If politicians and corporates are to be believed then India’s much beleaguered economy can be put back on track only if the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) brought down interest rates. The finance minister P Chidambaram did not mince words when he said in an interview to The Economic Times that “reduction in interest rates will certainly help get us to 6.5% (economic growth).” In another article in the Business Standard several CEOs (including those of real estate firms) have come on record to say that the RBI should cut interest rates in order to revive the economy.

The RBI meets next on March 19. And both CEOs and politicians seem to be clamouring for a repo rate cut. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks. So the logic is that once the RBI cuts the repo rate (as it did when the last time it met in late January) the banks will get around to passing that cut by bringing down the interest rates they charge on their loans. Given this people will borrow and spend more. They will buy more houses. They will buy more cars. They will buy more two wheelers. They will buy more consumer durables. Companies will also borrow and expand. All this borrowing and spending will revive the economic growth and the economy will grow at 6.5% instead of the 4.5% it grew at between October and December, 2012. And we will all live happily ever after.

Now only if life was as simple as that.

Repo rate at best is a signal from the RBI to banks. When it cuts the repo rate it is sending out a signal to the banks that it expects interest rates to come down in the time to come. Now it is up to the banks whether they want to take that signal or not. And turns out they are not.

Several banks have recently been raising interest rates on their fixed deposits. Of course, if banks are raising interest rates on their deposits, they can’t be cutting them on their loans, given money raised from deposits is used to fund loans. And hence interest rates on loans has to be higher than those on deposits. Banks have raised interest rates despite the fact that the RBI cut the repo rate by 25 basis points (one basis point is equal to one hundreth of a percentage) when it last met on January 29, 2013.

So why are banks raising interest rates when the RBI has given the opposite signal? The answer for that lies in the Economic Survey released on February 27, 2013. The gross domestic savings of the country were at 36.8% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during the course of 2007-2008 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2007 and March 31, 2008). They had fallen to 30.8% of the GDP during the course of 2011-2012 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012). I wouldn’t be surprised if they have fallen further once figures for the current financial year become available.

The household savings (i.e. the money saved by the citizens of India) have also been falling over the last few years. In the year 2009-2010 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010) the household savings stood at 25.2% of the GDP. In the year 2011-2012, the household savings had fallen to 22.3% of the GDP.

What this means is that the country as a whole is saving lesser money than it was before. A straightforward explanation for this is the high inflation that has prevailed over the last few years. People are possibly spending greater proportions of their income to meet the rising expenses and that has lead to a lower savings rate.

Interestingly the financial savings have been falling at an even faster rate than overall savings. As the Economic Survey points out “Within households, the share of financial savings vis-à-vis physical savings has been declining in recent years. Financial savings take the form of bank deposits, life insurance funds, pension and provident funds, shares and debentures, etc. Financial savings accounted for around 55 per cent of total household savings during the 1990s. Their share declined to 47 per cent in the 2000-10 decade and it was 36 per cent in 2011-12. In fact, household financial savings were lower by nearly Rs 90,000 crore in 2011-12 vis-à-vis 2010-11.”

One reason for this (explained in the Economic Survey) is that a lot of savings have been going into gold. And why have the savings been going to gold? The government would like us to believe that it is our fascination for gold that is driving our savings into gold. But then our fascination for gold is not a recent phenomenon. Indians have always liked gold.

People buy gold as a hedge against inflation. When inflation is high the real returns on fixed income instruments are low. Real return is the difference between the rate of interest offered on let us say a fixed deposit, minus the prevailing rate of inflation.

