Ravi Venkatesan is the former Chairman of Microsoft India and Cummins India. He is currently a director on the boards of Infosys and AB Volvo. Most recently he has authored Win in India, Win Everywhere – Conquering the Chaos (Harvard Business Review Press, Rs 895). In the book he makes a case for multi-national companies (MNCs) not to ignore India, despite the country being a VUCCA market (i.e. operating in an environment characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, corruption and ambiguity). In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

The first thing I felt after reading your book was that given the current scenario in our country, its a tad too optimistic….

The reality of the Indian economy is very grim. But in spite of that companies need to find a way to break through. India is one of those extraordinarily fortunate countries which has to do nothing to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). People are dying to come here. We just have to stop scaring them away. Unfortunately we have done a pretty good job of scaring them away to the point where they are really losing interest.

Why have only a few MNCs succeeded in India?

Because only a handful of them have taken the country seriously. It takes three things to succeed in a market like India. Number one is the mindset. Companies need to realise that India is strategically important. It may not have their act together now, but a country of billion people cannot be ignored without consequences. So lets take a long term view. Lets be a leader. That is the mindset needed.

The second thing you need is to get the leadership right. You need a stable leadership team you can trust. You empower them overtime to take most of the decisions. But very few companies have succeeded in doing that. For most of them it is a fast moving sales outfit with no imagination.

The third thing you have to get right is that you have to realise you have to adapt to the country rather than wait for the country to catch up to your business model.

In India the business model may never catch up with you….

Yes. So if you are Apple and you say listen I am going to wait till the distribution system is more efficient and more Indians can afford the iPhone as is. Fine yaar.

Meanwhile the Indians will buy a Samsung...

Yeah. They will buy a little Samsung. A little HTC. A little Nokia. And you are going to be wiped out. When you look at it, this doesn’t sound to be much. But it is an extraordinary one in a hundred who actually gets these three elements right.

So the mindset is very important?

Yes. The global headquarters might say oh my God if they come up with something it will cannibalise my rich product. Imagine an iPhone that is half the price and almost everything that an iPhone is. That would not be good news. It would mean cheapening the brand and destroying the profitability of the company because the Americans will ask why can’t I have that phone as well. And so usually companies decide that do nothing is a good strategy.

Can you give us an example of a company which came to India, tried establishing its business model which did not work and then adapted it with success…

Microsoft came to India with its arrogance and established a certain presence. Then Bill Gates woke up and he realised, hey listen we have a $100 million business and 1000 people in a country of a billion people. What is going on? This was 2003. So they hired me in all their wisdom, even though I did not know anything about IT.

What was one of the main issues facing the company? Back then the piracy rate was 75%. Bill said this is okay. We will get them using it, one day we will collect. Steve Ballmer said, time has come to collect. “You are the country head, you collect,” he told me.

What did you do?

I went around enforcement, ye wo kiya, par kuch nahi hua (did this and that, but nothing happened). Then one minister, who shall remained unnamed, called me, and spoke to me in Tamil, and said “listen, you seem like a good guy, but maybe a little stupid. So let me give you some advise. Copyright in India means right to copy. So you change your business model because India is not going to change for you guys.” So we changed our business model in 2006-07. We changed our pricing. We came up with local language versions. Changed distribution and took the piracy rate down from 75% to 64% and saw dramatic growth.

You cut prices dramatically…

Office used to be $300. We came up with Office Home and Student which is $60. We came up with a version of Office for government schools which was $2. So if somebody said what is the price of Office in India? The answer was I don’t know. It’s free if you are an NGO. It’s two dollars if you are a school, and its $300 if you are Infosys. So that is adapting your business model for the reality of a country.

Any other examples?

JCB is a beautiful example. Everyone else came with an excavator. These guys came with a backhoe Bakchoes was 1960s technology, but India needed a backhoe. The country needed something low tech, very versatile and very inexpensive. They also localised to get the price point right. Also everybody optimises a machine for productivity i.e. how much mud can you dig in one hour. These guys optimised it for fuel efficiency i.e. how much mud can I dig per litre of diesel. Every point they made a different decision based on the market. How do you adapt your equipment so that it can run on adulterated diesel and abuse? You can’t find operators to run the machines. So lets start schools for backhoe operators across the countries.

The other companies did not do these things?

Everybody else was saying when the market comes up, then we will do it. These guys created the market and so they own it. Do you have a microwave oven from Samsung?

No…

It doesn’t say time setting. It says dal. It figures out the time and setting on its own.

