A small cottage industry has emerged around trying to explain why Donald Trump won the US Presidential elections and is now set to become the 45th President of the United States, in January 2017.

In this column, I will not try and explain why Trump won, but something a little more than that. Hence, the headline to that extent is misleading.

The mainstream media in the United States is primarily based out of Washington and New York, which are on the east coast. Given this, we are now being told, they were not in touch with the realities of working class Americans in middle and rural America.

And it is these working-class Americans who ultimately voted for Trump. At least, this is the narrative that is emerging now, to explain why Trump won. Even if this post-facto narrative that is now emerging, is true, the Americans who voted for Trump did so for the wrong reason. Allow me to explain.

During the heydays of the manufacturing in the United States, the factories were based out throughout the large parts of middle America. Gradually, these factories have shut down and jobs have been lost. The conventional narrative is that these jobs have been outsourced to China, where its way cheaper to manufacture stuff that was earlier being manufactured in the United States.

This loss of jobs has impacted the sense of self of many Americans. As Ryan Avent writes in his book The Wealth of Humans—Work and its Absence in the Twenty-First Century: “Work is not just the means by which we obtain the resources needed to put food on the table. It is also a source of personal identity. It helps give structure to our days and our lives. It offers the possibility of personal fulfilment that comes from being of use to others, and it is a critical part of the glue that holds society together and smoothes its operation.”

Hence, those who have lost jobs over the last few decades, think the Chinese and the immigrants are to be blamed for it. In fact, this is one of the major reasons being offered by those analysing Trump’s success. We are now being told that Trump managed to tap into this frustration of middle America, of jobs that had been lost and so and so forth. Or as Donald Trump put it: “We will make America great again”.

But the figures do not reflect this. As economist Michael Hicks writes in a research paper titled The Myth and Reality of Manufacturing in America: “Almost 88 percent of job losses in manufacturing in recent years can be attributable to productivity growth, and the long-term changes to manufacturing employment are mostly linked to the productivity of American factories.”

What does this mean in simple English? It essentially means that an average American worker is producing more stuff while working in a factory than he did in the past. And this is because of the advances made in automation and information technology. This has led to the average worker producing more. It has also led to the need for fewer factories carrying out manufacturing

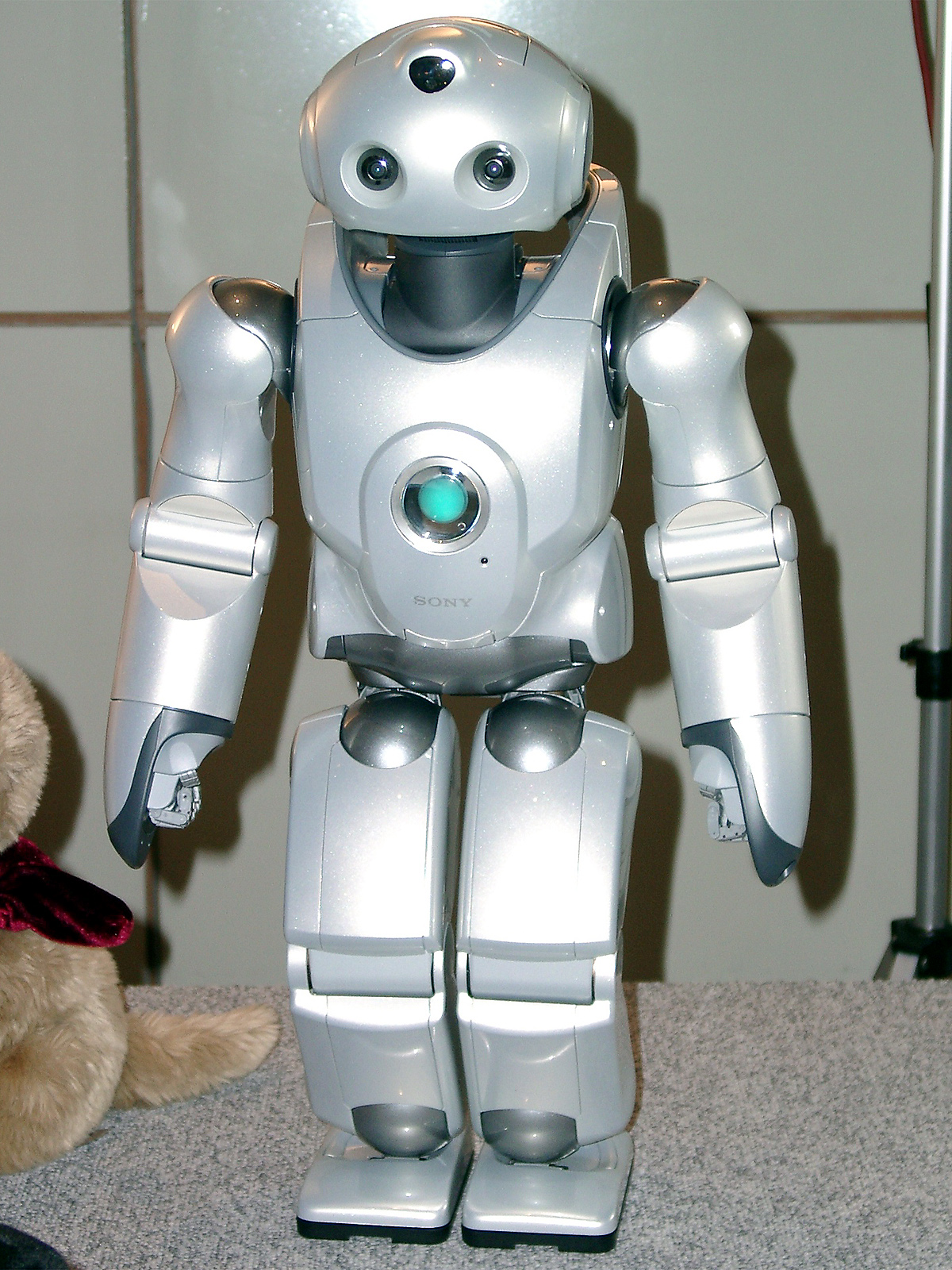

As Hicks puts it: “Had we kept 2000-levels of productivity and applied them to 2010-levels of production, we would have required 20.9 million manufacturing workers. Instead, we employed only 12.1 million.” Hence, American jobs have not been lost to China, nor have they been taken over by immigrants willing to work at lower salaries. They have essentially been lost to better robots.

But as the old saying goes “perception is reality”. The average white American living in middle America thinks that the Chinese and immigrants have taken over his jobs. He can come to that conclusion by driving around his area and seeing all the factories that used to manufacture stuff, now shut. He can see localities and areas which were once burgeoning with people, now having been abandoned. To him this is the reality.

The availability effect is at work here. Nobel Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman defines the availability effect as the “ease with which instances come to mind”. Hence, an average American looks at the scene around him and thinks that the Chinese have taken away his jobs.

This is perception of the reality. This is an average American’s reality. And this has helped Trump win. Or so we are being now told.

The column originally appeared in Bangalore Mirror on November 16, 2016