Vivek Kaul

Every country needs foreign currency to pay for its imports. The foreign currency needed is typically the American dollar or the euro. This foreign currency is earned through exports. India is no different on this account.

But what happens when the imports are greater than exports as is the case with India? This leads to a situation where the country does not have enough foreign currency to pay for its imports. How does the country then pay for its imports? What comes to the rescue are remittances of foreign currency made by the citizens of the country living abroad. These remittances can then be used to pay for imports. India is the world’s largest receiver of remittances. In 2012, it received $69 billion, as per World Bank data.

But even with such large remittances being made, a country may not have enough foreign currency going around to pay for its imports. In such a situation, the country is said to be running a current account deficit (CAD). In technical terms, the CAD is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances.

In 2012, India’s CAD stood at $93 billion, which was only second to the United States in absolute terms. As Amay Hattangadi and Swanand Kelkar of Morgan Stanley Investment Management point out in a report titled Don’t Take Your Eye of the Ball “At $93billion, India’s CAD in 2012 was second only to the US in absolute terms, and higher than the UK, Canada and France.”

The following table from the report shows the list of countries with the highest CAD in absolute terms. Even if we compare CAD as a percentage of GDP, only South Africa and Turkey are ranked ahead of India.

India’s high CAD is primarily because of the fact that it has to import a large portion of the oil it consumes. For the year ending March 31, 2013, the country imported $169.25 billion worth of oil. This forms nearly 34.4 percent of India’s total imports.

With oil prices falling in the recent past, this has given reason for hope that India will be able to control its CAD in the time to come. The price of the Indian basket of crude oil stood at $101.58 per barrel as on May 3, 2013. On January 31, 2013, the price was $111.44 per barrel. So, clearly the oil price has fallen over the last three months and this should help India control the CAD is a logical conclusion being made.

And this has led to a lot of optimism among the lot who run this country. The finance minister on a recent visit to the United States said, “If exports rise sharply, if the oil prices soften more quickly, the current account deficit could be contained at 2.5 percent even by next year.”

This is being a tad too optimistic, as Hattangadi and Kelkar put it, “even if we assume lower energy prices will result in a saving of about $20 billion in the current fiscal year”. This means the CAD will stand at over $70 billion, which is not a small amount by any stretch of imagination.

What has also helped in controlling a galloping CAD to some extent has been a fall in the price of gold and various steps taken by the government to discourage buying of gold, like increasing the import duty on it. Gold imports declined by 11.8 percent to $50 billion during the period April 2012-February 2013.

Falling oil and gold prices may have come as a boon but what has somewhat negated this effect is rise in the import of coal. In the first nine months of the financial year 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012), coal imports jumped 70 percent. This trend is likely to continue. “Despite having the fifth largest coal reserves in the world, India’s coal imports this year may rise to 130 million tonnes, up 50 percent from two years ago,” write Hattangadi and Kelkar. In 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013), the coal imports are expected to be around 110 million tonnes.

So unless India takes concrete steps to address its energy sufficiency, its high CAD is likely to continue. As Hattangadi and Kelkar write, “India has done little to adequately address energy self-sufficiency. After declining for almost 20 years until 2005, US energy self-sufficiency has gone up from 69 percent to 80 percent. In contrast, India’s energy self sufficiency has been falling from 90 percent in 1984 to 63 percent in 2011.”

With the coalgate scam currently haunting the government, it is unlikely that much will happen in the area of encouraging private production of coal in the months to come.

As mentioned earlier India ran a CAD of $93 billion in 2012-2013. What this means is that the sum total of foreign exchange that came in through exports and remittances was not enough to pay for imports. So where did the remaining foreign exchange to pay for imports come from?

This is where foreign investors came in. Foreign investment in the form of foreign direct investment and portfolio investment (the money that comes into the stock market and the debt market) has been in the range of $40-50 billion in the five out of last six years.

Foreign investors bring money into India in the form of dollars, euros or yen, for that matter, and exchange it for rupees to invest in India. This foreign exchange accumulates with the Reserve Bank of India or any of the banks, and is bought by importers looking to pay for their imports.

Hence it is safe to say that to a large extent India remains dependant on foreign investors to continue financing its CAD. And that explains why Finance Minister P Chidambaram has been on several foreign roadshows over the last few months trying to encourage foreign investors to invest more in India.

But there are two problems here. As Chidambaram said in the budget speech earlier this year, “The key to restart the growth engine is to attract more investment, both from domestic investors and foreign investors. Investment is an act of faith.”

And faith can turn around very quickly. When the financial crisis erupted in 2008-09, foreign investment fell to $8 billion from the $40-50 billion level. Any sense of a crisis can lead to foreign investors stopping to bring money into India. They might also start withdrawing the money they have invested in India.

The other problem here is that how does the finance minister motivate foreigners to invest in India, when Indian businessmen are looking to invest abroad. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations, “At a time when India needs its businessmen to reinvest more aggressively at home in order for the country to hit its growth target of 8 to 9 percent, they are looking abroad. Overseas operations of Indian companies now account for more than 10% of overall corporate profitability, compared with 2 percent just five years ago.”

