When in trouble, politicians and countries go back to the British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes in his magnum opus The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money suggested that the way out of a low-growth or recessionary economic environment was for someone to spend more. In such a situation, citizens and businesses were not willing to spend more, given the state of the economy. So, the only way out of this situation was for the government to spend more on public works and other programmes. The Indian government has decided to do just that. On October 24, 2017, the finance minister Arun Jaitley, announced a Rs 6.92 trillion ($107 billion assuming one dollar equals Rs 64.7) road building programme for 83,677 km of roads, over the next five years. Out of this, the Bharatmala Pariyojana is to be implemented with Rs 5.35 trillion being spent on it for building 34,800 kilometre of roads. Economist Mihir Swarup Sharma writes in a column on NDTV: “Bharat Mala” is basically a reworked and updated form of the National Highways Development Programme that is almost two decades old.” The programme has been in the works for a while now. In fact, in an answer to a question raised in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of Indian Parliament, the government had said: “The Public Investment Board has cleared the proposal for BHARATMALA Pariyojana Phase-I in its meeting held on 16 June 2017.” In fact, there is nothing new about this. The Narendra Modi government, in the past, has shown a tendency to portray old schemes as new ones. Let’s leave that aside and concentrate on how this programme will be implemented. The government said that substantial delegation of powers has been provided to the National Highways Authority of India and other authorities and government departments. Over and above the Bharatmala Pariyojana, roads of length 48,877 km will be built under other current with an outlay of Rs .57 lakhs crores. This road building should help a significant portion of the one million youth entering the Indian workforce every month, find jobs. A large portion of this workforce is unskilled and semi-skilled and road building projects will help cater to this completive advantage of access to cheap labour, that India has. Just the Bharatmala Pariyojana is expected to create 14.2 crores mandays of jobs, according to the government. The government plans to raise finance for these road projects through a variety of measures. For the Bharatmala Pariyojana, Rs 2.09 trillion will be raised as debt from the financial market. Rs 1.06 trillion will be mobilised as private investments through the public private partnership. The remaining Rs 2.2 trillion will be provided out of accruals to the central road fund, toll collections of National Highways Authority, etc. For the other road projects Rs 0.97 trillion will come from the central road fund and Rs 0.59 million will come from the annual budget expenditures of the government in the years to come. Hence, on paper this sounds like a fool proof idea. The government will build roads. It will employ many people in the process and pay them. This income when spent will spur the businesses as well as the economy and India will grow at a fast-economic growth rate. QED. Only, if things were as simple as that. The government plans to build a total of 83,677 km of roads over five years. This implies building 16,735.4 km of roads on an average in each of the five years. Is that possible? Let’s look at the record for the last three years. In 2014-2015, the government built 4,410 km of roads in total. In 2015-2016, this jumped to 6,061 km in total. In 2016-2017 (up to December 2016), the government had built 4,699 km of roads. This data is from the annual report of the ministry of road transport and highways. A report in The Hindustan Times suggests that in 2016-2017, the government built 8,200 km of roads. If the government has to achieve the road building target that it has set for itself over the next five years, it has to more than double the speed at which built roads in the last financial year. And then maintain it for five years. This, seems like a tall order. Over and above this, acquiring land to build roads will not be an easy task. Nitin Gadkari, the minister of Road Transport and Highways told the Press Trust of India in an interview that even though land acquisition is “tough and complicated“, “it is not a problem for the ministry as farmers and others were making a beeline to offer their land for the highway projects after enhanced compensation.” But this is not going to anywhere as easy as the minister made it sound. Take the case of the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor which was announced almost a decade back. While work has started on it, most of the corridor is still plagued by land acquisition issues. To conclude, building roads to drive economic growth is a very old idea. In fact, it was put in action even before Keynes wrote about it in an indirect sort of way in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. While Keynes was expounding on his theory, it was already being practiced by Adolf Hitler, who had deployed 100,000 workers for the construction of the Autobahn, a nationally coordinated motorway system in Germany which was supposed to have no speed limits. Hitler first came to power in 1933. By 1936, the German economy was chugging along nicely, having recovered from a devastating slump and unemployment. Italy and Japan had also followed a similar strategy. How well will things work out in the Indian context? It will all depend on how well the government is able to execute the building of roads. The good bit is that Nitin Gadkari, one of the better performing ministers in the Modi government, is in charge. The bad part is that good execution is not something India is known for. The column originally appeared on BBC.com on October 28, 2017. |

