004-05 and 2011-12 . This is faster than China’s poverty reduction rate at a comparable stage of development, though for a much shorter period.”

Instead of trying to make these slightly nuanced points the Congress party got stuck with justifying the poverty line cut off. The trouble was that it couldn’t go on and on about the “poverty has come down message”, simply because through the food security ordinance the party plans to distribute heavily subsided(almost free) rice and wheat to nearly 82 crore people or around 67% of the country’s population.

If the poverty has actually come down then the garibi hatao politics that the Congress party has been successfully peddling for nearly four decades, wouldn’t find any resonance any more. It would hit at the heart of the business model of the Congress party.

Hence, the party has done a quick volte face on the poverty line and is now vociferously criticising it. “If the Plan panel said those who live above Rs 5,000 a month are not at poverty line, obviously there is something wrong with the definition of poverty in this country. How can anybody live at Rs 5,000?” union minister Kapil Sibal asked at a public function.

The Congress general secretary, Digivijaya Singh, was also critical of the poverty line. “I have always failed to understand the Planning Commission criteria for fixing poverty line. It is too abstract can’t be same for all areas,” he tweeted.

Rajeev Shukla, Minister of State for Parliamentary Affairs, also joined his senior colleagues in criticising the poverty line. In fact, he went a step further and totally disowned it. “I want to demolish this myth that the poverty line has been fixed by the government. Government has not fixed any poverty line. This recommendation has been made by an expert panel headed by Mr. Tendulkar. This is a report of the Tendulkar Committee which has been put forward by the Planning Commission. Neither the Government has accepted it nor has it fixed it,” he said.

So, does Mr Shukla mean that the Planning Commission is different from the government and is not a part of the government? I guess some history is in order here. The website of the Planning Commission clearly points out that “The Planning Commission was set up by a Resolution of the Government of India in March 1950 in pursuance of declared objectives of the Government to promote a rapid rise in the standard of living of the people by efficient exploitation of the resources of the country, increasing production and offering opportunities to all for employment in the service of the community.”

Over and above this the Planning Commission is headed by the Prime Minister, who currently happens to be Manmohan Singh. So how can the Planning Commission be different from the government? Manmohan Singh as always has been made the scapegoat by the Congress party here as well.

Meanwhile, there is another committee at work with the brief to come up with a new better poverty line. This line will be needed to justify the massive food security scheme. If only 21.9% of India’s population is poor, then its difficult for the government to justify distributing heavily subsidised rice and wheat to nearly 67% of India’s population.

So what is needed is a new poverty line which shows that 67% of India’s population is actually poor. As Aiyar put it in his column “The government found it difficult to say this was good politics even if it was bad economics. Instead, it appointed the Rangarajan Committee to devise a higher poverty line.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 29, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

‘Adapt to India, don’t wait for it to catch up with your model’

Ravi Venkatesan is the former Chairman of Microsoft India and Cummins India. He is currently a director on the boards of Infosys and AB Volvo. Most recently he has authored Win in India, Win Everywhere – Conquering the Chaos (Harvard Business Review Press, Rs 895). In the book he makes a case for multi-national companies (MNCs) not to ignore India, despite the country being a VUCCA market (i.e. operating in an environment characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, corruption and ambiguity). In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

The first thing I felt after reading your book was that given the current scenario in our country, its a tad too optimistic….

The reality of the Indian economy is very grim. But in spite of that companies need to find a way to break through. India is one of those extraordinarily fortunate countries which has to do nothing to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). People are dying to come here. We just have to stop scaring them away. Unfortunately we have done a pretty good job of scaring them away to the point where they are really losing interest.

Why have only a few MNCs succeeded in India?

Because only a handful of them have taken the country seriously. It takes three things to succeed in a market like India. Number one is the mindset. Companies need to realise that India is strategically important. It may not have their act together now, but a country of billion people cannot be ignored without consequences. So lets take a long term view. Lets be a leader. That is the mindset needed.

The second thing you need is to get the leadership right. You need a stable leadership team you can trust. You empower them overtime to take most of the decisions. But very few companies have succeeded in doing that. For most of them it is a fast moving sales outfit with no imagination.

The third thing you have to get right is that you have to realise you have to adapt to the country rather than wait for the country to catch up to your business model.

In India the business model may never catch up with you….

Yes. So if you are Apple and you say listen I am going to wait till the distribution system is more efficient and more Indians can afford the iPhone as is. Fine yaar.

