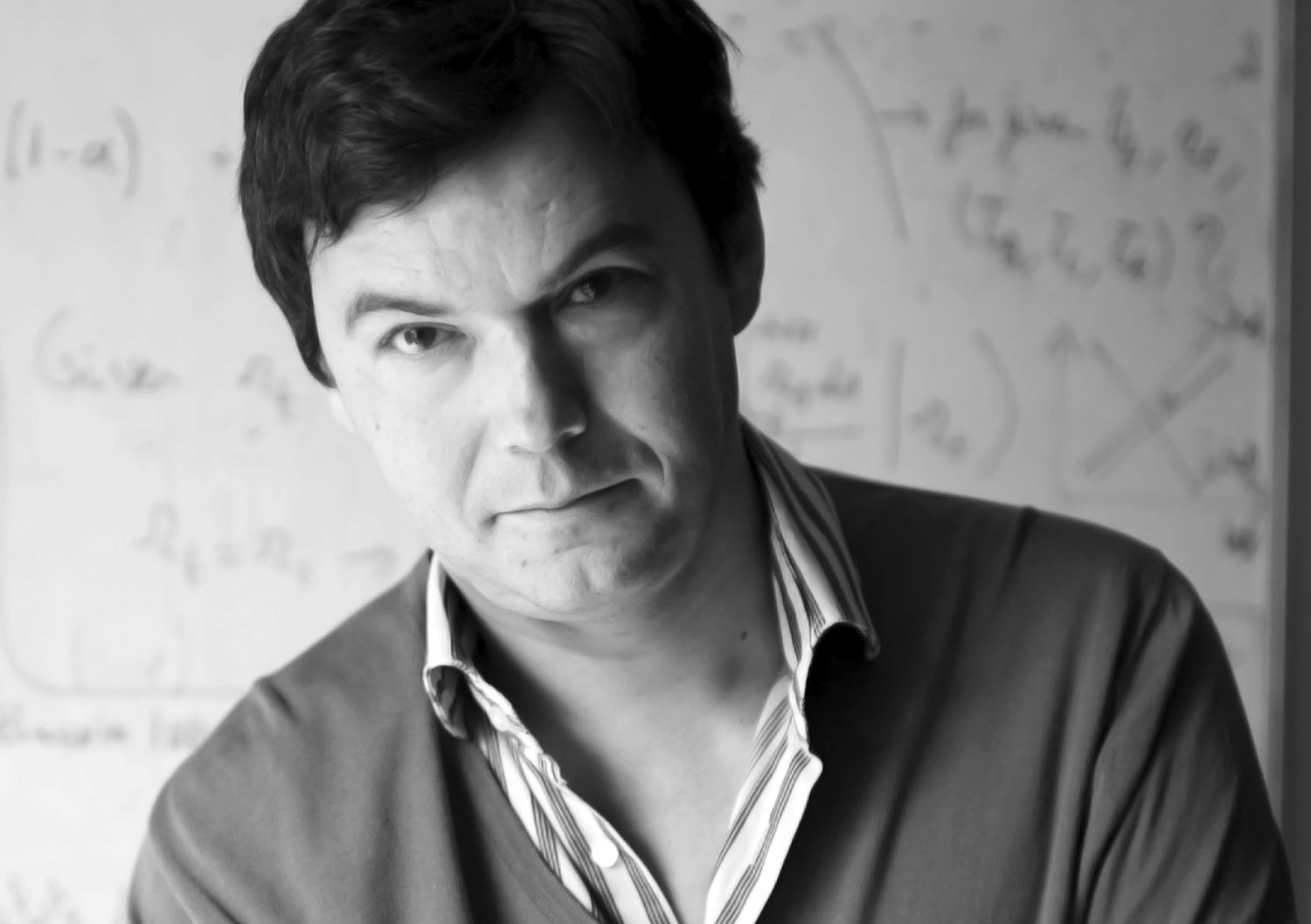

Thomas Piketty, a French economist, has taken the world by storm. His book Capital in the Twenty-First Century has been the second bestselling book on Amazon.com for a while now. Originally written in French, the book was translated into English and released a few months back in the United States.

Piketty’s Capital is not like some of the recent popular books in economics like Freakonomics or The Undercover Economist. It is a book running into 577 pages (if we ignore the notes running into nearly 80 pages) and is not exactly a bedtime read.

My idea is not to summarize the book in this column. That would be doing grave injustice to the book. Nevertheless I wanted to discuss an important point that the book makes.

A major but not so well discussed reason behind the financial crisis was the increasing inequality in the United States. Piketty discusses this in great detail in Capital.

The top 10% of the American population earned a little more than 50% of the national income on the eve of the financial crisis and then again in the early 2010s. In fact, if we look at income without capital gains, the top 10% earned more than 46% of the national income in 2010, which is already significantly higher than the income level attained in 2007, before the financial crisis started. The trend continued in 2011-2012 as well. In 1976, the top 10% of households earned around 33% of the national income.