John Maynard Keynes

Fiscal stimulus is already on, why doesn’t the govt try lowering taxes?

Media reports suggest that the central government is planning a fiscal stimulus. In simple English, what it basically means is that it is planning to spend more than what it had budgeted for, during this financial year.

Fiscal stimulus is an idea that politicians have latched on to for nearly eight decades since the British economist John Maynard Keynes published his tour de force The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936. What Keynes suggested in this book was that in a tight economic situation, cutting taxes, so that people would have more to spend, was one way out to revive economic growth.

But the best way was for the government to spend more money, and become the “spender of the last resort”. Also, it did not matter if the government ended up running a fiscal deficit in doing so. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. When Keynes wrote this book, governments budgets used to be balanced (i.e. expenditure was more or less equal to revenue).

It wasn’t fashionable for governments to run a fiscal deficit back then, as it is now. Given this Keynes suggested that in a tight economic situation (the world was going through what we now call the Great Depression) it made sense for the government to spend its way out of trouble. And if that meant running a fiscal deficit, so be it.

Since then, it has been time honoured tradition for politicians and a section of economists to talk about the government spending more, in times of economic trouble. The idea being that with the private consumption slowing down, if the government spends more, incomes will go up, and this will help in reviving private consumption expenditure, which in turn will push up economic growth.

QED.

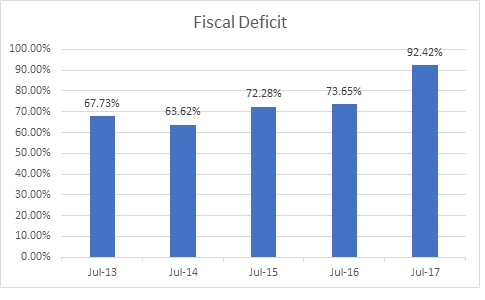

In fact, the government has already started providing a fiscal stimulus to the economy, during the first few months of this financial year. Take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Source: www.cga.nic.in and www.indiabudget.nic.in

What does Figure 1 tell us? It tells that between April and July 2017 of the current financial year, the government has already touched 92.4 per cent of the fiscal deficit target that it had set at the beginning of the year. As is obvious from Figure 1, this is way beyond what usually happens.

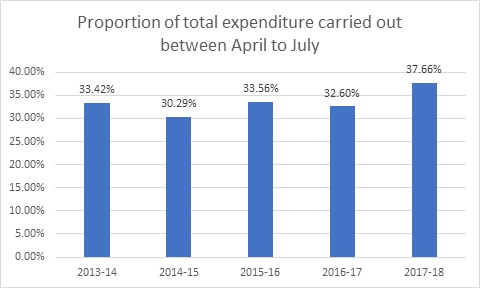

Now take a look at Figure 2. It plots the proportion of government expenditure carried out during the period April to July (the first four months of the financial year) against the total expenditure achieved/planned for the financial year.

Figure 2:

Source: www.cga.nic.in and www.indiabudget.nic.in

What does Figure 2 tell us? It tells us that during a normal year, the government spends around one-third of the total expenditure during the first four months of the year. And this is a logical thing to do, given that four months constitute one-third of a year.

This time around, the government expenditure during the first four months of the year is at 37.7 per cent of the total expenditure that the government plans to incur during the year.