And if all this wasn’t enough imports are not the only thing competing for foreign currency. Over the last few years more and more Indian businesses have borrowed abroad given the low interest rates that prevail internationally. This money now needs to be returned. Hattangadi and Kelkar estimate that “the total amount of debt that will likely come up for redemption or refinancing in the current year is about $165billion, which is about $20billion higher than last year.” Hence, imports and repayment of debt will be competing for foreign currency.

So yes, oil prices and gold prices are falling, but there are other reasons to worry about, when it comes to the current account deficit, something the political class that runs this country, isn’t really talking about.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 7,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Oil

Why the dollar continues to look as good as gold

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few years a mini industry predicting the demise of the dollar has evolved. This writer has often been a part of it. But nothing of that sort has happened.

There are fundamental reasons that have led this writer and other writers to believe that dollar is likely to get into trouble sooner rather than later. The main reason is the rapid rate at which the Federal Reserve of United States has printed dollars over the last few years. This rapid money printing is expected to create high inflation sometime in the future.

But whenever markets have sensed any kind of trouble in the last few years money has rapidly moved into the dollar. In fact, even when the rating agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded America’s AAA status, money moved into the dollar. It couldn’t have been more ironical.

What is interesting nonetheless that the doubts on the continued existence of the dollar are getting graver by the day. Gillian Tett, the markets and finance commentator of The Financial Times has a very interesting example on this in her latest column Is Dollar As Good as Gold published on March 1, 2013.

As Tett writes “Should we all worry about the outlook for the mighty American dollar? That is a question that many economists and market traders have pondered as economic pressures have grown. But in recent weeks Virginia’s politicians have been discussing it with renewed zeal. Last month Bob Marshall, a local Republican, submitted a bill to the local assembly calling on the state to study whether it should create its own “metallic-based” currency.”

The reason for this as the bill pointed out was that “Unprecedented monetary policy actions taken by the Federal Reserve … have raised concern over the risk of dollar debasement.”

In fact Virginia is not the only state in the United States that has been talking about a currency backed by a precious metal(read gold). As Tett puts it “So guffaw at the Virginia bill if you like. And if you want an additional chuckle, you might also note that a dozen other state assemblies, in places such as North and South Carolina, have discussed similar ideas; indeed, Utah has a gold and silver depository which is trying to back debit cards with gold.”

The point is that the debate on the demise of the dollar if it continues to be printed at such a rapid rate, is now moving into the mainstream.

So what will be the fate of the US dollar? Will it continue to be at the heart of the global financial system? These are questions which are not easy to answer at all. There are too many interplaying factors involved.

While there are fundamental reasons behind the doubts people have over the future of the dollar. There are equally fundamental reasons behind why the dollar is likely to continue to survive. But one good place to start looking for a change is the composition of the total foreign exchange reserves held by countries all over the world. The International Monetary Fund puts out this data. The problem here is that a lot of countries declare only their total foreign exchange reserves without going into the composition of those reserves. Hence the fund divides the foreign exchange data into allocated reserves and total reserves. Allocated reserves are reserves for countries which give the composition of their foreign exchange reserves and tell us exactly the various currencies they hold as a part of their foreign exchange reserves.

Dollars formed 71% of the total allocable foreign exchange reserves in 1999, when the euro had just started functioning as a currency. Since then the proportion of foreign exchange reserves that countries hold in dollars has continued to fall. In fact in the third quarter of 2008 (around the time Lehman Brothers went bust) dollars formed around 64.5% of total allocable foreign exchange reserves. This kept falling and by the first quarter of 2010 it was at 61.8%. It has started rising since then and as per the last available data as of the third quarter of 2012, dollars as a proportion of total allocable foreign exchange reserves are at 62.1%. The fall of the dollar has all along been matched by the rise of the euro. But with Europe being in the doldrums lately it is unlikely that countries will increase their allocation to the euro in the days to come. Between first quarter of 2010 and the third quarter of 2012, the holdings of euro have fallen from 27.3% to 24.14%.

So the proportion of dollar in the total allocable foreign exchange reserves has fallen from 71% to 62.1% between 1999 and 2012. But then dollar as a percentage of total allocable foreign exchange reserves in 2012 was higher than it was in 1995, when the proportion was 59%.

So when it comes to international reserves, the American dollar still remains the currency of choice, despite the continued doubts raised about it. One reason for it is the fact that there has been no real alternative for the dollar. Euro was seen as an alternative but with large parts of Europe being in bigger trouble than America, that is no longer the case. Japan has been in a recession for more than two decades not making exactly yen the best currency to hold reserves in.

The British Pound has been in doldrums since the end of the Second World War. And the Chinese renminbi still remains a closed currency given that its value is not allowed to freely fluctuate against the dollar.

So that leaves really no alternative for countries to hold their reserves in other than the American dollar. But that is not just the only reason for countries to hold onto their reserves in dollars. The other major reason why countries cannot do away with the dollar given that a large proportion of international transactions still happen in dollar terms. And this includes oil.

The fact that oil is still bought and sold in American dollars is a major reason why American dollar remains where it is, despite all attempts being made by the American government and the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, to destroy it. And for this the United States of America needs to be thankful to Franklin D Roosevelt, who was the President from 1933 till his death in 1945 (in those days an individual could be the President of United States for more than two terms).

At the end of the Second World War Roosevelt realised that a regular supply of oil was very important for the well being of America and the evolving American way of life. He travelled quietly to USS Quincy, a ship anchored in the Red Sea. Here he was met by King Ibn Sa’ud of Saudi Arabia, a country, which was by then home to the biggest oil reserves in the world.

