Vivek Kaul

It is that time of the year when newspapers, magazines and websites get around to making top 10 lists on various things in the year that was. So here is my list for the top 10 books in the Indian non fiction category (The books appear in a random order).

Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles – Ruchir Sharma (Penguin/Allen Lane -Rs 599)

The book is based around the notion that sustained economic growth cannot be taken for granted.

Only six countries which are classified as emerging markets by the western world have grown at the rate of 5 percent or more over the last 40 years. Only two of these countries, i.e. Taiwan and South Korea, have managed to grow at 5 percent or more for the last 50 years.

The basic point being that the economic growth of countries falters more often than not. “India is already showing some of the warning signs of failed growth stories, including early-onset of confidence,” Sharma writes in the book.

When Sharma said this in what was the first discussion based around the book on an Indian television channel, Montek Singh Ahulwalia, the deputy chairman of the planning commission, did not agree. Ahulwalia, who was a part of the discussion, insisted that a 7 percent economic growth rate was a given. Turned out it wasn’t. The economic growth in India has now slowed down to around 5.5 percent.

Sharma got his timing on the India economic growth story fizzling out absolutely right.

The last I met him in November he told me that the book had sold around 45,000 copies in India. For a non fiction book which doesn’t tell readers how to lose weight those are very good numbers. (You can read Sharma’s core argument here).

In the Company of a Poet – Gulzar In Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir(Rainlight/Rupa -Rs 495)

There is very little quality writing available on the Hindi film industry. Other than biographies on a few top stars nothing much gets written. Gulzar is one exception to this rule. There are several biographies on him, including one by his daughter Meghna. But all these books barely look on the creative side of him. What made Sampooran Singh Kalra, Gulzar? How did he become the multifaceted personality that he did?

There are very few individuals who have the kind of bandwidth that Gulzar does. Other than directing Hindi films, he has written lyrics, stories, screenplays as well as dialogues for them. He has been a documentary film maker as well, having made documentaries on Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. He is also a poet and a successful short story writer. On top of all this he has translated works from Bangla and Marathi into Urdu/Hindi.

In this book, Nasreen Munni Kabir talks to Gulzar and the conversations bring out how Sampooran Singh Kalra became Gulzar. Gulzar talks with great passion about his various creative pursuits in life. From writing the superhit kajrare to what he thinks about Tagore’s English translations. If I had a choice of reading only one book all through this year, this would have to be it.

Durbar – Tavleen Singh (Hachette – Rs 599)

Some of the best writing on the Hindi film industry that I have ever read was by Sadat Hasan Manto. Manto other than being the greatest short writer of his era also wrote Hindi film scripts and hence had access to all the juicy gossip. The point I am trying to make is that only an insider of a system can know how it fully works. But of course he may not be able to write about it, till he is a part of the system. Manto’s writings on Hindi films and its stars in the 1940s only happened once he had moved to Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. When he became an outsider he chose to reveal all that he had learnt as an insider.

Tavleen Singh’s Durbar is along similar lines. As a good friend of Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, during the days when both of them had got nothing to do with politics, she had access to them like probably no other journalist did. Over the years she fell out first with Sonia and then probably with Rajiv as well.

Durbar does have some juicy gossip about the Gandhi family in the seventies. My favourite is the bit where Sonia and Maneka Gandhi had a fight over dog biscuits. But it would be unfair to call it just a book of gossip as some Delhi based reviewers have.

Tavleen Singh offers us some fascinating stuff on Operation Bluestar and the chamchas surrounding the Gandhi family and how they operated. The part that takes the cake though is the fact that Ottavio Quattrocchi and his wife were very close to Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, despite Sonia’s claims now that she barely knew them. If there is one book you should be reading to understand how the political city of Delhi operates and why that has landed India in the shape that it has, this has to be it.

The Sanjay Story – Vinod Mehta (Harper Collins – Rs 499).Technically this book shouldn’t be a part of the list given that it was first published in 1978 and has just been re-issued this year. But this book is as important now as it was probably in the late 1970s, when it first came out.