What Figure 1 and Figure 2 tells us is that the fiscal stimulus is already on. If the government continues to spend at the same rate as it is currently, it will end up spending 13 per cent more than it had planned at the beginning of the financial year. This will push up the budgeted fiscal deficit by around 51 per cent (assuming government revenues remain the same).

This will push up the fiscal deficit to 4.9 per cent of the gross domestic product(GDP) against the set target of 3.2 per cent of the GDP. Now what the government needs to decide is whether it should continue spending money at the rate that it currently is.

Also, what this means is that people who are now asking for the government to unleash a fiscal stimulus, probably do not know, that a stimulus is already on.

In fact, the government spending more than the usual, helped the GDP grow by 5.7 per cent during the period April to June 2017. In fact, if we leave out the government expenditure from the GDP, the non-government part, which constitutes close to 90 per cent of the GDP, grew by just 4.3 per cent. Hence, the impact of the fiscal stimulus is clearly there to see.

The trouble is that most fiscal stimuli flatter to deceive. It does help in pushing up economic growth initially, but ends up creating more problems, which the economy has to tackle in the years to come.

India’s last experience with a fiscal stimulus was disastrous. It was unleashed in 2008-2009. It propped up economic growth for a couple of years. But it also led to high inflation and high interest rates. It also led to banks going easy on lending and in the process ended up creating a massive amount of bad loans, which the system is still trying to come out from.

Also, it is worth remembering that the state governments run fiscal deficits as well. During 2016-2017, the combined fiscal deficit of the central government as well as the state governments had stood at 6.5 per cent of the GDP, down from 7.5 per cent, in 2015-2016. During this financial year, many state governments are expected to run higher fiscal deficits because they have waived off farmer loans. With the central government also spending more, the combined fiscal deficit will cross the 7 per cent level and that is not a good thing.

People in decision making should remember these points raised above. The trouble is politicians like to look up to the next election. And the fiscal stimulus that has been unleashed now is likely to keep perking up economic growth over the next year or two and this will help the incumbent government in the next elections. Having said that, as I mentioned earlier, it creates other problems in the time to come.

Also, it needs to be clarified here, that Keynes wasn’t an advocate of a government running high budget deficits all the time. Keynes believed that, on an average, the government budget should be balanced. This meant that during years of prosperity, governments should run budget surpluses. But when the environment is recessionary, governments should spend more than what they earn, even running budget deficits.

But over the decades, politicians have only taken one part of Keynes’ argument and run with it. The idea of running deficits during bad times became permanently etched in their minds. However, they forgot that Keynes had also wanted them to run surpluses during good times.

To conclude, other than the government spending more, Keynes also talked about lowering taxes. Why doesn’t the government try and lower the GST rates to start with?

The column originally appeared on Firstpost on September 23, 2017.

When the Bank Has a Problem

In last week’s column, I wrote about the Orwellian Economics of Indian banking. The basic premise of the column came from something that George Orwell wrote in his book Animal Farm: “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.”

This is clearly being seen in Indian banking, in the way the banks treat loan defaulters. The small borrowers including small businesses, feel the full force of the bank’s system, in case they end up defaulting on the loan. Banks make all the effort to sell the collateral offered against the loan in order to recover the loan. In comparison, big corporates who default on the big loans, are treated with kid gloves.

A few readers emailed and wanted me to write a little more on this issue. So, here we go.

John Kenneth Galbraith writing in The Culture of Contentment makes an excellent point about the structure of the banking system. As he writes: “The man or woman who borrows $10,000 or $50,00 is seen as a person of average intelligence to be dealt with accordingly. The one who borrows a million or a hundred million is endowed with a presumption of financial genius that provides considerable protection from any unduly vigorous scrutiny.”

And how does this impact the way the banks lend money to prospective borrowers? As Galbraith writes: “This individual deals with the very senior officers of the bank of financial institution; the prestige of high bureaucratic position means that any lesser officer will be reluctant, perhaps fearing personal career damage, to challenge the ultimate decision. In plausible consequence, the worst errors in banking are regularly made in the largest amount by the highest officials.”

