Euphemisms and corporates go together.

Vishal Sikka, the bossman at Infosys, in a recent letter to the stakeholders said: “Automation itself released about 11,000 FTE [Fulltime Employee] worth of effort through the year, a clear demonstration of how software is going to play a crucial role in our business model.”

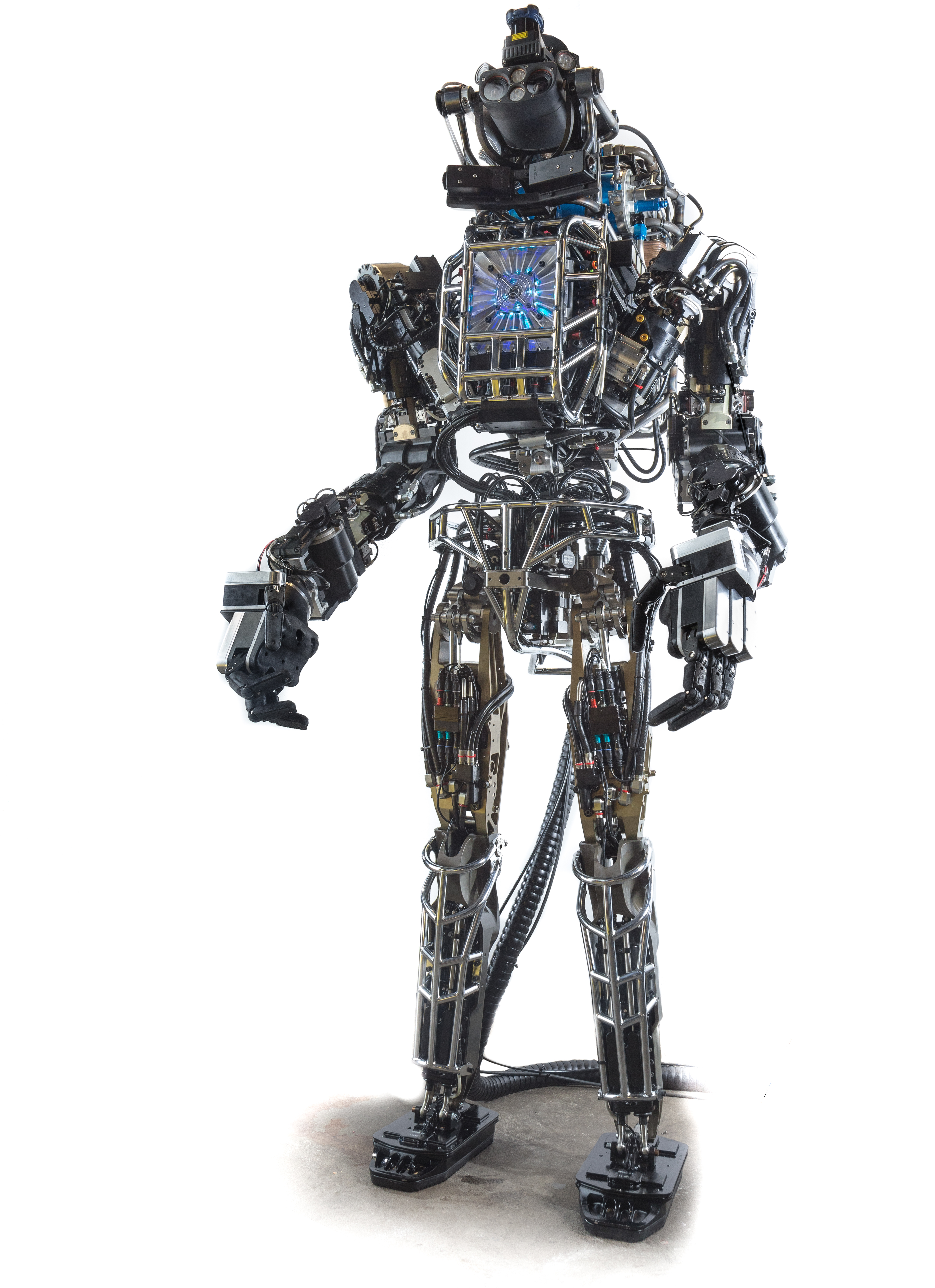

Sikka did not specify what he meant by the phrase “released about 11,000 FTE [Fulltime Employee] worth of effort through the year”. Nevertheless, the broader point is that automation or the rise of the robots, will destroy many human jobs in the years to come.

This is not the first time that the rise of the robots or automation or mechanisation has been seen as a threat to human jobs. Similar concerns were also raised at the start of the industrial revolution in the Western world, a couple of centuries back.

The industrial revolution destroyed jobs, but it created many more new jobs, which finally led to economic growth and economic progress, the world had never seen before. What has changed this time around? If at all, it has.

Human beings essentially have two kinds of abilities: a) physical ability b) cognitive abilities i.e., the ability to think, understand, reason, analyse, remember, etc. As Yuval Noah Harari writes in Homo Deus—A Brief History of Tomorrow: “As long as machines competed with us merely in physical abilities, you could always find cognitive tasks that humans do better. So machines took over purely manual jobs, while humans focussed on jobs requiring at least some cognitive skills. Yet what will happen once algorithms [another name for robots] outperform us in remembering, analysing and recognising patterns?”

The trouble is that the rise of the robots hits at the heart of the model that has created economic growth world over, for the last two centuries. Companies employed individuals, and paid them a salary. The individuals then spent this salary to meet their needs. One man’s spending was someone else’s income. This benefitted other individuals and companies and so the cycle worked.

Henry Ford, the automobile pioneer understood this and paid his workers very well. As Edward Luce writes in The Retreat of Western Liberalism: “Henry Ford… raised the wage he paid to factory employees to $5 a day, a sum that in the 1920s would afford a comfortable middle-class lifestyle.”

By the time the 1950s came around, Ford started to invest in automation and at this point of time a very interesting incident took place. The auto union leader Walter Reuther was being given a tour of a new factory which had robots. And he was asked: “How will you get union dues from them?”

To which, Reuther replied: “How will you get them to buy your cars?” The point being that only when businessmen paid their employees did they go out and spend that money. This spending benefitted the businessmen they worked for, as well as other businessmen. Many employees of Ford, went out and bought Ford cars because they were well paid.

Once companies start employing more and mor robots instead of human beings, this model of economic growth and progress will go for a complete toss. As Luce writes: “The new economy requires consumers with spending power – just as the old one did. Yet much, like the farmer who eats his seed corn, Big Data is gobbling up its source of future revenue.”

The rise of the robots or Big Data or increased automation and mechanisation, will take away human jobs. As Luce writes: “Whether you listen to utopians or dystopians, all agree the share of jobs at risk of elimination is rising. McKinsey says almost half of existing jobs are vulnerable to robots.”

If robots take over, then humans don’t earn. If they don’t earn, how will they spend money. And if they don’t have money to spend, the question is, how will the companies run by robots, make money.

This is a question that nobody seems to have an answer for.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on July 5, 2017.