The gross domestic product (GDP) figures for the period October to December 2020 were declared earlier in the day today. GDP is a measure of economic size of a country.

The good news is that the Indian economy is back on the growth path. It grew by 0.41% during the period. While the growth rate itself isn’t great, it comes on the back of six months of a covid led economic contraction. And that’s clearly good news.

But this bit most of you who follow the economy closely on the social media, must have already heard by now. So, let me give you some better news than this good news.

The Indian GDP is measured in two ways. One way is by adding up private consumption expenditure (the money you and I spend buying up things), government expenditure, investment and net exports (exports minus imports). If we leave government expenditure out of the GDP, what remains is the non-government GDP, which forms a bulk of the GDP. In the October to December period, it formed around 90.3% of the GDP.

For the GDP to grow on a sustainable basis, this part needs to grow. Given that the government is a small part of the Indian economy, it can only create so much growth by spending more and more money.

The non-government part of the GDP grew by 0.58% during October to December 2020, after contracting significantly during the first six months of the financial year.

What this tells us is that the private part of the economy recovered quite a bit during the period without the government trying to pump up economic growth. The government expenditure during the period was down by 1.13%. This is the slightly better news I was talking about.

The private consumption expenditure, which forms a major part of the non-government part of the GDP contracted by 2.37%, after having contracted much more, during the first six months of the financial year. This tells us that the consumers are gradually coming back to the market even though some apprehension still prevails. This apprehension is probably more towards going out and spending money in the services part of the economy.

The other important part of non-government GDP is investment. It grew by 2.56% during October to December, which is the best in a year’s time. For jobs to be created, this growth needs to be sustained in the months to come.

The other way of looking at size of the economy is to add up the value added by the various sectors. Of this, the services sector, from hotels to real estate to banking to trade to broadcasting to transport to public administration, form nearly half of the economy. And if economy has to get back on track, it is these sectors that need to get back on track. The services sector grew by 0.98% during the period, though this was better than the contraction seen during the first six months of the year.

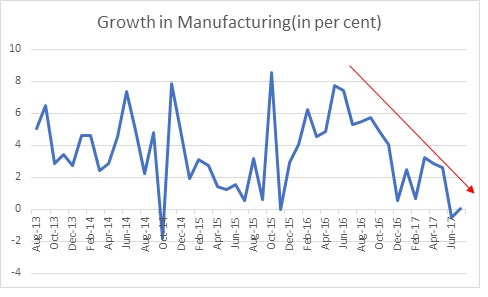

Agriculture was the standout sector and it grew by 3.92% during the period. In fact, October to December is the biggest period for agriculture during the year and the sector has done well during its biggest quarter. On the other hand, manufacturing grew by 1.65%.

What this tells us is that the economy is gradually coming back to where it was before covid. It is worth remembering here that even before covid the Indian economic growth was slowing down. All in all, the real challenge for the Indian economy will start in the second half of the 2021-22, once the base effects of the covid led economic contraction are over. As I have said in the past, the economic growth rate during the first half of 2021-22 will go through the roof, but that will be more because of base effect than anything else.

Nonetheless, even with this recovery during the second half of the financial year, the Indian economic growth is expected to contract by 8% during 2020-21. This figure has been revised upwards. The Indian GDP was earlier expected to contract by 7.7% during the year.

The main reason for this lies in the revision of the government expenditure expected during the year. As per the first advanced estimate of the GDP for 2020-21 published in early January, the government expenditure for 2020-21 was expected to be at Rs 17.48 lakh crore. In the second advanced estimate published today, it has been revised to Rs 15.87 lakh crore, a cut of 9.2%.

From the looks of it, the central government is trying to cut down on the targeted fiscal deficit of Rs 18.49 lakh crore for 2020-21. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.