That is a great innovation…

And it is so simple. And it will also in certain models say dal in Hindi. Is this rocket science or genius? No it is paying attention to your customer. That is all it is.

The interview originally appeared in Daily News and Analysis on July 27, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Daily News and Analysis

Subsidies = Inflation = Gold problem

The government has a certain theory on gold as per which buying gold is harmful for the Indian economy. Allow me to elaborate starting with something that P Chidambaram, the union finance minister, recently said “I…appeal to the people to moderate the demand for gold.”

India produces very little of the gold it consumes and hence imports almost all of it. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. When someone from India buys gold internationally, Indian rupees are sold and dollars are bought. These dollars are then used to buy gold.

So buying gold pushes up demand for dollars. This leads to the dollar appreciating or the rupee depreciating. A depreciating rupee makes India’s other imports, including our biggest import i.e. oil, more expensive.

This pushes up the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) as well as our fiscal deficit (the difference between what the government earns and what it spends).

The fiscal deficit goes up because as the rupee depreciates the oil marketing companies(OMCs) pay more for the oil that they buy internationally. This increase is not totally passed onto the Indian consumer. The government in turn compensates the OMCs for selling kerosene, cooking gas and diesel, at a loss. Hence, the expenditure of the government goes up and so does the fiscal deficit. A higher fiscal deficit means greater borrowing by the government, which crowds out private sector borrowing and pushes up interest rates. Higher interest rates in turn slow down the economy.

This is the government’s theory on gold and has been used to in the recent past to hike the import duty on gold to 6%. But what the theory doesn’t tells us is why do Indians buy gold in the first place? The most common answer is that Indians buy gold because we are fascinated by it. But that is really insulting our native wisdom.

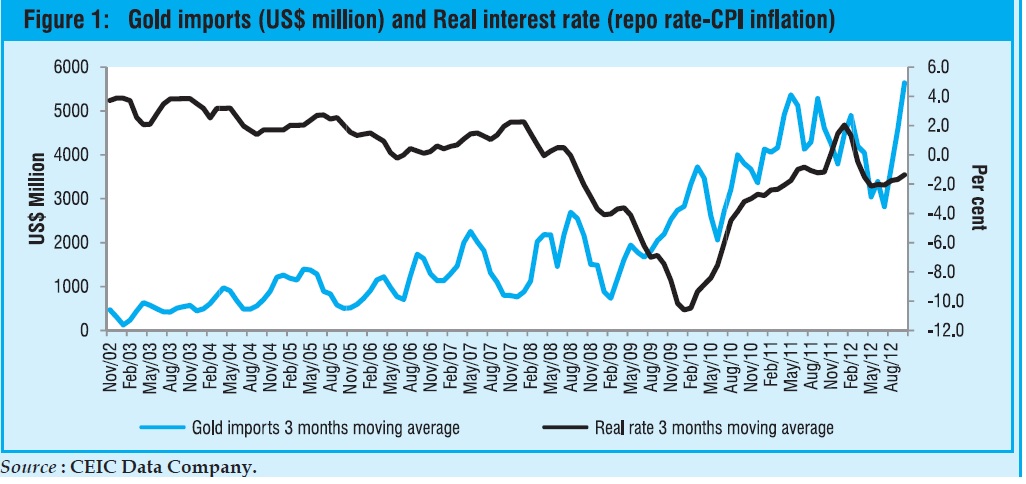

World over gold is bought as a hedge against inflation. This is something that the latest economic survey authored under aegis of Raghuram Rajan, the Chief Economic Advisor to the government, recognises. So when inflation is high, the real returns on fixed income investments like fixed deposits and banks is low. As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.”(as can be seen from the accompanying table at the start)

In simple English, people buy gold when inflation is high and the real return from fixed income investments is low. That has precisely what has happened in India over the last few years. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Survey points out.

High inflation in India has been the creation of all the subsidies that have been doled out by the UPA government. As the Economic Survey puts it “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.”

Inflation thus is a creation of all the subsidies being doled out, says the Economic Survey. And to stop Indians from buying gold, inflation needs to be controlled. “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance,” the Survey points out. So if Indians are buying gold despite its high price and imposition of import duty, they are not be blamed.

A shorter version of this piece appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on February 28, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Downgrade fuss's overdone. Who cares?