Mehta does a fascinating job of unravelling the myth around Sanjay Gandhi and concludes that he was the school boy who never grew up.

“Intellectually Sanjay had never encountered complexity. He was an I.S.C and at that educational level you are not likely to learn (through your educational training) the art of resolving involved problems… He himself confessed in 1976 that possibly his strongest intellectual stimulation came from comics,” writes Mehta.

The book goes into great detail about the excesses of the emergency era. From nasbandi to the censors taking over the media, it says it all. Sanjay was not a part of the government in anyway but ruled the country. And things are similar right now!

Patriots and Partisans – Ramachandra Guha (Penguin/Allen Lane – Rs 699)

The trouble with most Delhi based Indian intellectuals is that they have very strong ideologies. There sensitivities are either to the extreme left or the extreme right, and those in the middle are essentially stooges of the Congress party. Given that, India has very few intellectuals who are liberal in the strictest of the terms. Ramachandra Guha is one of them, his respect for Nehru and his slight left leanings notwithstanding. And what of course helps is the fact that he lives in Bangalore and not in Delhi.

His new book Patriots and Partisans is a collection of fifteen essays which largely deal with all that has and is going wrong in India. One of the finest essays in the book is titled A Short History of Congress Chamchagiri. This essay on its own is worth the price of the book. Another fantastic essay is titled Hindutva Hate Mail where Guha writes about the emails he regularly receives from Hindutva fundoos from all over the world.

His personal essays on the Oxford University Press, the closure of the Premier Book Shop in Bangalore and the Economic and Political Weekly are a pleasure to read. If I was allowed only to read two non fiction books this year, this would definitely be the second book. (Read my interview with Ramachandra Guha here).

Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India – Vivek Dehejia and Rupa Subramanya (Vintage Books Random House India – Rs 399)

This little book running into 185 pages was to me the surprise package of this year. The book is along the lines of international bestsellers like Freakonomics and The Undercover Economist. It uses economic theory and borrows heavily from the emerging field of behavioural economics to explain why India and Indians are the way they are.

Other than trying to explain things like why are Indians perpetually late or why do Indian politicians prefer wearing khadi in public and jeans in their private lives, the book also delves into fairly serious issues.

Right from explaining why so many people in Mumbai die while crossing railway lines to explaining why Nehru just could not see the obvious before the 1962 war with China, the book tries to explain a broad gamut of issues.

But the portion of the book that is most relevant right now given the current protests against the rape of a twenty year old woman in Delhi, is the one on the ‘missing women’ of India. Women in India are killed at birth, after birth and as they grow up is the point that the book makes.

My only complain with the book is that I wish it could have been a little longer. Just as I was starting to really enjoy it, the book ended. (Read my interview with Vivek Dehejia here)

Taj Mahal Foxtrot – The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age – Naresh Fernandes (Roli Books – Rs 1295)

Bombay (Mumbai as it is now known as) really inspires people who lives here and even those who come from the outside to write about it. Only that should explain the absolutely fantastic books that keep coming out on the city (No one till date has been able to write a book as grand as Shantaram set in Delhi or a book with so many narratives like Maximum City set in Bangalore).

This year’s Bombay book written by a Mumbaikar has to be Naresh Fernades’s Taj Mahal Foxtrot.

The book goes into the fascinating story of how jazz came to Bombay. It talks about how the migrant musicians from Goa came to Bombay to make a living and became its most famous jazz artists. And they had delightful names like Chic Chocolate and Johnny Baptist. The book also goes into great detail about how many black American jazz artists landed up in Bombay to play and take the city by storm. The grand era that came and went.

While growing up I used to always wonder why did Hindi film music of the 1950s and 1960s sound so Goan. And turns out the best music directors of the era had music arrangers who came belonged to Goa. The book helped me set this doubt to rest.

The Indian Constitution – Madhav Khosla (Oxford University Press – Rs 195)

I picked up this book with great trepidation. I knew that the author Madhav Khosla was a 27 year old. And I did some back calculation to come to the conclusion that he must have been probably 25 years old when he started writing the book. And that made me wonder, how could a 25 year old be writing on a document as voluminous as the Indian constitution is?