Meanwhile the Indians will buy a Samsung...

Yeah. They will buy a little Samsung. A little HTC. A little Nokia. And you are going to be wiped out. When you look at it, this doesn’t sound to be much. But it is an extraordinary one in a hundred who actually gets these three elements right.

So the mindset is very important?

Yes. The global headquarters might say oh my God if they come up with something it will cannibalise my rich product. Imagine an iPhone that is half the price and almost everything that an iPhone is. That would not be good news. It would mean cheapening the brand and destroying the profitability of the company because the Americans will ask why can’t I have that phone as well. And so usually companies decide that do nothing is a good strategy.

Can you give us an example of a company which came to India, tried establishing its business model which did not work and then adapted it with success…

Microsoft came to India with its arrogance and established a certain presence. Then Bill Gates woke up and he realised, hey listen we have a $100 million business and 1000 people in a country of a billion people. What is going on? This was 2003. So they hired me in all their wisdom, even though I did not know anything about IT.

What was one of the main issues facing the company? Back then the piracy rate was 75%. Bill said this is okay. We will get them using it, one day we will collect. Steve Ballmer said, time has come to collect. “You are the country head, you collect,” he told me.

What did you do?

I went around enforcement, ye wo kiya, par kuch nahi hua (did this and that, but nothing happened). Then one minister, who shall remained unnamed, called me, and spoke to me in Tamil, and said “listen, you seem like a good guy, but maybe a little stupid. So let me give you some advise. Copyright in India means right to copy. So you change your business model because India is not going to change for you guys.” So we changed our business model in 2006-07. We changed our pricing. We came up with local language versions. Changed distribution and took the piracy rate down from 75% to 64% and saw dramatic growth.

You cut prices dramatically…

Office used to be $300. We came up with Office Home and Student which is $60. We came up with a version of Office for government schools which was $2. So if somebody said what is the price of Office in India? The answer was I don’t know. It’s free if you are an NGO. It’s two dollars if you are a school, and its $300 if you are Infosys. So that is adapting your business model for the reality of a country.

Any other examples?

JCB is a beautiful example. Everyone else came with an excavator. These guys came with a backhoe Bakchoes was 1960s technology, but India needed a backhoe. The country needed something low tech, very versatile and very inexpensive. They also localised to get the price point right. Also everybody optimises a machine for productivity i.e. how much mud can you dig in one hour. These guys optimised it for fuel efficiency i.e. how much mud can I dig per litre of diesel. Every point they made a different decision based on the market. How do you adapt your equipment so that it can run on adulterated diesel and abuse? You can’t find operators to run the machines. So lets start schools for backhoe operators across the countries.

The other companies did not do these things?

Everybody else was saying when the market comes up, then we will do it. These guys created the market and so they own it. Do you have a microwave oven from Samsung?

No…

It doesn’t say time setting. It says dal. It figures out the time and setting on its own.

That is a great innovation…

And it is so simple. And it will also in certain models say dal in Hindi. Is this rocket science or genius? No it is paying attention to your customer. That is all it is.

The interview originally appeared in Daily News and Analysis on July 27, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why does UPA want to feed 67% if only 21% of India is poor?

Vivek Kaul

Poverty in India has fallen between 2004-05 and 2011-12, or so suggests data recently released by the Planning Commission. The poverty ratio was 37.2% in 2004-05 and fell to 21.9% by 2011-12.

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance(UPA) has been quick to claim credit for this fall in poverty. The opposition parties from the left and the right have slammed the government, and questioned the numbers put out by the Planning Commission.

So who is right on this occasion? The government? Or the opposition? Before we get around to answering these questions, it is first important to understand how the Planning Commission decides who is poor and who is not.

A poverty line separates the poor section of the population from the non poor section. Those below the poverty line are deemed to be poor and those above it are deemed to be not poor. And what exactly is a poverty line? As S Subramanian writes in The Poverty Line “A poverty line is identified in monetary units as the level of income or consumption expenditure required in order to avoid poverty.”

So how is the level of income or consumption expenditure required in order to avoid poverty decided on? An essential criterion for avoiding poverty is the availability of adequate nutrition, writes Subramanian. Hence, a calorie norm is identified. The amount of money required to consume the identified number of food calories becomes the cut off point, or the poverty line. Those who consume less than that are deemed to be poor.