The situation becomes even more grim when we look at the top 1% of the population. The top 1% of the households accounted for only 7.9% of total American wealth in 1976. This would grow to 23.5% of the income by 2007. This was because the incomes of those in the top echelons was growing at a much faster rate. The rate of growth of income for the period for those in the top 1% was at 4.4% per year. The remaining 99% grew at 0.6% per year.

A major reason for this inequality has been the pace at which the salaries of the top management of American companies have gone up. As Piketty writes“We’ve gone from a society of rentiers to a society of managers…Top managers[who Piketty calls supermanagers] have the power to set their own remuneration…or by corporate compensation committees whose members usually earn comparable salaries…in some cases without limit and in many cases without any clear relation to their individual productivity, which in any case is very difficult to estimate in a large organization.” This phenomenon was seen mainly in the United States, writes Piketty. But it was seen to a lesser extent in Great Britain and other English speaking developed countries in both the financial as well as non financial sectors.

In fact, Piketty even calls this phenomenon of senior managers being paid very high salaries as a form of “meritocratic extremism” or the need of modern societies, in particular the American society, to reward certain individuals deemed to be as “winners”. Interestingly, research shows that these winners got paid for luck more often than not. It shows that salaries went up most rapidly when sales and profits went up due to external reasons.

The solution to this increasing inequality of income was to some extent more education. But that is something that would take serious implementation and at the same time results wouldn’t have come overnight. How does a politician who has to go back to the electorate every few years deal with this? He needs to plan and think for the long run. But at the same time he needs to ensure that his voters keep electing him. If the voters don’t keep electing him in the short run there is nothing much he can do to improve things in the long run.

This is precisely what happened in the United States. Politicians addressed the issue of inequality by making sure that easier credit was accessible to their voters. Raghuram Rajan, currently the governor of the Reserve Bank of India, explains this very well in his award winning book Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy: “Since the early 1980s, the most seductive answer has been easier credit. In some ways, it is the path of least resistance…Politicians love to have banks expand housing credit, for all credit achieves many goals at the same time. It pushes up house prices, making households feel wealthier, and allows them to finance more consumption. It creates more profits and jobs in the financial sector as well as in real estate brokerage and housing construction. And everything is safe—as safe as houses—at least for a while.”

Hence, the palliative proposed by politicians for the increasing income inequality in America was easy credit. As Michael Lewis writes in The Big Short – A True Story “How do you make poor people feel wealthy when wages are stagnant? You give them cheap loans.”

While, the government and the politicians worked towards making borrowing easier, there is another point that needs to be made here. As income levels stagnated at lower levels, a large section of the population had to resort to taking on debt and this contributed to the financial instability of the United States. As Piketty writes in Capital “One consequences of increasing inequality was virtual stagnation of the purchasing power of the lower and middle classes…which inevitably made it more likely that modest households would take on debt, especially since unscrupulous banks and financial intermediaries….eager to earn good yields on enormous savings injected into the system by the well-to-do, offered credit on increasingly generous terms.”

So, it worked both ways. The government made it easier to borrow and the people were more than willing to borrow. As author Satyajit Das puts it “Borrowing became a substitute for rising incomes.”

This wasn’t surprising given that the minimum wage in the United States when measured in terms of purchasing power reached its maximum level in 1969. At that point of time the wage stood at $1.60 an hour or $10.10 in 2013 dollars, taking into account the inflation between 1968 and 2013. At the beginning of 2013, it was at $7.25 an hour, lower than that in 1969, in purchasing power terms.

The easy money strategy that has been followed in the aftermath of the financial crisis has again worked led to increasing inequality. The American stock market has rallied by more than 150% in the last five years and this has benefited the richest Americans.

In the five year bull run, the stock market generated a paper wealth of more than $13.5 trillion. In fact, in 2013, the market value of listed stocks in the United States went up by $4 trillion. This benefited the top 10% of Americans who own 80% of the shares listed on stock exchanges.

A similar thing happened in the United Kingdom, where the Bank of England admitted in 2012 that its quantitative easing program boosted the value of stocks and bonds by 25% or about $970 billion. Almost 40% of these gains went to the richest 5% of the British households.

Interestingly, the salaries of CEOs in the United States have continued to go up, even after the financial crisis. If one considers the Fortune 500 companies, the average CEOs salary is 204 times that of their rank and file workers. This disparity has gone by 20% since 2009.

At the same time, the income of the median American household fell to $51,404 in February 2013. This was 5.6% lower than what it was in June 2009. Further, the average income of the poorest 20% of the Americans has fallen by 8% since 2009. Given this, more than 100 million Americans are receiving some form of support from the government.

In fact new research carried out by Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty reveals that between 2009 and 2012, the top 1% of income earners in the United States enjoyed a real income growth of 31%. Income for the bottom 90% of the earners shrank.

The point being that the Western world does not seem to have learnt from its past mistakes. As George Akerlof and Paul Romer wrote in a research paper titled Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit, “If we learn from experience, history need not repeat itself.”If only that were the case!

Note: Not all data has been sourced from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Some numbers have been sourced from Raghuram Rajan’s Fault Lines.

The article originally appeared in the June 2014 edition of the Wealth Insight magazine

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])