Vivek Kaul

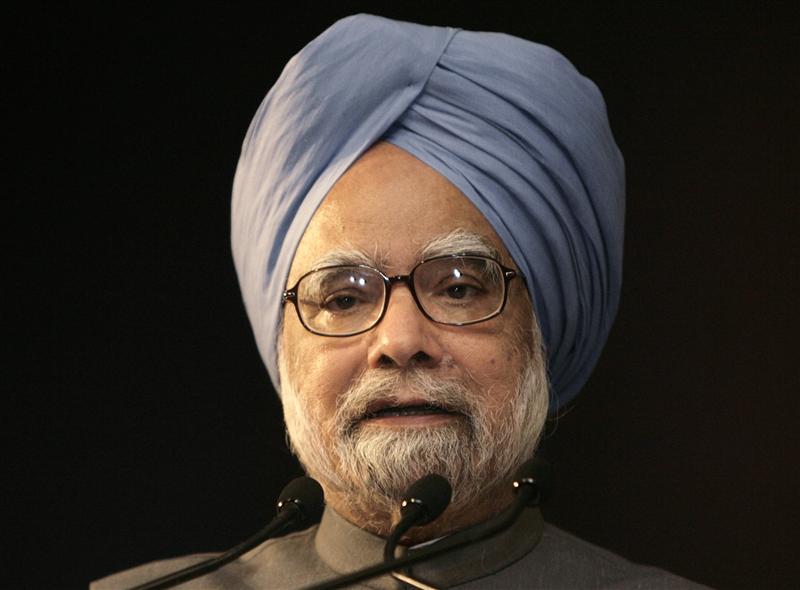

So the Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh has finally spoken. But there are multiple reasons why his defence of the free allocation of coal blocks to the private sector and public sector companies is rather weak.

“The policy of allocation of coal blocks to private parties…was not a new policy introduced by the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). The policy has existed since 1993,” the PM said in a statement to the Parliament yesterday.

But what the statement does not tell us is that of the 192 coal blocks allocated between 1993 and 2009, only 39 blocks were allocated to private and public sector companies between 1993 and 2003.

The remaining 153 blocks or around 80% of the blocks were allocated between 2004 and 2009. Manmohan Singh has been PM since May 22, 2004. What makes things even more interesting is the fact that 128 coal blocks were given away between 2006 and 2009. Manmohan Singh was the coal minister for most of this period.

Hence, the defence of Manmohan Singh that they were following only past policy falls flat. Given this, giving away coal blocks for free is clearly UPA policy. Also, we need to remember that even in 1993, when the policy was first initiated a Congress party led government was in power.

The PM further says that “According to the assumptions and computations made by the CAG, there is a financial gain of about Rs. 1.86 lakh crore to private parties. The observations of the CAG are clearly disputable.”

What is interesting is that in its draft report which was leaked earlier in March this year, the Comptroler and Auditor General(CAG) of India had put the losses due to the free giveaway of coal blocks at Rs 10,67,000 crore, which was equal to around 81% of the expenditure of the government of India in 2011-2012.

Since then the number has been revised to a much lower Rs 1,86,000 crore. The CAG has arrived at this number using certain assumptions.

The CAG did not consider the coal blocks given to public sector companies while calculating losses. The transaction of handing over a coal block was between two arms of the government. The ministry of coal and a government owned public sector company (like NTPC). In the past when such transactions have happened revenue from such transactions have been recognized.

A very good example is when the government forces the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India to forcefully buy shares of public sector companies to meet its disinvestment target. One arm of the government (LIC) is buying shares of another arm of the government (for eg: ONGC). And the money received by the government is recognized as revenue in the annual financial statement.

So when revenues from such transactions are recognized so should losses. Hence, the entire idea of the CAG not taking losses on account of coal blocks given to pubic sector companies does not make sense. If they had recognized these losses as well, losses would have been greater than Rs 1.86lakh crore. So this is one assumption that works in favour of the government. The losses on account of underground mines were also not taken into account.

The coal that is available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But the entire coal cannot be mined due to various reasons including those of safety. The part that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve. The extractable reserves of these blocks (after ignoring the public sector companies and the underground mines) came to around 6282.5 million tonnes. The average benefit per tonne was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated August 21, 2012,”The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs1028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL(Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the Ministry of Coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012 a further allowance of Rs150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly the average benefit of Rs295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6282.5 million tonne calculated as above.”

Using this is a very conservative method CAG arrived at the loss figure of Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes).

Manmohan Singh in his statement has contested this. In his statement the PM said “Firstly, computation of extractable reserves based on averages would not be correct. Secondly, the cost of production of coal varies significantly from mine to mine even for CIL due to varying geo-mining conditions, method of extraction, surface features, number of settlements, availability of infrastructure etc.”

As the conditions vary the profit per tonne of coal varies. To take this into account the CAG has calculated the average benefit per tonne and that takes into account the different conditions that the PM is referring to. So his two statements in a way contradict each other. Averages will have been to be taken into consideration to account for varying conditions. And that’s what the CAG has done.

The PM’s statement further says “Thirdly, CIL has been generally mining coal in areas with

better infrastructure and more favourable mining conditions, whereas the coal blocks offered for captive mining are generally located in areas with more difficult geological conditions.”

Let’s try and understand why this statement also does not make much sense. As The Economic Times recently reported, in November 2008, the Madhya Pradesh State Mining Corporation (MPSMC) auctioned six mines. In this auction the winning bids ranged from a royalty of Rs 700-2100 per tonne.

In comparison the CAG has estimated a profit of only Rs 295.41 per tonne from the coal blocks it has considered to calculate the loss figure. Also the mines auctioned in Madhya Pradesh were underground mines and the extraction cost in these mines is greater than open cast mines. The profit of Rs 295.41was arrived at by the CAG by considering only open cast mines were costs of extraction are lower than that of underground mines.

The fourth point that the PM’s statement makes is that “Fourthly, a part of the gains would in any case get appropriated by the government through taxation and under the MMDR Bill, presently being considered by the parliament, 26% of the profits earned on coal mining operations would have to be made available for local area development.”

Fair point. But this will happen only as and when the bill is passed. And CAG needs to work with the laws and regulations currently in place.

A major reason put forward by Manmohan Singh for not putting in place an auction process is that “major coal and lignite bearing states like West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and Rajasthan that were ruled by opposition parties, were strongly opposed to a switch over to the process of competitive bidding as they felt that it would increase the cost of coal, adversely impact value addition and development of industries in their areas.”

That still doesn’t explain why the coal blocks should have been given away for free. The only thing that it does explain is that maybe the opposition parties also played a small part in the coal-gate scam.

