Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

A seemingly popular measure announced in today’s budget is the increase in the tax deduction allowed on home loan interest by Rs 1 lakh. Currently a deduction of Rs 1.5 lakh is allowed to someone buying his first home.

The extra deduction of Rs 1 lakh comes with caveats. The first caveat is that the house should be bought during the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014. The home loan taken should not be more than Rs 25 lakh. And the value of the house being bought should not exceed Rs 40 lakh (something that the finance minister P Chidambaram did not talk about in his budget speech). Chidambaram felt that this move will “promote home ownership and give a fillip to a number of industries like steel, cement, brick, wood, glass etc. besides jobs to thousands of construction workers.”

Let us try and understand why nothing of that sort is going to happen anywhere other than the imagination of Chidambaram. Let us say an individual who falls in the top tax bracket of 30%, takes a home loan of Rs 25 lakh at an interest of 10.5% to be repaid over a period of twenty years. The equated monthly instalment (EMI) to repay this loan would work out to around Rs 24,960. Lets assume this to be Rs 25,000 for the ease of calculation.

What is the extra saving that the individual makes? He gets a tax break of extra Rs 1 lakh. Given that he is in the 30% tax bracket, this means an yearly saving of Rs 30,000 (again lets ignore the 3% education cess for the ease of calculation). This essentially means an added saving of Rs 2,500 per month (Rs 30,000/12).

So what Chidambaram wants us to believe is that people of this country would start paying EMIs of Rs 25,000, in order to make an extra saving of Rs 2,500? No wonder he went to Harvard.

There are other problems with this deduction as well. The deduction is available only for the financial year 2013-2014 (or the assessment year 2014-2015). If the complete deduction is not used in 2013-2014, the remaining part can be used in 2014-2015(or the assessment year 2015-2016). The point is that the deduction is largely available only once. To imagine that people would buy homes to make use of what is essentially a one time deduction is stretching it rather too much. Of course the market understands this. The BSE Realty Index is down around 2.7% from yesterday’s close as I write this.

People don’t buy homes to get a tax deduction. The average middle class Indian buys a home to stay in it. And for that to happen a couple of things need to happen. The real estate prices need to fall from their current atrocious levels. And interest rates also need to fall for EMIs to become affordable.

In fact this is where another comment made by Chidambaram during the course of the speech that makes immense sense. As he said “There are 42,800 persons – let me repeat, only 42,800 persons – who admitted to a taxable income exceeding Rs 1 crore per year.”

This is nothing but a joke. There must be more people earning more than Rs 1 crore in South Delhi, let alone all of India. What this tells us very clearly is that there is a tremendous amount of black money in this country. And all these ill gotten gains are stashed away by buying real estate. This ensures that there are more investors/speculators in the real estate market, than genuine buyers.

Unless this nexus is broken down there is no way anyone who actually needs a house to live in, to be able to actually buy one.

As far as EMIs are concerned they will only come down once interest rates start falling. And for that to happen the government needs to control its borrowing. The borrowing will fall only once the fiscal deficit is under control. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

And I don’t see any of these two things happening in the near future. Neither will black money in the system come down nor will the fiscal deficit fall leading to a fall in interest rates.

Chidambaram ended his speech by quoting his favourite poet Saint Tiruvalluvar. Let me end this piece by quoting one my favourite poets, Bashir Badr.

Musaafir ke raste badalte rahe,

muqaddar mein chalna thaa chalte rahe

Mohabbat adaavat vafaa berukhi,

kiraaye ke ghar the badalate rahe

So the moral of the story is that we will continue to live in rented houses, changing them every 11 months, when the contract runs out.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek)

P Chidambaram

Subsidies = Inflation = Gold problem

The government has a certain theory on gold as per which buying gold is harmful for the Indian economy. Allow me to elaborate starting with something that P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, recently said “I…appeal to the people to moderate the demand for gold.”

India produces very little of the gold it consumes and hence imports almost all of it. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. When someone from India buys gold internationally, Indian rupees are sold and dollars are bought. These dollars are then used to buy gold.

So buying gold pushes up demand for dollars. This leads to the dollar appreciating or the rupee depreciating. A depreciating rupee makes India’s other imports, including our biggest import i.e. oil, more expensive.