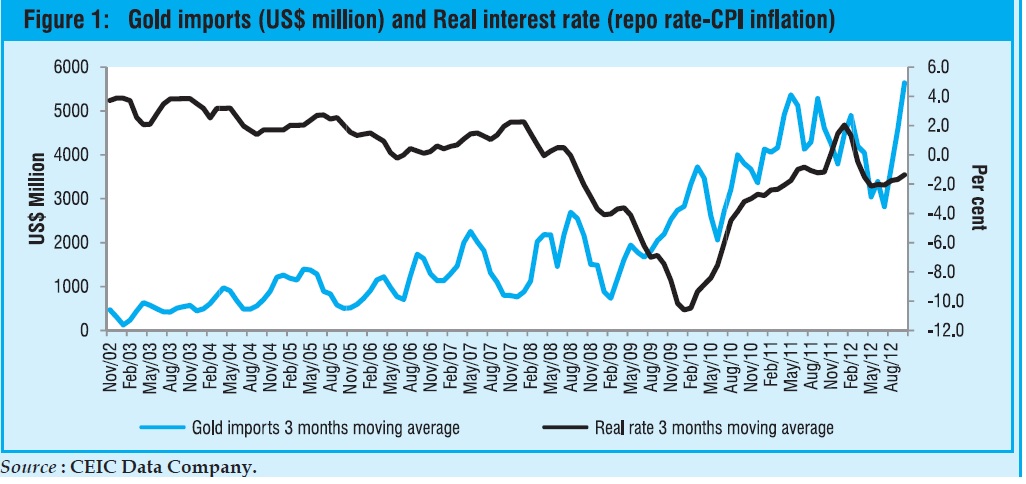

As the Economic Survey puts it “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments. This is reflected in the negative correlation between rising(gold) imports and falling real rates.” (As can be seen from the following table).

What this means is that when inflation is high, the real return on fixed income investments like fixed deposits is low. Consumer Price Inflation has been close to 10% in India over the last few years. And this has meant that investment avenues like fixed deposits have been made unattractive, leading people to divert their savings into gold. “The overarching motive underlying the gold rush is high inflation…High inflation may be causing anxious investors to shun fixed income investments such as deposits and even turn to gold as an inflation hedge,” the Economic Survey points out.

What does this mean in the context of b

anks? It means that banks have had a lower pool of savings to borrow from. One because the overall savings have come down. And two because within overall savings the financial savings have come down at a much faster rate due to lower real rates of interest, after adjusting for inflation. This means that banks need to offer high rates of interest on their fixed deposits to make it attractive for people to deposit their money into banks. It is a simple case of demand and supply.

And who is the cause for all the inflation that the country has seen over the last few years and continues to see? Not you and me.

High inflation has been caused by the burgeoning subsidies provided by the government. The total subsidy in 2006-2007(i.e. The period between April 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007) stood at Rs 53,462.60 crore. This has gone up by nearly five times to Rs 2,57,654.43 crore for the year 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013).

All this expenditure of the government has landed up in the hands of people and created inflation. The Economic Survey admits to the same when it states “With the subsidies bill, particularly that of petroleum products, increasing, the danger that fiscal targets would be breached substantially became very real in the current year. The situation warranted urgent steps to reduce government spending so as to contain inflation.” So the Economic Survey equated the high government spending to inflation.

The subsidy bill for the year 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014) is expected to be at Rs 2,31,083.52 crore. This is number seems to be underestimated as this writer has explained before. And so the inflationary scenario is likely to continue.

Given that people will want to deploy their savings to other modes of investment rather than fixed deposits. And hence banks will have to continue offering higher interest rates to get people interested in fixed deposits.

As the Economic Survey points out “The rising demand for gold is only a “symptom” of more fundamental problems in the economy. Curbing inflation, expanding financial inclusion, offering new products such as inflation indexed bonds, and improving saver access to financial products are all of paramount importance.”

To conclude, there is very little that the D Subbarao led RBI can do to push down interest rates. In fact interest rates are totally in the hands of the government. If the government can somehow control inflation, interest rates will start to come down automatically. For that to happen subsidies in particular and the high government expenditure in general, will have to be controlled. And that is not going to happen anytime soon.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 4, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets at @kaul_vivek)