To conclude Manmohan Singh might have been better off staying quiet. His statement has raised more questions than provided answers. As he said yesterday “Hazaaron jawabon se acchi hai meri khamoshi, na jaane kitne sawaalon ka aabru rakhe”.For once he should have practiced what he preached.

(The article originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 29,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/column_why-manmohan-singh-was-better-off-being-silent_1734007))

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Manmohan Singh

Of 9% economic growth and Manmohan’s pipedreams

Vivek Kaul

Shashi Tharoor before he decided to become a politician was an excellent writer of fiction. It is rather sad that he hasn’t written any fiction since he became a politician. A few lines that he wrote in his book Riot: A Love Story I particularly like. “There is not a thing as the wrong place, or the wrong time. We are where we are at the only time we have. Perhaps it’s where we’re meant to be,” wrote Tharoor.

India’s slowing economic growth is a good case in point of Tharoor’s logic. It is where it is, despite what the politicians who run this country have to say, because that’s where it is meant to be.

The Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in his independence-day speech laid the blame for the slowing economic growth in India on account of problems with the global economy as well as bad monsoons within the country. As he said “You are aware that these days the global economy is passing through a difficult phase. The pace of economic growth has come down in all countries of the world. Our country has also been affected by these adverse external conditions. Also, there have been domestic developments which are hindering our economic growth. Last year our GDP grew by 6.5 percent. This year we hope to do a little better…While doing this, we must also control inflation. This would pose some difficulty because of a bad monsoon this year.”

So basically what Manmohan Singh was saying that I know the economic growth is slowing down, but don’t blame me or my government for it. Singh like most politicians when trying to explain their bad performance has resorted to what psychologists calls the fundamental attribution bias.

As Vivek Dehejia an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, told me in a recent interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) “Fundamentally attribution bias says that we are more likely to attribute to the other person a subjective basis for their behaviour and tend to neglect the situational factors. Looking at our own actions we look more at the situational factors and less at the idiosyncratic individual subjective factors.”

In simple English what this means is that when we are analyzing the performance of others we tend to look at the mistakes that they made rather than the situational factors. On the flip side when we are trying to explain our bad performance we tend to blame the situational factors more than the mistakes that we might have made.

So in Singh’s case he has blamed the global economy and the deficient monsoon for the slowing economic growth. He also blamed his coalition partners. “As far as creating an environment within the country for rapid economic growth is concerned, I believe that we are not being able to achieve this because of a lack of political consensus on many issues,” Singh said.

Each of these reasons highlighted by Singh is a genuine reason but these are not the only reasons because of which economic growth of India is slowing down. A major reason for the slowing down of economic growth is the high interest rates and high inflation that prevails. With interest rates being high it doesn’t make sense for businesses to borrow and expand. It also doesn’t make sense for you and me to take loans and buy homes, cars, motorcycles and other consumer durables.

The question that arises here is that why are banks charging high interest rates on their loans? The primary reason is that they are paying high interest rate on their deposits.

And why are they paying a high interest rate on their deposits? The answer lies in the fact that banks have been giving out more loans than raising deposits. Between December 30, 2011 and July 27, 2012, a period of nearly seven months, banks have given loans worth Rs 4,16,050 crore. During the same period the banks were able to raise deposits worth Rs 3,24,080 crore. This means an incremental credit deposit ratio of a whopping 128.4% i.e. for every Rs 100 raised as deposits, the banks have given out loans of Rs 128.4.

Thus banks have not been able to raise as much deposits as they are giving out loans. The loans are thus being financed out of deposits raised in the past. What this also means is that there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits and hence banks have had to offer higher interest rates than normal to raise this money.

So the question that crops up next is that why there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits? This as I have said more than few times in the past is because the expenditure of the government is much more than its earnings.

The fiscal deficit of the government or the difference between what it earns and what it spends has been going up, over the last few years. For the financial year 2007-2008 the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. It went up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for financial year 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore.

This difference is made up for by borrowing. When the borrowing needs of the government go through the roof it obviously leaves very little on the table for the banks and other private institutions to borrow, which in turn means that they have to offer higher interest rates to raise deposits. Once they offer higher interest rates on deposits, they have to charge higher interest rate on loans.

A higher interest rate scenario slows down economic growth as companies borrow less to expand their businesses and individuals also cut down on their loan financed purchases. This impacts businesses and thus slows down economic growth.

The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum. One of the programmes that benefits from the government subsidy is Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The scheme guarantees 100 days of work to adults in any rural household. While this is a great short term fix it really is not a long term solution. If creating economic growth was as simple as giving away money to people and asking them to dig holes, every country in the world would have practiced it by now.

As Raghuram Rajan, who is taking over as the next Chief Economic Advisor of the government of India, told me in an interview I did for DNA a couple of years back “The National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS, another name for MGNREGA), if appropriately done it is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key.”

But the Manmohan Singh led United Progressive Alliance seems to be looking at the employment guarantee scheme as a long term solution rather than a short term fix. This has led to burgeoning wage inflation over the last few years in rural areas.

As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “The wages guaranteed by MGNREGA pushed rural wage inflation up to 15 percent in 2011”.

Also as more money in the hands of rural India chases the same number of goods it has led to increased price inflation as well. Consumer price inflation currently remains over 10%. The most recent wholesale price index inflation number fell to 6.87% for the month of July 2012, from 7.25% in June. But this experts believe is a short term phenomenon and inflation is expected to go up again in the months to come.

As Ruchir Sharma wrote in a column that appeared yesterday in The Times of India “For decades India’s place in the rankings of nations by inflation rates also held steady, somewhere between 78 and 98 out of 180. But over the past couple of years India’s inflation rate is so out of whack that its ranking has fallen to 151. No nation has ever managed to sustain rapid growth for several decades in the face of high inflation. It is no coincidence that India is increasingly an outlier on the fiscal front as well with the combined central and state government deficits now running four times higher than the emerging market average of 2%.” (You can read the complete column here).

So to get economic growth back on track India has to control inflation. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been trying to control inflation by keeping the repo rate, or the rate at which it lends to banks, at a high level. One school of thought is that once the RBI starts cutting the repo rate, interest rates will fall and economic growth will bounce back.

That is specious argument at best. Interest rates are not high because RBI has been keeping the repo rate high. The repo rate at best acts as an indicator. Even if the RBI were to cut the repo rate the question is will it translate into interest rate on loans being cut by banks? I don’t see that happening unless the government clamps down on its borrowing. And that will only happen if it’s able to control the subsidies.

