Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The question being asked yesterday was “why is the rupee falling against the dollar”. The answer is very simple. The demand for American dollars was more than that of the Indian rupee leading to the rupee rapidly losing value against the dollar.

This situation is likely to continue in the days to come with the demand for dollars in India being more than their supply. And this will have a huge impact on the dollar-rupee exchange rate, which crossed 60 rupees to a dollar for the first time yesterday.

Here are a few reasons why the demand for dollars will continue to be more than their supply in the days to come.

a) The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) recently pointed out that

the foreign direct investment in India fell by 29% to $26 billion in 2012. When dollars come into India through the foreign direct investment(FDI) route they need to be exchanged for rupees. Hence, dollars are sold and rupees are bought. This pushes up the demand for rupees, while increasing the supply of dollars, thus helping the rupee gain value against the dollar or at least hold stable.

In 2012, the FDI coming into India fell dramatically. The situation is likely to continue in the days to come. The corruption sagas unleashed in the 2G and the coalgate scam hasn’t done India’s image abroad any good. In fact in the 2G scam telecom licenses have been cancelled and the message that was sent to the foreign investors was that India as a country can go back on policy decisions. This is something that no big investor who is willing to put a lot of money at stake, likes to hear.

Opening up multi-brand retailing was government’s other big plan for getting FDI into the country. In September 2012, the government had allowed foreign investors to invest upto 51% in multi-brand retailing. But between then and now not a single global retailing company has filed an application with the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), which looks at FDI proposals.

This scenario doesn’t look like changing as likely foreign investors struggle to make sense of the regulations as they stand today. Dollars that come in through the FDI route come in for the long run as they are used to set up new industries and factories or pick up a stake in existing companies. This money cannot be withdrawn overnight like the money invested in the stock market and the bond market.

b) There has been a lot of talk about the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) selling bonds to Non Resident Indians (NRIs) and thus getting precious dollars into the country. The trouble here is that any NRI who invests in these bonds will carry a huge amount of currency risk, given the rapid rate at which the rupee has lost value against the dollar.

Lets understand this through a simple example. An NRI invests $100,000 in India. At the point he gets money into India $1 is worth Rs 55. So $100,000 when converted into rupees, amounts to Rs 55 lakh. This money lets assume is invested at an interest rate of 10%. A year later Rs 55 lakh has grown to Rs 60.5 lakh (Rs 55 lakh + 10% interest on Rs 55 lakh). The NRI now has to repatriate this money back. At this point of time lets say $1 is worth Rs 60. So when the NRI converts rupees into dollars he gets $100,800 or more or less the same amount of money that he had invested. His return in dollar terms is 0.8%. The real return would be much lower given that this calculation doesn’t take the cost of conversion into account.

Hence, the NRI would have been simply better off by letting his money stay invested in dollars. This is the currency risk. To make it attractive for NRI investors to invest money in any such RBI bond, the interest on offer will have to be very high.

c) While the supply of dollars will continue to be a problem, the demand for them will continue to remain high. A major demand for dollars will come from companies which have raised loans in dollars over the last few years and now need to repay them. As the Business Standard reports “Beginning 2004, the central bank(i.e. RBI) has approved nearly $220 billion worth of external commercial borrowings and foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCB), at the rate of a little over $2 billion a month. Nearly two-thirds of this amount was approved in the past five years. Much of this ECB will come up for repayment this financial year, putting further pressure on the rupee.”

A lot of companies have raised foreign loans over the last few years simply because the interest rates have been lower outside India than in India. These companies will need dollars to repay their foreign loans as they mature.

