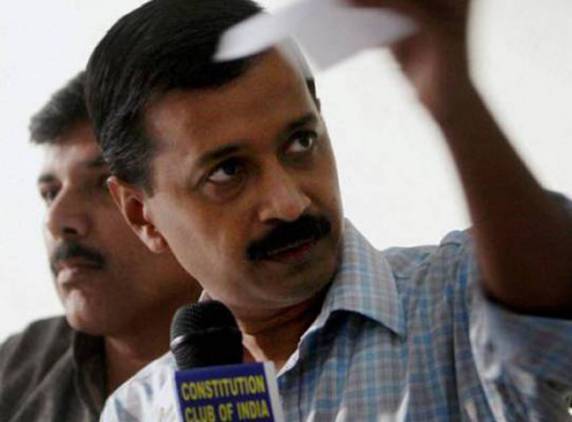

Last week saw David(read the Aam Aadmi Party(AAP)) beat Goliath(read the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP)) in the Delhi elections. AAP won 67 out of the seventy seats in the Delhi assembly, leaving only three seats for the BJP. This led to one WhatsApp forward which suggested that Delhi should now allow tripling(three people travelling on a bike) so that BJP legislators could ride to the Delhi assembly on a bike. Another forward suggested that the BJP legislators could drive to the assembly in a Tata Nano.

Jokes apart, in the aftermath of this electoral debacle many reasons have been offered on why and how the BJP lost Delhi. Reasons have also been offered on why and how the AAP won Delhi. Let’s sample a few here. The ghar wapasi campaign launched by the Sangh Parivar backfired in Delhi. The BJP ran a very negative and a highly vitriolic campaign against AAP and that didn’t quite work.

The AAP supporters on the other hand have been pointing out to the fact that the party ran a positive campaign and that went down well with Delhi residents. Further, the 49 days that Arvind Kejriwal was chief minister of Delhi, the levels of petty corruption in Delhi had come down dramatically. And this, we are told, is something that the people of Delhi haven’t forgotten.

Long story short—the number of reasons offered on AAP’s spectacular performance and BJP’s wipe out, is directly proportional to the number of political pundits analysing the issue. Nevertheless, most of these reasons have been offered with the benefit of hindsight. Most political pundits had no clue about BJP ending with up three seats and the Narendra Modi juggernaut losing steam. But now that it has happened, they need to find reasons and explanations for the same.

As Gary Smith writes in Standard Deviations—Flawed Assumptions, Tortured Data and Other Ways to Lie With Statistics: “Through countless generations of natural selection, we have become hardwired to look for patterns and to think of explanations for the patterns we find…We yearn to make an uncertain world more certain, to gain control over things we do not control, to predict the unpredictable.”

Also, some political pundits have now even said that they saw the whole thing coming and offered explanations of the same. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes in Fooled by Randomness: “Things are always obvious after the fact…It has to do with the way our mind handles historical information…Our mind will interpret most events not with the preceding ones in mind, but the following ones.” This tendency is referred to as hindsight bias in psychology.

Daniel Kahneman defines this in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow: “When an unpredicted event occurs, we immediately adjust our view of the world to accommodate that surprise…Once you adopt a new view of the world(or of any part of it), you immediately lose much of your ability to recall what you used to believe in before your mind changed.”

This leads to a situation where one feels that one has understood as well as predicted the past and given that one further feels that one can predict as well as control the future. As Jason Zweig writes in Your Money & Your Brain—How the New Science of Neuroeconomics Can Help Make You Rich: “Hindsight bias is another cruel trick that your inner con man plays on you. By making you believe that the past was more predictable than it really was, hindsight bias fools you into thinking that the future is more predictable than it ever can be.”

This is exploited in particular by financial pundits. As Kahneman writes: “Our tendency to construct and believe coherent narratives of the past makes it difficult for us to accept the limits of our forecasting ability. Everything makes sense in hindsight, a fact that financial pundits exploit every evening as they offer convincing accounts of the day’s events. And we cannot suppress the powerful intuition that what makes sense in hindsight today was predictable yesterday.” That of course is not the case.

Hindsight bias also is also at work when we invest. An excellent example, is of investors saying after a bubble has burst, that they knew all along it was a bubble. But the thing is that if a bubble is obvious to enough investors at the time it is in its initial stage, there would be no bubble in the first place.

Zweig has an excellent example in his book of the link between hindsight bias and investing. As he writes: “In the fall of 2001, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, you tell yourself, “Nothing will ever be the same again. The U.S. isn’t safe any more. Who knows what they’ll do next? Even if stocks are cheap, nobody will have the guts to invest.” Then the market goes on to gain 15% by the end of 2003, and what do you say? “I knew

stocks were cheap after September 11th!””

The moral of the story here is that you may have been able to explain the entire situation to yourself, but you have missed out on the rally.

Then there is the case of missing out on a bumper initial public offering. Zweig offers the case of Google which first sold its shares in August 2004. At that point of time, an investor wanting to invest in the stock, would have thought back about the bursting of the dotcom bubble and the money that he had lost back then.

Using this logic he would have decided not to invest in the stock. He would have then seen the price of the stock jump from the initial price of $85 to $460 by end 2006 and told himself: “I knew I should have bought Google!”

And this would lead to a change in the worldview of the investor and may well make him “more eager to take the plunge” the next time he has “a chance to get in on the ground floor of a risky high-tech start-up.” But as Zweig puts it: “Of course, “the next Google” may turn out to be the next Enron instead.”

Given these reasons it is very important for investors not to become victims of the hindsight bias while investing.

(The article originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com as a part of The Daily Reckoning on Feb 16, 2015)