Vivek Kaul

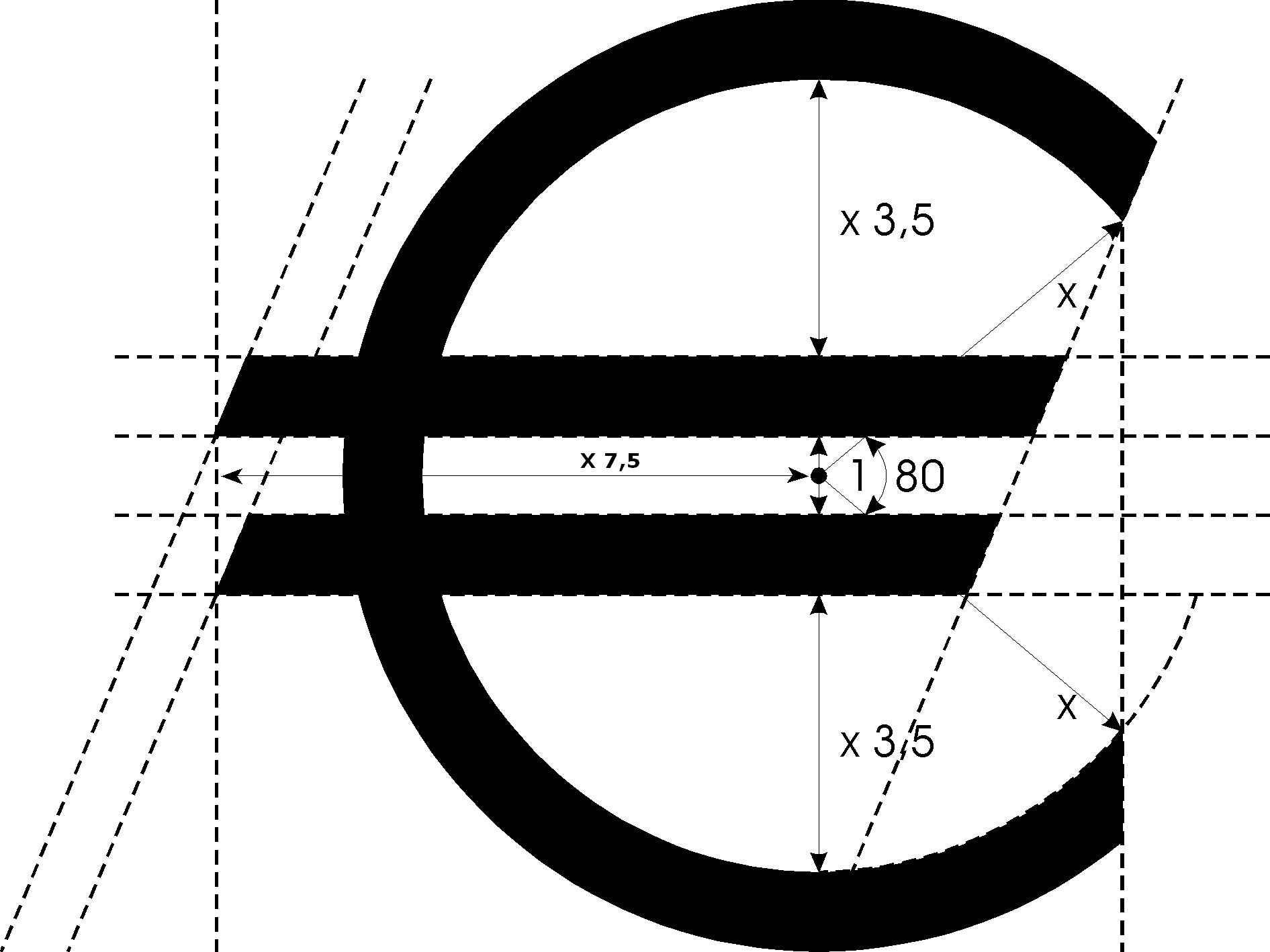

The European Central Bank (ECB) led by Mario Draghi has decided to cut its main lending rate to 0.05% from the current 0.15%. It has also decided to cut the deposit rate to –0.2%.

European banks need to maintain a certain portion of their deposits with the ECB as a reserve. This is a regulatory requirement. But banks maintain excess reserves with the ECB, over and above the regulatory requirement. This is because they do not see enough profitable lending opportunities.

As of July 2014, the banks needed to maintain reserves of € 104.43 billion with the ECB. Banks had excess reserves of € 109.85 billion over and above these reserves. The ECB was paying a negative interest rate of –0.1% on these reserves. Now it will pay them –0.2% on these reserves. This means that banks will have to pay the ECB for maintaining reserves with it, instead of being paid for it.

These rate cuts have taken the financial markets by surprise. When the ECB had last cut interest rates in June earlier this year, it had indicated that would go no further than what it had at that point of time. Nevertheless it has.