India’s fiscal deficit has reached worrying proportions. During the first six months of the year it had already crossed 65% of the year’s target of Rs 5,13,590 crore. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

The government’s effort to raise revenues has barely gone anywhere. During the half of the year only 40% of the targeted revenues had been raised. The recent 2G auction was a damp squib and the disinvestment process has barely started.

So what is the way out? “You know you always find some way out. Nobody quite believes the fiscal targets as yet. It is still all about hope and let’s see what happens in the next few months,” says Ruchir Sharma, the head of Emerging Market Equities and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “Only thing that which makes me sound a bit positive in terms of hope that at least they have recognised the problem. Till a year ago, even till April, there was no recognition of the problem. And that to me is at least a positive that we can look on.”

Given the slackening finances of the Indian government there has been a lot of talk about the rating agencies downgrading India, something, if media reports are to be believed, even the finance minister P Chidambaram is worried about.

But Sharma feels the threat is majorly overblown. “I just feel this fuss about that is really overdone to be honest with you because who cares! They (the rating agencies) are far behind, so whether we get downgraded or not, to me it just doesn’t matter and that doesn’t change anything for us,” says Sharma.

Explaining his logic Sharma says “Let me put it this way. If growth is less than 5% etc, that would be horrendous. But I think the reasons for the downgrade are already well telegraphed. If it happens it will be a formality. It will be a short term negative undoubtedly.”

The other big worry in India right now is inflation. “Commodity prices are generally down globally and that should help inflation. The problem is the same that unless we put an end to this populist surge in terms of spending you can’t get a meaningful decline in interest rates,” says Sharma.

“That really is at the core of the problem as far as inflation and interest rates are concerned. How do you put an end to that culture? That genie is out of the bottle. How do you put it back in?,” he asks.

The main problem that remains for inflation is just that there is too much government spending going on and too much of it is inefficient, feels Sharma. “This at a margin is a problem that is getting better,” he adds.

But the real test for the government would be whether they are able to put off the food subsidy kind of schemes. As Sharma puts it “To me the real signal will come if they back down on these populist schemes. Such as the whole food subsidy bill etc. The real fear that I have now is that we do all this now and this is only preparing for another populist scheme at the end of it, at the first sign when things are manageable or things are brought under some control. The fact that they can postpone such things or put them completely away will be a very positive sign. But until then I don’t know.”

The realisation that needs to come in is that government spending as a share of India’s gross domestic product is too high. “You can’t carry on this way. Not because it’s bad thing to do but you can’t keep writing cheques which the exchequer can’t cash. To me that is the bottomline. That spending now for a country of India’s per capita income level of $1500, government spending as a share of GDP is too high.”

Government scams have also been a major issue in the recent past. Sharma feels that this does impact India’s perception in the West. “For them it reinforces the fact about two issues that they have had with India. One is the fact that it is a tough place to do business in. And that shows up in all the metrics like the ease of doing business that World Bank and IMF put out, India ranks in the bottom quartile of most of these things. It also highlights that in India it is very difficult to do greenfield projects and set something up. You might as well be a partner with one of these guys who can get stuff done in India,” says Sharma. “But this is something that people have known and this just reinforces their perception,” he adds.

The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on December 3, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Do we want a society where everything is up for sale?

Michael J. Sandel is one of the foremost political philosophers of our times. He is the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government at Harvard University, where he has taught political philosophy since 1980. His book, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?, relates the big questions of political philosophy to the most vexing issues of our time. His new book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, argues that we have drifted from being a market economy to being a market society. In the book Sandel tries to answer what is the proper role of markets in a democratic society, and how can we protect the moral and civic goods that markets do not honour and money cannot buy. Sandel will be in India early next year speaking at the Jaipur Literature Festival. In this freewheeling interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Michael J. Sandel is one of the foremost political philosophers of our times. He is the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government at Harvard University, where he has taught political philosophy since 1980. His book, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?, relates the big questions of political philosophy to the most vexing issues of our time. His new book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, argues that we have drifted from being a market economy to being a market society. In the book Sandel tries to answer what is the proper role of markets in a democratic society, and how can we protect the moral and civic goods that markets do not honour and money cannot buy. Sandel will be in India early next year speaking at the Jaipur Literature Festival. In this freewheeling interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

One of the reasons you wrote What Money Can’t Buy was to reintroduce moral philosophy into conversations about market forces. Why was that necessary?