The United States’ obsession with the automobile had led to a swift decline in domestic reserves, even though America was the biggest producer of oil in the world at that point of time. The country needed to secure another source of assured supply of oil. So in return for access to oil reserves of Saudi Arabia, King Ibn Sa’ud was promised full American military support to the ruling clan of Sa’ud..

Saudi Arabia over the years has emerged as the biggest producer of oil in the world. It also supposedly has the biggest oil reserves. It is also the biggest producer of oil within the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the oil cartel. Hence this has ensured that OPEC typically does what Saudi Arabia wants it to do. Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia has had the almost unquestioned support of what are known as the sheikhdom states of Bahrain, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

In fact, in the late 1970s efforts were made by other OPEC countries, primarily Iran, to get OPEC to start pricing oil in a basket of currencies (which included the dollar) but that never happened as Saudi Arabia put its foot down on any such move. This led to oil being continued to be priced in dollars and was a major reason for the dollar continuing to be the major international reserve currency.

It is important to remember that the American security guarantee made by President Roosevelt after the Second World War was extended not to the people of Saudia Arabia nor to the government of Saudi Arabia but to the ruling clan of Al Sa’uds. Hence, it is in the interest of the Al Sa’ uds to ensure that oil is continued to be priced in American dollars.

And until oil is priced in dollars, any theory on the dollar being under threat will have to be taken with a pinch of salt because the world will need American dollars to buy oil. Also it is important to remember that financially America might be in a mess, but by and large it still remains the only superpower in the world. In 2010, the United States spent $698billion on defence. This was 43% of the global total.

So dollar in a way will continue to be as good as gold. Until it snaps.

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 5, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek and continues to actively bet against the dollar by buying gold through the mutual fund route)

Subsidies = Inflation = Gold problem

The government has a certain theory on gold as per which buying gold is harmful for the Indian economy. Allow me to elaborate starting with something that P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, recently said “I…appeal to the people to moderate the demand for gold.”

India produces very little of the gold it consumes and hence imports almost all of it. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. When someone from India buys gold internationally, Indian rupees are sold and dollars are bought. These dollars are then used to buy gold.

So buying gold pushes up demand for dollars. This leads to the dollar appreciating or the rupee depreciating. A depreciating rupee makes India’s other imports, including our biggest import i.e. oil, more expensive.

This pushes up the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) as well as our fiscal deficit (the difference between what the government earns and what it spends).

The fiscal deficit goes up because as the rupee depreciates the oil marketing companies(OMCs) pay more for the oil that they buy internationally. This increase is not totally passed onto the Indian consumer. The government in turn compensates the OMCs for selling kerosene, cooking gas and diesel, at a loss. Hence, the expenditure of the government goes up and so does the fiscal deficit. A higher fiscal deficit means greater borrowing by the government, which crowds out private sector borrowing and pushes up interest rates. Higher interest rates in turn slow down the economy.

This is the government’s theory on gold and has been used to in the recent past to hike the import duty on gold to 6%. But what the theory doesn’t tells us is why do Indians buy gold in the first place? The most common answer is that Indians buy gold because we are fascinated by it. But that is really insulting our native wisdom.

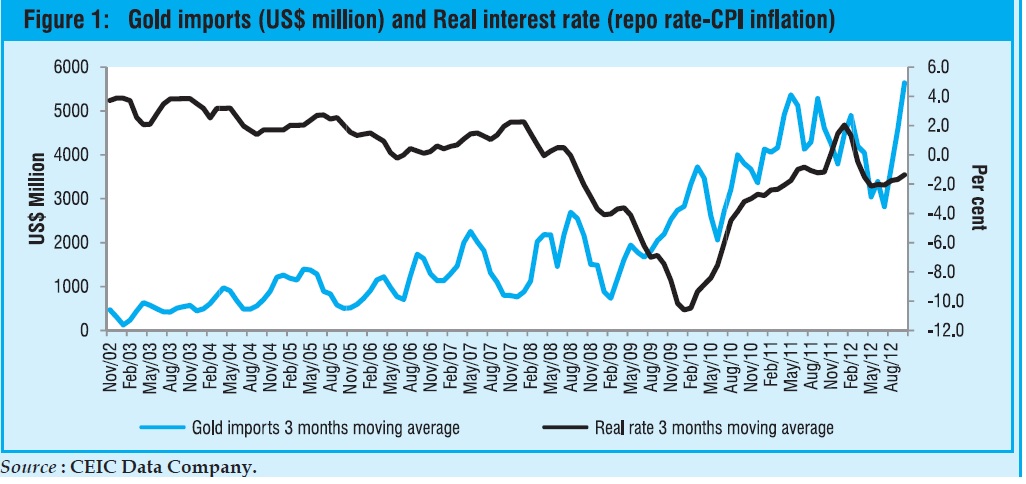

World over gold is bought as a hedge against inflation. This is something that the latest economic survey authored under aegis of Raghuram Rajan, the Chief Economic Advisor to the government, recognises. So when inflation is high, the real returns on fixed income investments like fixed deposits and banks is low. As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.”(as can be seen from the accompanying table at the start)

In simple English, people buy gold when inflation is high and the real return from fixed income investments is low. That has precisely what has happened in India over the last few years. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Survey points out.

