In a few weeks, it will be the seventh anniversary of the start of the current financial crisis. The fourth largest investment bank on Wall Street, Lehman Brothers, filed for bankruptcy on September 15, 2008. A day later, AIG, the largest insurance company in the world, was nationalized by the United States government.

A week earlier two governments sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had also been nationalized by the United States government. In the months to come many financial institutions across the United States and Europe were saved and resurrected by governments all across the developed world. Some of them were nationalized as well.

Economic growth crashed in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Central banks and governments reacted to this by unleashing a huge easy money programme, where a humongous amount of money was printed(or rather created digitally) in order to drive down interest rates, in the hope that people would borrow and spend, companies would borrow and spend, and economic growth would return again.

And how are we placed seven years later? It would be safe to say that despite all that governments and central banks have done in the last seven years, the world hasn’t returned to its pre-crisis level of economic growth.

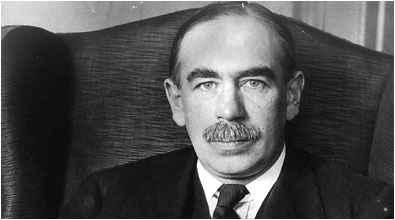

In fact, if we go by what the greatest economist of the twentieth century, John Maynard Keynes, wrote in his tour de force, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, a large part of the developed world is currently going through a “depression”.

Keynes, defined a depression as “a chronic condition of sub-normal activity for a considerable period without any marked tendency towards recovery or towards complete collapse.”

This is something that the economists tend to ignore. As James Rickards writes in The Big Drop—How to Grow Your Wealth During the Coming Collapse: “Mainstream economists and TV talking heads never refer to a depression. Economists don’t like the word depression because it does not have an exact mathematical definition. For economists, anything that cannot be quantified does not exist.”

Hence, if we go as per what Keynes said, depression is a scenario where economic growth is below the long-term trend growth. And that is precisely how large parts of the global world have evolved in the aftermath of the financial crisis. As Rickards writes: “The long-term growth trend for U.S. GDP is about 3%.

Higher growth is possible for short periods of time. It could be caused by new technology that improves worker productivity. Or, it could be due to new entrants into the workforce…Growth in the United States from 2007 through 2013 averaged 1% per year. Growth in the first half of 2014 was worse, averaging just 0.95%.”

The current year hasn’t been any better either. The economic growth between January and March 2015 stood at 0.6%. Between April and June 2015, it was a little better at 2.3%. As Rickards puts it: “That is the meaning of depression. It is not negative growth, but it is below-trend growth. The past seven-years of 1% growth when the historical growth is 3% is a depression as Keynes defined it.”

The United States economy accounts for nearly one-fourth of the global economy and if it grows slowly that has an impact on many other economies as well.

China, another big economy, has also been growing below its long term growth rate. Between 2003 and 2007, the Chinese economy grew by greater than 10% in each of the years. It slowed down in 2008 and 2009 as the financial crisis hit, and grew by only 9.6% and 9.2% respectively. In 2010, the economic growth crossed 10% again with the economy growing by 10.6%. This was after the Chinese government forced the banks to unleash a huge lending programme.

Nevertheless, growth fell below 10% again and since then the Chinese economy has been growing at below 10%. In fact, in the recent past, the economy has grown at only 7%, which is very low compared to its rapid rate of growths in the past.

Interestingly, people who observe China closely, are sceptical of even this 7% rate of economic growth. As Ruchir Sharma, Head of Global Macro and Emerging Markets at Morgan Stanley wrote in a recent column for the Wall Street Journal: “Chinese policy makers seem unwilling to accept that downturns are perfectly normal even for economic superpowers…But Beijing has little tolerance for business cycles and is now reviving efforts to stimulate sectors that it had otherwise wanted to see fade in importance, from property to infrastructure to exports….While China reported that its GDP grew exactly in line with its growth target of 7% in the first and second quarters this year, all other independent data, from electricity production to car sales, indicate the economy is growing closer to 5%.”

The moral of the story being that China is growing much slower than it was in the past. What this means is that countries like Brazil and Australia, which are close trading partners of China, will also feel the heat. Over and above this, much of Europe continues to remain in a mess. As Rickards puts it: “Keynes did not refer to declining GDP; he talked about “sub-normal” activity. In other words, it is entirely possible to have growth in a depression. The problem is that the growth is below trend. It is weak growth that does not do the job of providing enough jobs or staying ahead of national debt.”

In fact, much of the economic growth that has been achieved through large parts of the developed world has been on the basis of more lending carried out at very low interest rates. Data from the latest annual report of the Bank of International Settlements based out of Basel in Switzerland, suggests, that the total global debt has touched around 260% of the global gross domestic product (GDP). In 2008, it was around 230% of the global GDP.

As the BIS annual report for the financial year ending March 31, 2015 points out: “very low interest rates that have prevailed for so long may not be “equilibrium” ones, which would be conducive to sustainable and balanced global expansion. Rather than just reflecting the current weakness, low rates may in part have contributed to it by fuelling costly financial booms and busts. The result is too much debt, too little growth and excessively low interest rates.”

The tragedy is that there seems to have been no change in the thought process of those who are in decision making positions.

The column originally appeared on Firstpost on Aug 20, 2015

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)