The last three decades have been a period of market triumphalism. The era started with the likes of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan proclaimed their conviction that markets not, government, held the key to prosperity and freedom. We have drifted from having a market economy to becoming a market society. And the difference is this. A market economy is a valuable and effective tool for organising productivity activity. And market economy has brought prosperity and affluence to countries around the world. A market society is different. A market society is a place where almost everything is up for sale. It’s a way of life in which uses markets to allocate health, education, public safety, national security, environmental protection, recreation, procreation, and other social goods. This was unheard of three decades back. And when this happens market values crowd out non market values worth caring about. So I think we need to step back and have a public debate about what should be the role of money in markets in our society. We need to ask where market mechanism suits the public good and where they don’t belong. There has been an expansion of market and market values, into spheres of life, where they don’t belong.

You just said that markets have colonised too much of society, spreading unchecked into healthcare, education and military matters with unforeseen moral consequences. Could you explain that in some detail?

Let me give you a couple of examples. In Iraq and Afghanistan there were more paid military private contractors on the ground than U.S. military troops. We never had a public debate whether we wanted to outsource war to private companies. But this is what happened.

Now take education many school districts in the United States are experimenting with the use of cash incentives to improve academic performance especially for students with disadvantaged backgrounds. So they are offered cash incentives for good grades, for high test scores and in one case they even offered young children two dollars for each book they read. Now the goal is of course a good one to improve academic performance. But the danger is that offering students money to learn may teach them the wrong lesson. It may teach students to regard reading books as a chore against making money rather than an activity which is intrinsically satisfying and worthwhile. That’s my worry.

Any other examples?

The number of private guards in Great Britain and the United States is twice the number of public police officers. Or consider the aggressive marketing of prescription drugs by pharmaceutical companies in rich countries. The funny thing is if you have ever seen the television commercials that accompany the evening news in the United States, you might come around to believing that the greatest health crisis in the world is not malaria or river blindness or sleeping sickness, but erectile dysfunction.

In your book you even talk about queues being up for sale nowadays. Can you share that with our readers?

In recent decades the ethic of the queue is being replaced by the ethic of money. The principle of first come first serve is being replaced by the ability to pay. This is happening in large places and small. If one goes to an amusement park it used to be the place everyone had to wait in the queue for the popular rides and attractions. Now most amusement parks have a fast track ticket that enables those who can afford to pay extra to go the head of the queue. The same is true for airports. Those who buy first-class or business-class tickets can use priority lanes that take them to the front of the line for screening. British Airways calls it Fast Track, which is a service that allows the high paying passengers of the airline jump the queue at passport and immigration control.

So what is the issue with that?

It may not be a morally serious problem at amusement parks or airports but increasingly the ethic of money is replacing the ethic of the queue throughout our social life. In Washington DC if one wants to attend a hearing of the United States Congress, often there are long queues. Sometimes people even wait in the queue overnight. Now lobbyists love to attend the Congressional hearings but they don’t have the time to stand in a queue. So they now hire line standing companies that in turn hire homeless people and others to wait in the queue so that the lobbyists can take his or her place in the queue just before the hearing begins and he can thus climb the queue. The same thing can be done by hiring the land standing companies to attend the US Supreme Court’s oral arguments. So what may seem innocent enough in amusement parks or concerts or waiting to buy the latest Apple iPod actually raises more serious questions when it is used to even in institutions which are representatives of governments.

But those who jump the queue really don’t see it like that?

They complain that queuing discriminates in favour of people who have the most free time. Yes that is right. But in the same way as markets discriminate in favour of people who have most money. Markets allocate goods on the ability and willingness to pay, queues allocate goods based on the ability and willingness to wait. And there is no reason to assume that the willingness to pay for a good is a better measure of its value to a person that the willingness to wait.

Why did Bruce Springsteen change only $95 per ticket for his shows in New Jersey in 2009, when he could have filled up the venue even by charging more? What does this tell us in the context of the broader argument you are trying to make?

Bruce Springsteen, in some cases, does not charge the full market price for tickets to his live concerts. He does that even though he could make more money by doing so. He limits the ticket price. And the reason he does this is partly to keep faith with his working class fans. And also because he recognises that his live performances are not purely market goods but part of the performance and part of what draws people to Bruce Springsteen and the spirit in which they gather together. A part of enjoying the Springsteen concert is the relationship between the performer and his fans, and the spirit in which they gather. This example is a metaphor for the kinds of choices that we should make, discuss and debate throughout our social lives and our civic lives.

Any other example that you could share with us?