This pushes up the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) as well as our fiscal deficit (the difference between what the government earns and what it spends).

The fiscal deficit goes up because as the rupee depreciates the oil marketing companies(OMCs) pay more for the oil that they buy internationally. This increase is not totally passed onto the Indian consumer. The government in turn compensates the OMCs for selling kerosene, cooking gas and diesel, at a loss. Hence, the expenditure of the government goes up and so does the fiscal deficit. A higher fiscal deficit means greater borrowing by the government, which crowds out private sector borrowing and pushes up interest rates. Higher interest rates in turn slow down the economy.

This is the government’s theory on gold and has been used to in the recent past to hike the import duty on gold to 6%. But what the theory doesn’t tells us is why do Indians buy gold in the first place? The most common answer is that Indians buy gold because we are fascinated by it. But that is really insulting our native wisdom.

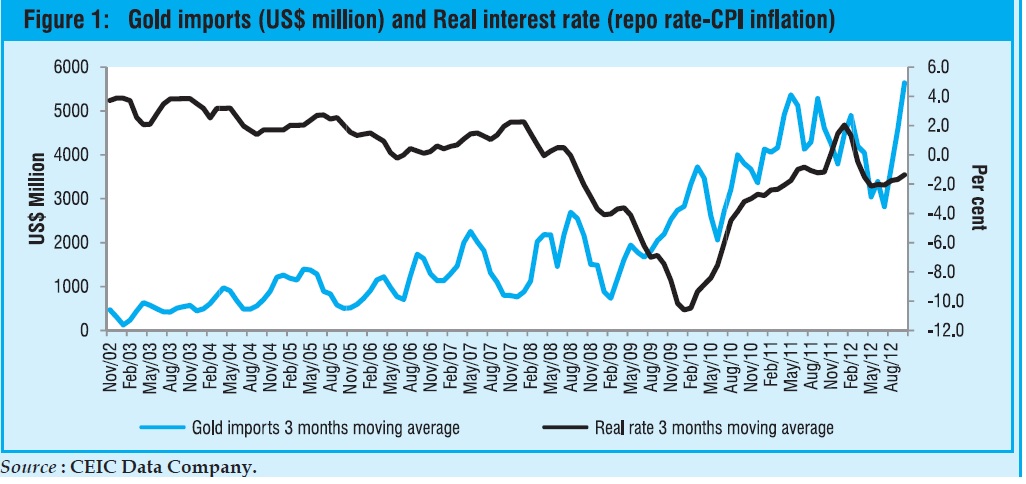

World over gold is bought as a hedge against inflation. This is something that the latest economic survey authored under aegis of Raghuram Rajan, the Chief Economic Advisor to the government, recognises. So when inflation is high, the real returns on fixed income investments like fixed deposits and banks is low. As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.”(as can be seen from the accompanying table at the start)

In simple English, people buy gold when inflation is high and the real return from fixed income investments is low. That has precisely what has happened in India over the last few years. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Survey points out.

High inflation in India has been the creation of all the subsidies that have been doled out by the UPA government. As the Economic Survey puts it “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

Inflation thus is a creation of all the subsidies being doled out, says the Economic Survey. And to stop Indians from buying gold, inflation needs to be controlled. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance,” the Survey points out. So if Indians are buying gold despite its high price and imposition of import duty, they are not be blamed.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

It is Sonia who needs to read Rajan’s Economic Survey

Vivek Kaul

Raghuram Govind Rajan, the chief economic advisor to the government of India, likes to talk straight and call a spade a spade. He was the first economist of some standing to take on Alan Greenspan’s economic policies at a public forum. In a conference in 2005, Rajan said “The bottom line is that banks are certainly not any less risky than the past despite their better capitalization, and may well be riskier. Moreover, banks now bear only the tip of the iceberg of financial sector risks…the interbank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis.”

This was during the time when the United States of America was in the middle of a real estate bubble. Everyone was having a good time. And no one wanted to spoil the party.