The fiscal deficit for the current financial year 2012-2013 has been estimated at Rs Rs Rs 5,13,590 crore. I wouldn’t be surprised if the number even touches Rs 600,000 crore. The oil subsidy for the year was set at Rs 43,580 crore. This has already been exhausted. Oil prices are on their way up and brent crude as I write this is around $115 per barrel. The government continues to force the oil marketing companies to sell diesel, LPG and kerosene at a loss. The diesel subsidy is likely to continue given that with the bad monsoon farmers are now likely to use diesel generators to pump water to irrigate their fields. With food inflation remaining high the food subsidy is also likely to go up.

The heart of India’s problem is the huge fiscal deficit of the government and its inability to control it. As Sharma points out in Breakout Nations “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period…If the government continues down this path India, may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

These details Manmohan Singh couldn’t have mentioned in his speech. But he tried to project a positive picture by talking about the planning commission laying down measures to ensure a 9% rate of growth. The one measure that the government needs to start with is to cut down the fiscal deficit. And the probability of that happening is as much as my writing having more readers than that of Chetan Bhagat. Hence India’s economic growth is at a level where it is meant to be irrespective for all the explanations that Manmohan Singh gave us and the hope he tried to project in his independence-day speech.

But then you can’t stop people from dreaming in broad daylight. Even Manmohan Singh! As the great Mirza Ghalib who had a couplet for almost every situation in life once said “hui muddat ke ghalib mar gaya par yaad aata hai wo har ek baat par kehna ke yun hota to kya hota?”

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 16,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/of-9-economic-growth-and-manmohans-pipedreams-419371.html)

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

Raghuram Rajan’s advice isn’t what UPA may want to hear

Vivek Kaul

Every year the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, one of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks in the United States, organizes a symposium at Jackson Hole in the state of Wyoming. The conference of 2005 was to be the last conference attended by Alan Greenspan, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank.

Hence, the theme for the conference was the legacy of the Greenspan era. One of the economists who had been invited to present a paper at the symposium was the 40 year old Raghuram Govind Rajan, the man who is likely to be the government’s next Chief Economic Advisor.

Rajan is an alumnus of IIT Delhi, IIM Ahmedabad and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After doing his PhD at MIT, he had joined the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago (now known as the Booth School of Business). At that point of time Rajan was on leave from the business school and was working as the Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund.

The United States had seen an era of unmatched economic prosperity under Greenspan. Even, the dotcom bust in 2000-2001 hadn’t held America back. Greenspan had managed to get the economy back on track by cutting the Federal Funds Rate to as low as 1% by mid 2003. The low interest rate scenario along with a lot of financial innovation had created a financial system which was slush with money. American banks were falling over one another to lend money. And borrowers were borrowing as much as they could to buy homes, property and real estate. The dotcom bubble of the late 1990s had given away to the real estate bubble.

In a survey of home buyers carried out in Los Angeles in 2005, the prevailing belief was that prices will keep growing at the rate of 22% every year over the next 10 years. This meant that a house which cost a million dollars in 2005 would cost around $7.3million by 2015. Such was the belief in the bubble.

And the belief was not limited to only the people of United States. Banks were equally optimistic that real estate prices will continue to go up. Between 2004 and 2006, banks and other financial institutions playing in the subprime home loan space gave out loans worth $1.7trillion in total. Of this a massive $625billion was lent in 2005, the year Rajan was invited to speak at Jackson Hole.

In its strictest sense a subprime loan was defined as a loan given to an individual with a credit score below 620, who had no assets and was thus unlikely to qualify for a traditional home loan. A credit score is a number calculated on the basis of the borrower’s past record at paying bills and loans of all kinds, the length of his credit history, the kind of loans taken etc. On the basis of the number the lender can get some sort of an idea of what sort of a risk he is taking on by lending to the borrower.

That was the purported idea behind the credit score. In the normal scheme of things, a borrower categorized as “sub-prime” should not have been touched with a bargepole. But those were days when everybody and anybody got a loan.

It was an era of optimism which had been fueled by easy money that was going around in the financial system. The conventional wisdom of the day was that the bull run in property prices would continue forever. The American economy would continue to prosper.

In this environment Raghuram Rajan presented a paper titled “Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?” In his speech Rajan harped on the fact that the era of easy money would get over soon and would not last forever as the conventional wisdom expected it to.

He said:

The bottom line is that banks are certainly not any less risky than the past despite their better capitalization, and may well be riskier. Moreover, banks now bear only the tip of the iceberg of financial sector risks…the interbank market could freeze up, and one could well have a full-blown financial crisis

He also suggested in his speech that the incentives of the financial sector were skewed and employees were reaping in rich rewards for making money but were only penalized lightly for losses. In the last paragraph of his speech Rajan said it is at such times that “excesses typically build up. One source of concern is housing prices that are at elevated levels around the globe.”

Rajan’s speech did not go down well with people at the conference. This is not what they wanted to hear. Also in a way Rajan was questioning the credentials of Alan Greenspan who would soon retire spending nearly 18 years as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States. He was essentially saying that the Greenspan era was hardly what it was being made out to be.

Given this, Rajan came in for heavy criticism. As he recounts in his book Fault Lines – How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy:

Forecasting at that time did not require tremendous prescience: all I did was connect the dots… I did not, however, foresee the reaction from the normally polite conference audience. I exaggerate only a bit when I say I felt like an early Christian who had wandered into a convention of half-starved lions. As I walked away from the podium after being roundly criticized by a number of luminaries (with a few notable exceptions), I felt some unease. It was not caused by the criticism itself…Rather it was because the critics seemed to be ignoring what going on before their eyes.

The criticism notwithstanding Rajan turned out right in the end. And what was interesting that he called it as he saw it. He called spade a spade despite the aura of Alan Greenspan that prevailed.

What this story clearly tells us is that Rajan is not an “on-the-other-hand” economist. There are too many “on-the-other-hand” economists going around, who do not like to take a stand on an issue. As Harry Truman, an American President once famously said “All my economists say, ‘on the one hand… and on the other hand…Someone give me a one-handed economist!”

If news-reports in the media are to be believed the government is in the process of appointing Rajan as the Chief Economic Advisor to replace Kaushik Basu. As far as academic credentials and experience go they don’t come much better than Rajan. Other than having been the Chief Economist of the IMF between September 2003 and January 2007, he is also currently an honorary economic adviser to the Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

The question though is will the plain-speaking Rajan who seems to like to call a spade a space, fit into a government which believes in the idea of a welfare state? In an interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) after the release of his book Fault Lines I had asked him “whether India can afford a welfare state?” “Not at the level that politicians want it to. For example, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), if appropriately done it is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key,” Rajan had replied.

