In response to the last column a reader wrote in on Twitter saying “shudder to think what would happen [to the stock market] if FIIs[foreign institutional investors] packed their bags and left.” Since the start of the financial crisis in September 2008 and up to October 2014, the FIIs have made net purchases (gross purchase minus gross sales of stocks) close to Rs 2.76 lakh crore in the Indian stock market. During the same period, the domestic institutional investors(DIIs) made net sales of Rs 95,219 crore.

The FIIs have continued to bring in money even during the course of this year. Between January and November 10, 2014, they had made net purchases of stocks worth Rs 65,751.25 crore. During the same period, the DIIs had made net sales of stocks worth Rs 30,136.32 crore.

Over and above this, the FIIs own around 26% of the BSE 100 stocks. Deepak Parekh in a recent speech estimated that after excluding promoter shareholding and the retail segment, which do not have too much liquidity, FIIs dominate close to 70% of the stock market.

What all these numbers clearly tell us is that the foreign investors run the Indian stock market. But that we had already established in the last column. In this column we will try and address the question as to what will happen if foreign investors packed their bags and left? The simple answer is that the stock market will fall and will fall big time. The foreign investors control 70% of the stock market and if they sell out, chances are there won’t be enough buyers in the market.

Nevertheless, the foreign investors also know this, so will they ever try getting out of the Indian stock market, lock, stock and barrel? This is where things get a little tricky.

Let’s try and get deeper into this through a slightly similar situation in a different financial market. Over the years, the United States(US) government has spent much more than it has earned and has financed the difference through borrowing. As on November 7, 2014, the total borrowing of the United States government stood at $ 17.94 trillion dollars. The US government borrows this money by selling financial securities known as treasury bonds.

A little over $6 trillion of treasury bonds are held by foreign countries. Within this, China holds bonds worth $1.27 trillion and Japan holds bonds worth $1.23 trillion. Even though the difference in the total amount of treasury bonds held by China and Japan is not much, China is clearly the more important country in this equation.

Why is that the case? James Rickards explains this in great detail in Currency Wars—The Making of the Next Financial Crisis. The buying of treasury bonds by the Japanese is not as centralized as is the case with China, where the People’s Bank of China, the Chinese central bank, does the bulk of the buying. In the Japanese case the buying is spread among the Bank of Japan, which is the Japanese central bank, and other institutions like the big banks and pension funds.

The United States realizes the importance of China in the entire equation. Right till June 2011, China bought American treasury bonds through primary dealers, which were essentially big banks dealing directly with the Federal Reserve of the United States. But since then things have changed. The treasury department of the US (or what we call finance ministry in India) has given the People’s Bank of China, a direct computer link to its bond auction system.

Also, there is a great fear of what will happen if the Chinese ever decide to get out of US treasury bonds, lock, stock and barrel. It will lead to a contagion where many investors will try getting out of the treasury bonds at the same time, leading to a fall in their price.

A fall in price would mean that the returns on these bonds will go up, as the US government will continue paying the same interest on these bonds as it had in the past. Higher returns on the treasury bonds will mean that the interest rates on bank deposits and loans will also have to go up.

This can lead to a global financial crisis of the kind we saw breaking out in September 2008. Nevertheless, the question is will China wake up one fine day and start selling out of US government bonds? For a country like China, which holds treasury bonds worth $1.27 trillion, it does not make sense to wake up one day and start selling these bonds. This as explained earlier will lead to a fall in bond prices, which will hurt China as the value of its investment will go down. China has invested the foreign exchange that it earns through exports, in treasury bonds.

As on September 30, 2014, the Chinese foreign-exchange reserves stood at close to $3.89 trillion. Hence, nearly one third of Chinese foreign-exchange reserves are invested in US treasury bonds. Given this, it is highly unlikely that China will jeopardise the value of these foreign-exchange reserves by suddenly selling out of treasury bonds.

What China has done instead is that since November last year its investment in US treasury bonds has been limited to around $1.27 trillion. Also, some threats work best when they are not executed.

Hence, when it comes to the Chinese and their investment in treasury bonds, the situation is best expressed by the Hotel California song, sung by The Eagles: “You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

Now let’s get back to the FIIs and their investment in the Indian stock market. Isn’t their situation similar to the Chinese investment in US treasury bonds? If they ever try to exit the Indian stock market lock, stock and barrel, it is worth remembering that they control nearly 70% of the market. When foreign investors decide to sell there won’t be enough buyers in the market. Hence, stock prices will fall big time, leading to foreign investors having to face further losses on the massive investments that they have made over the years.

Given this, are the Chinese in the US and foreign investors in India in a similar situation? Does the Hotel California song apply to foreign investors in India as well? Prima facie that seems to be the case. But there is one essential difference that we are ignoring here.

Nearly one third of Chinese foreign-exchange reserves are invested in US treasury bonds. Hence, China has a significant stake in the US treasury bond market. The same cannot be said about foreign investors in India’s stock market, at least when we consider them as a whole.

As Deepak Parekh said in a recent speech “India ranks among the top 10 global equity markets in terms of market cap. However, India accounts for just 2.4% of the global market capitalization of US $64 trillion.” Given this, in the global scheme of things for foreign investors, India does not really matter much.