This criteria was first clearly addressed by the Indian planners in 1979 in a Planning Commission Report of the Task Force of Minimum Needs and Effective Consumption Demand. As Subramanian writes “In identifying consumption expenditure poverty norms for India, the Task Force employed a nutritional norm of 2,435 (rounded off to 2,400) kilocalories per person per day in rural areas, and a norm of 2,095 calories (rounded off to 2,100) kilocalories per person per day in the urban areas. These were average figures based on calorie allowances recommended by a Nutrition Expert Group in 1968…The Task Force was able to come up with an ‘average’ requirement of calories for what one might call a ‘representative’ Indian, in each of the rural and urban areas of the country.”

So what does this mean? It means that anyone in rural India consuming less than 2,400 kilocalories per day was deemed to be poor. For urban India this number was at 2,100 kilocalories. Through a statistical regression the total expenditure necessary to consume either 2,400 kilocalories or 2,100 kilocalories was estimated.

The Tendulkar Committee formula, a new formula to estimate the poverty line, came into effect in 2009. This formula, other than considering the expenditure on food, also took expenses on education, health and clothing into account.

When Professor Suresh Tendulkar changed the formula he argued that the old formula did not take into account the fact that calorie intake had dropped to 1770 kilocalories in urban areas. Despite this change the influence of the old calorie norm on the new formula is considerable, feel experts.

And how much is the expenditure as per the Tendulkar Committee formula ? As the Press Note on Poverty Estimates, 2011-12, released by the Planning Commission points out “for rural areas the national poverty line…is estimated at Rs. 816 per capita per month and Rs. 1,000 per capita per month in urban areas. Thus, for a family of five, the all India poverty line in terms of consumption expenditure would amount to about Rs. 4,080 per month in rural areas and Rs. 5,000 per month in urban areas.”

Assuming 30 days in a month, this expenditure comes to Rs 27.5 per day for the rural areas and Rs 33.33 for urban areas. Hence, anyone whose expenditure per day is less than these amounts is categorised as poor.

How adequate is this poverty line of Rs 27.5-Rs 33.33 per day? If one were to believe film star turned Congress politician Raj Babbar, this amount is more than enough. “Even today in Mumbai city, I can have a full meal at Rs 12. No no not vada paav. So much of rice, dal sambhar and with that some vegetables are also mixed ,” he told reporters today (i.e. July 25, 2013).

Of course, this clearly proves that Mr Babbar has not stepped onto the streets of Mumbai for a very long time. His days of struggle in the film industry having been long over.

Even if we believe that one can get a meal for Rs 12 in Mumbai, eating is not the only expenditure that a man needs to incur in order to survive.

Given this, it is easy to prove that the poverty line in India has been set at a very low level. There have been a spate of comments criticising this. Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh called the Planning Commission figures a cruel joke on the poor. “I would like to ask the Prime Minister and Congress president whether they could have their meal in just Rs 32(if one divides Rs 1000 by 31 days, it comes to Rs 32.25),” Chouhan said.

This is something that Praful Patel of the Nationalist Congress Party, which is a part of the UPA, agreed with. “The ceiling set by them (Planning Commission) is totally wrong. In today’s time, Commission should set a new ceiling keeping in mind inflation and high cost of living. We do not agree with this data,” Patel said. Brinda Karat of the CPI(M) said that the Planning Commission figures were “dubious” and “discredited” and added “salt to the wounds of the poor”. Similar reactions came in from other political parties as well.

So, the poverty line in India is at a very low level and hence needs to be increased is a conclusion that can be easily drawn from. As N.C. Saxena, member of the National Advisory Council, who headed a Planning Commission panel on poverty told The Hindu “the narrow definition of poverty we have been using, where the line is really what I call a ‘kutta-billi’ line; only cats and dogs can survive on it.”

But raising the poverty line is not simple and has serious implications. As Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya write in India’s Tryst with Destiny “While reasonable people may differ on whether it is reasonable to further raise the poverty line, the subject is far more complex than commonly appreciated.”

And why is that the case? “The dilemma in raising the poverty lines is best brought out by considering the implications of poverty lines that are significantly higher than those currently in use and are advocated by many of the current critics of the Planning Commission. Thus, for example, suppose we raise the rural poverty line to Rs 80 and the urban one to Rs 100 at 2009-10 prices. What would these lines imply?” ask Bhagwati and Panagariya.

