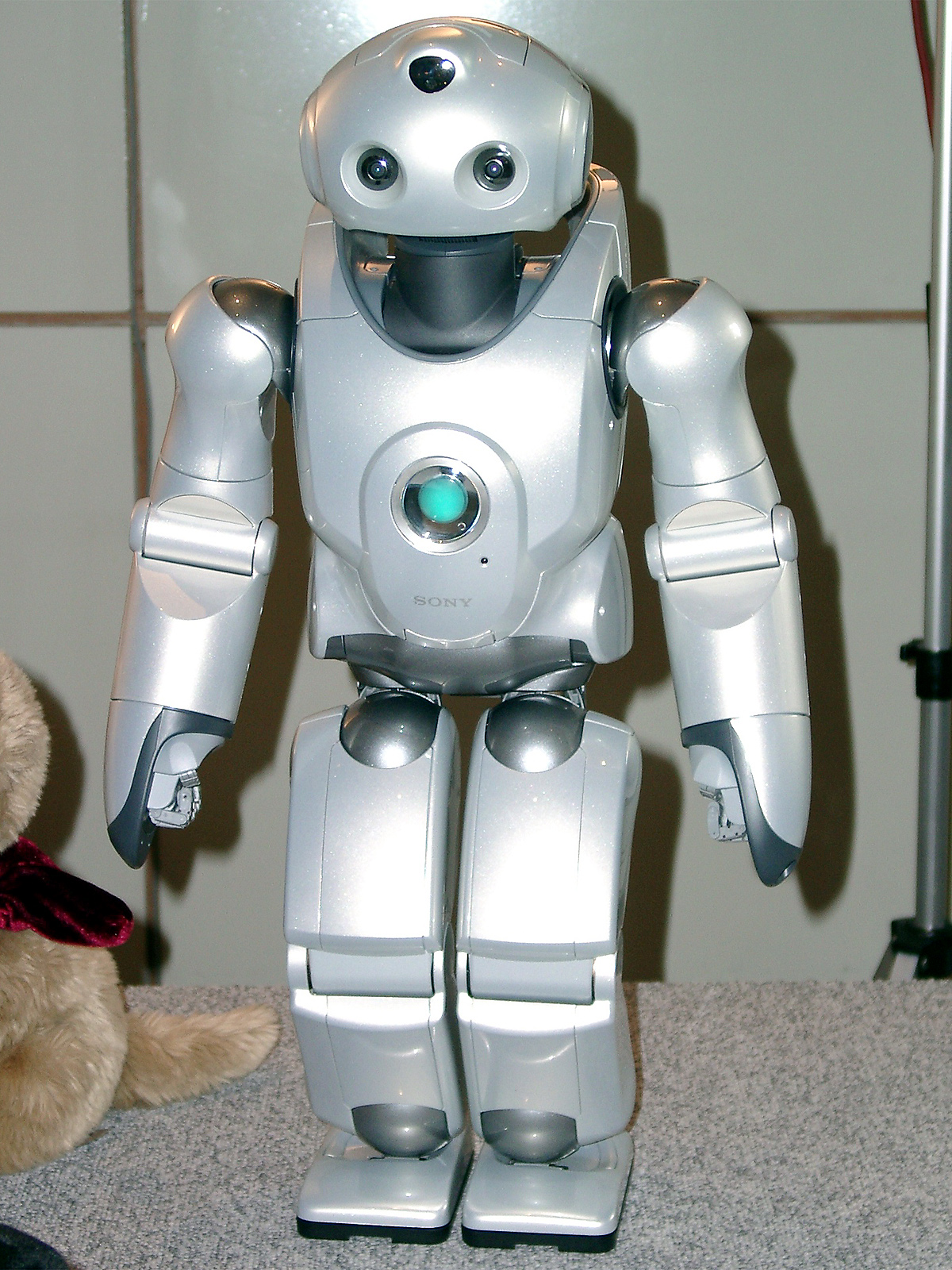

In the recent past, there have been a spate of predictions about robots taking over human jobs. One such prediction was made on October 3, 2016, by the World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, when he said in a speech: “Research based on World Bank data has predicted that the proportion of jobs threatened by automation in India is 69 percent, 77 percent in China and as high as 85 percent in Ethiopia.”[i]

As per predictions being made, it is not only jobs in the developing countries that are at risk. As Rutger Bergman writes in Utopia for Realists: “Scholars at Oxford University estimate that no less than 47 per cent of all American jobs and 54 per cent of those in Europe are at the high risk of being usurped by machines. And not in a hundred years or so, but in next twenty years.” He then quotes a New York university professor as saying: “The only real difference between enthusiasts and skeptics is a time frame.”[ii]

I have view which is different from robots destroying human jobs and I wrote about it in late January 2017. The fear of robots or automation destroying human jobs is not a new one and has been around for a while. So, what is it that makes this fear so believable this time around?