But reading the book set my doubts to rest, proving once again, that age is not always related to good scholarship. What makes this book even more remarkable is the fact that in 165 pages of fairly well spaced text, Khosla gives us the history, the present and to some extent the future of the Indian constitution.

His discussion on caste being one of the criteria on the basis of which backwardness is determined in India makes for a fascinating read. Same is true for the section on the anti defection law that India has and how it has evolved over the years.

Lucknow Boy – Vinod Mehta (Penguin – Rs 499)

One of my favourite jokes on Lucknow goes like this. An itinerant traveller gets down from the train on the Lucknow Railway station and lands into a beggar. The beggar asks for Rs 5 to have a cup of tea. The traveller knows that a cup of tea costs Rs 2.50. He points out the same to the beggar.

“Aap nahi peejiyega kya? (Won’t you it be having it as well?),” the beggar replies. The joke reveals the famous tehzeeb of Lucknow.

Vinod Mehta’s Lucknow Boy starts with his childhood days in Lucknow and the tehzeeb it had and it lost over the years. The first eighty pages the book are a beautiful account of Mehta’s growing up years in the city and how he and his friends did things with not a care in the world. Childhood back then was about being children, unlike now.

The second part of the book has Mehta talking about his years as being editor of various newspapers and magazines. This part is very well written and has numerous anecdotes like any good autobiography should, but I liked the book more for Mehta’s description of his carefree childhood than his years dealing with politicians, celebrities and other journalists.

Behind the Beautiful Forevers – Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity – Katherine Boo (Penguin – Rs 499)

As I said a little earlier Mumbai inspires books like no other city in India does. A fascinating read this year has been Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. Indians are typical apprehensive about foreigners writing on their cities. But some of the best Mumbai books have been written by outsiders. Gregory David Roberts who wrote Shantaram arrived in Mumbai having escaped from an Australian prison. There is no better book on Mumbai than Shantaram. The same is true about Suketu Mehta and Maximum City. Mehta was a Bombay boy who went to live in America and came back to write the book that he did.

Boo’s book on Mumbai is set around a slum called Annawadi. She spent nearly three years getting to know the people well enough to write about them. Hence stories of individuals like Kalu, Manju, Abdul, Asha and Sunil, who live in the slum come out very authentic. The book more than anything else I have read on Mumbai ( with the possible exception of Shantaram) brings out the sheer grit that it takes to survive in a city like Mumbai.

So that was my list for what I think were the top 10 Indian non fiction books for the year. One book that you should definitely avoid reading is Chetan Bhagat’s What Young India Wants. Why would you want to read a book which says something like this?

Money spent on bullets doesn’t give returns, money spent on better infrastructure does… In this technology-driven age, do you really think America doesn’t have the information or capability to launch an attack against India? But they don’t want to attack us. They have much to gain from our potential market for American products and cheap outsourcing. Well let’s outsource some of our defence to them, make them feel secure and save money for us. Having a rich, strong friend rarely hurt anyone.

And if that is not enough let me share what Bhagat thinks would happen if women weren’t around. “There would be body odour, socks on the floor and nothing in the fridge to eat.” Need I say anything else?

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 26, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