High inflation in India has been the creation of all the subsidies that have been doled out by the UPA government. As the Economic Survey puts it “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

Inflation thus is a creation of all the subsidies being doled out, says the Economic Survey. And to stop Indians from buying gold, inflation needs to be controlled. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance,” the Survey points out. So if Indians are buying gold despite its high price and imposition of import duty, they are not be blamed.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why FM is tickling the markets: it’s his only chance

Vivek Kaul

So P Chidambaram’s at it again, trying to bully the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to cut interest rates. “In our view, the government and monetary authority must point in the same direction and walk in the same direction. As we take steps on the fiscal side, RBI should take steps on the monetary side,” the Union Finance Minister told the Economic Times.

Economic theory suggests that when interest rates are low, consumers and businesses tend to borrow more. When consumers borrow and spend money businesses benefit. When businesses benefit they tend to expand their operations by borrowing money. And this benefits the entire economy and it grows at a much faster rate.

But then economics is no science and so theory and practice do not always go together. If they did the world we live would be a much better place. As John Kenneth Galbraith points out in The Economics of Innocent Fraud: “If in recession the interest rate is lowered by the central bank, the member banks are counted on to pass the lower rate along to their customers, thus encouraging them to borrow. Producers will thus produce goods and services, buy the plant and machinery they can afford now and from which they can make money, and consumption paid for by cheaper loans will expand..The difficulty is that this highly plausible, wholly agreeable process exists only in well-established economic belief and not in real life… Business firms borrow when they can make money and not because interest rates are low.”

While India is not in a recession exactly, economic growth has slowed down considerably this year. And this has led to businesses not borrowing. As a story in theBusiness Standard points out “At a recent meeting with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), 10 of the country’s top bankers said companies were still keeping expansion plans on hold, as business growth continued to be slow in an uncertain economic environment. Nine of 10 bankers who attended the meeting admitted their sanctioned loan pipeline was shrinking fast due to tepid demand.”

This is borne out even by RBI data. The incremental credit deposit ratio for scheduled commercial banks between March 30, 2012 and September7, 2012, stood at 14.4%. This meant that for every Rs 100 that bank raised as deposits during this period they only lent out Rs 14.4 as loans. Hence, businesses are not borrowing to expand neither are consumers borrowing to buy flats, cars, motorcycles and consumer durables.

One reason for this lack of borrowing is high interest rates. But just cutting interest rates won’t ensure that the borrowing will pick up. As Galbraith aptly puts it business firms borrow when they can make money. But that doesn’t seem to be the case right now. Take the case of the infrastructure sector which was one of the most hyped sectors in 2007. As Swaminathan Aiyar points out in the Times of India “The government claims India is a global leader in public-private partnerships in infrastructure. The private sector financed 36% of infrastructure in the 11th Plan (2007-12 ),and is expected to finance fully 50% in the 12th Plan. This is now a pie in the sky. Corporations that charged into this sector have suffered heavy losses. They expected a gold mine, but found only quicksand. They have been hit by financially disastrous time and cost overruns.”

Clearly these firms are not in a state to borrow. Several other business sectors are in a mess. Airlines are not going anywhere. The big Indian companies that got into organised retail have lost a lot of money. The telecom sector is bleeding. So just because interest rates are low it doesn’t automatically follow that businesses will borrow money.

“If you take a poll of the top 100 companies in the country, you will find them saying nothing has changed despite the reforms. Confidence will return only if things start happening on the ground,” a Chief Executive of a leading foreign bank in India was quoted as saying in the Business Standard.

Confidence on the ground can only come back once businesses start feeling that this business is committed to genuine economic reform, there is lesser corruption, more transparency, so and so forth. These things cannot happen overnight.

Consumers are also feeling the heat with salary increments having been low this year and the consumer price inflation remaining higher than 10%. Borrowing doesn’t exactly make sense in an environment like this, when just trying to make ends meet has become more and more difficult.

Given these reasons why has Chidambaram been after the RBI to try and get it to cut interest rates? The thing is that the finance minister is not so concerned about consumers and businesses, but what he is concerned about is the stock market.

With interest rates on fixed income investments like bank fixed deposits, corporate fixed deposits, debentures, etc, being close to 10%, there is very little incentive for the Indian investor to channelise his money into the stock market.

Since the beginning of the year the domestic institutional investors have taken out Rs 38,000.5 crore from the stock market. If the RBI does cut interest rates as Chidambaram wants it to, then investing in fixed income investments will become less lucrative and this might just get Indian investors interested in the stock market.

The lucky thing is that even though Indian investors have been selling out of the stock market, the foreign investors have been buying. Since the beginning of the year the foreign institutional investors have bought stocks worth Rs 72,065.2 crore. This has ensured that stock market has not fallen despite the Indian investors selling out.

If the RBI does cut interest rates and that leads Indian investors getting back into the stock market there might be several other positive things that can happen. If Indian investors turn net buyers and the stock market goes up, more foreign money will come in. This will push up the stock market even further up.

The other thing that will happen with the foreign money coming in is that the rupee will appreciate against the dollar. When foreigners bring dollars into India they have to sell those dollars and buy rupees. This increases the demand for the rupee and it gains value against the dollar.