This is a view that is not held by many in the present United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. They politicians who run this country have great faith in the NREGS.

Rajan had also written in Fault Lines that “the license permit raj has given away to the raj of the land mafia.” I had asked him to explain this in detail and he had said:

“Earlier…you had to navigate the government for permissions and this was license permit. You needed permission to produce. Now you have to navigate the government for land because in many situations land titles are murky, acquiring the land is difficult, and even after you acquire protecting that land is difficult. So there are entrepreneurs who have access to the power of the government, who basically can do it. And then there are others who can’t. So you have made it a test of who can acquire the land in certain kind of functions than who is the best developer than who is the best manufacturer. Put differently what used to surround the license permit has moved to corruption surrounding land. The central source of wealth today in the whole economy is land and we need to make the land acquisition process transparent.”

In answer to another question Rajan had said:

“The predominant of the sources of mega wealth in India today are not the software billionaires who have made money the hard way by being competitive in a global economy. It is the guys who have access to natural resources or to land or to particular infrastructure permits or licenses. In other words proximity to the government seems to be a big source of wealth. And that is worrisome because it means that those who can access the government who can manage it are in a sense far more powerful than ordinary businessmen. In the long run this leads to decay in the image of businessmen and the whole free enterprise system. It doesn’t show us in good light if we become a country of oligopolies and oligarchs and eventually this could even impinge on democratic right.”

What these answers tell us is that Rajan has clear views on issues that plague India and he is not afraid of putting them forward. But these are things that the current government would not like to hear. Given this, it remains to be seen how effective Rajan’s tenure in the government will turn out to be. The trouble is if he calls a spade a spade, it won’t take much time for the government to marginalize him. If he does not, he won’t be effective anyway.

(The interview originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 8,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/raghuram-rajans-advice-isnt-what-upa-may-want-to-hear-410694.html/)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected] )

Reform by stealth, the original sin of 1991, has come back to haunt us

India badly needs a second generation of economic reforms in the days and months to come. But that doesn’t seem to be happening. “What makes reforms more difficult now is what I call the original sin of 1991. What happened from 1991 and thereon was reform by stealth. There was never an attempt made to sort of articulate to the Indian voter why are we doing this? What is the sort of the intellectual or the real rationale for this? Why is it that we must open up?” says Vivek Dehejia an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa,Canada. He is also a regular economic commentator on India for the New York Times India Ink. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

How do you see overall Indian economy right now?

The way I would put it Vivek is, if I take a long term view, a generational view, I am pretty optimistic. The fundamentals of savings and investments are strong.

What about a more short term view?

If you take a shorter view of between six months to a year or even two years ahead, then everything that we have been reading about in the news is worrisome. The foreign direct investment is drying up. The savings rate seems to have been dropping. The economic growth we know has dropped. The next fiscal year we would lucky if we get 6.5% economic growth.

How do we account for the failure of this particular government to deliver sort of crucially needed second generation economic reforms?

The India story is a glass half empty or a glass half full. If you look at the media’s treatment of the India story, particularly international media they tend to overshoot. So two years ago we were being overhyped. I remember that the Economist had a famous cover where they said that India will overtake China’s growth rate in the next couple of years. They made that bold prediction. And then about a year later they were saying that India is a disaster. What has happened to the India story? The international media tends to overshoot. And then they overdo it in the negative direction as well. A balanced view would say that original hype was excessive. We cannot do nor would we want to do what China is doing. With our democratic system, our pluralistic democracy, the India that we have, we cannot marshal resources like the way the Chinese do, or like the way Singapore did.

Could you discuss that in detail?

If you take a step back, historically, many of the East Asian growth miracles, the Latin American growth miracles, were done under brutal dictatorial regimes. I mean whether it was Pinochet’s Chile, whether it was Taiwan or Singapore or Hong Kong, they all did it under authoritarian regimes. So the India story is unique. We are the only large emerging economy to have emerged as a fully fledged democracy the moment we were born as a post colonial state and that is an incredibly daring thing to do. At the time when the Constituent Assembly was figuring out what are we going to do now post independence a lot of conservative voices were saying don’t go in for full fledged democracy where every person man or a woman gets a vote because you will descend down into pluralism and identity based politics and so on. Of course to some extent it’s true. A country with a large number of poor people which is a fully fledged democracy, the centre of gravity politically is going to be towards redistribution and not towards growth. So any government has to reckon with the fact that where are your votes. In other words the market for votes and the market for economic reform do not always correlate.

You talk about authoritarian regimes and growth going together…

This is one of the oldest debates in social sciences. It is a very unsettled and a very controversial one. For any theory you can give on one side of it there is an equally compelling argument on the other side. So the orthodox view in political science particularly more than economics was put forward by Samuel Huntington. The view was that you need to have some sort of political control, you cannot have a free for all, and get marshalling of resources and savings rate and investment rate, that high growth demands.

So Huntington was supportive of the Chinese model of growth?

Yes. Huntington famously was supportive of the Chinese model and suggested that was what you had to do at an early stage of economic development. But there are equally compelling arguments on the other side as well. The idea is that democracy gives a safety valve for a discontent or unhappiness or for popular expression to disapproval of whatever the government or the regime in power is doing. We read about the growing number of mysterious incidents in China where you can infer that people are rioting. But we are not exactly sure because the Chinese system also does not allow for a free media. Also let’s not forget that China has had growing inequalities of income and growth, and massive corruption scandals. The point being that China too for its much wanted economic efficiency also has kinds of problems which are not much different from the once we face.

That’s an interesting point you make…

Here again another theory or another idea which can help us interpret what is going on. When you have a period of rapid economic growth and structural transformation of an economy, you are almost invariably going to have massive corruption. It is almost impossible to imagine that you have this huge amount of growth taking place in a relatively weak regulatory environment where there isn’t going to be an opportunity for corruption. It doesn’t mean that it is okay or it doesn’t mean that one condones it, but if you look throughout history it’s always been the case that in the first phase of rapid growth and rapid transformation there has been corruption, rising inequalities and so on.

Can you give us an example?

The famous example is the so called American gilded age. In the United States after the end of the Civil War (in the 1860s) came the era of the Robber Barons. These people who are now household names the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, the Mellons, were basically Robber Barons. They were called that of course because how they operated was pretty shady even according to the rules of that time.

Why are the second generation of reforms not happening?

