I need to confess at the very start that I should have written this column a few days back. But more important things happened and this idea had to take a back seat. Nevertheless, as they say, it’s better late than never.

So, let’s start this column with two examples—one borrowed and one personal. The idea behind both the examples is to illustrate two concepts from behavioural economics—contrast effect and anchoring.

In the book The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less, Barry Schwartz discusses an example of a high-end catalog seller, who was selling an automatic bread maker for $279. As he writes “Sometime later, the catalog seller began to offer a large capacity, deluxe version for $429. They didn’t sell too many of these expensive bread makers, but sales of the less expensive one almost doubled! With the expensive bread maker serving as anchor, the $279 machine had become a bargain.”

Essentially, there are two things that are happening here. The buyer first gets “anchored” on to high price of the deluxe version of bread maker which is priced at $429. After this the contrast effect takes over. The bread maker priced at $279 seems cheaper than the deluxe version and people end up buying it.

As John Allen Paulos writes in A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market “Most of us suffer from a common psychological failing. We credit and easily become attached to any number we hear. This tendency is called “anchoring effect.””

And once an individual is anchored on to a number, he then tends to compare it with other numbers that are thrown at him. Marketers exploit this very well. As Schwartz points out “When we see outdoor gas grills on the market for $8,000, it seems quite reasonable to buy one for $1,200. When a wristwatch that is no more accurate than one you can buy for $50 sells for $20,000, it seems reasonable to buy one for $2,000. Even if companies sell almost none of their highest-priced models, they can reap enormous benefits from producing such models because they help induce people to buy cheaper ( but still extremely expensive) ones.”

This was the borrowed example. Now let me discuss the personal example. Sometime in May 2006, I was suddenly asked to leave the apartment that I lived in because the landlord had not been paying the society charges for a very long time. And thus started the search for another apartment to rent. Affordable apartments in Central Mumbai tend to be in buildings that are not in best shape.

Given this, real estate agents use a trick where they try and exploit the contrast effect. The first few apartments that they show are in a really bad shape. After having done this they show an apartment which is slightly better than the ones shown earlier, but the rent is significantly higher.

The attractiveness of the apartment shown later is increased significantly by showing a few “run down” apartments earlier.

The idea behind sharing these two examples was to explain the idea of anchoring and contrast effect. I hope both these concepts are clear by now. Now let me move on to real issue that I want to talk about in this column.