This is the self-destructive nature of the system. What this essentially means that the managers running banks are in awe of the promoters and managers of large corporates, who come to them to borrow money.

In the Indian context, what also does not help is the fact that public sector banking makes up for close to three-fourths of the banking system. A major part of the public-sector banks are ultimately owned by the central government. In this scenario, politicians end up influencing who the banks lend money to.

This at times includes companies and promoters whom the politicians are close to. The lending has nothing to do with the investment potential of a project for which money is being borrowed. This is a sort of a quid pro quo for the corporates financing the electoral costs of politicians and political parties.

In fact, sometimes the corporate promoter taking the loan brings in very little of his own money into the project. As former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan said in a November 2014 speech: “The reason so many projects are in trouble today is because they were structured up front with too little equity, sometimes borrowed by the promoter from elsewhere. And some promoters find ways to take out the equity as soon as the project gets going, so there really is no cushion when bad times hit.”

What this means in simple English is that lenders with political connections invest very little of their own money into the project they are majorly financing through the bank debt. This is something that the banks should catch on to during the time they carry out the due diligence of the project. But they clearly don’t due to the reasons offered above and that is why the Indian banks are currently in the mess that they are.

So, what is the way out of it? The long-term solution lies in the fact that politicians stop interfering with the lending process of public sector banks. And that can only happen if most even if not all these banks are privatised.

Until then, it is worth remembering what John Maynard Keynes said about banks: “If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe your bank a million pounds, it has.”

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on April 7, 2017

An Open Letter from an Indian Crony Capitalist

(This is a spoof)

Dear Indian Citizen,

Kem cho?

Kaamon Achish? Maja ma?

Hope all is well with you.

I am very happy these days. You know with that Rajan guy deciding to go back to Chicago. Good he is going back there.

I to wanted to open a champagne bottle to celebrate. But these children of mine always want this red wine shine.

And I to am still wondering, why would anyone in their right mind, comeback to India from the United States? Okay, maybe Chicago is very cold. My deekro tells me, they call it the windy city. It’s very cold up there it seems.

But then why stay on the East Coast? He could easily move to the West Coast. California. This Rajan guy. Very sunny, I am told. Just like Mumbai it is.

You know, when he was appointed as the RBI Governor, I got my kudi to buy all his books from this Amazon. Or was it Flipkart? I don’t remember. Been a long time since I went to the Strand Book Stall, you see.

So, this Rajan guy has written just two books, it seems. What men, been in the United States for nearly three decades and written just two books? Look at our very own Chetan. He has written so many more books than Rajan while holding a proper banking job at the same time, for a very long time.

And Rajan could write only two, with a teaching job?

So, one book of his is called, Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists. I started the book with great interest, after all I am also capitalist. But all the economic theory-weory got to me finally. And he just kept talking about Mexico. Our Chetan is so much better. North-South love story he wrote. What fun it was.

Didn’t Rajan also marry a North Indian? Why didn’t he write about that then and call it I too Had a Love Story? There is enough trouble in life anyway. Why write about such heavy stuff? And that is why I like watching this Tarak Mehta ka Oolta Chashma.

Oh talking of Mexico. Have you seen this latest Hindi film called Udta Punjab? In that, they compare Mexico to Punjab. Guess the director must have got the idea after reading Rajan’s book.

Anyway. I am meandering and meandering. Let me get to the point. In this Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists book Rajan writes: “Throughout its history, the free market system has been held back, not so much by its own economic deficiencies as Marxists would have it, but because of its reliance on political goodwill for its infrastructure. The threat primarily comes from…incumbents, those who already have an established position in the marketplace…The identity of the most dangerous incumbents depends on the country and the time period, but the part has been played at various times by the landed aristocracy, the owners and managers of large corporations, their financiers, and organised labour.”

First time I read this, I didn’t understand only what Rajan was saying. I read this paragraph over and over again and got worried. Then my son-in-law told me, Rajan is only economist. Economists talk only theory. They don’t do it in practical.