When Pope Benedict XVI made his first visit to the United States, free tickets were distributed through local parishes. But the demand for tickets far exceeded the supply of seats. And soon a market was those tickets started to develop and one ticket sold online for more than $200. Church officials condemned this on the grounds that you cannot pay to celebrate a sacrament. Turning what are essentially sacred goods into what are essentially instruments of profits values them in the wrong way.

Do you think as a society we’re averse to talking about this connection, the moral implications of economics?

Yes, especially in recent decades we have not really debated the moral implications of economics. We do have some debate about distributive questions in relation to economics but what we have been more reluctant to do is another very important moral aspect of economics and that is the question that which goods and social practices should be governed by markets i.e. by the effect of buying and selling. Which goods should be commodified and be up for sale and which goods are damaged or degraded when we put a price tag on them. But most economists prefer not to deal with moral questions, at least not in their role as economists.

Can you explain through an example?

Most people would agree that we should not tag a market in children up for adoption because it would commodify and objectify children and possible erode the norm of unconditional parental love. Take another example most people would agree that we shouldn’t have an open market in votes in a democratic society even though from the standpoint of economic efficiency it’s hard to explain why not have a market in votes? Many people don’t use their votes. So as some free market economists advocate why shouldn’t people be free to sell their votes to other people who are willing to buy them? I think the reason we don’t allow this because it is considered that civic duties should not be regarded as private property but should be viewed instead as public responsibilities. Hence to outsource them is to demean them and value them in the wrong way. There are many areas of civic life where we have allowed money and markets to govern without having a serious public debate about the moral limits to market reasoning.

You talk about two objections to the concept of the market: the fairness objection and the corruption objection. What are these? Could you explain through an example?

Some free market economists argue that having a free market there should be a global free market in kidneys or other human organs for transplantation, and this would increase the supply. But there are two possible objections to this view. The fairness objection worries that a market in human organs would not involve truly voluntary exchanges but the poor would effectively coerced by the poverty and desperate need, to the affluent. That’s the fairness objection. The fairness objection worries about the inequality that may undermine the voluntary character of exchanges. The corruption objection is for reasons that go beyond inequality. It makes the argument that it’s a violation of human dignity to treat our body as a collection of spare parts to be bought and sold for money. The corruption objection worries about market values degrading or corrupting important human good. This is an example of what I mean by the distinction between the fairness argument and the corruption argument. Both arguments have to be a part of any public debate about the moral limit of economic reasoning.

A major point that comes out in your book is that monetary incentives sometimes undermine the intrinsic one and leads to worse performance. Why is that?

Some years ago in Switzerland they were trying to decide where to locate a nuclear waste site. No community wants one in its backyard. There was a small town that seemed to be the likely place for the nuclear place site. The residents of the town were asked to in a survey carried out by economists shortly before a referendum on the issue if they would vote to accept a nuclear waste site in their community, if the Swiss Parliament decided to build it there. Around 51% or a little over half of the respondents said they would accept it. The reason was that their sense of civic duty outweighed their concern about risks. The economists carrying out the survey then added a little twist to the entire exercise and asked a follow-up question.

And what was that?

They asked the residents of the community that suppose the parliament proposed building the nuclear waste facility in their community and at the same time offered to compensate them with an annual monetary payment, would they still favour it? You might sense that the number would have gone up to 80 or 90% but in fact the opposite happened. The support went down and not up. Adding the financial inducement to the offer reduced the rate of acceptance to 25% from the earlier 51%. The offer of money reduced the willingness of people to host the nuclear site in their community. Even when the economists upped the monetary incentive further the decision of the people did not change. The residents stood firm even when they were offered yearly cash payments of $8,700, which was more than the median monthly income of the area.

So what is the moral of the story?

This is an illustration in which a cash payment can crowd out a non market value. When the people were asked to make a sacrifice for a common good without paying them the majority said yes out of the sense of civic responsibility. But when they were asked changed their mind many of them said we didn’t want to be bribed. The offer of money changed the character of the offer. What had been a question of civic sacrifice for the common good now became a financial transaction, and many of those who were willing to accept the setting up of a nuclear site for the purpose of a common good, felt they were not willing to be bribed to subject themselves and their family to risk.

What is commercialisation effect?

Commercialisation effect is when buying and selling of a good previously governed by non market norms changes the character of the good. If you buy a flat screen television and gift it to me, then the flat screen television is worth the same either way. It would be the same good. But the same may not be true about health, education, national security, criminal justice, family relationships, civic life etc. In these areas introducing market mechanisms and cash incentives they change the character of the good and they drive out non market values worth caring about. The commercialisation effect happens when the offers of money the attitudes people have for the good they have exchanged. So going back to the education example where children are being paid to study and learn and go through the reading material, the commercilsation effect suggests that the performance of the children may improve in the short run but they change children’s attitudes towards reading and learning. In the long term they drive out the intrinsic love of learning.