Hence, if a sufficient number of them feel that they need to exit the Indian stock market, they will do that, even if it means that they have to face losses in the process. As mentioned earlier, in the global scheme of things, these losses won’t matter. Also, a lot of money brought into India by the FIIs has been due to the “easy money” policy run by the Federal Reserve of the United States and other Western central banks.

These central banks have printed money to maintain interest rates at low levels. The foreign investors have borrowed money at low interest rates and invested in the Indian stock market. Once these interest rates start to go up, it may no longer make sense for them to stay invested in India. Of course, it is very difficult to predict when will that happen.

Nevertheless, it is worth remembering what Steven Pinker writes in his new book The Sense of Style—The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century: “It’s hard to know the truth, that the world doesn’t just reveal itself to us, that we understand the world through our theories and constructs, which are not pictures but abstract propositions.”

And whatever I have written in today’s column is my abstract proposition. Hence, the question still remains: Will foreign investors ever sell out of the Indian stock market, lock, stock and barrel?

treasury bonds

The extortionate privilege of the dollar

On May 31, 2014, the total outstanding debt of the United States government stood at $17.52 trillion. The debt outstanding has gone up by $7.5 trillion, since the start of the financial crisis in September 2008. On September 30, 2008, the total debt outstanding had stood at $10.02 trillion.

In a normal situation as a country or an institution borrows more, the interest that investors demand tends to go up, as with more borrowing the chance of a default goes up. And given this increase in risk, a higher rate of interest needs to be offered to the investors.

But what has happened in the United States is exactly the opposite.

In September 2008, the average rate of interest that the United States government paid on its outstanding debt was 4.18%. In May 2014, this had fallen to 2.42%.

When the financial crisis broke out money started flowing into the United States, instead of flowing out of it. This was ironical given that the United States was the epicentre of the crisis. A lot of this money was invested in treasury bonds. The United States government issues treasury bonds to finance its fiscal deficit.

As Eswar S Prasad writes in The Dollar Trap—How the US Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance “From September to December 2008, U.S. securities markets had net capital inflows (inflows minus outflows) of half a trillion dollars…This was more than three times the total net inflows into U.S. securities markets in the first eight months of the year. The inflows largely went into government debt securities issued by the U.S. Treasury[i.e. treasury bonds].”

This trend has more or less continued since then. Money has continued to flow into treasury bonds, despite the fact that the outstanding debt of the United States has gone up at an astonishing pace. Between September 2008 and May 2014, the outstanding debt of the United States government went up by 75%.

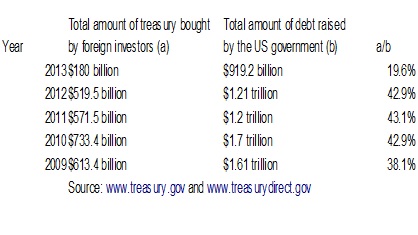

The huge demand for treasury bonds has ensured that the American government can get away by paying a lower rate of interest on the bonds than it had in the past. In fact, foreign countries have continued to invest massive amounts of money into treasury bonds, as can be seen from the table.

Between 2010 and 2012, the foreign countries bought around 43% of the debt issued by the United States government. In 2009, this number was slightly lower at 38.1%.

How do we explain this? As Prasad writes “The reason for this strange outcome is that the crisis has increased the demand for safe financial assets even as the supply of such assets from the rest of the world has shrunk, leaving the U.S. as the main provider.”

Large parts of Europe are in a worse situation than the United States and bonds of only countries like Austria, Germany, France, Netherlands etc, remain worth buying. But these bonds markets do not have the same kind of liquidity (being able to sell or buy a bond quickly) that the American bond market has. The same stands true for Japanese government bonds as well. “The stock of Japanese bonds is massive, but the amount of those bonds that are actively traded is small,” writes Prasad.

Also, there are not enough private sector securities being issued. Estimates made by the International Monetary Fund suggest that issuance of private sector securities globally fell from $3 trillion in 2007 to less than $750 billion in 2012. What has also not helped is the fact that things have changed in the United States as well. Before the crisis hit, bonds issued by the government sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were considered as quasi government bonds. But after the financial mess these companies ended up in, they are no longer regarded as “equivalent to U.S. government debt in terms of safety”.

This explains one part of the puzzle. The foreign investors always have the option of keeping the dollars in their own vaults and not investing them in the United States. But the fact that they are investing means that they have faith that the American government will repay the money it has borrowed.

This “childlike faith of investors” goes against what history tells us. Most governments which end up with too much debt end up defaulting on it. Most countries which took part in the First World War and Second World War resorted to the printing press to pay off their huge debts. Between 1913 and 1950, inflation in France was greater than 13 percent per year, which means prices rose by a factor of 100. Germany had a rate of inflation of 17 percent, leading to prices rising by a factor of 300. The United States and Great Britain had a rate of inflation of around 3 percent per year. While that doesn’t sound much, even that led to prices rising by a factor of three1.