But I had this feeling that this guy meant business. He will practice his theory and try and clean up India’s banking system, I had a feeling. Why? I don’t know. I think Kejriwal came in my dream and told me this. And I was right about it.

You see, I had taken this huge loan from a public sector bank in 2008. Those were good days. Everything was looking good.

Indian economy was growing at a fast pace. And like any good capitalist I assumed that the economy will continue to do well and interest rates will continue to remain low.

But all that changed. Over the last four years I have been having difficulty in repaying the loan. No money only.

You see my problem. I have so much loan to repay. Rs 50,000 crore. On that I am paying interest of 12% i.e. Rs 6,000 crore a year. I am having difficulty in repaying interest. How will I ever repay the principal?

And interest is so high. If it was 8%, I would be paying only Rs 4,000 crore a year. Now I am paying Rs 6,000 crore. Rs 2,000 crore more. “Profit main ghato ho gayo!”

Shouldn’t the government help me also? Shouldn’t the interest rates come down? But this Rajan guy did not want to help me only. Kept interest rates high. On top of that he encouraged banks to come after our assets. And that too public sector banks? Imagine!

You know, this is not the first time I have over-borrowed. I did that in the late 1990s also. But somehow I managed to come out unscathed…he he…The taxpayers had to pick up the tab.

And that is only fair no. There are so many taxpayers and so few capitalists who have over-borrowed. No individual taxpayer will feel the pain of having bailed out the capitalists.

But this Rajan guy said no. He insisted on capitalists like me repaying. Selling our assets and repaying.

Imagine? In India? What is the world coming to?

So good only he is not taking a second-term. Going back to the United States.

And it’s time to celebrate. “Kuch murga shurga khaate hain. Peg-sheg lagate hain!”

Oh and you Dear Citizen. Thank you in advance. If you do pick the tab. Ghabrao nahi, there will be no pain. It will be like a painless injection on your bum.

And imagine I have borrowed Rs 50,000 crore. If you don’t rescue me, the bank I have borrowed from will go bust. And you will lose your money!

Remember what did that John Maynard Keynes say? “If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe your bank a million pounds, it has.”

Do you know the modern version of that? As The Economist magazine put it: “If you owe your bank a billion pounds everybody has a problem.”

Dear Citizen, I am your problem!

Yours truly,

An Indian Crony Capitalist

Postscript: Rajan has written Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists with Luigi Zingales. His other book is Fault Lines.

The column originally appeared in Vivek Kaul’s Diary on June 22, 2016

Some New Lessons on Jobs from an Old Economist

Many economists do not write in a language which is easily understandable. While John Maynard Keynes was a terrific writer (he is possibly the only economist who actually came up with one-liners), his magnum opus The General Theory of Money, Interest and Employment, which was published in 1936, isn’t such an easy read.

Believe you me! I have tried reading it several times over the years.

Just because the book isn’t an uneasy read, doesn’t mean that the points it is trying to make are not important. As Paul Samuelson, the first American economist to win a Nobel Prize, wrote about Keynes’ book, in a research paper titled Lord Keynes and the General Theory. As he wrote: “It is a badly written book, poorly organized; any layman who, beguiled by the author’s previous reputation, bought the book was cheated of his five shillings…It is arrogant, bad tempered, polemical and not overly generous in its acknowledgements. It abounds in mares’ nests and confusions…In short, it is a work of genius.”

Another economist whose work is not easy to read is the American economist Hyman Minsky, who died in 1996. The world discovered Minsky and his work in the aftermath of the financial crisis that started in September 2008 and so did I.

I tried reading Minsky’s magnum opus Stabilizing an Unstable Economy but could only read it half way through. I have been lucky to have since discovered other authors and economists who have tried to explain Minsky’s work in a language that I have been able to understand.