Alan Greenspan hadn’t achieved the ignominy that he now has, and was revered as god, at least in economic circles. Hence, any criticism of the American economy was seen as criticism of Greenspan himself. Given this, Rajan came in for heavy criticism for what he said. But we all know who turned out to be right in the end.

Recalling the occasion Rajan later wrote in his book Fault Lines “I exaggerate only a bit when I say I felt like an early Christian who had wandered into a convention of half-starved lions. As I walked away from the podium after being roundly criticised by a number of luminaries (with a few notable exceptions), I felt some unease. It was not caused by the criticism itself…Rather it was because the critics seemed to be ignoring what going on before their eyes.”

What this tells us is that Rajan doesn’t hesitate in pointing out what is going on before his eyes, even though it might be politically incorrect to do so. This clearly comes out in the Economic Survey for the year 2012-2013. A part of the summary to the first chapter State of the Economy and Prospects reads “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

The last sentence of the above paragraph makes for a very interesting reading. This is probably the first occasion where a government functionary has conceded that it is the increased government spending during the second term of the UPA that has led to a high inflationary scenario. This is not surprising given that Rajan holds a full time job teaching at the University of Chicago.

Rajan’s thinking is in line with what the late Milton Friedman, a doyen of the University of Chicago, had been talking about since the early 1960s. As Friedman writes in Money Mischief – Episodes in Monetary History: “The recognition that substantial inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon is only the beginning of an understanding of the cause and cure of inflation…Inflation occurs when the quantity of money rises appreciably more rapidly than output, and the more rapid the rise in the quantity of money per unit of output, the greater the rate of inflation. There is probably no other proposition in economics that is as well established as this one.”

And that is what has happened in India with the government spending more and more money over the last five years. This money has chased the same number of goods and services and thus led to higher prices i.e. inflation.

Rajan has never been a great fan of subsidies and he looks at them as a short term necessity. In an interview I did with him after the release of his book Fault Lines, for the Daily News and Analysis(DNA), I had asked him whether India could afford to be a welfare state, to which he had replied “Not at the level that politicians want it to.”

In another interview that I had done with him in late 2008, for the same newspaper, he had said “There is a real concern in India that government in India is not doing enough of what it should be doing…I don’t agree that we should overspend and run large deficits but I think we should bite the bullet and cut back on subsidies where we can for the larger good of the public investment into agriculture, roads etc.”

This kind of thinking that Rajan is known for clearly comes out in the Economic Survey. The subsidy bill (oil, food and fertilizer primarily) for the current financial year 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013) is estimated to be at Rs 1,90,015 crore. This has to come down. As the Economic Survey points out “Controlling the expenditure on subsidies will be crucial. Domestic prices of petroleum products, particularly diesel and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) need to be raised in line with the prices prevailing in international markets. A beginning has already been made with the decision in September 2012 to raise the price of diesel and again in January 2013 to allow oil marketing companies to increase prices in small increments at regular intervals.”

The question is that will this be enough. The amount budgeted for oil subsidies during the course of this financial year was Rs 43,580 crore. These subsidies are given to oil marketing companies because they sell diesel, cooking gas and kerosene at a loss.

The amount budgeted against oil subsidies will not be enough to meet the actual losses. As the Chapter 3 of the Economic Survey points out “The Indian basket crude oil was $107.52 per bbl (April-December) in 2012 and even with the pass through effected in the course of the year, under-recoveries of OMCs surged and were estimated at Rs1,24,854 crore during April-December 2012-13.”

So for the first nine months of the year the oil subsidy bill was more than Rs 81,000 crore off the target. By the end of the financial year this might well touch Rs 1,00,000 crore. This of course will need some clever accounting to hide. Chances are that the finance minister P Chidambaram might move this payment that will have to be made to the oil marketing companies to the next financial year.

Hence it becomes even more important to cut these subsidies in the years to come. As Rajan writes “The crucial lesson that emerges from the fiscal outcome in 2011-12 and 2012-13 is that in times of heightened uncertainties, there is need for continued risk assessment through close monitoring and for taking appropriate measures for achieving better fiscal marksmanship. Openended commitments such as uncapped subsidies are particularly problematic for fiscal credibility because they expose fiscal marksmanship to the vagaries of prices.”