What makes reforms more difficult now is what I call the original sin of 1991. We had a first phase of the economic reforms in 1991 where we swept away the worst excesses of the license permit raj. We opened up the product markets. But what happened from 1991 and thereon was reform by stealth. Reform by the stroke of the pen reform and reform in a mode of crisis, where there was never an attempt made to sort of articulate to the Indian voter why are we doing this? What is the sort of the intellectual or the real rationale for this? Why is it that we must open up? It wasn’t good enough to say that look we are in a crisis. Our gold reserves have been mortgaged. Our foreign exchange reserves are dwindling. Again India’s is hardly unique on this. Wherever you look whether it is Latin America or Eastern Europe, it generally takes an economic crisis to usher in a period of major economic reform.

So the original sin is still haunting us?

The original sin has come back to haunt us because the intellectual basis of further reform is not even on anyone’s agenda. Discussions and debates on reform are more focused on issues like the FDI is falling, the rupee is falling, the current account deficit is going up etc. Those are all symptoms of a problem. The two bursts of reform that we had first were first under Rao/Manmohan Singh and then under NDA. If a case had been made to build a constituency for economic reform, then I think we would have been in a different political economy than we are now. But the fact that didn’t happen and things were going well, the economy was growing, that led to a situation where everybody said let’s carry on. But now we don’t have that luxury. Now whichever government whoever comes to power in 2014 is going to have to make some tough decisions that their electoral base, isn’t going to like necessarily. So how are they going to make their case?

So are you suggesting that the next generation of reforms in India will happen only if there is an economic crisis?

I don’t want to say that. Again that could be one interpretation from the arguments I am making of the history. It will require a change in the political equilibrium and certainly a crisis is one thing that can do that. But a more benign way the same thing can happen that without a crisis is the realization of the political actors that look I can make economic reform and economic growth electorally a winning policy for me. But India is a land of so many paradoxes. A norm of the democratic political theory in the rich countries i.e. the US, Canada, Great Britain etc, is that other things being equal, the richer you are, the more educated you are, the more likely you are to vote. In India it is the opposite. The urban middle class is the more disengaged politically. They feel cynical. They feel powerless. Until they become more politically engaged that change in the equilibrium cannot happen.

What about the rural voter?

The rural voter at least in the short run might benefit from a NREGA and will say that you are giving me money and I will keep voting for you. We have all heard people say they are uneducated and they are ignorant, no it’s not like that. He is in a very liquidity constrained situation. He is looking to the next crop, the next harvest, the next I got to pay my bills. If someone gave him 100 days of employment and gives him a subsidy, he will take it.

How do explain the dichotomy between Manmohan Singh’s so called reformist credentials and his failure to carry out economic reforms?

One of the misconceptions that crops up when we look at poor economic performance or failure to carry out economic reform is what cognitive psychologists call fundamental attribution bias. Fundamentally attribution bias says that we are more likely to attribute to the other person a subjective basis for their behaviour and tend to neglect the situational factors. Looking at our own actions we look more at the situational factors and less at the idiosyncratic individual subjective factors. So what am I trying to say? What I am saying is that it has become almost a refrain to say that Dr Manmohan Singh should be an economic reformer. He was at least the instrument if not the architect of the 1991 reforms. There are speculations being in made in what you can call the Delhi and Mumbai cocktail party circuit, about whether he is really a reformer? Was it Narsimha Rao who was really the real architect of the reform? Is he a frustrated reformer? What does he really want to do? What’s going on his head? That in my view is a fundamental attribution bias because we are attributing to him or whoever is around him a subjective basis for the inaction and the policy paralysis of the government.

So the government more than the individual at the helm of it is to be blamed?

Traditionally the electoral base of the Congress party has been the rural voter, the minority voters and so on, people who are at the lower end of the economic spectrum. So they are the beneficiaries just roughly speaking of the redistributive policies. Political scientists have a fancy name for it. They call it the median voter theorem. What does it mean? It means that all political parties will tend to gravitate towards the preferred policy of the guy in the middle, the median voter.

Was Narsimha Rao who was really the real architect of the reform?

Narsimha Rao must be given a lot of credit for taking what was then a very bold decision. He was at the top of a very weak government as you know. And he gave the political backing to Manmohan Singh to push this first wave of reforms more than that would have been necessary just to avert a foreign exchange crisis. And then he paid a price for it electorally in the next election. This again the intangible element in the political economy that short of a crisis it often takes someone of stature to really take that long term generation view. IT means that you are not just looking at narrow electoral calculus but you are looking beyond the next election. That’s what seems to be missing right now. Among all the political parties right now, one doesn’t seem to see that vision of look at this is where we want to be in a generation and here is our roadmap of how we are going to get there.

Going back to Manmohan Singh you called him an overachiever recently, after the Time magazine called him an “underachiever”. What was the logic there?

The traditional view and certainly that was widely in the West at least till very recently has been that it was Manmohan Singh who was the architect of the India’s economic reforms. But then how do you explain the inaction in the last five, six, seven years? The revisionist perspective would say no in fact the real reformer was Narsimha Rao to begin with. The real political weight behind the reform was his. And Manmohan Singh that any good technocratic economist should have been able to do which is to implement a series of reforms that we all knew about. My teacher Jagdish Bhagwati had been writing about it for years. In that sense maybe Manmohan Singh was given too much credit in the first instance for implementing a set of reforms. If you look at his career since then he has never really been a politically savvy actor. We have this peculiar situation in India since 2004 where the Prime Minister sits in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house. That kind of thing is not barred by our constitution but I don’t think that the framers of the constitution envisaged this would be a long term situation. It is a little like the British prime minister sitting in the House of Lords. I mean that practice disappeared in the nineteenth century. He has not shown from the evidence that we can see any ability to get a political base of his own to be a counterweight to the more redistributive tendencies of the Nehru Gandhi dynasty. And that’s the sense that in somewhat cheeky way I was using the term overachiever.

Do you think he is just keeping the seat warm for Rahul Gandhi?

It increasingly appears to be that way. If that is true then it suggests that we shouldn’t really expect much to happen in the next two years.

Does the fiscal deficit of India worry you?

If you look at some shorter to medium term challenges, then things like fiscal deficit and the current account deficit are things to worry about. Again other things like the weak rupee, the weak FDI data, things that people tend to fixate at, but those at best are symptoms of a deeper structural problem. The deeper concern is the kind of reform that will require a major legislative agenda such as labour law reform for example to unlock our manufacturing sector. And managing the huge demographic dividend that we are going to get in the form of 300-400 million young people. They will have to be educated.

But is there a demographic dividend?