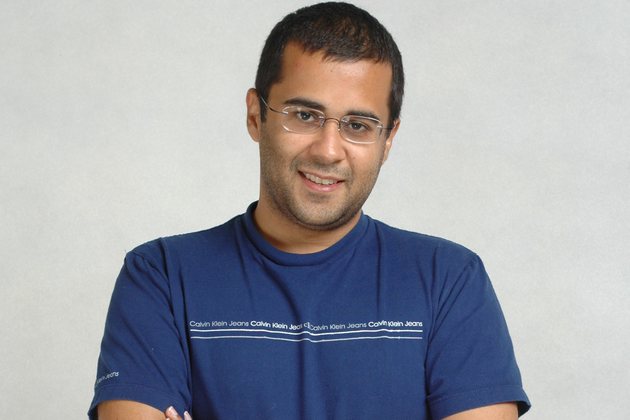

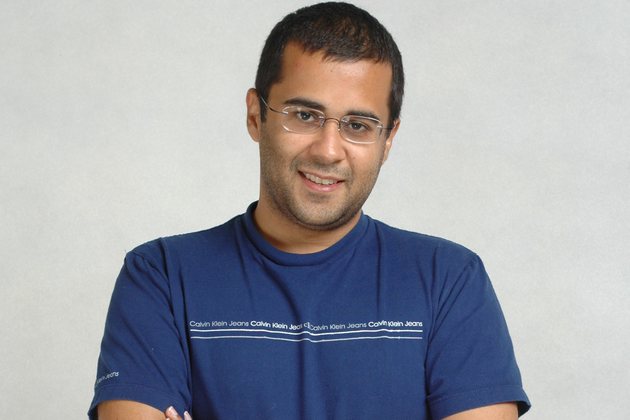

Chetan Bhagat

Of 9% economic growth and Manmohan’s pipedreams

Vivek Kaul

Shashi Tharoor before he decided to become a politician was an excellent writer of fiction. It is rather sad that he hasn’t written any fiction since he became a politician. A few lines that he wrote in his book Riot: A Love Story I particularly like. “There is not a thing as the wrong place, or the wrong time. We are where we are at the only time we have. Perhaps it’s where we’re meant to be,” wrote Tharoor.

India’s slowing economic growth is a good case in point of Tharoor’s logic. It is where it is, despite what the politicians who run this country have to say, because that’s where it is meant to be.

The Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in his independence-day speech laid the blame for the slowing economic growth in India on account of problems with the global economy as well as bad monsoons within the country. As he said “You are aware that these days the global economy is passing through a difficult phase. The pace of economic growth has come down in all countries of the world. Our country has also been affected by these adverse external conditions. Also, there have been domestic developments which are hindering our economic growth. Last year our GDP grew by 6.5 percent. This year we hope to do a little better…While doing this, we must also control inflation. This would pose some difficulty because of a bad monsoon this year.”

So basically what Manmohan Singh was saying that I know the economic growth is slowing down, but don’t blame me or my government for it. Singh like most politicians when trying to explain their bad performance has resorted to what psychologists calls the fundamental attribution bias.

As Vivek Dehejia an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, told me in a recent interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) “Fundamentally attribution bias says that we are more likely to attribute to the other person a subjective basis for their behaviour and tend to neglect the situational factors. Looking at our own actions we look more at the situational factors and less at the idiosyncratic individual subjective factors.”

In simple English what this means is that when we are analyzing the performance of others we tend to look at the mistakes that they made rather than the situational factors. On the flip side when we are trying to explain our bad performance we tend to blame the situational factors more than the mistakes that we might have made.

So in Singh’s case he has blamed the global economy and the deficient monsoon for the slowing economic growth. He also blamed his coalition partners. “As far as creating an environment within the country for rapid economic growth is concerned, I believe that we are not being able to achieve this because of a lack of political consensus on many issues,” Singh said.

Each of these reasons highlighted by Singh is a genuine reason but these are not the only reasons because of which economic growth of India is slowing down. A major reason for the slowing down of economic growth is the high interest rates and high inflation that prevails. With interest rates being high it doesn’t make sense for businesses to borrow and expand. It also doesn’t make sense for you and me to take loans and buy homes, cars, motorcycles and other consumer durables.

The question that arises here is that why are banks charging high interest rates on their loans? The primary reason is that they are paying high interest rate on their deposits.

And why are they paying a high interest rate on their deposits? The answer lies in the fact that banks have been giving out more loans than raising deposits. Between December 30, 2011 and July 27, 2012, a period of nearly seven months, banks have given loans worth Rs 4,16,050 crore. During the same period the banks were able to raise deposits worth Rs 3,24,080 crore. This means an incremental credit deposit ratio of a whopping 128.4% i.e. for every Rs 100 raised as deposits, the banks have given out loans of Rs 128.4.

Thus banks have not been able to raise as much deposits as they are giving out loans. The loans are thus being financed out of deposits raised in the past. What this also means is that there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits and hence banks have had to offer higher interest rates than normal to raise this money.