Over the last few days I have been reading L Randall Wray’s Why Minsky Matters—An Introduction to the Work of a Maverick Economist. Other than discussing Minsky’s views on banking and the financial system in great detail, Wray also discusses what Minsky thought of unemployment. Minsky’s interest in unemployment primarily came from the fact that he was brought up during The Great Depression, when the United States saw never before seen levels of unemployment and a huge contraction of the economy.

And what did Minsky think of the unemployment problem? As Wray writes: “His argument [i.e. Minsky’s] was that simply increasing the “employability” of the poor by providing training without increasing the supply of jobs would just redistribute unemployment and poverty. For every better trained worker who got a job, a worker with less training would become unemployed. Minsky was not arguing against better education and training—he was arguing that to reduce unemployment and poverty we need more jobs, too.”

Minsky also argued against the idea that “if the economy grows at a sufficiently robust pace, the jobs will automatically appear.” As Wray writes: “The notion that economic growth together with supply-side policies to upgrade workers and provide proper work incentives would be enough to eliminate poverty was recognized by Minsky at the time to be fallacious. Indeed, evidence suggests that economic growth mildly favours the “haves” over the “have-nots”—increasing inequality—and that jobs do not simply trickle down.”

How do things stack up in the Indian context? First and foremost, let’s look at the youth literacy number and how it has changed over the years. As per the Human Development Report, in 1990, the youth literacy rate (i.e. individuals in the age 15 and 24) was at 64.3% in 1990. This improved to 76.4% in 2003. In 2013, the youth literacy rate for men was at 88.4% and for women at 74.4%.

What these data points tell us clearly is that the education level of India’s youth has improved over the years. But has this led to more jobs? Answering this question is a little tricky given how bad Indian data on jobs is.

Nevertheless, as the Economic Survey released in February 2015 points out: “Regardless of which data source is used, it seems clear that employment growth is lagging behind growth in the labour force. For example, according to the Census, between 2001 and 2011, labour force growth was 2.23 percent (male and female combined). This is lower than most estimates of employment growth in this decade of closer to 1.4 percent.”

Hence, even though the youth education has improved over the years, this hasn’t led to an adequate number of jobs. This is clearly visible in all the engineers and MBAs that we produce without having the right jobs for them.

As Akhilesh Tilotia writes in The Making of India: “An analysis of the demand-supply scenario in the higher education industry shows significant capacity addition over the last few years: 2.4 million higher education seats in 2012 from 1.1 million in 2008.” In 2016, India will produce 1.5 million engineers. This is more than the United States (0.1 million) and China (1.1 million) put together.

The number of MBAs between 2012 and 2008 has also jumped to 4 lakh from the earlier 1 lakh. As Tilotia writes: “India faces a unique situation where some institutes (IITs,IIMs, etc.) are intensely contested while a large number of the recently-opened institutes struggle to fill seats…With most of the 3 million people wanting to pursue higher education now having an opportunity to do so, the big question that should…be asked…are all these trained personnel required? Our analysis seems to suggest that India may be over-educating its people relative to the current and at least the medium-term forecast requirement of the economy.”

This explains why many engineers and MBAs cannot find the right kind of jobs and have to settle for other jobs.

A major reason for the lack of enough jobs is the fact that Indian firms start small and continue to remain small. As Economist Pranab Bardhan writes in Globalisation, Democracy and Corruption: “Take the highly labour-intensive garments industry, for example. A combined dataset [of both the formal and informal sectors] shows that about 92 per cent of garment firms in India have fewer than eight employees.”

It’s only when small firms start to become bigger, will jobs be created. As the Economic Survey points out: “A major impediment to the pace of quality employment generation in India is the small share of manufacturing in total employment…This is significant given that the National Manufacturing Policy 2011 has set a target of creating 100 million jobs by 2022. Promoting growth of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME) is critical from the perspective of job creation which has been recognized as a prime mover of the development agenda in India.”

And this, as I keep saying, is easier said than done.

The column originally appeared on the Vivek Kaul Diary on January 20, 2016