The phrase to mark over here is that ‘open ended commitments such as uncapped subsidies are particularly problematic‘. This is something that Sonia Gandhi, president of the Congress party, and Chairman of UPA wouldn’t want to hear. This specially during a time when Lok Sabha elections are due in a little over a year’s time and this budget is the last occasion which the government can use to continue bribing the Indian public through subsidies.

It will be interesting to see whether the finance minister P Chidambaram takes any of the suggestions put forward by Rajan and his team, when he presents the annual budget tomorrow. Or will this Economic Survey, like many before it, be also confined to the dustbins of history?

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 27, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek )

Why Chidu can’t do a Warren Buffett in the budget

Vivek Kaul

The legendary investor Warren Buffett wrote an editorial in the New York Times sometime in August 2011 where he made an interesting point. In 2010, his income and payroll taxes came to around $6.94million. While that might sound like a lot of money, but Buffett had paid tax at a rate of only 17.4%. This was lower than any of the 20 other people who worked in Buffett’s office in Omaha, Nebraska. The tax burdens of his 20 employees mounted to anywhere between 33-41% and it averaged around 36%.

So Buffett was paying $17.4 as tax for every $100 that he earned. On the other hand his employees were paying more than double tax of $36 for every $100 that they earned. Of course that was not right.

But why was this the case? This was primarily because Buffett’s employees were paying tax on the salary they earned by working for Buffett. Buffett was making money primarily as long term capital gains on selling shares and he was paying tax on that.

The tax rate on income from salary was much higher than the tax rate on income from long capital gains made on selling shares. This benefited the rich Americans like Buffett. The richest 10% of the Americans own 80% of the stocks listed on the New York Stock Exchange as well as the NASDAQ. Buffett wants this to be set right by making the rich pay higher taxes.

In India there has been talk about making the rich pay higher taxes as well. C Rangarajan, a former RBI governor, and an economist who is known to be close to both the prime minister Manmohan Singh and finance minister P Chidambaram, had remarked in January earlier this year “We need to raise more revenues and the people with larger incomes must be willing to contribute more.”

Chidambaram himself has advocated this school of thought when he said “We should consider the argument whether the very rich should be asked to pay a little more on some occasions.”

So does taxing the rich make sense? It is not a simple yes or no answer. Allow me to explain. Like is the case in the United States, even in India different kinds of incomes are taxed at different rates.

Income from salary is taxed at the marginal rate of 10/20/30 percent whereas long term capital gains from selling shares/equity mutual funds is tax free. Short term capital gains from selling shares/equity mutual funds is taxed at 15%.

Interest earned on bank fixed deposits and savings accounts is taxed at the marginal rate of tax. So is the income earned from post office savings schemes and the senior citizens savings scheme. In comparison dividends received from shares is tax free in the hands of the investor.

Long term capital gains on debt mutual funds are taxed at 10% without indexation or 20% with indexation, whichever is lower. Indexation essentially takes inflation into account while calculating the cost of purchase. Let us say an investor buys a debt mutual fund unit at a price of Rs 100. A little over a year later he sells it at Rs 110. Let us say the inflation during the course of that year was 8%. Hence, his indexed cost of purchase will be Rs 108 (Rs 100 + 8% of Rs 100).

In this case the capital gains would be Rs 2 (Rs 110 – Rs 108) and he would end up paying a tax of 40 paisa (i.e. 20% of Rs 2). Hence, a 40 paisa tax is paid on capital gains or an income of Rs 10 (Rs 110 – Rs 100), meaning an effective income tax rate of 4% (40 paisa expressed as a percentage of Rs 10).

In case an individual had invested Rs 100 in a fixed deposit paying an interest of 10%, he would have earned Rs 10 at the end of the year as interest from it. On this he would have had to pay a minimum tax of 10%(assuming he earns enough to fall in a tax bracket) because interest earned from a fixed deposit is taxed at the marginal rate of income tax. Whereas as we saw in case of a debt mutual fund the effective rate of income tax came to around 4%.