As Yuval Noah Harari writes in Homo Deus—A Brief History of Tomorrow: “This is not an entirely new question. Ever since the Industrial Revolution erupted, people feared that mechanisation [which is what robots are after all about] might cause mass unemployment. This never happened, because as old professions became obsolete, new professions evolved, and there was always something humans could do better than machines. Yet this is not a law of nature and nothing guarantees it will continue to be like that in the future.”[iii]

The question is: What has changed this time around?

Human beings essentially have two kinds of abilities: a) physical ability b) cognitive abilities i.e., the ability to think, understand, reason, analyse, remember, etc. As Harari writes: “As long as machines competed with us merely in physical abilities, you could always find cognitive tasks that humans do better. So machines took over purely manual jobs, while humans focussed on jobs requiring at least some cognitive skills. Yet what will happen once algorithms outperform us in remembering, analysing and recognising patterns?”

And given this, robots will takeover human jobs is the conclusion being drawn. This conclusion has one basic problem—it assumes that human beings will sit around doing nothing and let robots take over their jobs. Now that is a very simplistic thing to believe in. Hence, if and when, it seems likely that robots are really look like taking over human jobs, it is stupid to assume that the governments will sit around doing nothing. There will be huge pressure on them to react and make it difficult for companies to replace human beings with robots.

Over and above this, governments will lose out on tax. When an individual works, he earns an income and then pays an income tax on it to the government. Income tax is a direct tax. Over and above this, in India, when he spends this money, he pays other kind of other taxes, which are largely indirect taxes, like excise duty, service tax, etc. A similar structure works all over the world.

Now let’s say this individual paying taxes gets replaced by a robot. So, the government does not get the income tax that it was getting in the past. Over and above this, the individual who has lost his job, will not spend as much as he was in the past. He will go slow on spending in order to ensure that his savings last for a longer period of time, or at least until he finds another job. If a substantial number of individuals lose their jobs to robots, in this scenario, the government will lose out on a portion of indirect taxes that it was earning earlier. It will also lose out on direct taxes.

So, what is the way out of this?