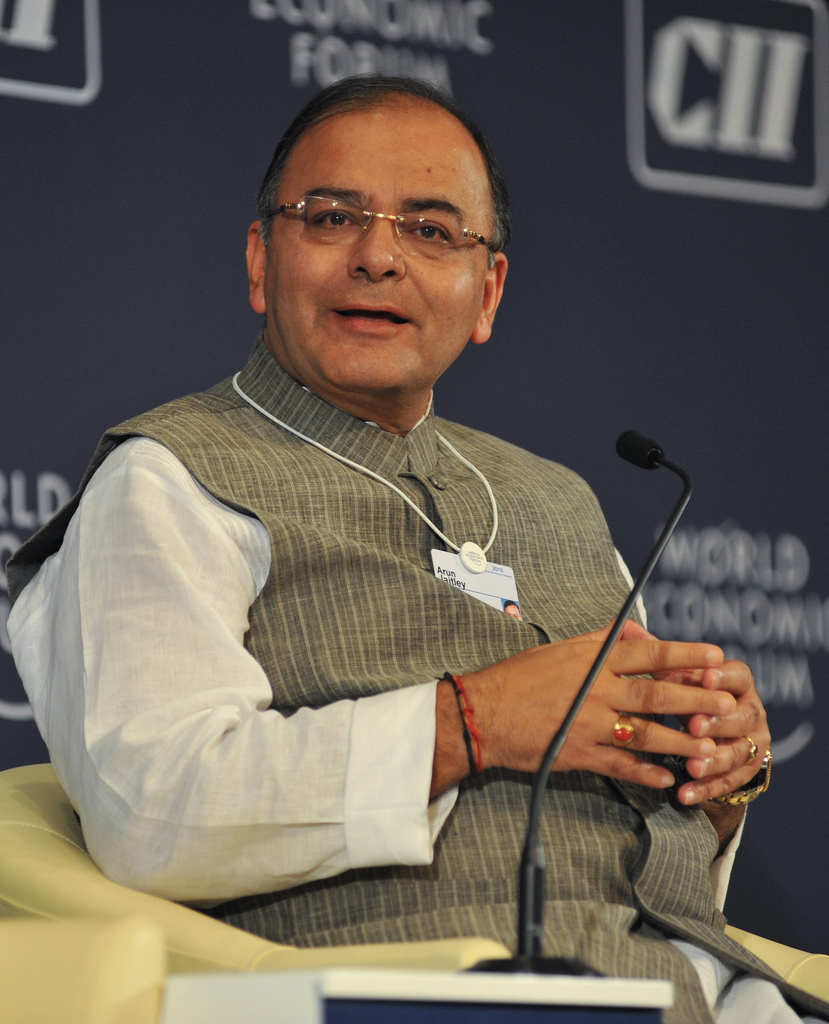

On November 18, the finance minister Arun Jaitley said in a speech “Inflation, especially food inflation, has moderated in the last few months and global fuel prices have also come down. Therefore, if RBI, which is a highly professional organisation, in its wisdom decides to bring down the cost of capital, it will give a good fillip to the Indian economy.”

In simple English, Jaitley, as he has often done in the past, was asking the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to cut the repo rate. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks. The idea is essentially that at lower interest rates, people will borrow and spend more, and companies will invest and expand. This will lead to faster economic growth. While this sounds good in theory, as I had argued a few days back, it isn’t as simple it is made out to be.

One argument offered by those asking the RBI to cut interest rates is that inflation as measured by the consumer price index has fallen to 5.52% in October 2014. It was at 6.46 % in September 2014 and 10.17% in October 2013.

Nevertheless, is inflation really low? Or are Jaitley and others like him who have been demanding an interest rate cut just becoming victims of anchoring and the contrast effect?

The inflation figure of greater than 10% which had been prevalent over the last few years is anchored into their minds. And in comparison to that an inflation of 5.52% does sound low. Hence, the contrast effect is at work here.

Further, it is worth remembering that this so called low inflation has been prevalent only for a few months. Chances are that food prices might start rising again. The government has forecast that the output of kharif crops will be much lower than last year and this might start pushing food prices upwards all over again. Also, recent data showsthat vegetable and cereal prices have started rising again because of the delayed monsoon.

Central banks of developed countries typically tend to have an inflation target of 2%. In the recent past they have been unable to meet even that number. Large parts of the world might now be heading towards deflationary scenario, where prices will fall.

In October, the consumer price inflation in China stood at 1.6%, well below the targeted 3.5%. Also, in January earlier this year the Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework set up by RBI had recommended that the Indian central bank should set an inflation target of 4%, with a band of +/- 2 per cent around it .

The committee had said “transition path to the target zone should be graduated to bringing down inflation from the current level of 10 per cent to 8 per cent over a period not exceeding the next 12 months and 6 per cent over a period not exceeding the next 24 month period before formally adopting the recommended target of 4 per cent inflation with a band of +/- 2 per cent.”

Once, these factors are taken into account, the latest inflation number of 5.52% as measured by the consumer price index, isn’t really low, even though it seems to be low in comparison to the very high inflation that had prevailed earlier. But as explained this is more because of anchoring and the contrast effect at work.

Also, as I had written earlier, more than anything people still haven’t come around to the idea of low inflation, given that inflationary expectations(or the expectations that consumers have of what future inflation is likely to be) continue to remain on the high side.

As per the Reserve Bank of India’s Inflation Expectations Survey of Households: September – 2014, the inflationary expectations over the next three months and one year are at 14.6 percent and 16 percent. In March 2014, the numbers were at 12.9 percent and 15.3 percent. Hence, inflationary expectations have risen since the beginning of this financial year.

If inflationary expectations are to come down, then low inflation needs to be prevail for some time. Just a few months of low inflation is not enough. As RBI governor Raghuram Rajan had said in a speech in February this year “ the best way for the central bank to generate growth in the long run is for it to bring down inflation…Put differently, in order to generate sustainable growth, we have to fight inflation first.”

Rajan is trying to do just that, and it’s best that Jaitley allows him to do that, instead of demanding a cut in interest rates every now and then.

The article appeared originally on www.equitymaster.com on Nov 21, 2014