That’s the question. Will it become a demographic nightmare? Can you imagine the social chaos if you have all these kids just wandering around, not educated enough to get a job, what are they going to do? It’s a recipe for social disaster. That according to me is going to be real litmus test. If we are able to navigate that then I don’t see why we won’t be on track to again go back to 8- 9% economic growth. I want to remain optimistic at the end of the day.

(The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 6,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_reform-by-stealth-the-originalsin-of-1991-has-come-back-to-haunt-us_1724348)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

'You can shut the equity market, India would still be doing fine'

Have you ever heard someone call equity a short term investment class? Chances are no. “I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it… You can build a case for equities on a three year basis. But long term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it,” says Shankar Sharma, vice-chairman & joint managing director, First Global. In this freewheeling

interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Six months into the year, what’s your take on equities now?

Globally markets are looking terrible, particularly emerging markets. Just about every major country you can think of is stalling in terms of growth. And I don’t see how that can ever come back to the go-go years of 2003-2007. The excesses are going to take an incredible amount of time to work their way out. They are not even prepared to work off the excesses, so that’s the other problem.

Why do you say that?

If you look at the pattern in the European elections the incumbents lost because they were trying to push for austerity. And the more leftist parties have come to power. Now leftists are usually the more austere end of the political spectrum. But they have been voted to power, paradoxically, because they are promising less austerity. All the major nations in the world are democracies barring China. And that’s the whole problem. You can’t push through austerity that easily in a democracy, but that is what is really needed. Even China cannot push through austerity because of a powder-keg social situation. And I find it very strange when people criticise India for subsidies and all that. India is far less profligate than many nations including China.

Can you elaborate on that?

Every country has to subsidise, be it farm subsidies in the West or manufacturing subsidies in China, because ultimately whether you are a capitalist or a communist, people are people. They don’t necessarily change their views depending on which political ideology is at the centre. They ultimately want freebies and handouts. In a country like India, they don’t even want handouts they just want subsistence, given the level of poverty. The only thing that you can do with subsidies is to figure out how to control them. But a lot of it is really out of your control. If you have a global inflation in food prices or oil prices you are not increasing the quantum in volume terms of the subsidy. But because of price inflation, the number inflates. So why blame India? I find it absurd that the Financial Times or the Economist are perennially anti-India. They just isolate India and say that it has got wasteful expenditure programmes. A lot of countries hide things. India, unfortunately, is far more transparent in its reporting. It is easy to pick holes when you are transparent. China gives no transparency so people assume that whatever is inside the black box must be okay. That said, I firmly believe the UID program, when fully implemented, will make subsidies go lower by cutting out bogus recipients.

If increased austerity is not a solution, where does that leave us?

Increased austerity, while that is a solution, it is not achievable. If that is not possible what is the solution? You then have a continual stream of increasing debt in one form or the other, keep calling it a variety of names. But you just keep kicking the can down the road for somebody else to deal with it as long as the voter is happy. Given this, I don’t see how you can have any resurgence. Risk appetite is what drives equity markets. Otherwise you and I would be buying bonds all the time. In today’s environment and in the foreseeable future, we are overfed with risk. Where is the appetite to take more risk and go, buy equities?

So are you suggesting that people won’t be buying stocks?

Well you can get pretty good returns in fixed income. Instead of buying emerging-market stocks if you buy bonds of good companies, you can get 6-7% dollar yield, and if you leverage yourself two times or something, you are talking about annual returns of 14-15% dollar returns. You can’t beat that by buying equities, boss! Even if you did beat that by buying equities, let’s say you made 20%, it is not a predictable 20%, which has been my case for a long time against equities. Equities are a western fashion. I have always had this notion for many years that people buy equities because they like to be excited. It’s not just about the returns they make out of it: it is about the whole entertainment quotient attached to stock investing that drives investors. There is 24-hour television. Tickers. Cocktail discussions. Compared with that, bonds are so boring and uncool. Purely financially, shorn of all hype, equities have never been able to build a case for themselves on a ten-year return basis. You can build a case for equities on a three-year basis. But long-term investing is all rubbish, I have never believed in it.

So investing regularly in equities, doing SIPs, buying Ulips, doesn’t make sense?

I don’t buy the whole logic of long-term equity investing because equity investing comes with a huge volatility attached to it. People just say “equities have beaten bonds”. But even in India they have not. Also people never adjust for the volatility of equity returns. So if you make 15% in equity and let’s say, in a country like India, you make 10% in bonds – that’s about what you might have averaged over a 15-20 year period because in the 1990s we had far higher interest rates. Interest rates have now climbed back to that kind of level of 9-10%. Divide that by the standard deviation of the returns and you will never find a good case for equities over a long-term period. So equity is actually a short-term instrument. Anybody who tells you otherwise is really bluffing you. All the fancy graphs and charts are rubbish.

Are they?

Yes. They are all massaged with sort of selective use of data to present a certain picture because it’s a huge industry which feeds off it globally. So you have brokers like us. You have investment bankers. You have distributors. We all feed off this. Ultimately we are a burden on the investor, and a greater burden on society — which is also why I believe that the best days of financial services is behind us: the market simply won’t pay such high costs for such little value added. Whatever little return that the little guy gets is taken away by guys like us. How is the investor ever going to make money, adjusted for volatility, adjusted for the huge cost imposed on him to access the equity markets? It just doesn’t add up. The customer never owns a yacht. And separately, I firmly believe making money in the markets is largely a game of luck. Even the best investors, including Buffet, have a strike rate of no more than 50-60% right calls. Would you entrust your life to a surgeon with that sort of success rate?! You’d be nuts to do that. So why should we revere gurus who do just about as well as a coin-flipper. Which is why I am always mystified why so many fund managers are so arrogant. We mistake luck for competence all the time. Making money requires plain luck. But hanging onto that money is where you require skill. So the way I look at it is that I was lucky that I got 25 good years in this equity investing game thanks to Alan Greenspan who came in the eighties and pumped up the whole global appetite for risk. Those days are gone. I doubt if you are going to see a broad bull market emerging in equities for a while to come.

And this is true for both the developing and the developed world?

If anything it is truer for the developing world because as it is, emerging market investors are more risk-averse than the developed-world investors. We see too much of risk in our day to day lives and so we want security when it comes to our financial investing. Investing in equity is a mindset. That when I am secure, I have got good visibility of my future, be it employment or business or taxes, when all those things are set, then I say okay, now I can take some risk in life. But look across emerging markets, look at Brazil’s history, look at Russia’s history, look at India’s history, look at China’s history, do you think citizens of any of these countries can say I have had a great time for years now? That life has been nice and peaceful? I have a good house with a good job with two kids playing in the lawn with a picket fence? Sorry, boss, that has never happened.