The other thing that might happen is that companies which have cash, might look to repay their foreign loans sooner rather than later. This is simply because as the rupee depreciates against the dollar, it takes a greater amount of rupees to buy dollars. So if companies have idle cash lying around, it makes tremendous sense for them to prepay dollar loans. The trouble is that if a lot of companies decide to prepay loans then it will add to the demand for the dollar and thus put further pressure on the rupee.

d) India’s love for gold has been one reason behind significant demand for the dollar. Gold is bought and sold internationally in dollars. India produces very little gold of its own and hence has to import almost all the gold that is consumed in the country. When gold is imported into the country, it needs to be paid for in dollars, thus pushing up the demand for dollars. As this writer has argued in the past there is some logic for the fascination that Indians have had for gold. A major reason behind Indians hoarding to gold is high inflation. Consumer price inflation continues to remain high. Also, with the marriage season set to start over the next few months, the demand for gold is likely to go up. What can also add to the demand is the fall in price of gold, which will get those buyers who have not been buying gold because of the high price, back into the market. All this means a greater demand for dollars.

e) India has been importing a huge amount of coal lately to run its power plants. Indian coal imports shot up by 43% to 16.77 million tonnes in the month of May 2013, in comparison to the same period last year. Importing coal again means a greater demand for dollars.

The irony is that India has huge coal reserves which are not being mined. The common logic here is to blame Coal India Ltd, which more or less has had a monopoly to produce coal in India. The government has tried to encourage private sector investment in the sector but that has been done in a haphazard manner leading to the coalgate scam. This has delayed the bigger role that the private sector could have played in the mining of coal and thus led to lower coal imports.

The situation cannot be set right overnight. The major reason for this is the fact that the expertise to get a coal mine up and running in India has been limited to Coal India till now. To develop the same expertise in the private sector will take time and till then India will have to import coal, which will need dollars.

f) The government’s social sector policies may also add to a huge demand for dollars in the time to come. The procurement of wheat by the government this year has fallen by 33% to 25.08 million tonnes. This will not have any immediate impact given the huge amount of grain reserves that India currently has. But as and when right to food security becomes a legal right any fall in procurement will mean that the government will have to import food grains like wheat and rice, and this will again mean a demand for dollars. While this is a little far fetched as of now, but is a likely possibility and hence cannot be ignored.

These are fundamental issues which will continue to influence the dollar-rupee exchange rate in the days to come and do not have easy overnight kind of solutions. Of course, if the Ben Bernanke led Federal Reserve of United States, decides to go back to printing as many dollars as it is right now, then a lot of dollars could flow into India, looking for a higher return. But then, that is something not under the control of Indian government or its policy makers.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Imports

Petrol bomb is a dud: If only Dr Singh had listened…

Vivek Kaul

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government finally acted hoping to halt the fall of the falling rupee, by raising petrol prices by Rs 6.28 per litre, before taxes. Let us try and understand what will be the implications of this move.

Some relief for oil companies:

The oil companies like Indian Oil Company (IOC), Bharat Petroleum (BP) and Hindustan Petroleum(HP) had been selling oil at a loss of Rs 6.28 per litre since the last hike in December. That loss will now be eliminated with this increase in prices. The oil companies have lost $830million on selling petrol at below its cost since the prices were last hiked in December last year. If the increase in price stays and is not withdrawn the oil companies will not face any further losses on selling petrol, unless the price of oil goes up and the increase is not passed on to the consumers.

No impact on fiscal deficit:

The government compensates the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, BP and HP, for selling diesel, LPG gas and kerosene at a loss. Petrol losses are not reimbursed by the government. Hence the move will have no impact on the projected fiscal deficit of Rs 5,13,590 crore. The losses on selling diesel, LPG and kerosene at below cost are much higher at Rs 512 crore a day. For this the companies are compensated for by the government. The companies had lost Rs 138,541 crore during the last financial year i.e.2011-2012 (Between April 1,2011 and March 31,2012).

Of this the government had borne around Rs 83,000 crore and the remaining Rs 55,000 crore came from government owned oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL.

