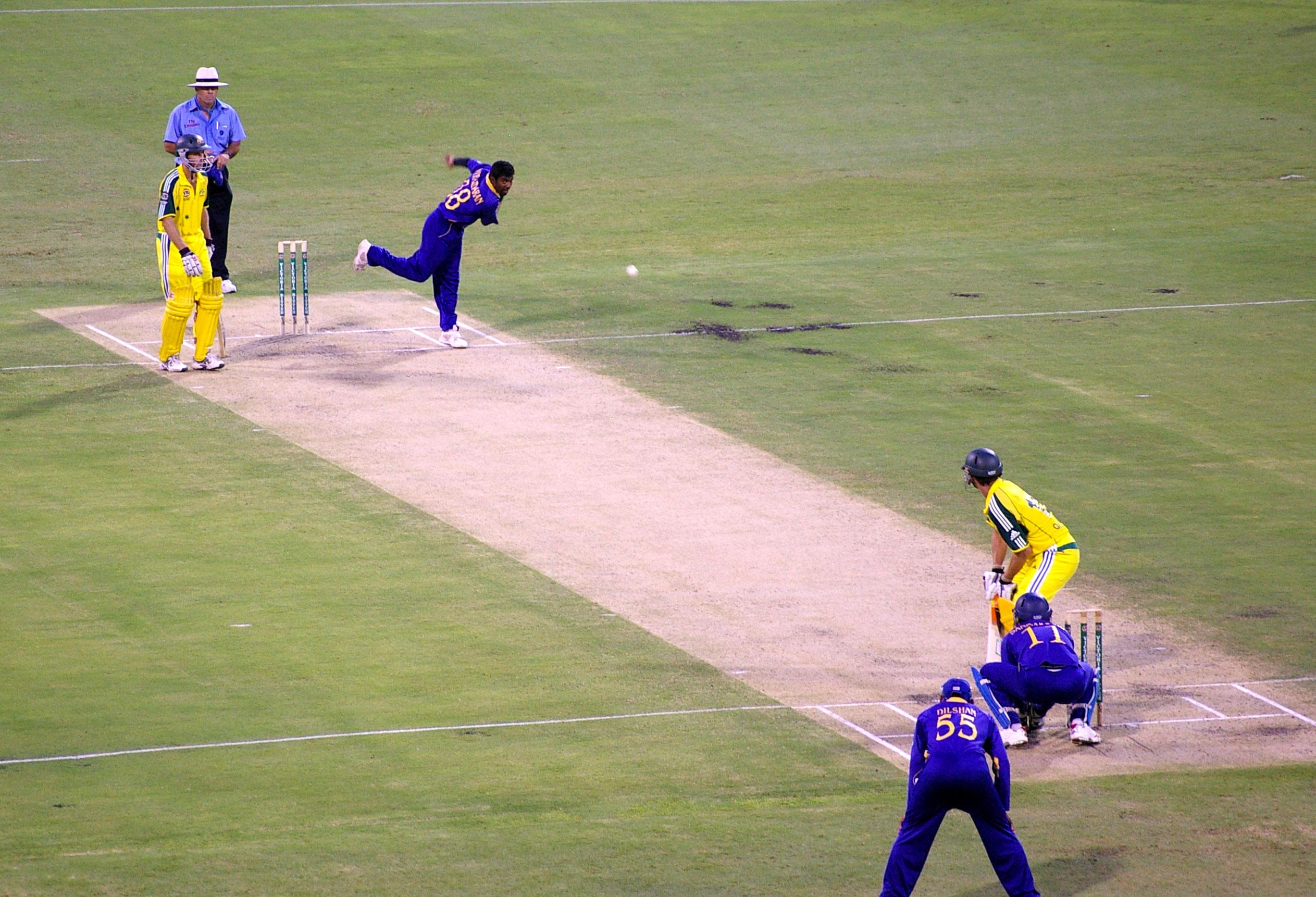

The Indian Premier League(IPL) is just about to come to an end. The Bangalore team did not do particularly well in this year’s edition and won only three out of their 14 games. They lost 10 games and one game was drawn because of rains.

The team was a finalist last year and lost to Hyderabad in the final. Given this, at the beginning of the 2017 season, nobody expected that the Bangalore team would come last among the 8 teams. Nevertheless, reasons are now being offered on why the Bangalore team did not do well this time around.

While analysing and offering reasons is fine, some of the cricket experts are now saying that they always knew that Bangalore wouldn’t do well this year. Multiple reasons have been offered. Here are a few that I have heard.

The captain Virat Kohli was injured and missed the first few games. KL Rahul missed the entire tournament because of an injury. Chris Gayle was not in his usual form. AB de Villiers was also injured and came in only after the first few games. One expert even said that the injury to batsman Sarfaraz Khan hit the team hard. And hence, the team was never able to build the momentum that is required to keep winning T20 games.

While all this sounds fine, none of these reasons were offered at the beginning of the tournament. At the beginning of the tournament none of the experts said that they don’t expect the Bangalore team to do well this year. But now once the Bangalore team has not done well, they are busy coming up with various reasons to explain the non-performance.

And along with that they are convinced about the fact that they had always believed that the Bangalore team would not do well this year. As David Hand writes in The Improbability Principle: “After the fact, it’s easy to put the pieces together, and show how they form a continuous chain leading to the outcome.” Or to put it simply, everything is obvious once you know the answer. Hence, Bangalore did not do well because Kohli was injured and could not play in the first few games. Bangalore did not do well in these games and in the process, they were never able to build the required momentum which is an essential part of a tournament of this kind.

This kind of storyline could not have been offered at the beginning of the tournament. As Hand writes: “Before the fact, however, there are many pieces and potential chains and it’s just not possible to know which events fit together. This isn’t because there are too many pieces, but simply because they can be put together in a vast number of possible ways, and there’s no reason to select any one of them.”

Hence, before this year’s IPL started one did not know that Chris Gayle, the master of the T20 game, would have the kind of disastrous year he did. It was always difficult to predict that the likes of de Villiers, Travis Head and Shane Watson, brilliant T20 players in their own right, wouldn’t have much of an impact on Bangalore’s overall performance. Even Kedhar Jadhav burdened with the responsibility to keep wickets, looked out of touch.

But all this and more can be now said with confidence, almost at the end of the tournament. As Hand writes: “Our innate tendency to retrospectively adjust a new recollection as new information becomes available, to identify the chain which led to the disaster and to say, after the fact, ‘Look, it was staring us in the face!’ is called hindisight bias.”

The point being that Bangalore lost because they did not score enough runs and they did not take enough wickets. Any analysis beyond this, is essentially hindsight bias.

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on May 17, 2017