Any other example?

Here I would like to give one another example which is perhaps the most classic example of this effect and that is prostitution. Most people would agree, even most free market economists would agree, that there is a difference between prostitution which is paid sex and non instrumental and non monetised sexual intimacy. And so perhaps the classic illustration of the commercialisation effect is prostitution. Another example is friendship. Till recently, you could bolster your online popularity by hiring some good looking “friends” for your Facebook page at 99 cents a month. This website was shut down after it emerged that photos of models that were being used were unauthorised. Even with this, people will agree that friendship is something money can’t buy, somehow, the money that buys the friendship dissolves it, and turns it into something else.

Can you summarise the entire argument for our readers?

The marketisation of everything means that people who are rich and people who are not rich have started to live increasingly separate lives. And that is not good for democracy, nor is it a satisfying way to live. Democracy does not require perfect equality, but it does require that citizens share in a common life. For this is how we learn to come to care about the common good. And so, in the end, the question of markets is really a question about how we want to live together. Do we want a society where everything is up for sale? Or are there certain moral and civic goods that markets do not honour and money cannot buy?

A shorter version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on November 5, 2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_do-we-want-a-society-where-everything-is-up-for-sale_1760214

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

‘Chance played a big role in the survival and success of Manchester United’

Paul Ormerod is the author of the bestselling The Death of Economics, Butterfly Economics and Why Most Things Fail. Most recently he has written Positive Linking – How Networks Can Revolutionise the World. “We are increasingly aware of the choices, decisions, behaviours and opinions of other people. Network effects – the fact that a person can and often does decide to change his or her behaviour simply on the basis of copying what others do – pervade the modern world,” writes Ormerod.In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul on why a small number of people can exercise a decisive influence on an eventual social or economic outcome, why copying others is a rational way to work in this world and why the football club Manchester United may have simply been lucky to get where they have.

What is positive linking?

It is basically the principle that ‘to him that hath, more shall be given’. The fact, for example, that a particular brand of smart phone has been selected by one of your friends makes it more likely that you yourself will make the same choice. It doesn’t mean that you will definitely make the same choice, but the more of your friends who have chosen the same phone, the more likely it is that you will.

You suggest that a relatively small number of people can exercise a decisive influence on an eventual social or economic outcome. Could you explain that through examples?

This is one way in which positive linking can work. It is by no means always the case that this the process by which people are influenced. Often, the way in which behaviour spreads is through ‘friends of friends’ networks, in which no single person has a strong influence. Ideological or religious movements are ones in which a small number of people often exercise decisive influence. Think, for example, of Hitler in Germany, or Osama bin Laden in our own times. But these ‘influentials’ can be found in other situations. For example, Gene Stanley and colleagues at Boston University found that the distribution of the number of sexual partners across a sample of individuals essentially had this structure. Most people had relatively few, and a small number had very many indeed. This latter group exercise a decisive influence on the spread of sexual diseases.

You write “we have inherently less control over situations in which network effects are important than we would like”. What is a network effect?

A network effect is a very important example of positive linking. Network effects, the fact that a person can and often does decide to change his or her preferences simply on the basis of what others do, pervade the modern world. This concept is just as crucial for companies and markets as it is for people. In September 2008 Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, precipitating a crisis which almost led to a total collapse of the world economy and a repeat of the Great Depression of the 1930s. It was precisely because Lehman was connected via a network to other banks that made the situation so serious. Lehman’s failure could easily have led to a cascade of bankruptcies across the world financial network, first in those institutions to which Lehman owed money, then spreading wider and wider from these across the entire network.

Why does network effect lead to less control?

A key point about network effects is that there is inherent uncertainty about how far any given effect will spread. We have some guidelines about what determines this. So, for example, if a person adopts a new product, and the people in his or her social circle are easily persuadable, it is likely that some of them will adopt it as well. But if it is hard to get them to try new things, they will not. In the former case, there is a chance that the product will get taken up on a large scale, in the latter it will not. But in any practical situation we simply cannot gather the incredibly detailed information which would be required in order to know for certain what the impact will be. We need to know the exact structure of the relevant network, who influences whom. And we need to know the degree of persuadeability of everyone in the network. We can get approximations to these, but we cannot know them for certain.