So the question that crops up next is that why there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits? This as I have said more than few times in the past is because the expenditure of the government is much more than its earnings.

The fiscal deficit of the government or the difference between what it earns and what it spends has been going up, over the last few years. For the financial year 2007-2008 the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. It went up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for financial year 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore.

This difference is made up for by borrowing. When the borrowing needs of the government go through the roof it obviously leaves very little on the table for the banks and other private institutions to borrow, which in turn means that they have to offer higher interest rates to raise deposits. Once they offer higher interest rates on deposits, they have to charge higher interest rate on loans.

A higher interest rate scenario slows down economic growth as companies borrow less to expand their businesses and individuals also cut down on their loan financed purchases. This impacts businesses and thus slows down economic growth.

The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum. One of the programmes that benefits from the government subsidy is Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The scheme guarantees 100 days of work to adults in any rural household. While this is a great short term fix it really is not a long term solution. If creating economic growth was as simple as giving away money to people and asking them to dig holes, every country in the world would have practiced it by now.

As Raghuram Rajan, who is taking over as the next Chief Economic Advisor of the government of India, told me in an interview I did for DNA a couple of years back “The National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS, another name for MGNREGA), if appropriately done it is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key.”

But the Manmohan Singh led United Progressive Alliance seems to be looking at the employment guarantee scheme as a long term solution rather than a short term fix. This has led to burgeoning wage inflation over the last few years in rural areas.

As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “The wages guaranteed by MGNREGA pushed rural wage inflation up to 15 percent in 2011”.

Also as more money in the hands of rural India chases the same number of goods it has led to increased price inflation as well. Consumer price inflation currently remains over 10%. The most recent wholesale price index inflation number fell to 6.87% for the month of July 2012, from 7.25% in June. But this experts believe is a short term phenomenon and inflation is expected to go up again in the months to come.

As Ruchir Sharma wrote in a column that appeared yesterday in The Times of India “For decades India’s place in the rankings of nations by inflation rates also held steady, somewhere between 78 and 98 out of 180. But over the past couple of years India’s inflation rate is so out of whack that its ranking has fallen to 151. No nation has ever managed to sustain rapid growth for several decades in the face of high inflation. It is no coincidence that India is increasingly an outlier on the fiscal front as well with the combined central and state government deficits now running four times higher than the emerging market average of 2%.” (You can read the complete column here).

So to get economic growth back on track India has to control inflation. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been trying to control inflation by keeping the repo rate, or the rate at which it lends to banks, at a high level. One school of thought is that once the RBI starts cutting the repo rate, interest rates will fall and economic growth will bounce back.

That is specious argument at best. Interest rates are not high because RBI has been keeping the repo rate high. The repo rate at best acts as an indicator. Even if the RBI were to cut the repo rate the question is will it translate into interest rate on loans being cut by banks? I don’t see that happening unless the government clamps down on its borrowing. And that will only happen if it’s able to control the subsidies.

The fiscal deficit for the current financial year 2012-2013 has been estimated at Rs Rs Rs 5,13,590 crore. I wouldn’t be surprised if the number even touches Rs 600,000 crore. The oil subsidy for the year was set at Rs 43,580 crore. This has already been exhausted. Oil prices are on their way up and brent crude as I write this is around $115 per barrel. The government continues to force the oil marketing companies to sell diesel, LPG and kerosene at a loss. The diesel subsidy is likely to continue given that with the bad monsoon farmers are now likely to use diesel generators to pump water to irrigate their fields. With food inflation remaining high the food subsidy is also likely to go up.

The heart of India’s problem is the huge fiscal deficit of the government and its inability to control it. As Sharma points out in Breakout Nations “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period…If the government continues down this path India, may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

These details Manmohan Singh couldn’t have mentioned in his speech. But he tried to project a positive picture by talking about the planning commission laying down measures to ensure a 9% rate of growth. The one measure that the government needs to start with is to cut down the fiscal deficit. And the probability of that happening is as much as my writing having more readers than that of Chetan Bhagat. Hence India’s economic growth is at a level where it is meant to be irrespective for all the explanations that Manmohan Singh gave us and the hope he tried to project in his independence-day speech.

