On May 31, 2014, the total outstanding debt of the United States government stood at $17.52 trillion. The debt outstanding has gone up by $7.5 trillion, since the start of the financial crisis in September 2008. On September 30, 2008, the total debt outstanding had stood at $10.02 trillion.

In a normal situation as a country or an institution borrows more, the interest that investors demand tends to go up, as with more borrowing the chance of a default goes up. And given this increase in risk, a higher rate of interest needs to be offered to the investors.

But what has happened in the United States is exactly the opposite.

In September 2008, the average rate of interest that the United States government paid on its outstanding debt was 4.18%. In May 2014, this had fallen to 2.42%.

When the financial crisis broke out money started flowing into the United States, instead of flowing out of it. This was ironical given that the United States was the epicentre of the crisis. A lot of this money was invested in treasury bonds. The United States government issues treasury bonds to finance its fiscal deficit.

As Eswar S Prasad writes in The Dollar Trap—How the US Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance “From September to December 2008, U.S. securities markets had net capital inflows (inflows minus outflows) of half a trillion dollars…This was more than three times the total net inflows into U.S. securities markets in the first eight months of the year. The inflows largely went into government debt securities issued by the U.S. Treasury[i.e. treasury bonds].”

This trend has more or less continued since then. Money has continued to flow into treasury bonds, despite the fact that the outstanding debt of the United States has gone up at an astonishing pace. Between September 2008 and May 2014, the outstanding debt of the United States government went up by 75%.

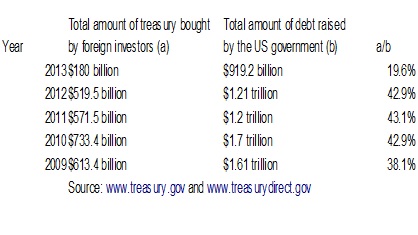

The huge demand for treasury bonds has ensured that the American government can get away by paying a lower rate of interest on the bonds than it had in the past. In fact, foreign countries have continued to invest massive amounts of money into treasury bonds, as can be seen from the table.

Between 2010 and 2012, the foreign countries bought around 43% of the debt issued by the United States government. In 2009, this number was slightly lower at 38.1%.

How do we explain this? As Prasad writes “The reason for this strange outcome is that the crisis has increased the demand for safe financial assets even as the supply of such assets from the rest of the world has shrunk, leaving the U.S. as the main provider.”

Large parts of Europe are in a worse situation than the United States and bonds of only countries like Austria, Germany, France, Netherlands etc, remain worth buying. But these bonds markets do not have the same kind of liquidity (being able to sell or buy a bond quickly) that the American bond market has. The same stands true for Japanese government bonds as well. “The stock of Japanese bonds is massive, but the amount of those bonds that are actively traded is small,” writes Prasad.

Also, there are not enough private sector securities being issued. Estimates made by the International Monetary Fund suggest that issuance of private sector securities globally fell from $3 trillion in 2007 to less than $750 billion in 2012. What has also not helped is the fact that things have changed in the United States as well. Before the crisis hit, bonds issued by the government sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were considered as quasi government bonds. But after the financial mess these companies ended up in, they are no longer regarded as “equivalent to U.S. government debt in terms of safety”.

This explains one part of the puzzle. The foreign investors always have the option of keeping the dollars in their own vaults and not investing them in the United States. But the fact that they are investing means that they have faith that the American government will repay the money it has borrowed.

This “childlike faith of investors” goes against what history tells us. Most governments which end up with too much debt end up defaulting on it. Most countries which took part in the First World War and Second World War resorted to the printing press to pay off their huge debts. Between 1913 and 1950, inflation in France was greater than 13 percent per year, which means prices rose by a factor of 100. Germany had a rate of inflation of 17 percent, leading to prices rising by a factor of 300. The United States and Great Britain had a rate of inflation of around 3 percent per year. While that doesn’t sound much, even that led to prices rising by a factor of three1.

The inflation ensured that the value of the outstanding debt fell to very low levels. John Mauldin, an investment manager, explained this technique in a column he wrote in early 2011. If the Federal Reserve of the United States, the American central bank, printed so much money that the monetary base would go up to 9 quadrillion (one followed by fifteen zeroes) US dollars. In comparison to this the debt of $13 trillion (as it was the point of time the column was written) would be small change or around 0.14 percent of the monetary base2.