The inflation ensured that the value of the outstanding debt fell to very low levels. John Mauldin, an investment manager, explained this technique in a column he wrote in early 2011. If the Federal Reserve of the United States, the American central bank, printed so much money that the monetary base would go up to 9 quadrillion (one followed by fifteen zeroes) US dollars. In comparison to this the debt of $13 trillion (as it was the point of time the column was written) would be small change or around 0.14 percent of the monetary base2.

In fact, one of the rare occasions in history when a country did not default on its debt either by simply stopping to repay it or through inflation, was when Great Britain repaid its debt in the 19th century. The country had borrowed a lot to finance its war with the American revolutionaries and then the many wars with France in the Napoleonic era. The public debt of Great Britain was close to 100 percent of the GDP in the early 1770s. It rose to 200 percent of the GDP by the 1810s. It would take a century of budget surpluses run by the government for the level of debt to come down to a more manageable level of 30 percent of GDP. Budget surplus is a situation where the revenues of a government are greater than its expenditure3.

The point being that countries more often than not default on their debt once it gets to unmanageable levels. But foreign investors in treasury bonds who now own around $5.95 trillion worth of treasury bonds, did not seem to believe so, at least during the period 2009-2012. Why was that the case? One reason stems from the fact nearly $4.97 trillion worth of treasury bonds are intra-governmental holdings. These are investments made by various arms of the government in treasury bonds. This primarily includes social security trust funds. Over and above this around $4.5 trillion worth of treasury bonds are held by pension funds, mutual funds, financial institutions, state and local governments and households.

Hence, any hint of a default by the U.S. government is not going to go well with these set of investors. Also, a significant portion of this money belongs to retired people and those close to retirement. As Prasad puts it “Domestic holders of Treasury debt are potent voting and lobbying blocs. Older voters tend to have a high propensity to vote. Moreover, many of them live in crucial swing states like Florida and have a disproportionate bearing on the outcomes of U.S. presidential elections. Insurance companies as well as state and local governments would be clearly unhappy about an erosion of the value of their holdings. These groups have a lot of clout in Washington.”

Nevertheless, the United States government may decide to default on the part of its outstanding debt owned by the foreigners. There are two reasons why it is unlikely to do this, the foreign investors felt.

The United States government puts out a lot of data regarding the ownership of its treasury bonds. “But that information is based on surveys and other reporting tools, rather on registration of ownership or other direct tracking of bonds’ final ownership. The lack of definitive information about ultimate ownership of Treasury securities makes it technically very difficult for the U.S. government to selectively default on the portion of debt owned by foreigners,” writes Prasad.

Over and above this, the U.S. government is not legally allowed to discriminate between investors.

This explains to a large extent why foreign investors kept investing money in treasury bonds. But that changed in 2013. In 2013, the foreign countries bought only 19.6% of the treasury bonds sold in comparison to 43% they had bought between 2010 and 2012.

So, have the foreign financiers of America’s budget deficit started to get worried. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations “When national debts have once been accumulated to a certain degree, there is scarce, I believe, a single instance of their having been fairly and completely paid. The liberation of the public revenue, if it has been brought about at all, has always been brought about by a bankruptcy; sometimes by an avowed one, but always by a real one, though frequently by a pretended payment [i.e., payment in an inflated or depreciated monetary unit].”

Have foreign countries investing in treasury bonds come around to this conclusion? Or what happened in 2013, will be reversed in 2014? There are no easy answers to these questions.

For a country like China which holds treasury bonds worth $1.27 trillion it doesn’t make sense to wake up one day and start selling these bonds. This will lead to falling prices and will hurt China also with the value of its foreign exchange reserves going down. As James Rickards writes in The Death of Money “Chinese leaders realize that they have overinvested in U.S. -dollar-denominated assets[which includes the treasury bonds]l they also know they cannot divest those assets quickly.”

It is easy to see that the United States government has gone overboard when it comes to borrowing, but whether that will lead to foreign investors staying away from treasury bonds in the future, remains difficult to predict. As Prasad puts it “It is possible that we are on a sandpile that is just a few grains away from collapse. The dollar trap might one day end in a dollar crash. For all its logical allure, however, this scenario is not easy to lay out in a convincing way.”

Author Satyajit Das summarizes the situation well when he says “Former French Finance Minister Valery Giscard d’Estaing used the term “exorbitant privilege” to describe American advantages deriving from the role of the dollar as a reserve currency and its central role in global trade. That privilege now is “extortionate.”” This extortionate privilege comes from the fact that “if not the dollar, and if not U.S. treasury debt, then what?” As things stand now, there is really not alternative to the dollar. The collapse of the dollar would also mean the collapse of the international financial system as it stands today. As James Rickards writes in The Death of Money “If confidence in the dollar is lost, no other currency stands to take its place as the world’s reserve currency…If it fails, the entire system fails with it, since the dollar and the system are one and the same.”

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])

The article appeared originally in the July 2014 issue of the Wealth Insight magazine

1T. Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century(Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014)

2 Mauldin, J. 2011. Inflation and Hyperinflation. March 10. Available at http://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/inflation-and-hyperinflation, Downloaded on June 23, 2012

3T. Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century(Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014)