This would designate 95% of the rural population and 85% of the urban population to be poor. The impact of this would be that the money that the government spends to tackle poverty would be spread over a much larger number of people and thus would have less impact in tackling poverty. As Bhagwati and Panagariya point out “With tax revenues still relatively modest, significant redistribution in favour of the destitute requires limiting such redistributions to the bottom 40 percent or so of the population. Spreading them thinly over a vast population will give too little to the destitute to make a major dent in poverty.”

Lets understand this through an example. Let us say there are 100 people. Of this 20 are deemed to be poor. The government decides to spend Rs 100 to help them. Hence, on an average each one of them benefits to the extent of Rs 5.

Now lets the definition of poverty is changed and 90 out of 100 people, are deemed to be poor. The government still spends Rs 100 on them. The benefit per person comes down to a much lower Rs 1.11 (Rs 100/90). Hence, the more poor lose out at the cost of the less poor.

In fact, this is not the first time such a situation has arisen. In 1962, the Perspective Planning Department (PPD) of the Planning Commission had discussed a similar dilemma. As Subramanian writes partly quoting a PPD document “’The balanced diet recommended by the Nutrition Advisory Committee together with a modest standard of consumption for other items would cost approximately Rs 35 per head (per month). But at present less than 20% of our population can afford it’…The implication is quite clear. A poverty line of Rs 35 per person per month would have plunged 80 per cent of the Indian population into poverty: wiser counsel advocated a more modest norm of Rs 20 per person per month.” This brought down the poverty rate to 60%.

Hence, there is no point in pushing up the poverty line without having the resources to tackle it. If resources are limited they should be deployed to help those who need it the most.

But the Congress led UPA government has done exactly the opposite by getting the President to sign on the Food Security Ordinance. The food security scheme aims at providing subsidised rice and wheat to nearly 82 crore Indians or 67% of the total population.

This effectively means that the government thinks that 67% of the Indian population is poor and cannot afford to buy rice and wheat at market rates. But as per the current poverty line only 21.9% of the population is not getting adequate nutrition. So which is the right number? 21.9% or 67%? The Congress led UPA government needs to answer that question.

It seems the government is working on a new poverty line to justify the massive expenditure that it will incur on the Food Security scheme. As The Hindu reports “economists advising the Ministry of Rural Development have told The Hindu that the exclusion criteria to be derived from the ongoing Socio-Economic and Caste Census are likely to leave out the top 35 per cent of the population while the bottom 65 per cent will be considered below poverty line.”

Meanwhile, it will claim that the poverty has come down on the basis of the current poverty line and numbers put out by the Planning Commission because of the social programmes it has launched over the last few years.

As the old saying goes “heads I win, tails you lose”.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 25, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why RBI killed the debt fund

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is doing everything that it can do to stop the rupee from falling against the dollar. Yesterday it announced further measures on that front.

Each bank will now be allowed to borrow only upto 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks in the short term and it currently stands at 7.25%.

Sometime back the RBI had put an overall limit of Rs 75,000 crore, on the amount of money that banks could borrow from it, at the repo rate. This facility of banks borrowing from the RBI at the repo rate is referred to as the liquidity adjustment facility.

The limit of Rs 75,000 crore worked out to around 1% of total deposits of all banks. Now the borrowing limit has been set at an individual bank level. And each bank cannot borrow more than 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. This move by the RBI is expected bring down the total quantum of funds available to all banks to Rs 37,000 crore, reports The Economic Times.

In another move the RBI tweaked the amount of money that banks need to maintain as a cash reserve ratio(CRR) on a daily basis. Banks currently need to maintain a CRR of 4% i.e. for every Rs 100 of deposits that the banks have, Rs 4 needs to set aside with the RBI.

Currently the banks need to maintain an average CRR of 4% over a reporting fortnight. On a daily basis this number may vary and can even dip under 4% on some days. So the banks need not maintain a CRR of Rs 4 with the RBI for every Rs 100 of deposits they have, on every day.

They are allowed to maintain a CRR of as low as Rs 2.80 (i.e. 70% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. Of course, this means that on other days, the banks will have to maintain a higher CRR, so as to average 4% over the reporting fortnight.

This gives the banks some amount of flexibility. Money put aside to maintain the CRR does not earn any interest. Hence, if on any given day if the bank is short of funds, it can always run down its CRR instead of borrowing money.

But the RBI has now taken away that flexibility. Effective from July 27, 2013, banks will be required to maintain a minimum daily CRR balance of 99 per cent of the requirement. This means that on any given day the banks need to maintain a CRR of Rs 3.96 (99% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. This number could have earlier fallen to Rs 2.80 for every Rs 100 of deposits. The Economic Times reports that this move is expected to suck out Rs 90,000 crore from the financial system.