When the finance minister Pranab Mukherjee presented the budget in March, the oil subsidies for the year 2011-2012 had been expected to be at Rs Rs 68,481 crore. The final bill has turned out to be at around Rs 83,000 crore, this after the oil producing companies owned by the government, were forced to pick up around 40% of the bill.

For the current year the expected losses of the oil companies on selling kerosene, LPG and diesel at below cost is expected to be around Rs 190,000 crore. In the budget, the oil subsidy for the year 2012-2013, has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. If the government picks up 60% of this bill like it did in the last financial year, it works out to around Rs 114,000 crore. This is around Rs 70,000 crore more than the oil subsidy that the government has budgeted for.

Interest rates will continue to remain high

The difference between what the government earns and what it spends is referred to as the fiscal deficit. The government finances this difference by borrowing. As stated above, the fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 is expected to be at Rs 5,13,590 crore. This, when we assume Rs 43,580crore as oil subsidy. But the way things currently are, the government might end up paying Rs 70,000 crore more for oil subsidy, unless the oil prices crash. The amount of Rs 70,000 crore will have to be borrowed from financial markets. This extra borrowing will “crowd-out” the private borrowers in the market even further leading to higher interest rates. At the retail level, this means two things. One EMIs will keep going up. And two, with interest rates being high, investors will prefer to invest in fixed income instruments like fixed deposits, corporate bonds and fixed maturity plans from mutual funds. This in other terms will mean that the money will stay away from the stock market.

The trade deficit

One dollar is worth around Rs 56 now, the reason being that India imports more than it exports. When the difference between exports and imports is negative, the situation is referred to as a trade deficit. This trade deficit is largely on two accounts. We import 80% of our oil requirements and at the same time we have a great fascination for gold. During the last financial year India imported $150billion worth of oil and $60billion worth of gold. This meant that India ran up a huge trade deficit of $185billion during the course of the last financial year. The trend has continued in this financial year. The imports for the month of April 2012 were at $37.9billion, nearly 54.7% more than the exports which stood at $24.5billion.

These imports have to be paid for in dollars. When payments are to be made importers buy dollars and sell rupees. When this happens, the foreign exchange market has an excess supply of rupees and a short fall of dollars. This leads to the rupee losing value against the dollar. In case our exports matched our imports, then exporters who brought in dollars would be converting them into rupees, and thus there would be a balance in the market. Importers would be buying dollars and selling rupees. And exporters would be selling dollars and buying rupees. But that isn’t happening in a balanced way.

What has also not helped is the fact that foreign institutional investors(FIIs) have been selling out of the stock as well as the bond market. Since April 1, the FIIs have sold around $758 million worth of stocks and bonds. When the FIIs repatriate this money they sell rupees and buy dollars, this puts further pressure on the rupee. The impact from this is marginal because $758 million over a period of more than 50 days is not a huge amount.

When it comes to foreign investors, a falling rupee feeds on itself. Lets us try and understand this through an example. When the dollar was worth Rs 50, a foreign investor wanting to repatriate Rs 50 crore would have got $10million. If he wants to repatriate the same amount now he would get only $8.33million. So the fear of the rupee falling further gets foreign investors to sell out, which in turn pushes the rupee down even further.

What could have helped is dollars coming into India through the foreign direct investment route, where multinational companies bring money into India to establish businesses here. But for that the government will have to open up sectors like retail, print media and insurance (from the current 26% cap) more. That hasn’t happened and the way the government is operating currently, it is unlikely to happen.

The Reserve Bank of India does intervene at times to stem the fall of the rupee. This it does by selling dollars and buying rupee to ensure that there is adequate supply of dollars in the market and the excess supply of rupee is sucked out. But the RBI does not have an unlimited supply of dollars and hence cannot keep intervening indefinitely.

What about the trade deficit?