So what has prompted this ECB decision? In August 2014, inflation in the euro zone (countries which use euro as their currency) dropped to a fresh five year low 0.3%. In fact, in several countries prices have been falling. From March to July 2014, prices fell by –1.5% in Belgium, –0.4% in France, –1.6% in Italy and –1% in Spain.

In an environment of falling prices, people tend to postpone their purchases in the hope of getting a better deal in the future. This, in turn, impacts business revenues and economic growth. Falling business and economic growth leads to an increase in unemployment. And this has an impact on purchasing power of people.

Those unemployed are not in a position to purchase beyond the most basic goods and services. And those currently employed also face the fear of being unemployed and postpone their purchases. The rate of unemployment in the euro zone stood at 11.5% in July 2014. This has improved marginally from July 2013, when it was at 11.9%. The highest unemployment was recorded in Greece (27.2 % in May 2014) and Spain (24.5 %).

Hence, the ECB has cut interest rates in the hope that at lower interest rates, people will borrow and banks will lend. Once this happens, people will borrow and spend money, and that will lead to some economic growth. But is that likely the case?

The numbers clearly prove otherwise. In June 2014, the ECB decided for the first time that it would charge banks for maintaining excess reserves with it. In April 2014, the excess reserves of banks with the ECB had stood at € 91.6 billion. The hope was that banks would withdraw their excess reserves from the ECB and lend that money. The excess reserves have since increased to € 109.85 billion. What does this tell us? Banks would rather maintain excess reserves with the ECB and pay money for doing the same, rather than lend that money.

The ECB had cut the interest rate on excess deposits to 0% in July 2012. Hence, the negative interest rate on excess deposits has been around two years, without having had much impact. In fact, the loans made to companies operating in the euro zone is currently shrinking at 2.3%.

Also, banks always have the option of maintaining their excess reserves in their own vaults than depositing it with the ECB. They can always exercise that option and still not lend. Interestingly, in July 2012, the central bank of Denmark had taken interest rates into the negative territory. The lending by Danish banks fell after this move.

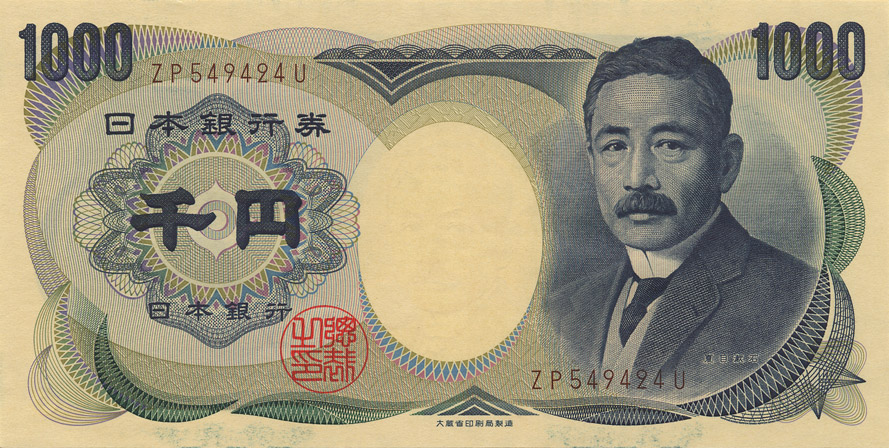

The Draghi led ECB has also decided to crank up its printing press and buy bonds, though it refused to give out the scale of the operation. The ECB plan, like has been the case with other Western central banks, is to print money and pump that money into the financial system by buying bonds. This method of operating has been named “quantitative easing” by the experts. The Federal Reserve of United States, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan have operated in this way in the past.

The hope as always is to ensure that with so much money floating around in the financial system, banks will be forced to lend and this, in turn, will rekindle economic growth.

The ECB has plans of printing money and buying covered bonds issued by banks as well as asset backed securities(ABS). Covered bonds are long-term bonds which are “secured,” or “covered,” by some specific assets of the bank like home loans or mortgages. The ABS are essentially bonds which have been created by “securitizing” loans of various kinds.

The size of the ABS market in Europe is too small, feel experts, for these purchases to have much of an impact. Nick Kounis, an economist at ABN Amro told the Economist that “the likely size of possible purchases would be €100 billion to €

150 billion.” This is too small to make any difference. Bonds covered by home loans and worth buying could amount to another € 500 billion.

Further, the buying of ABS is unlikely to begin at once. As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Telegraph put it on his blog “Buying may not begin in earnest until early next year since the ABS market is not ready.”

All this makes Evans-Pritchard conclude that “this would be a form of “QE lite” but it would be trivial compared with the huge operations of the Bank of Japan and the US Federal Reserve, together worth €120bn a month at their peak.”

If the ECB has to launch a serious form of quantitative easing it needs to be buying government bonds. But any such move is likely to be opposed by the Bundesbank, the German central bank. As the Economist put it “such an intervention would be bitterly opposed by the Bundesbank on the grounds that it would redistribute fiscal risks among the 18 member states that belong to the euro.”

The article was published on www.FirstBiz.com on Sep 5, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)