In fact, one of the rare occasions in history when a country did not default on its debt either by simply stopping to repay it or through inflation, was when Great Britain repaid its debt in the 19th century. The country had borrowed a lot to finance its war with the American revolutionaries and then the many wars with France in the Napoleonic era. The public debt of Great Britain was close to 100 percent of the GDP in the early 1770s. It rose to 200 percent of the GDP by the 1810s. It would take a century of budget surpluses run by the government for the level of debt to come down to a more manageable level of 30 percent of GDP. Budget surplus is a situation where the revenues of a government are greater than its expenditure3.

The point being that countries more often than not default on their debt once it gets to unmanageable levels. But foreign investors in treasury bonds who now own around $5.95 trillion worth of treasury bonds, did not seem to believe so, at least during the period 2009-2012. Why was that the case? One reason stems from the fact nearly $4.97 trillion worth of treasury bonds are intra-governmental holdings. These are investments made by various arms of the government in treasury bonds. This primarily includes social security trust funds. Over and above this around $4.5 trillion worth of treasury bonds are held by pension funds, mutual funds, financial institutions, state and local governments and households.

Hence, any hint of a default by the U.S. government is not going to go well with these set of investors. Also, a significant portion of this money belongs to retired people and those close to retirement. As Prasad puts it “Domestic holders of Treasury debt are potent voting and lobbying blocs. Older voters tend to have a high propensity to vote. Moreover, many of them live in crucial swing states like Florida and have a disproportionate bearing on the outcomes of U.S. presidential elections. Insurance companies as well as state and local governments would be clearly unhappy about an erosion of the value of their holdings. These groups have a lot of clout in Washington.”

Nevertheless, the United States government may decide to default on the part of its outstanding debt owned by the foreigners. There are two reasons why it is unlikely to do this, the foreign investors felt.

The United States government puts out a lot of data regarding the ownership of its treasury bonds. “But that information is based on surveys and other reporting tools, rather on registration of ownership or other direct tracking of bonds’ final ownership. The lack of definitive information about ultimate ownership of Treasury securities makes it technically very difficult for the U.S. government to selectively default on the portion of debt owned by foreigners,” writes Prasad.

Over and above this, the U.S. government is not legally allowed to discriminate between investors.

This explains to a large extent why foreign investors kept investing money in treasury bonds. But that changed in 2013. In 2013, the foreign countries bought only 19.6% of the treasury bonds sold in comparison to 43% they had bought between 2010 and 2012.

So, have the foreign financiers of America’s budget deficit started to get worried. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations “When national debts have once been accumulated to a certain degree, there is scarce, I believe, a single instance of their having been fairly and completely paid. The liberation of the public revenue, if it has been brought about at all, has always been brought about by a bankruptcy; sometimes by an avowed one, but always by a real one, though frequently by a pretended payment [i.e., payment in an inflated or depreciated monetary unit].”

Have foreign countries investing in treasury bonds come around to this conclusion? Or what happened in 2013, will be reversed in 2014? There are no easy answers to these questions.

For a country like China which holds treasury bonds worth $1.27 trillion it doesn’t make sense to wake up one day and start selling these bonds. This will lead to falling prices and will hurt China also with the value of its foreign exchange reserves going down. As James Rickards writes in The Death of Money “Chinese leaders realize that they have overinvested in U.S. -dollar-denominated assets[which includes the treasury bonds]l they also know they cannot divest those assets quickly.”

It is easy to see that the United States government has gone overboard when it comes to borrowing, but whether that will lead to foreign investors staying away from treasury bonds in the future, remains difficult to predict. As Prasad puts it “It is possible that we are on a sandpile that is just a few grains away from collapse. The dollar trap might one day end in a dollar crash. For all its logical allure, however, this scenario is not easy to lay out in a convincing way.”

Author Satyajit Das summarizes the situation well when he says “Former French Finance Minister Valery Giscard d’Estaing used the term “exorbitant privilege” to describe American advantages deriving from the role of the dollar as a reserve currency and its central role in global trade. That privilege now is “extortionate.”” This extortionate privilege comes from the fact that “if not the dollar, and if not U.S. treasury debt, then what?” As things stand now, there is really not alternative to the dollar. The collapse of the dollar would also mean the collapse of the international financial system as it stands today. As James Rickards writes in The Death of Money “If confidence in the dollar is lost, no other currency stands to take its place as the world’s reserve currency…If it fails, the entire system fails with it, since the dollar and the system are one and the same.”

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])

The article appeared originally in the July 2014 issue of the Wealth Insight magazine

1T. Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century(Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014)

2 Mauldin, J. 2011. Inflation and Hyperinflation. March 10. Available at http://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/inflation-and-hyperinflation, Downloaded on June 23, 2012

3T. Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century(Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014)