What is preferential attachment ?

Preferential attachment describes a particular way in which a person might copy the choices which others have made. Given a range of alternatives, he or she will choose between them with a probability equal to the proportion of times each alternative has been selected by others. So you are more likely to select the most popular choice, simply because it is the most popular.

Could you elaborate on that?

The basic idea is straightforward. Suppose there are just three choices available to you, whatever these may be, and you are wondering which one to select yourself. One has been already chosen 6,000 times, one 3,000 and the final one just 1,000 times, making a total of 10,000 altogether. If we assume for purposes of illustration that the only rule of behaviour you are using when making your choice is that of preferential attachment, the rule says the following. You may actually choose any one of the three alternatives. But you are twice as likely to select the most popular rather than the second most popular, and six times as likely to choose this as the least popular. You are paying no attention to the attributes, to the features of the three alternatives.

Any examples of this phenomenon?

Thetop three sites which are followed up on a Google search typically reflect exactly this pattern. The three of them get almost 100 per cent of the subsequent hits after the search, and the top one of them all gets 60 per cent of the total.

You say copying the best policy in this day and age. Why is that?

We are faced with a vast explosion of such information compared to the world of a century ago. We also have stupendously more products available to us from which to choose. Eric Beinhocker, formerly at McKinsey, considers the number of choices available to someone in New York alone: ‘The number of economic choices the average New Yorker has is staggering. The Wal-Mart near JFK Airport has over 100,000 different items in stock, there are over 200 television channels offered on cable TV, Barnes & Noble lists over 8 million titles, the local supermarket has 275 varieties of breakfast cereal, the typical department store offers 150 types of lipstick, and there are over 50,000 restaurants in New York City alone.’

That’s quite a lot…

He goes on to discuss stock-keeping units – SKUs – which are the level of brands, pack sizes and so on which retail firms themselves use in re-ordering and stocking their stores. So a particular brand of beer, say, might be available in a single tin, a single bottle, both in various sizes, or it might be offered in a pack of six or twelve. Each of these offers is an SKU. Beinhocker states, ‘The number of SKUs in the New Yorker’s economy is not precisely known, but using a variety of data sources, I very roughly estimate that it is on the order of tens of billions.’ Tens of billions!

So what does it tell us?

The customer has tens of billions of options to choose from. Compared to the world of 1900s the early twenty first century has seen a quantum leap in the number of choices available. And rather obviously the time taken to evaluate and choose rises with the number of choices. Many of the products available in the twenty-first century are highly sophisticated and are hard to evaluate even when information on their qualities is provide. Take the case of mobile tariffs that are available in the market. How many people can honestly say that they have any more than a rough idea of the maze of alternative tariffs which are available on these phones? The range and complexity of choice are so vast that the only way in which people can cope is by adopting behavioural rules which spectacularly reduce the scope of choices available to them. This is the key reason that ‘copying’ has become the rational way to behave, the rational way to make choices in the twenty first century. The word ‘copying’ is , I should stress being used as a shorthand description of the mode of behaviour in which your choice is influenced, altered, directly by the behaviour of others.

How much difference can the copying motive make to the outcome?

It can make a huge difference. Duncan Watts, a professor at Columbia, ran some experiments in 2006 and published the results in Science, probably the world’s top scientific journal. He set up an experiment where a student could listen to 48 songs, and download for free any which he or she wanted. A number of students carried out this experiment. The end result was that the most downloaded songs were about three times more popular then the least. The experiment was repeated, with just one difference. The student was told the number of previous downloads which each song had. The impact was huge. This time, the most popular songs were over 30 times more downloaded than the least popular. A few songs got lots of downloads, most got very few. In addition, the connection between quality and success was very weak. As Watts noted ‘The best songs rarely did poorly, and the worst rarely did well, but any other result was possible.’

You talk about economist Brian Arthur’s urn experiment. Could you tell our readers about it?? What is the practical significance of this experiment?

This seemingly abstract piece of work has great practical significance. It is another way of illustrating why the Watts’ experiments have the outcomes which they do. Arthur’s initial work was on a highly abstract concept in non-linear probability theory, something called Polya urns. Imagine we have a very large urn containing an equal number of red and black balls. (The colours are immaterial.) A ball is chosen at random, and is replaced into the urn along with another ball of the same colour. The same process is repeatedly endlessly. Within this enormous urn, can we say anything about the eventual proportions of red and black balls which will emerge? They start off with a 50/50 split. Can we say how this split will evolve?