And the developed world is different?

It’s exactly the opposite in the west. Rightly or wrongly, they have been given a lifestyle which was not sustainable, as we now know. But for the period it sustained, it kind of bred a certain amount of risk-taking because life was very secure. The economy was doing well. You had two cars in the garage. You had two cute little kids playing in the lawn. Good community life. Lots of eating places. You were bred to believe that life is going to be good so hence hey, take some risk with your capital.

The government also encouraged risk taking?

The government and Wall Street are in bed in the US. People were forced to invest in equities under the pretext that equities will beat bonds. They did for a while. Nevertheless, if you go back thirty years to 1982, when the last bull market in stocks started in the United States and look at returns since then, bonds have beaten equities. But who does all this math? And Americans are naturally more gullible to hype. But now western investors and individuals are now going to think like us. Last ten years have been bad for them and the next ten years look even worse. Their appetite for risk has further diminished because their picket fences, their houses all got mortgaged. Now they know that it was not an American dream, it was an American nightmare.

At the beginning of the year you said that the stock market in India will do really well…

At the beginning of the year our view was that this would be a breakaway year for India versus the emerging market pack. In terms of nominal returns India is up 13%. Brazil is down 3%. China is down, Russia is also down. The 13% return would not be that notable if everything was up 15% and we were up 25%. But right now, we are in a bear market and in that context, a 13-15% outperformance cannot be scoffed off at.

What about the rupee? Your thesis was that it will appreciate…

Let me explain why I made that argument. We were very bearish on China at the beginning of the year. Obviously when you are bearish on China, you have to be bearish on commodities. When you are bearish on commodities then Russia and Brazil also suffer. In fact, it is my view that Russia, China, Brazil are secular shorts, and so are industrial commodities: we can put multi-year shorts on them. So that’s the easy part of the analysis. The other part is that those weaknesses help India because we are consumers of commodities at the margin. The only fly in the ointment was the rupee. I still maintain that by the end of the year you are going to see a vastly stronger rupee. I believe it will be Rs 44-45 against the dollar. Or if you are going to say that is too optimistic may be Rs 47-48. But I don’t think it’s going to be Rs 60-65 or anything like that. At the beginning of the year our view that oil prices will be sharply lower. That time we were trading at around $105-110 per barrel. Our view was that this year we would see oil prices of around $65-75. So we almost got to $77 per barrel (Nymex). We have bounced back a bit. But that’s okay. Our view still remains that you will see oil prices being vastly lower this year and next year as well, which is again great news for India. Gold imports, which form a large part of the current account deficit, shorn of it, we have a current account deficit of around 1.5% of the GDP or maybe 1%. We imported around $60 billion or so of gold last year. Our call was that people would not be buying as much gold this year as they did last year. And so far the data suggests that gold imports are down sharply.

So there is less appetite for gold?

Yes. In rupee terms the price of gold has actually gone up. So there is far less appetite for gold. I was in Dubai recently which is a big gold trading centre. It has been an absolute massacre there with Indians not buying as much gold as they did last year. Oil and gold being major constituents of the current account deficit our argument was that both of those numbers are going to be better this year than last year. Based on these facts, a 55/$ exchange rate against the dollar is not sustainable in my view. The underlyings have changed. I don’t think the current situation can sustain and the rupee has to strengthen. And strengthen to Rs 44, 45 or 46, somewhere in that continuum, during the course of the year. Imagine what that does to the equity market. That has a big, big effect because then foreign investors sitting in the sidelines start to play catch-up.

Does the fiscal deficit worry you?

It is not the deficit that matters, but the resultant debt that is taken on to finance the deficit. India’s debt to GDP ratio has been superb over the last 8-9 years. Yes, we have got persistent deficits throughout but our debt to GDP ratio was 90-95% in 2003, that’s down to maybe 65% now. So explain that to me? The point is that as long as the deficit fuels growth, that growth fuels tax collections, those tax collections go and give you better revenues, the virtuous cycle of a deficit should result in a better debt to GDP situation. India’s deficit has actually contributed to the lowering of the debt burden on the national exchequer. The interest payments were 50% of the budgetary receipts 7-8 years back. Now they are about 32-33%. So you have basically freed up 17% of the inflows and this the government has diverted to social schemes. And these social schemes end up producing good revenues for a lot of Indian companies. The growth for fast-moving consumer goods, mobile telephony, two wheelers and even Maruti cars, largely comes from semi-urban, semi-rural or even rural India.

What are you trying to suggest?

This growth is coming from social schemes being run by the government. These schemes have pushed more money in the hands of people. They go out and consume more. Because remember that they are marginal people and there is a lot of pent-up desire to consume. So when they get money they don’t actually save it, they consume it. That has driven the bottomlines of all FMCG and rural serving companies. And, interestingly, rural serving companies are high-tax paying companies. Bajaj Auto, Hindustan Lever or ITC pay near-full taxes, if not full taxes. This is a great thing because you are pushing money into the hands of the rural consumer. The rural consumer consumes from companies which are full taxpayers. That boosts government revenues. So if you boost consumption it boosts your overall fiscal situation. It’s a wonderful virtuous cycle — I cannot criticise it at all. What has happened in past two years is not representative. It is only because of the higher oil prices and food prices that the fiscal deficit has gone up.

What is your take on interest rates?

I have been very critical of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) policies in the last two years or so. We were running at 8-8.5% economic growth last year. Growth, particularly in the last two or three years, has been worth its weight in gold. In a global economic boom, an economic growth of 8%, 7% or 9% doesn’t really matter. But when the world is slowing down, in fact growth in large parts of the world has turned negative, to kill that growth by raising the interest rate is inhuman. It is almost like a sin. And they killed it under the very lofty ideal that we will tame inflation by killing growth. But if you have got a matriculation degree, you will understand that India’s inflation has got nothing to do with RBI’s policies. Your inflation is largely international commodity price driven. Your local interest rate policies have got nothing to do with that. We have seen that inflation has remained stubbornly high no matter what Mint Street has done. You should have understood this one commonsensical thing. In fact, growth is the only antidote to inflation in a country like India. When you have economic growth, average salaries and wages, kind of lead that. So if your nominal growth is 15%, you will 10-20% salary and wage hikes – we have seen that in the growth years in India. Then you have more purchasing power left in the hands of the consumer to deal with increased price of dal or milk or chicken or whatever it is. If the wage hikes don’t happen, you are leaving less purchasing power in the hands of people. And wage hikes won’t happen if you have killed economic growth. I would look at it in a completely different way. The RBI has to be pro-growth because they no control of inflation.

So they basically need to cut the repo rate?

