Sometime in May last year, I wrote a column for a digital publication, in which I said that the Modi government’s luck on the oil front would run out in 2015-2016. As is wont in such cases, I was more than a little vague about exactly when would the Modi government’s luck on the oil front run out.

Sometime in May last year, I wrote a column for a digital publication, in which I said that the Modi government’s luck on the oil front would run out in 2015-2016. As is wont in such cases, I was more than a little vague about exactly when would the Modi government’s luck on the oil front run out.

I was just trying to follow an old forecasting rule: “forecast a number or forecast a date, but never both”. So, I sort of forecast a date. Honestly, I was wrong about it. The Narendra Modi government’s luck on the oil front continued through 2015.

Nevertheless, things have started to heat up in the recent past. Since February 12, 2016, the price of the Indian basket of crude oil has gone up by around 75%. As on May June 2, 2016, the price of the Indian basket for crude oil was at $46.83 per barrel.

This isn’t a column on trying to defend, what was a largely wrong forecast. What I want to explore in this column is the basic point about forecasting being a very difficult thing to do. While it’s always easy to explain things in retrospect, it is very difficult to predict how things will play out. And it is even more difficult to predict when things will play out, the way you expect them to play out.

Let’s take the basic forecast of oil prices going up. I was right about the point that when oil prices start to go up, the luck on which the good fortunes of the Modi government are built will start to run out. I will not explain it again here, given that I have explained it, often enough in the past, and perhaps might do it again, in the days to come.

Nevertheless, I got the timing wrong, despite making a very open ended forecast. There are two basic points to making a forecast—one is you expect the trend to continue—the other is you do not expect the trend to continue.

I expected that the trend of lower oil prices would not continue. While I have been right about that, but I have been wrong about the timing.

But what about forecasts, where economists and analysts, expect a trend to continue. Take the case of what economist Arvind Panagariya wrote in India—The Emerging Giant, a book that was published in 2008: “India has been growing at an average annual rate exceeding 6 percent since the late 1980s. During the four years spanning 2003-2004 and 2006-2007, its growth rate reached 8.6 percent—a level close to that experienced by the East Asian miracle economies of the Republic of Korea and Taiwan during their peak years. As the book goes to press, fears that the economy is overheating can be heard loudly, but virtually no one is predicting a significant slowdown in the growth rate in the forthcoming years.”

Panagariya, like most economists, did not see the financial crisis, coming. He also, like most economists, thought the current trend would continue. But that did not turn out to be the case. Also, most economists find it easier to say what other economists are saying. This is because if and when they are wrong, then they are wrong in a majority.

And it is safe to be wrong when everyone else is wrong. Nevertheless, if one economist forecasts something which goes against the trend and is wrong about it, then only he has to bear the consequences of being wrong. Life is easy, when everyone is wrong, and hence it makes sense to go with the herd.