With so much money being sucked out of the financial system the idea is to make rupee scarce and hence help increase its value against the dollar. As I write this the rupee is worth 59.24 to a dollar. It had closed at 59.76 to a dollar yesterday. So RBI’s moves have had some impact in the short term, or the chances are that the rupee might have crossed 60 to a dollar again today.

But there are side effects to this as well. Banks can now borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI under the liquidity adjustment facility at the repo rate of 7.25%. If they have to borrow money beyond that they need to borrow it at the marginal standing facility rate which is at 10.25%. This is three hundred basis points(one basis point is equal to one hundredth of a percentage) higher than the repo rate at 10.25%. Given that, the banks can borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI at the repo rate. Hence, the marginal standing facility rate has effectively become the repo rate.

As Pratip Chaudhuri, chairman of State Bank of India told Business Standard “Effectively, the repo rate becomes the marginal standing facility rate, and we have to adjust to this new rate regime. The steps show the central bank wants to stabilise the rupee.”

All this suggests an environment of “tight liquidity” in the Indian financial system. What this also means is that instead of borrowing from the RBI at a significantly higher 10.25%, the banks may sell out on the government bonds they have invested in, whenever they need hard cash.

When many banks and financial institutions sell bonds at the same time, bond prices fall. When bond prices fall, the return or yield, for those who bought the bonds at lower prices, goes up. This is because the amount of interest that is paid on these bonds by the government continues to be the same.

And that is precisely what happened today. The return on the 10 year Indian government bond has risen by a whopping 33 basis points to 8.5%. Returns on other bonds have also jumped.

Debt mutual funds which invest in various kinds of bonds have been severely impacted by the recent moves of the RBI. Since bond prices have fallen, debt mutual funds which invest in these bonds have faced significant losses.

In fact, the data for the kind of losses that debt mutual funds will face today, will only become available by late evening. But their performance has been disastrous over the last one month. And things should be no different today.

Many debt funds have lost as much as 5% over the last one month. And these are funds which give investors a return of 8-10% over a period of one year. So RBI has effectively killed the debt fund investors in India.

But then there was nothing else that it could really do. The RBI has been trying to manage one side of the rupee dollar equation. It has been trying to make rupee scarce by sucking it out of the financial system.

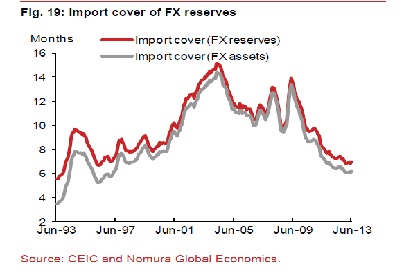

The other thing that it could possibly do is to sell dollars and buy rupees. This will lead to there being enough dollars in the market and thus the rupee will not lose value against the dollar. The trouble is that the RBI has only so many dollars and it cannot create them out of thin air (which it can do with rupees). As the following graph tells us very clearly, India does not have enough foreign exchange reserves in comparison to its imports.

The ratio of foreign exchange reserves divided by imports is a little over six. What this means is that India’s total foreign exchange reserves as of now are good enough to pay for imports of around a little over six months. This is a precarious situation to be in and was only last seen in the 1990s, as is clear from the graph.

The government may be clamping down on gold imports but there are other imports it really doesn’t have much control on. “The commodity intensity of imports is high,” write analysts of Nomura Financial Advisory and Securities in a report titled India: Turbulent Times Ahead. This is because India imports a lot of coal, oil, gas, fertilizer and edible oil. And there is no way that the government can clamp down on the import of these commodities, which are an everyday necessity. Given this, India will continue to need a lot of dollars to import these commodities.

Hence, RBI is not in a situation to sell dollars to control the value of the rupee. So, it has had to resort to taking steps that make the rupee scarce in the financial system.

The trouble is that this has severe negative repercussions on other fronts. Debt fund investors are now reeling under heavy losses. Also, the return on the 10 year bonds has gone up. This means that other borrowers will have to pay higher interest on their loans. Lending to the government is deemed to be the safest form of lending. Given this, returns on other loans need to be higher than the return on lending to the government, to compensate for the greater amount of risk. And this means higher interest rates.

The finance minister P Chidambaram has been calling for lower interest rates to revive economic growth. But he is not going to get them any time soon. The mess is getting messier.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 24, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)