Along similar lines long term capital gains from sale of property is taxed at 20% post indexation. So the effective rate of tax is much lower in case of capital gains made on selling property as well. In fact, even this tax need not be paid if one buys capital gains bonds or another property within a certain time frame. And given that a large portion of property transactions are in black, the effective rate of income tax comes out even lower.

The point I am trying to make is that the modes of income for the rich like share dividends, capital gains from selling shares, equity mutual funds, debt mutual funds or property for that matter, are taxed at lower effective income tax rates, in comparison to the modes of investment of the aam aadmi.

The purported logic at least in case of long term capital gains from shares being tax free is that it will encourage the so called retail investor/small investor to invest in the stock market and thus help entrepreneurs raise capital for their businesses. But that as we all know has not really happened. And essentially this regulation has been helping those who already have a lot of money. What I fail to understand further is why should investing in a debt mutual fund like a fixed maturity plan (which works precisely like a fixed deposit does and matures on a given day) be more beneficial tax wise vis a vis investing in a fixed deposit?

As we saw in the earlier example a fixed deposit investor pays minimum tax at the rate of 10% on the interest earned. He could even pay an income tax as high as 30% . On the other hand a debt mutual fund investor pays an effective tax at the rate of 4%, irrespective of which marginal rate of income tax he falls under. Why should that be the case?

I think we need to move towards a more equitable income tax structure where various modes of income, at least those earned through investing, should be taxed at the same rate. For starters indexation benefits which are currently available on debt mutual funds and sale of property should also be available when calculating the tax on interest earned on fixed deposits and savings accounts. Inflation doesn’t only impact those investing in debt mutual funds and property, it also impacts those who invest in bank fixed deposits and savings accounts.

Further long term capital gains on selling shares/equity mutual funds should be taxed at marginal rates with indexation benefits being taken into account. That would make the tax system more equitable than from what it currently is.

It would also amount to the rich paying more tax without introducing a higher tax rate or a surcharge of 10% on the highest marginal rate of 30%(which would mean an effective rate of 33%), as is being suggested currently.

Several experts are against this move and I partly agree with them. As an article in the India Today points out “Economist Surjit S. Bhalla argues that there is no real rationale for taxing the top income segment any further. Bhalla uses official data to show that the top 1.3 per cent of income taxpayers in India already account for 63 per cent of total personal tax revenue. In comparison, in the US, the top 1 per cent of taxpayers contribute just 37 per cent of total income taxes.”

That’s a fair point against higher taxes for the rich. But what we really need to know is what is the effective rate of income tax being paid by the rich? Is the situation similar to Buffett’s America, where Buffett pays an effective income tax of 17.4% whereas his employees pay an average tax of 36%? Only the Income Tax department can answer that.

Having said that, I don’t see India moving towards a more equitable income tax structure. In order to do that long term capital gains on selling stocks which is currently at zero percent would have to be done away with. And that would mean long term capital gains on stocks being taxed in a similar way as debt mutual funds/property currently are.

Hence, stock market investors would end up paying some income tax. And that as we have seen in the past, this is something they don’t like. Any attempt to tax them is met by mass selling and the stock market falling.

A falling stock market would mean that dollars being brought in by foreign investors will stop to come or slowdown. When foreign investors bring dollars, they sell those dollars to buy rupees, which they use to invest in the stock market in India. This perks up the demand for the rupee leading to its appreciation against the dollar.

A stronger rupee would mean a lower oil import bill. Oil is bought and sold internationally in dollars. If oil is worth $110 per barrel, and one dollar is worth Rs 55, it means India pays Rs 6050 per barrel ($110 x Rs 55) of oil. If one dollar is worth Rs 50, it means India pays a lower Rs 5500 per barrel ($110 x Rs 50) of oil.

Lower oil imports would help control our current account deficit which is at record levels. It would also help control our fiscal deficit as the government forces the oil marketing companies to sell products like kerosene, cooking gas and diesel at a loss and then compensates them for the loss. It would also help oil companies control their petrol losses.

This is a dynamic that Chidambaram cannot ignore. He will have to keep the foreigners and the stock market investors happy to ensure that the stock market keeps rising. Meanwhile, the rich will continued to be taxed at lower effective rates.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 21, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Why an increase in tax break won’t make people buy more homes

Vivek Kaul

It is time of the year when tax saving stories start to make it to the front page of newspapers, as the finance minister gets ready to present the annual budget of the government of India.