The trade deficit might come down a little if the increase in price of petrol leads to people consuming less petrol. This in turn would mean lesser import of oil and hence a slightly lower trade deficit. A lower trade deficit would mean lesser pressure on the rupee. But the fact of the matter is that even if the consumption of petrol comes down, its overall impact on the import of oil would not be that much. For the trade deficit to come down the government has to increase prices of kerosene, LPG and diesel. That would have a major impact on the oil imports and thus would push down the demand for the dollar. It would also mean a lower fiscal deficit, which in turn will lead to lower interest rates. Lower interest rates might lead to businesses looking to expand and people borrowing and spending that money, leading to a better economic growth rate. It might also motivate Multi National Companies (MNCs) to increase their investments in India, bringing in more dollars and thus lightening the pressure on the rupee. In the short run an increase in the prices of diesel particularly will lead higher inflation because transportation costs will increase.

Freeing the price

The government had last increased the price of petrol in December before this. For nearly five months it did not do anything and now has gone ahead and increased the price by Rs 6.28 per litre, which after taxes works out to around Rs 7.54 per litre. It need not be said that such a stupendous increase at one go makes it very difficult for the consumers to handle. If a normal market (like it is with vegetables where prices change everyday) was allowed to operate, the price of oil would have risen gradually from December to May and the consumers would have adjusted their consumption of petrol at the same pace. By raising the price suddenly the last person on the mind of the government is the aam aadmi, a term which the UPAwallahs do not stop using time and again.

The other option of course is to continue subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene. As a known stock bull said on television show a couple of months back, even Saudi Arabia doesn’t sell kerosene at the price at which we do. And that is why a lot of kerosene gets smuggled into neighbouring countries and is used to adulterate diesel and petrol.

If the subsidies continue it is likely that the consumption of the various oil products will not fall. And that in turn would mean oil imports would remain at their current level, meaning that the trade deficit will continue to remain high. It will also mean a higher fiscal deficit and hence high interest rates. The economic growth will remain stagnant, keeping foreign businesses looking to invest in India away.

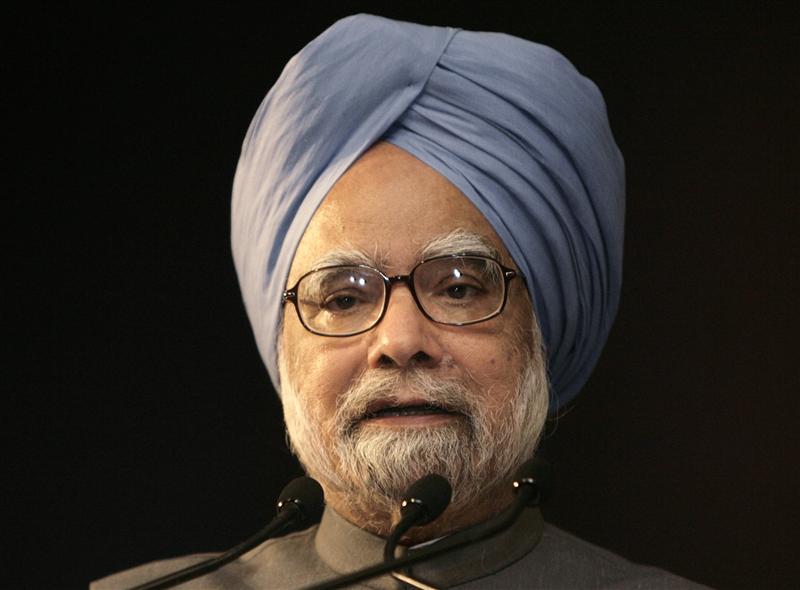

Manmohan Singh as the finance minister started India’s reform process. On July 24, 1991, he backed his “then” revolutionary proposals of opening up India’s economy by paraphrasing Victor Hugo: “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

Good economics is also good politics. That is an idea whose time has come. Now only if Mr Singh were listening. Or should we say be allowed to listen..

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on May 24,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/petrol-bomb-is-a-dud-if-only-dr-singh-had-listened-319594.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])