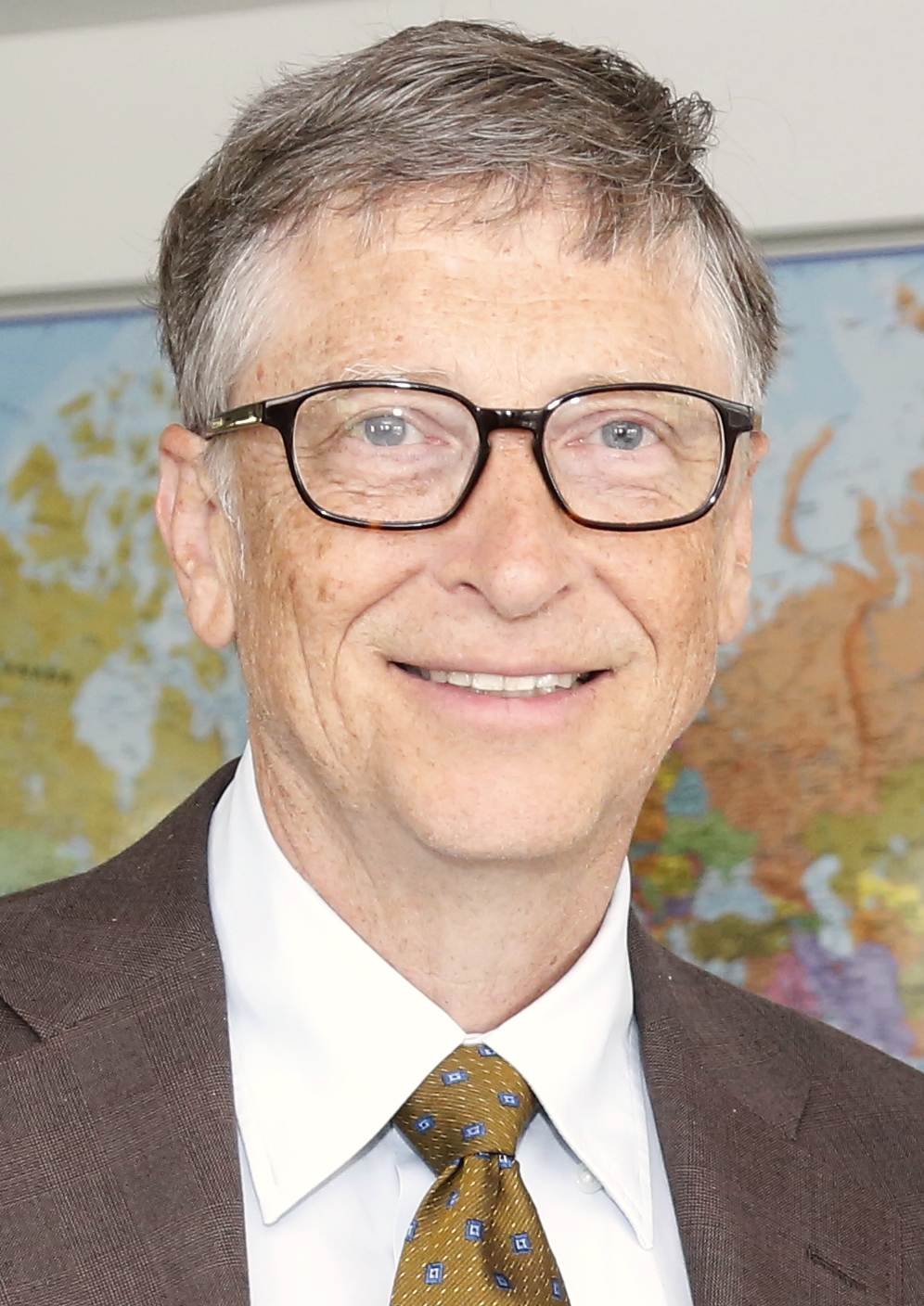

In a recent interview to Quartz.com, Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft, said: “Certainly there will be taxes that relate to automation. Right now, the human worker who does, say, $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed and you get income tax, social security tax, all those things. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think that we’d tax the robot at a similar level.”

Basically, taxing the robot means, taxing the company which owns that robot. And how will this help? It will help the government to finance other jobs. As Gates put it: “And what the world wants is to take this opportunity to make all the goods and services we have today, and free up labor, let us do a better job of reaching out to the elderly, having smaller class sizes, helping kids with special needs. You know, all of those are things where human empathy and understanding are still very, very unique. And we still deal with an immense shortage of people to help out there… So if you can take the labor that used to do the thing automation replaces, and financially and training-wise and fulfillment-wise have that person go off and do these other things, then you’re net ahead.”

What Gates has explained is perhaps a solution to the problem that too much automation or too many robots are going to create. There is a basic law in economics which goes against the entire idea of robots destroying human jobs. It’s called the Say’s Law. One of my favourite books in economics is John Kenneth Galbraith’s A History of Economics—The Past as the Present. In A History of Economics, Galbraith writes about the Say’s Law.

This law was put forward by Jean-Baptise Say, a French businessman, who lived between 1767 and 1832. As Galbraith writes: “Say’s law held that out of the production of goods came an effective aggregate of demand sufficient to purchase the total supply of goods. Put in somewhat more modern terms, from the price of every product sold comes a return in wages, interest, profit or rent sufficient to buy that product. Somebody, somewhere, gets it all. And once it is gotten, there is spending up to the value of what is produced.”

Say’s Law essentially states that the production of goods ensures that the workers and suppliers of these goods are paid enough for them to be able to buy all the other goods that are being produced. A pithier version of this law is, “Supply creates its own demand.”

What does this mean in the context of robots destroying human jobs? If robots destroy too many human jobs, many people won’t have a regular income. If these people do not have a regular income, how are they going to buy all the products that robots are going to produce? And if they are not going to buy the products that robots are producing, how are these companies driven by robots going to survive?

Gates has offered a solution where he says that the government taxes the companies using robots, more. That money can then be used to retrain people and deploy them in areas where people are still needed.

This means that such people will be paid by the government. And when they are paid by the government they will pay income tax as well. Over and above this, these workers will also spend that money and pay several indirect taxes to the government. Hence, the government will use the money generated from taxing robots to generate more taxes for itself.

Gates suggestion is also in line with what I had said earlier about the fact that once automation becomes a real danger to human jobs, the governments will not just sit and wait it out, but will do something about it, given that there will be tremendous pressure on them from people who elected them. It will also work towards protecting its tax revenues. Hence, any government taxing the output of robots, will be in line with this.

Gates suggestion depends on several assumptions. First and foremost is that people who lose their jobs to robots will be trained for other professions. While, this sounds simple enough, it clearly isn’t. Second, it expects the governments to do the right thing. That as we all know, is easier said than done. Third, it assumes that companies will willingly pay tax on their robots and not look at loopholes to avoid making these payments.

Having said that, Gates’ suggestion still shows one way of getting through the economic mess that the robots are likely to create.

To conclude, if my job doesn’t get replaced by a robot as well, I hopefully will be around to keep writing about this trend in the months and the years to come.

Watch this space!

[i] Speech by World Bank President Jim Yong Kim: The World Bank Group’s Mission: To End Extreme Poverty, October 3, 2016

[ii] R.Bergman, Utopia for Realists—The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders and a 15-Hour Workweek, The Correspondent, 2016

[iii] Y.N.Harari, Homo Deus—A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harper, 2016

The column originally appeared in Equitymaster on February 23, 2017