An appreciating rupee will also spruce up returns for foreign investors. Let us say a foreign investor gets $1million to invest in Indian stocks when one dollar is worth Rs 55. He converts the dollars into rupees and invests Rs 5.5 crore ($1million x Rs 55) into the Indian market. He invests for a period of one year and makes a return of 10%. His investment is now worth Rs 6.05 crore. One dollar is now worth Rs 50. When he converts the investors ends up with $1.21million or a return of 21% in dollar terms. An appreciating rupee thus spruces up his returns. This prospect of making more money in dollar terms is likely to get more and more foreign investors into India, which will lead to the rupee appreciating further. So the cycle will feeds on itself.

In the month of September 2012, foreign investors have bought stocks worth Rs 20,807.8 crore. Correspondingly, the rupee has gained in value against the dollar. On September 1, 2012, one dollar was worth Rs 55.42. Currently it quotes at around Rs 52.8. This means that the rupee has appreciated against the dollar by 4.72%.

An immediate impact of the appreciating rupee is that it brings down the oil bill. Oil is sold internationally in dollars. Let us say the Indian basket of crude oil is selling at $108 per barrel (one barrel equals 159 litres). If one dollar is worth Rs 55.4 then India has to pay Rs 5983.2 for a barrel of oil. If one dollar is worth Rs 52.8, then India has to pay Rs 5702.4 per barrel. So as the rupee appreciates the oil bill comes down.

The oil marketing companies (OMCs) sell diesel, kerosene and cooking gas at a price which is lower than the cost price and thus incur huge losses. The government compensates the OMCs for these losses to prevent them from going bankrupt. This money is provided out of the annual budget of the government under the oil subsidy account. But as the rupee appreciates and the losses come down, the oil subsidy also comes down. This means that the expenditure of the government comes down as well, thus lowering the fiscal deficit. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

This is how a rising stock market may lead to a lower fiscal deficit. But that’s just one part of the argument. A rising stock market will also allow the government to sell some of the shares that it owns in public sector enterprises to the general public. The targeted disinvestment for the year is Rs 30,000 crore. While that can be easily met the government has to exceed this target given that the government is unlikely to meet the fiscal deficit target of 5.1% of GDP as its subsidy bill keeps going up. The Kelkar Committee recently estimated that the fiscal deficit level can even reach 6.1% of the GDP.

For the government to exceed this target the stock markets need to continue to do well. It is a well known fact people buy stocks only when the stock markets have rallied for a while. As Akash Prakash writes in the Business Standard “The finance minister will have to do a lot more than raise Rs 40,000 crore from spectrum and Rs 30,000 crore from divestment. We will need to see movement on selling the SUUTI (Specified Undertaking of UTI) stakes, strategic assets like Hindustan Zinc, land with companies like VSNL, coal block auctions, etc. To enable the government to raise resources of the required magnitude, the capital markets have to remain healthy, both to absorb equity issuance and to enable companies to raise enough debt resources to participate in these asset auctions.”

Given this the stock market has a very important role to play in the scheme of things. Controlling the burgeoning fiscal deficit remains the top priority for the government. But it is easier said than done. “Given the difficulty in getting the coalition to accept the diesel hike and LPG-targeting measures, there are limitations as to how much the current subsidies and revenue expenditure can be compressed. We can see some further measures on fuel price hikes and maybe some movement on a nutrient-based subsidy on urea; but with elections only 15-18 months away, there are serious political costs to any subsidy cuts,” points out Prakash.

Over and above this with elections around the corner the government is also likely to announce more freebies. Money to finance this also needs to come from somewhere. As Prakash writes “There is also intense pressure on the government to roll out more freebies through the right to food, free medicines and so on. If expenditure compression is intensely difficult in the run-up to an election cycle, higher revenue is the only way to control the fiscal deficit.”

For the government to raise a higher revenue it is very important that more and more money keeps coming into the stock market. For this to happen interest rates need to fall. And that is something that D Subbarao the governor of RBI controls and not Chidambaram.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on October 1, 2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/why-fm-is-tickling-the-markets-its-his-only-chance-474908.html

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected]

‘India grows at night while the government sleeps’

Gurcharan Das is an author and a public intellectual. He is the author of The Difficulty of Being Good: On the Subtle Art of Dharma which interrogates the epic, Mahabharata. His international bestseller, India Unbound, is a narrative account of India from Independence to the turn of the century. His latest book India Grows At Night – A Liberal Case For a Strong State (Penguin Allen Lane)has just come out. He was also formerly the CEO of Proctor & Gamble India. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul on why Gurgaon made it and Faridabad didn’t, how the actions of Indira Gandhi are still hurting us, why he cannot vote for anyone in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections and why democracy has to start in your own backyard if it has to succeed.

Gurcharan Das is an author and a public intellectual. He is the author of The Difficulty of Being Good: On the Subtle Art of Dharma which interrogates the epic, Mahabharata. His international bestseller, India Unbound, is a narrative account of India from Independence to the turn of the century. His latest book India Grows At Night – A Liberal Case For a Strong State (Penguin Allen Lane)has just come out. He was also formerly the CEO of Proctor & Gamble India. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul on why Gurgaon made it and Faridabad didn’t, how the actions of Indira Gandhi are still hurting us, why he cannot vote for anyone in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections and why democracy has to start in your own backyard if it has to succeed.