They have to.

But will that have an impact? Because ultimately the government is the major borrower in the market right now…

Look, again, this is something that I said last year — that it is very easy to kill growth but to bring it back again is a superhuman task because life is only about momentum. The laws of physics say that you have to put in a lot of effort to get a stalled car going, yaar. But if it was going at a moderate pace, to accelerate is not a big issue. We have killed that whole momentum. And remember that 5-6%, economic growth, in my view, is a disastrous situation for a country like India. You can’t say we are still growing. 8% was good. 9% was great. But 4-5% is almost stalling speed for an economy of our kind. So in my view the car is at a standstill. Now you need to be very aggressive on a variety of fronts be it government policy or monetary policy.

What about the government borrowings?

The government’s job has been made easy by the RBI by slowing down credit growth. There are not many competing borrowers from the same pool of money that the government borrows from. So far, indications are that the government will be able to get what it wants without disturbing the overall borrowing environment substantially. Overall bond yields in India will go sharply lower given the slowdown in credit growth. So in a strange sort of way the government’s ability to borrow has been enhanced by the RBI’s policy of killing growth. I always say that India is a land of Gods. We have 33 crore Gods and Goddesses. They find a way to solve our problems.

So how long is it likely to take for the interest rates to come down?

The interest rate cycle has peaked out. I don’t think we are going to see any hikes for a long time to come. And we should see aggressive cuts in the repo rate this year. Another 150 basis points, I would not rule out. Manmohan Singh might have just put in the ears of Subbarao that it’s about time that you woke up and smelt the coffee. You have no control over inflation. But you have control over growth, at least peripherally. At least do what you can do, instead of chasing after what you can’t do.

Manmohan Singh in his role as a finance minister is being advised by C Rangarajan, Montek Singh Ahulwalia and Kaushik Basu. How do you see that going?

I find that economists don’t do basic maths or basic financial analysis of macro data. Again, to give you the example of the fiscal deficit and I am no economist. All I kept hearing was fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit, fiscal deficit. I asked my economist: screw this number and show me how the debt situation in India has panned out. And when I saw that number, I said: what are people talking about? If your debt to GDP is down by a third, why are people focused on the intermediate number? But none of these economists I ever heard them say that India’s debt to GDP ratio is down. I wrote to all of them, please, for God’s sake, start talking about it. Then I heard Kaushik Basu talk about it. If a fool like me can figure this out, you are doing this macro stuff 24×7. You should have had this as a headline all the time. But did you ever hear of this? Hence I am not really impressed who come from abroad and try to advise us. But be that as it may it is better to have them than an IAS officer doing it. I will take this.

You talked about equity being a short-term investment class. So which stocks should an Indian investor be betting his money right now?

I am optimistic about India within the context of a very troubled global situation. And I do believe that it’s not just about equity markets but as a nation we are destined for greatness. You can shut down the equity markets and India would still be doing what it is supposed to do. But coming from you I find it a little strange…

I have always believed that equity markets are good for intermediaries like us. And I am not cribbing. It’s been good to me. But I have to be honest. I have made a lot of money in this business doesn’t mean all investors have made a lot of money. At least we can be honest about it. But that said, I am optimistic about Indian equities this year. We will do well in a very, very tough year. At the beginning of the year, I thought we will go to an all-time high. I still see the market going up 10-15% from the current levels.

So basically you see the Sensex at around 19,000?

At the beginning of the year, you would have taken it when the Sensex was at 15,000 levels. Again, we have to adjust our sights downwards. A drought angle has come up which I think is a very troublesome situation. And that’s very recent. In light of that I do think we will still do okay, it will definitely not be at the new high situation.

What stocks are you bullish on?

We had been bearish on infrastructure for a very long time, from the top of the market in 2007 till the bottom in December last year. We changed our view in December and January on stocks like L&T, Jaiprakash Industries and IVRCL. Even though the businesses are not, by and large, of good quality — I am not a big believer in buying quality businesses. I don’t believe that any business can remain a quality business for a very long period of time. Everything has a shelf life. Every business looks quality at a given point of time and then people come and arbitrage away the returns. So there are no permanent themes. And we continue to like these stocks. We have liked PSU banks a lot this year, because we see bond yields falling sharply this year.

Aren’t bad loans a huge concern with these banks?

There is a company in Delhi — I won’t name it. This company has been through 3-4 four corporate debt restructurings. It is going to return the loans in the next year or two. If this company can pay back, there is no problem of NPAs, boss. The loans are not bogus loans without any asset backing. There are a lot of assets. At the end of every large project there is something called real estate. All those projects were set up with Rs 5 lakh per acre kind of pricing for land. Prices are now Rs 50 lakh per acre or Rs 1 crore or Rs 1.5 crore per acre. If nothing else, dismantle the damn plant, you will get enough money from the real estate to repay the loans of the public sector banks. So I am not at all concerned on the debt part. If the promoter finds that is going to happen, he will find some money to pay the bank and keep the real estate.

On the same note, do you see Vijay Mallya surviving?

100% he will survive. And Kingfisher must survive, because you can’t only have crap airlines like Jet and British Airways. If God ever wanted to fly on earth, he would have flown Kingfisher.

So he will find the money?

Of course! At worst, if United Spirits gets sold, that’s a stock that can double or triple from here. I am very optimistic about United Spirits. Be it the business or just on the technical factor that if Mallya is unable to repay and his stake is put up for sale, you will find bidders from all over the world converging.

So you are talking about the stock and not Mallya?

Haan to Mallya will find a way to survive. Indian promoters are great survivors. We as a nation are great survivors.

How do you see gold?

I don’t have a strong view on gold. I don’t understand it well enough to make big call on gold, even though I am an Indian. One thing I do know is that our fascination with gold has very strong economic moorings. We should credit Indians for having figured out what is a multi century asset class. Indians have figured out that equities are a fashionable thing meant for the Nariman Points of the world, but for us what has worked for the last 2000 years is what is going to work for the next 2000 years.

What about the paper money system, how do you see that?

I don’t think anything very drastic where the paper money system goes out of the window and we find some other ways to do business with each. Or at least I don’t think it will happen in my life time. But it’s a nice cute notion to keep dreaming about.

At least all the gold bugs keep talking about the collapse of the paper money system…

I know. I don’t think it’s going to happen. But I don’t think that needs to happen for gold to remain fashionable. I don’t think the two things are necessarily correlated. I think just the notion of that happening is good enough to keep gold prices high.

(A slightly smaller version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on July 31,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_you-can-shut-the-equity-market-india-would-still-be-doing-fine_1721939)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])