Today’s edition of The Hindustan Times has one such a story according to which the “the government is considering hiking the tax deduction limit on home loan interest from the present Rs 1.5 lakh to more than Rs 2 lakh per annum.”

The story goes on to quote an expert to state that this increase in tax deduction will lead to an “increase the demand for housing units and have a multiplier effect on the economy through increased demand for steel, cement and labour.”

This is what we call kite flying of the highest order. Lets try and understand why.

Currently a deduction of upto a maximum of Rs 1.5 lakh is allowed for interest paid on a home loan. At the highest tax level of 30.9% (30% tax + 3% education cess) this means a tax saving of Rs 46,350 (30.9% of Rs 1,50,000).

Now let us say this is increased to Rs 2 lakh. At the highest tax level of 30.9% this would mean a tax saving of Rs 61,800 (30.9% of Rs 2,00,000). This implies an increased tax saving of Rs 15,450 per year (Rs 61,800 minues Rs 45,350) or Rs 1287.5 per month.

So basically what The Hindustan Times story really tells us is that people of this country will buy homes because they will save Rs 1287.5 more every month. But what it does not tell us is the amount of money they will have to spend to get this extra tax saving.

Let me throw more numbers at you. The story points out “The average home loan size has grown from about Rs 17 lakh about three years ago to close to Rs 22 lakh currently.” Let us consider a 20 year home loan of Rs 22 lakh taken at an interest rate of 10% (the actual home loan interest rates might be higher currently though).

The EMI (equated monthly instalment) on this loan would be Rs 21,230.48. Hence to get an extra tax deduction of Rs 1287.5 per month any individual taking a home loan would have to first spend Rs 21,230.48 which is 16.5 times more.

I guess people of India are clearly more intelligent than that. And I don’t see many people doing that.

People don’t buy homes to get a tax deduction. The average middle class Indian buys a home to stay in it. And for that to happen a couple of things need to happen. First and foremost real estate prices need to come down because only then will EMIs become affordable.

As The Hindustan Times story points out that three years back the average home loan size was Rs 17 lakh and now it is Rs 22 lakh. This has happened because home prices have gone up since then.

A home loan of Rs 17 lakh at an interest of 10% for a period of 20 years would mean an EMI of Rs 16,405.37. Hence, EMIs have gone up by around 29.4% in the last three years. And that makes it difficult for individuals looking to buy a home to live in.

The difference between the EMIs on a home loan of Rs 22 lakh and a home loan of Rs 17 lakh is around Rs 4825. This is 3.75 times more than the extra tax saving of Rs 1287.5 that would happen when the tax deduction limit on home loan interest goes upto Rs 2 lakh per year from the current Rs 1.5 lakh.

Also to get a bigger home loan one needs a higher income as well. Hence, an income required to get a Rs 22 lakh home loan is higher than the income required to get a Rs 17 lakh home loan.

So for people to start buying homes to live in real estate prices need to fall from their current atrocious levels. Whether that happens remains to be seen. As my paternal grandfather told me late last evening “roti kapda aur makaan ka daam kabhi nahi girta. (The price of food, clothes and houses never falls).”

The second thing that needs to happen for sales of homes to pick up is a fall in interest rates. At an interest rate of 8%, a 20 year home loan of Rs 22 lakh would imply an EMI of Rs 18,401.68. This would imply a lower EMI of Rs 2828.8 than at the 10% level.

In fact I have made all the calculations at the highest rate of tax of 30%. At lower rates of tax it makes even less sense to buy a home to get an extra tax deduction. Also, the average home loan in cities is obviously higher than the Rs 22 lakh used here. In cities, it is highly unlikely one would be able to buy anything for that kind of home loan value. Hence, the argument holds even greater value for cities where prices are much higher.

To conclude, the real estate market in India has been taken over by speculators looking to put their black money to some use. And currently it is these speculators playing a game of passing the parcel among themselves. Unless that breaks people won’t start buying homes, higher tax deductions notwithstanding.

This article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 4, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])