Excerpts:

What do you mean when you say India grows at night?

Essentially the full expression is India grows at night while the government sleeps. I thought that would be insulting to put in the title. So I left it at India Grows at Night. And I subtitled it a liberal case for a strong state. The basic idea is that India has risen from below. We are a bottom up success, unlike China which is a top down success. And because our success is from below, it is more heroic and also more enduring. But we should also grow during the day meaning we should reform our institutions of the state, so that they contribute much more to the growth of the country. We cannot have a story of private success and public failure in India.

Could you explain this through an example?

I start chapter one of the book with a contrast between Faridabad and Gurgaon. If you were living in Delhi in the seventies and eighties, the big story, the place you were going to invest was Faridabad. It had an active municipality. The state government wanted to make it into a showcase for the future. It had a direct line to Delhi. It had host of industries coming in. It had a very rich agriculture. It was the success story. So if you were an investor you would have put your money in Faridabad.

And what about Gurgaon?

In contrast there was this village called Gurgaon not connected to Delhi. No industries. It had rocky soil, so the agriculture was poor. Even the goats did not want to go there. So it was wilderness. And yet 25 years later look at the story. Gurgaon has become an engine of international growth. It is called the millennium city. It has thirty two million square feet of commercial space. It is the residence of all the major multinationals that have come into the country. It has seven golf courses. Every brand name, from BMW to Mercedes Benz, they are all there. And look at Faridabad (laughs)…

Faridabad missed the bus?

Faridabad still hasn’t got the first wave of modernisation that came to India after 1991. It escaped Faridabad. Only now it’s kind of waking up. And Gurgaon did not have a municipality until 2009. This contrast really is in a way the story of India grows at night. And the fact is that the people of Gurgaon deserve a lot of credit because they didn’t sit and wait around. If the police didn’t show up they had private security guards. They even dug bore-wells to make up for the water. The state electricity board did not provide electricity, so they had generators and backup. They used couriers instead of the Post Office. Basically they rose on their own.

So what is the point you are trying to make?

My point is that neither Faridabad nor Gurgaon is India’s model. Faridabad is a model where you have an excessive bureaucracy. Why did Faridabad not succeed? Because the politician and bureaucrats tried to squeeze everything out in the form of licenses. And Gurgaon’s disadvantage turned out to be its advantage. It had no government. So there was nobody to bribe. But at the end of the day Gurgaon would be better off, people would have happier if they had good sanitation, if they had a working transportation system, they had good roads, parks, power etc.

All that is missing…

All the things that you take for granted that you would get in a city, you shouldn’t have to provide them for yourself. This is the point. Neither model is right. And we need to reform the institutions of our state. And we need to create what I call a strong liberal state.

What’s a strong liberal state?

A strong liberal state has three pillars. One an executive that is not paralysed like Delhi is right now, where you have push and drag to get any action done. Second that action of the executive is bounded by the rule of law and third that action is accountable to the people. When I mean a strong state? I am not talking about Soviet Russia or Maoist China. I am not even talking about a benign authoritarian state like Singapore which is very tempting because it has got such high levels of governance. I am talking about classical liberal state the same kind of state that our founding fathers had in mind or the American founding fathers had in mind when they thought about the state. And so that is not easy to achieve.

Why do you say that?

It is not easy to achieve because some elements in these three pillars fight with each other. In other words you have an excessive drive for accountability then the executive gets weakened. I mean right now the Anna Hazare movement has so scared the bureaucrats that they won’t put a signature on a piece of paper. The Anna Hazare movement is a good thing because it awakened the middle class but it also weakened the executive. So, today more important than even economic reforms are institutional reforms i.e. the reform of the bureaucracy. If a person is promoted after twenty years regardless of his performance there are repercussions. If it doesn’t matter whether he is a rascal or outstanding, and both are treated the same, you won’t get high performance. You will get a demoralised bureaucracy. Those are the kind of reforms we need.

What are other such reforms?

Take the case of the judiciary, why should it take us 12 years to get a case settled when it takes two or three years anywhere else? You go to a police station to register an FIR, do you think they will do it? Either you have to bribe somebody or lagao some influence. You have this rising India amidst a very very ineffective state.

One of the things you write about in your book is the fact that India got democracy before it got capitalism. World over it’s been the other way around. How has that impacted our evolution as a country?

That also explains some of our problems. By getting democracy before capitalism, you had a populist wave. The politicians when they thought about going to elections started realising ke bhai we will tell people that I’ll give you four rupee kilo rice and get elected. In Punjab the politicians said we will give free electricity to the farmers and got elected. So you killed your finances through this populism. The states which did this really went bankrupt. Punjab and Andhra Pradesh which did these two things couldn’t pay their salaries to their bureaucrats.

And this started with Nehru’s socialism?

Nehru’s socialism created the illusion of a limitless society, that the state would do everything. Jo kuch hai, which we used to do for ourselves, through our families etc, we now expected the state to do. That was the message given by the socialists. The fact is that the state did not have the capacity. In the courts judges knew their jobs. It was a good judiciary. Even the police was very good but suddenly you expanded the mandate so that half the cases today are government cases. You haven’t been paid a refund. Or the government is taking your land or something and so you go to court. So the guilty in many cases is the state.