But then you can’t stop people from dreaming in broad daylight. Even Manmohan Singh! As the great Mirza Ghalib who had a couplet for almost every situation in life once said “hui muddat ke ghalib mar gaya par yaad aata hai wo har ek baat par kehna ke yun hota to kya hota?”

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 16,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/of-9-economic-growth-and-manmohans-pipedreams-419371.html)

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

Why Chetan Bhagat sells, despite the mediocrity tag

Vivek Kaul

It was sometime in late 2005 or early 2006 my memory fails me, when I ran into Chetan Bhagat at the Crossword book store at Juhu in Mumbai. Those were the days when he was still an investment banker based out of Hong Kong. He was passing by the book store and had decided to drop in to check how his second book was selling.

One Night At the Call Centre had just come out and was number one on the bestsellers list. He hadn’t become a celebrity as he is now and people took some time to recognize him. He sat down and started signing books that fans brought to him.

I must confess that I was a fan of his writing back then and had loved reading Five Point Someone (On a totally different note I was even a fan of Himesh Reshammiya for a brief period). So I promptly bought his two books and got them autographed from him.

Bhagat’s first book Five Point Someone wasn’t a literary phenomenon but had broken all sales records. The story was set in IIT Delhi and had a certain charm to it. Bhagat must have borrowed a lot from his own life and that honesty reflected in the book.

But Bhagat had had a tough time finding a publisher for his first book. Bhagat had to do the rounds of several publishers before Rupa latched onto Five Point Someone. As one of the editors who had rejected his manuscript wrote in the Open magazine “He later went to a rival firm and became a publishing sensation overnight, and to this day, our boss complains bitterly that he missed out on the biggest bestseller of the decade because he went by the judgement of three Bengali women—a flawed demographic, if there ever was one!” (You can read the complete piece here).

In the CD that accompanied the manuscript of Five Point Someone Bhagat had also elaborated on a marketing plan. The M word did not go down well with the female Bengali editor and as she remarked in the Open “A marketing strategy that would ensure the book became an instant bestseller…If only he had written his manuscript with half the dedication he had put into his marketing plan! “

Hence, the so called “sophisticated” people at the biggest Indian publishing houses missed out on India’s bestselling English author primarily because his writing wasn’t literary enough. ,Bhagat eventually did find a publisher and the rest as they say is history.

The day I ran into Bhagat was a Sunday and I came back home and finished reading One Night At a Call Centre in a few hours. I found the book pretty boring and at the same time got a feeling that the author had decided to put together a quickie to cash in on the success of his first book. But then I was probably in a minority who thought that way. The book became an even bigger success than Five Point Someone. His next book was The Three Mistakes of My Life. I couldn’t read the book beyond the first twenty pages. His next two books, Two States and Revolution 2020, I haven’t attempted to read till date.

Very recently his sixth book and his first work of non-fiction What Young India Wants has come out. The book is essentially a collection of his newspaper columns. It is also an extension of his attempts over the last few years at building a more serious image for himself of someone who not only writes popular books but also understands the pulse and paradoxes of Young India.

As the Open magazine puts it “Years spent as a pariah in literary circles seem to have caught up with Chetan Bhagat, India’s largest-selling fiction writer. He’s excited that he’s moved on to some “meaningful” writing as well. “The charge against me is I’m too flippant,” he says. The author, who sees himself as a spokesperson for India’s youth, has just launched his latest book, What Young India Wants, a compilation of his essays on issues troubling the country, mainly corruption and discrimination based on caste and religion. He’s hoping that it will gain him some credibility as a writer.”

So what does Bhagat come up in his tour de force? Here are some samples.

On Pakistan:

“More than anything else, we want to teach Pakistan a lesson. We want to put them in their place. Bashing Pakistan is considered patriotic. It also makes for great politics.”

On Voting:

“We have to consider only one criterion—is he or she a good person?”