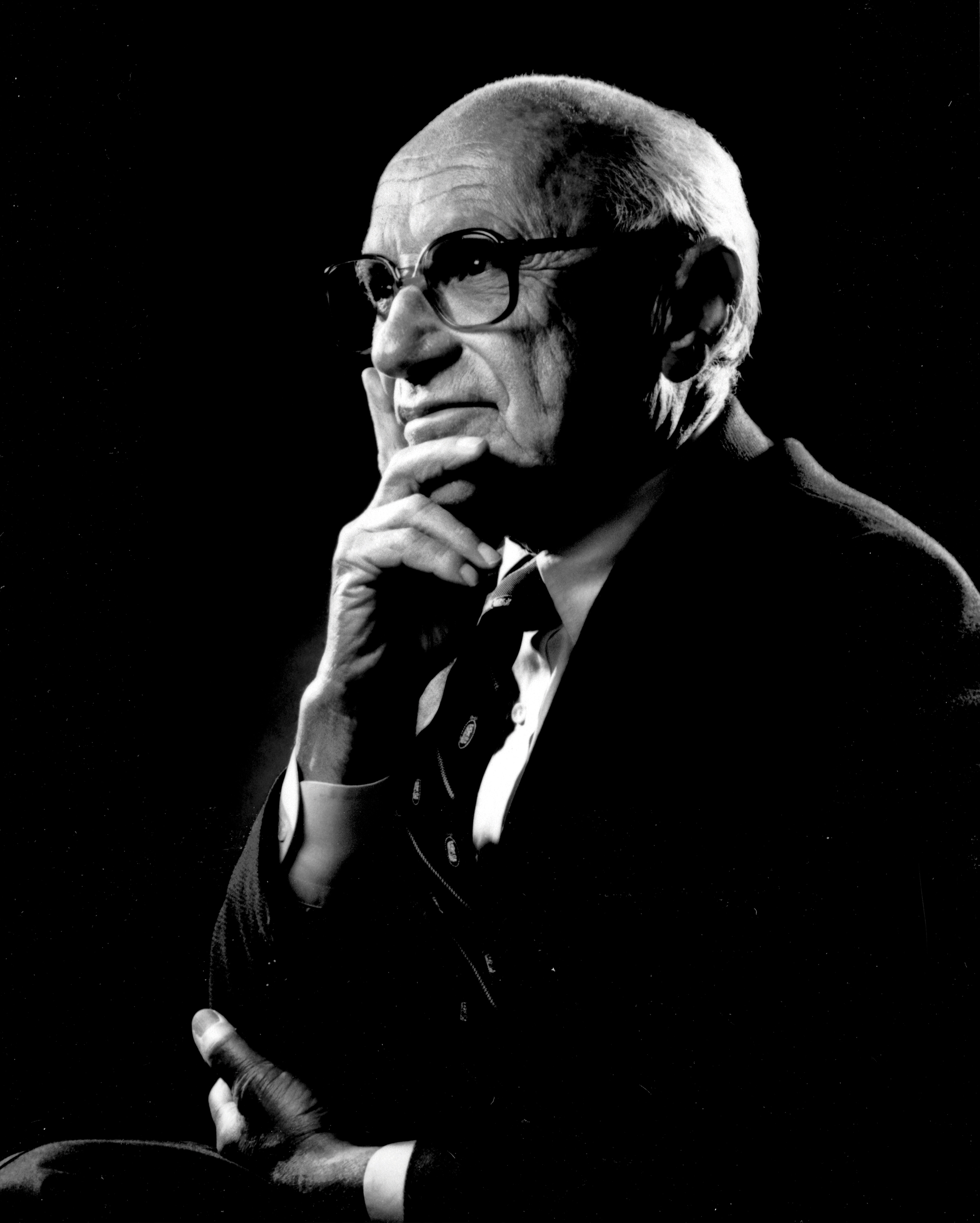

Let’s take another example here of the economist Milton Friedman and the prediction he made when the price of oil started to go up in the early 1970s.

In January 1974, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries(OPEC) raised the price of oil to $11.65 per barrel. This was after OPEC’s economic commission had determined that the price of oil should be $17 per barrel.

It was around then that the economist Milton Friedman wrote in a column in the Newsweek magazine where he predicted that “the Arabs … could not for long keep the price of crude at $10 a barrel.” For this prediction, Friedman was awarded the Booby Prize by the Association for the Promotion of Humour in International Affairs

The price of oil was quoting at more than $18 a barrel by the end of 1979. And by early 1981, it had risen four-fold and was quoting at nearly $40 a barrel. Friedman had been proven wrong for a long period of time.

In 1986, finally the price of oil was quoting again at $10 a barrel. And Friedman wrote a “I told you so” column in an issue of the Newsweek magazine which appeared on March 10, 1986. The column was titled “Right at Last, an Expert’s Dream.” This, of course, was in jest. As Friedman confessed, “Timing, as well as direction, is important…I had expected the price of oil to come down far sooner.”

Now does that mean that it makes sense to go against the herd? I wish I could say that. Over the last few years, a huge number of gold bugs have been coming out of the woodwork and predicting that gold prices will rise again. While, gold has done reasonably well in the recent past, a sustained rally in the yellow metal hasn’t been seen as yet.

So, next time you hear an analyst or an economist, make a forecast, with great confidence, it might be worth remembering that old saying in economics: “economists have predicted nine out of the last five recessions”.