What you are suggesting is that the mandate of the state was expanded so much that it couldn’t cope with it?

And they did not expand the capacity. Suddenly you needed a tenfold increase in judges and a tenfold increase in bureaucrats. This is because the jobs you expected this people to do were so much greater. And you told people, especially workers and government servants, that you have rights. So a school teacher suddenly realised that he did not have to attend school, he could get away with it. The person who was his boss or her boss was too scared because of the union of the teachers. So one out of four teachers is absent from our schools. And nothing happens to that person. I am answering your question about how embracing democracy before capitalism hurt us. We became more aware of our rights. We tried to distribute the pie before the pie was baked. Before the chapati was created we started dividing it.

In fact there is a saying in Punjabi ke pind vasiya nahi te mangte pehle aa gaye (the village is still being built and the beggars have already arrived)…

Bilkul. Perfect. That’s an even a better saying. This has been one of the problems. In 1991 we did start building the economy base to support a democracy like ours. But these people fettered away some of the gains. Just see how much subsidy is being given on petroleum products. It is around Rs 1,80,000 crore. I mean you could transform your school system with that kind of money.

And the health system…

Yes even the health system.

How much do you think the socialism of Nehru and Indira Gandhi is holding us back?

The damage that Indira Gandhi did was far greater. Her license raj combined with the mai baap sarkar, this double whammy gave the illusion to the people that the state would do everything. Nehru had never talked about a mai baap sarkar. The second was the damage she did to our political institutions. We owe Nehru a great debt because he built those institutions. Our modern political democracy we owe it to him. But she did a lot of damage to those institutions. Could you elaborate on that little?

During the period she was the Prime Minister, I think she dismissed fifty nine elected governments in states. Now we hardly hear of this. This is partly a reaction to what she had done. She tried to change India’s culture and change our political system. A lot has been written about the emergency and so on. But the enduring damage we don’t realise. Before her, Chief Ministers were a little afraid when a secretary said no sir you can’t do this. And if you tried to do it, the secretary wouldn’t bend very often. Now they just transfer. Look at what Mayawati did. Also after Indira Gandhi the police became a handmaiden of the executive. The police lost its independence. Even the judiciary was damaged. She wanted committed judges. Fortunately the Supreme Court did not succumb to that rot.

“It is tempting to compare crisis-ridden Hastinapur with today’s flailing Indian state,” you write. Could you explain that in some detail?

Before this I wrote this book called The Difficulty of Being Good. I interrogated the Mahabharata in a modern contemporary way. And I realised that the Mahabharata is us, still. The great scholar Sukthankar, the editor of the critical edition of the Mahabharata had once said that the Mahabharata is us. And I had always wondered what he had meant. I realised reading the book that really it’s a story of India. And why I preferred the Mahabharata to the Ramayana is because in the Ramayana, the hero is perfect. The brother of the hero is perfect. The wife of the hero is perfect. Even the villain is perfect. Luckily I had done Sanskrit in College and so I went back to my roots. I went to study in Chicago.

And what did you realise after studying the Mahabharata?

Essentially the Mahabharata is about the corruption of the kshatriya institutions of that time. The way the rulers, the nobles behaved, it clearly upset the author of the Mahabharata or we should say authors, because it was continuously evolved over 400-500years. They were very upset and enraged as today young Indians are enraged by the government. They were enraged by the institutions of these kshatriyas. The sort of the big chested behaviour. The idea that you went to heaven if you died fighting on the battle field. That sort of notion. So most people think Mahabharata is about war, but actually it’s an anti war epic.

So what is the point you are trying to make?

In Mahabharata, Hastinapur is the capital of the kingdom of the Kauravas. The Pandavas have created a new capital at Indraprastha. The point is crisis ridden Hastinapur is somewhat like our crisis ridden institutions of today. People were impatient and they were enraged by what was going on and so they had to wage a war at Kurushetra. And I just hope that we don’t have to do that. We can reform the institutions before we reach that point. That’s the comparison to Kurushetra and Hastinapur that I spoke about.

You were a socialist once?

I was a socialist like all of us when we were in the 20s and 30s. But then we could see that Nehru’s path was leading us to a dead end. Certainly a part of India Unbound is a story of the personal humiliations that I experienced, and on top of that Indira Gandhi’s failures really converted me. When the reforms came in 1991 I had become a libertarian. I really celebrated the reforms. For me that was Diwali and so I began to believe that the story of India rising without the state was a sustainable story. And I began to believe that this was a heroic thing and a laissez faire state was the best state. Back then, in my view the state was a second order phenomenon. Now writing this book partly and looking back over twenty years, I have concluded that state is a first order phenomenon. So I have gone from being a socialist to a libertarian to what I would go back and say is a classical liberal, who really doesn’t believe that laissez faire is the answer, and who does believe that you need the state.

Can you elaborate on that?

You need a limited state and not a minimalist state as Nozick(Robert Nozick, an American political philosopher) would have said. But that limited state must perform. So I have come to realise that the success after 1991 has partly been because there were regulators in those sectors, which rose. The election commissioner, the RBI, the Sebi, these have all contributed. Or even the first TRAI(Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, the telecom regulator) under Justice Sodhi and Zutshi. That first TRAI sent the right signals. If we had left it to the Department of Telecom (DOT) and did not have any regulator things might have been different. DOT wanted to crush the new private companies. So what I am saying is that you need good regulators. You need government as a good umpire. You don’t need government to own Air India. But you need a good civil aviation regulator who will ensure a level playing field for everyone in the market.