On Defence:

Money spent on bullets doesn’t give returns, money spent on better infrastructure does…In this technology-driven age, do you really think America doesn’t have the information or capability to launch an attack against India? But they don’t want to attack us. They have much to gain from our potential market for American products and cheap outsourcing. Well let’s outsource some of our defence to them, make them feel secure and save money for us. Having a rich, strong friend rarely hurt anyone

On Women: (Rajyasree Sen hope you are reading this):

“There would be body odour, socks on the floor and nothing in the fridge to eat,” writes Bhagat on what would happen if women weren’t around.

On Self Promotion:

“I had for years wanted to create more awareness for a better India. Wasn’t now the time to do it with full gusto?”

The book like other Bhagat books presents a very simplistic vision of the world that we live in and is accompanied by some pretty ordinary writing. “What young India wants is meri naukri and meri chokri,” Bhagat said while promoting the book. Bhagat also comes up with some preposterous solutions like the one where he talks about outsourcing India’s defence needs to America. Really?

At the same time the book stinks of self promotion. In interviews that Bhagat has given after the book came out he continues to refer himself as destiny’s child.

Thus it’s not surprising that Bhagat has come in for a barrage of criticism for his overtly simplistic views and his unabashed attempts at promoting himself. “Bhagat is not a thinker. He is our great ‘unthinker’, as sure a representative of heedless ‘new India’ as the khadi-clad politician is of old India,” wrote Shougat Dasgupta in Tehalka. (You can read the complete piece here).

The criticism notwithstanding Bhagat’s books sell like hot cakes. “His publishers, Rupa & Co., are counting on it. Rupa, which has brought out all of Bhagat’s novels since Five Point Someone in 2004, says that 500,000 copies of an initial print run of 575,000 were sold to retailers in a day, and booksellers have already begun to place repeat orders,” reports the Mint.

Given that there must be something right about them. The answer lies in the fact that the mass market is not intellectual. It’s mediocre. It would rather prefer the movies of Salman Khan than an Anurag Kashyap. It would rather go and watch a mindless Rowdy Rathore rather than a Gangs of Wasseypur, which demands attention from the viewer. It would rather watch a Kyunki Saans Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi than the History channel.

The mass market likes stuff which is not too heavy. Chetan Bhagat fulfills that need. There has always been space for the kind of mindless and simple stuff that Bhagat writes. How else do you explain the success of the Mills & Boons series? Also in a country like India where people are just about starting to learn English, it’s easier for them to understand a Chetan Bhagat than a Salman Rushdie or even a much easier Jeffrey Archer for that matter.

Bhagat’s writing is thus initiating people into reading. And in that sense it’s a good thing. Let me give a personal example to elaborate on this. Recently I started listening to Hindustani Classical music, more than 25 years after I first started listening to music. My taste has evolved the years. I started with the trashy Hindi film music of the 1980s, moved onto the Hindi film music of the fifties and the sixties, then went into Ghazals (which had its own cycle. First Jagjit Singh, then came Ghulam Ali, then Mehdi Hasan and finally came the likes of Begum Akhtar) and so on. It took me almost 25 years to start listening to Hindustani classical music. Maybe I was slower than the usual. But the point is that nobody starts of listening to Hindustani classical music from day one. We have to go through our share of “crappy” music to arrive at that. If I hadn’t heard the crappy music of the 1980s, I wouldn’t be listening to Ustad Bismillah Khan today.

Similarly readers who start reading books with Chetan Bhagat are likely to move onto much better stuff over the years. In that sense Bhagat’s writing is a necessary evil. The entire market for Indian writing in English has expanded since Chetan Bhagat started writing. Before that Indian writing in English did not appeal to the average Indian. Now it does.

It would also help them reach a stage of understanding where they will be able to understand the following paragraph written by Shougat Dasgupta in Tehelka.

“Bhagat is adept at this sort of corporate speak, bland pabulum that appears to be reasonable, but is buzzword piled upon truism piled upon platitude, a tower built on the soft, tremulous sands of cliché. A Bhagat column makes a house of cards seem as substantial as the pyramid at Giza.”

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 14,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/india/why-chetan-bhagat-sells-despite-the-mediocrity-tag-417177.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])