Can we?

Indeed we can. Arthur and his colleagues showed that as the process of choice and replacement unfolds, eventually the proportion of the two different colours will always – always – approach a split of 100/0. It will never quite get there, because at the start there are balls of each colour, but the urn will get closer and closer to containing balls all the same colour. The trouble is, we simply cannot say in advance whether this will be red or black. Arthur’s equations also show that the winner emerges at a very early stage of the whole process. Once one of the balls, by the random process of selection and replacement, gets ahead, it is very difficult to reverse.

So what is the practical implication of this?

Suppose a new technology emerges. No one really knows how to evaluate the various products associated with it. The principle of copying seems entirely rational. Someone makes a choice. In the abstract model, this is the extraction at random of a ball from the urn. The fact that brand A has been chosen rather than brand B tilts ever so slightly the possibility that the next choice will also be A rather than B – this is the replacement rule in Arthur’s model. And so the process unfolds. In practice, of course, as one of the brands gains a lead over its rival, factors other than consumer copying will come into play and reinforce its dominance. There will be positive feedback, positive linking, so that success breeds further success. The more successful brand may be able to advertise more, for instance. Retailers will give more shelf space to it, and may even, in the splendid language of retailers, delist its rival, so that it becomes harder and harder to obtain. Technologies and offers which piggyback on the brands – think of apps and iPhones here – become increasingly designed to be compatible with the number-one brand.

You write “the most popular , the most successful, the biggest, does not stay there forever”.

Success is self-reinforcing, but it does not last forever. Indeed, even as I write these words, the West’s press is full of speculation that Google may be about to go into decline. The most popular video on YouTube today is rarely the most popular tomorrow. The song which is at number 1 this week does not usually stay very long in this position. Over the entire period from 1952 to 2006, no fewer than 29,056 songs appeared in the Top 100 chart in the UK. Of these, 5,141 were in the chart for just a single week. Almost exactly a half stayed in for less than a month, so four weeks was the typical life span, as it were, of a song in the Top 100. In contrast, fifty-nine remained popular for more than six months. The typical life span at number 1 was just two weeks.

Any other example?

At the other extreme is the ranking of the world’s largest cities. Mike Batty, a distinguished spatial geographer at University College London, published an analysis of this in Nature in 2005. He begins his work with the largest US cities from 1790 to 2000. Over the 210-year period, 266 cities were at some stage in the top hundred. From 1840, when the number of cities first reached one hundred, only twenty-one remain in the top hundred of 2000. On average, it takes 105 years for 50 per cent of cities to appear or disappear from the top hundred, whilst the average change in rank order for a typical city in each ten-year period is seven ranks.

How important is the element of chance and randomness in any successful enterprise or outcome?

In a world where network effects, where positive linking exists, chance and randomness are important. A lucky early break sets up positive feedback. Once you or your product have been selected, it makes it more likely that you will be chosen again in future. It is easy to see now, for example, why Manchester United are so successful. They possess global brand recognition and can attract massive sponsorship. But this was not always the case. Chance played a big role in their very survival, and in their subsequent success.

How was that?

Manchester United started life as essentially the works team of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway company, based in – and called – Newton Heath, then as now a poor district in the eastern part of the city. Just over 100 years ago, Newton Heath were served with a winding-up order. A consortium of local businessmen paid what in today’s money is around £750,000 to rescue the club, and changed its name to Manchester United. Despite some fleeting success, the club languished. In 1931 they were effectively bankrupt again and were rescued even more cheaply than before: for some £400,000 in today’s money. Yet in 2011, the value of Manchester United is of the order of £1 billion!

And chance had a role to play in it?

Chance elements also played a role in United’s subsequent success. Just before the end of the Second World War, the club offered the position of manager to Matt Busby, a man who built not one, not two, but three extremely successful teams during the course of his career. But Busby’s appointment itself was to a considerable degree one of chance. Thirty miles to the west of Manchester lies its great rival, the city of Liverpool. The antipathy between Manchester United and Liverpool FC, the second most successful English team ever, is intense. No player has been transferred directly between the two since 1964. Yet Busby almost joined Liverpool, who had been courting him for some time. The clincher appears to have been that Busby was friendly with a member of the United board through their membership of the Manchester Catholic Sportsman’s Club.

The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on October 29,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_chance-played-a-big-role-in-the-success-of-manchester-united_1757253

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])