You explain in some depth in your book as to why Indian political parties treat voters as victims. One can see that happening all the time and everywhere…

And it also explains why I cannot vote for anybody in 2014. Really as an Indian citizen I have been thinking who will I vote for? Every party treats voters as a victim. They are all parties of grievance. We don’t realise that one third of India is now middle class. This new middle class are tigers. They have just made it. They don’t want to be reminded that they are victims. They are looking for the state to further their rise. And they are looking for good roads, good schools and these things.

But nobody talks about development in India…

Yeah. BJP if you scratch them you know they are talking about 1000 years of Muslim oppression. Congress says you are victim of globalisation and liberalisation. So we will give you free power, free this and free that, NREGA etc. Dalit parties say you are a victim of oppression. OBC parties say you are a victim of upper caste oppression. Nobody is talking about the reform of the institution. Even the Anna Hazare movement was talking about only one Lokpal, which is fine, but it had to be couched in a bigger story.

You critique the Anna movement by saying that they have further undermined politicians and political life. Could you explain that in detail?

They have undermined the politics and political life. It is very easy to do that. When you attack politicians then you are also unwittingly attacking the institution of elections. The good thing is that it has put a fear in the minds of politicians. Whether the Anna Hazare movement fails or succeeds is no longer important. What is important is the legacy that it has woken up the middle class. That won’t go away easily. The question then for a young person today is that the Anna movement may have gone, but what can I do? The answer is start with your neighbourhood. Start with your ward and see what can be done. And that is the local democracy I am talking about. That’s where politics begins and that’s where habits of the heart created. I am so in favour of grass-root democracy, the fact that we should put the power downwards. Also even in the rhetoric of the Anna Hazare movement they talked about the gram sabha, the mohalla sabha, that’s where we get the habits of the heart.

What about Arvind Kejriwal’s decision to enter politics? How do you view that?

Before I get to that let me discuss something that I talk about in my book. In this book I hope for a formation of a new political party along the lines of the erstwhile Swatantra Party. But the agenda of this party is not just economic reform but institutional reform. At the Delhi launch of my book Arivnd Kerjiwal was there. TN Ninan, Chairman of the Business Standard newspaper,was moderating the discussion and he said since both of you are advocating a political party, why don’t you join hands. I said, I admire Kejriwal, but he has got all kinds of crazy people around him, who still think that reforms were a bad India. Also, they never talk about institutional reform. So I am not sure that we could be together. But I said were we would be together is that both of us are tapping into the new middle class, which is impatient, confident, assured and which wants to get rid of corruption. But I feel that we need the hard work of institutional reforms and that street protest is not the answer. I also said I am so glad that Kejriwal is now looking at politics because that is the right route to go.

One of the things that one frequently comes across in your book is that you are hopeful that the politics of India will change in the next few years as more and more people become middle class.

Yes.

But it doesn’t look like…

It doesn’t look like because politics has been left behind. But now they are realising. They have been shaken up because so many of them (the politicians) have gone to jail. Even the language is a little more cautious now.

So you see the kind of chaos that prevails right now will go away?

It is only out of chaos that something happens. As Nietzsche(Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, a German philosopher) said that it is the chaos in the heart that gives birth to a dancing star. I see things positively even though we have been a weak state. But as they say, history is not destiny.

“The trickling down of power has made India more difficult to rule,” you write. Could you explain that in the context of the politics that is currently playing out?

It has made India more difficult to govern. But it remains a very important development because I am in favour of federalism. The best thing about FDI in multi brand retailing is that they have given the states the freedom to decide whether they want foreign investment or not. So imagine an FDI decision is now in the hands of the state. And I think that is wonderful because each state is like a country in India. The state of UP has 180 million people and I have no problem is with the trickling down of power. My problem is that we should be able to have an effective executive at the centre. Today we have a very weak Prime Minister. We need a stronger person in the role. We don’t want an Indira Gandhi, but we want a strong person who can be an institutional reformer.

You hope for the rise of a free market based party like the erstwhile Swatantra Party(a party formed by C Rajagopalachari and NG Ranga in 1959 to oppose the socialist policies of Nehru). Do you see really see that happening?

You have to be lucky to some extent and hope to get a young leader. I don’t know who it will be. But there will be somebody in their thirties and forties. Then the country will rally behind them. The way they rallied behind the Kejriwal, Anna Hazare movement. In one sense the last thing India needs is a another political party. But I also see that I cannot vote for any political party. I see that there is a wing of the Congress which does not like this free power and that entitlement culture and the corruption that is being bred in the Congress. There are people even in the BJP who have faith in the past, but they are not anti-Muslim necessarily. So I think they will come together for a secular political liberal party. Similarly there are people in the regional parties. And this is a good time for a liberal party. Swatantra Party was at the wrong time. They were too early. They were ahead of their time. So if we are lucky we will throw up a leader, but you can’t depend on that. But the hopeful thing is the rise of the middle class which will make the politics change.

(The interview originally appeared on www.firstpost.com. http://www.firstpost.com/india/how-india-grows-at-night-while-the-government-sleeps-469035.html)

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected]