There is a sucker born every minute. I was reminded of this earlier in the day today, when late in the afternoon, that time of the day when I snooze after having had my lunch, I got a random call. For some reason, truecaller didn’t pick up the name of the incoming caller, and I took the call.

The call was from a financial planner’s office and a female was talking at the other end. She said a new fund offer (the technical term for a new mutual fund scheme) from a mutual fund was being currently sold, and that I should invest in it. (Why in the world would I invest in a new scheme and not in something tried and tested, is a question that I didn’t bother to ask).

She started with the usual bull about the long-term returns on the mutual fund expected to be very good (Again, I didn’t bother to ask, if she knew the future, why is she making a living making calls. That would have been very mean).

I replied like I usually do when I am not interested, with a polite hmmm, which doesn’t mean anything.

And then she let it slip, very casually: “Sir, units are available for just Rs 10 per unit.” That caught my attention. It had been years since I had heard that.

The oldest mutual fund misseling trick, something I had made my career writing on during the days I used to write on personal finance, ten to fifteen years back.

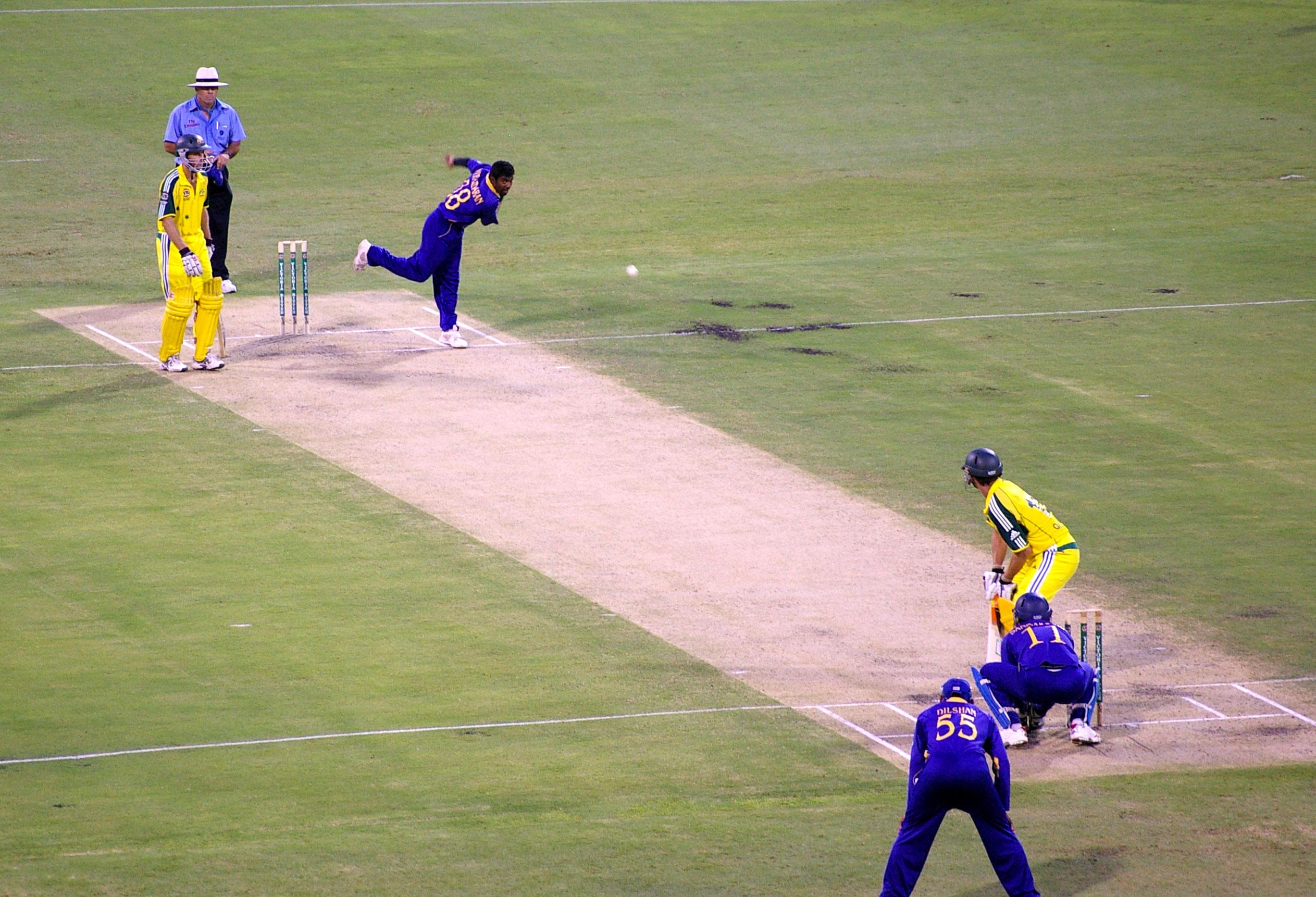

It took me back to 2004 to 2007, when stocks were rallying big time and new equity mutual fund schemes were launched dime a dozen. I was reminded of one scheme which had a theme of investing in stocks depending on where the head office or the registered office of the company was (some such thing). Those were the days my friend. Anything sold.

Hoardings on bus stands across Mumbai were plastered with the advertisements of new mutual fund schemes, with the Rs 10 price at which you could buy a single unit of the scheme, being prominently displayed. Even the mutual fund was trying to anchor the prospective investors to the price of Rs 10 per unit.

As Jason Zweig writes in Your Money and Your Brain in the context of anchoring:

“That’s why real estate agents will usually show you the most expensive house on the market first, so the others will seem cheap by comparison and why mutual fund companies nearly always launch new funds at $10.00 per share, enticing new investors with a “cheap” price at the beginning. In the financial world, anchoring is everywhere, and you can’t be fully on guard against it.”

The stupid me had assumed that all these misseling tricks would have been replaced by newer ones by now. But I guess with every bull run a new set of suckers are produced and India is a big country.

Anyway, I told the caller, madam no money. She then made some polite noises about this being a good opportunity and I should invest in it, and that was that.

For people who don’t know about this misselling trick this is how it works. When a new mutual fund scheme is launched, the price is set at Rs 10 per unit. Investors buy these units. If the mandate of the scheme is to invest in stocks, the mutual fund collects the money and invests it in stocks.

The price of a unit at the launch is set at Rs 10 per unit. This creates a perception of a cheap price in the mind of the investor. The older schemes, given that they have been around for a while, have higher prices.

Let’s say an older scheme which has been around for a while has a price of Rs 100. This higher value is because the scheme was launched many years back and the stocks that the scheme invested in over the years have gone up in value. In the process, the price of the scheme has also gone up.

Now let’s say you invest Rs 1 lakh in the scheme with a price of Rs 100. Assuming no expenses for the sake of simplicity, you will get 1,000 units (Rs 1 lakh divided by Rs 100) of the scheme. Now let’s say instead of investing in the old scheme, you end up investing in the new scheme at Rs 10 per unit.

You end up with 10,000 units (Rs 1 lakh divided by Rs 10) in the new scheme. 10,000 units is ten times 1,000 units. This creates the perception of a cheap price in the mind of the investor, thus misleading the investor into buying the new scheme and not the old scheme.

But does it really matter? Let’s say the new scheme invests in exactly the same set of stocks as the old one. The price of these stocks goes up 10%. Thus, the price of a single unit of the old scheme goes up to Rs 110 and that of a single unit of a new scheme to Rs 11. But the value of the overall investment in both the cases is Rs 1.1 lakh (Rs 1 lakh plus 10% return on Rs 1 lakh).

Let me explain this in even simpler way. Let’s say you have Rs 10,000 cash lying with you. You can have it in five notes of Rs 2,000, 20 notes of Rs 500, 50 notes of Rs 200, 100 notes of Rs 100, 200 notes of Rs 50, 500 notes and/or coins of Rs 20, 1,000 notes and/or coins of Rs 10, 2,000 coins of Rs 5, 5,000 coins of Rs 2, 10,000 coins of Re 1 or in different combinations of these notes and/or coins.

But at the end of the day, the total amount of money would still be Rs 10,000. It wouldn’t matter what denominations of notes and coins you have that money in. In the same way, the number of units you own in a mutual fund doesn’t really matter. What matters is how well the money you have invested in the mutual fund scheme, is invested further, and at what rate it grows (or falls for that matter).

Which is why, it makes little sense in investing in new schemes. But it makes absolute sense in sticking to old schemes which have had a good track record. Of course, for the mutual funds it makes sense to rely on these subtle misseling tricks because more the money invested with them, more the money they make.

Anyway, I didn’t think I would need to write this in 2021. But as the old French saying goes (and I don’t know how many times I have ended a piece with this), “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” The more things change, the more they remain the same.

Of course, whether you want to be a sucker or an informed investor, the choice is clearly yours. As the old Delhi Police ad went, marzi hai aapki aakhir sir hai aapka.

PS: An added bonus the legendary Baba Sehgal’s all time classic, mere paas hai mutual fund.