It is fashionable in Delhi circles these days to ask for an an interest rate cut at a drop of a hat. The finance minister Arun Jaitley like his predecessor P Chidambaram likes to remind the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) now and then that the time is just right for a rate cut.

In an interview to The Times of India late last week Jaitley said “”Currently, interest rates are a disincentive. Now that inflation seems to be stabilizing somewhat, the time seems to have come to moderate the interest rates.”

Before Jaitley, the senior columnist Prem Shankar Jha became the newest interest-rate-wallah on the block and in a column in The Times of India held the RBI responsible for India’s slow economic growth over the last few years. As he wrote“[The] Indian economy is not on the road to recovery. The reason is the sustained high interest rate regime of the past four years. Industry has been begging for cuts in the cost of borrowing since March 2011… On August 5, RBI governor Raghuram Rajan surprised the country by announcing that he would not lower interest rates, because at 8% consumer price inflation was still too high.”

I guess Jha must have been among the few people surprised by Rajan’s decision given that among those who follow the workings of the Indian central bank closely, almost no one had expected Rajan to cut interest rates.

The premise on which interest-rate-wallahs work is that at lower interest rates people will borrow and spend more, which will lead to economic growth. But the entire premise that low interest rates will lead to a pick up in consumption and hence, higher economic growth, doesn’t really hold. (As I have explained here). Jaitley believes that “expansion in real estate will take place significantly only if the interest rates come down a little.”

This is what the real estate companies also like to believe. But the basic point is that people are not buying homes because home prices have risen way above what they can afford. As I have explained in the past, for an average Mumbaikar it currently takes around 34 years annual income to buy a home to live in. This is true for other cities as well, though the situation maybe a little better than that in Mumbai. So even a major cut in interest rates is not going to lead people buying homes to live in unless real estate prices fall. This is something that Arun Jaitley as the finance minister of this country needs to understand.

Having said that, those looking to move their black money around will always look at investing in real estate and for them the interest rates really don’t matter.

The other big reason offered is that companies can borrow at lower rates of interest. The idea being that lower interest rates might encourage companies to borrow and expand. Again it needs to be realized that companies don’t always decide to expand just because money is available at low interest rates, especially in difficult times as these.

Factors like ease of doing business and consumer demand play an important role. As I have explained in the past, due to many years of high inflation consumer demand in India continues to remain subdued. And unless it starts to pick up, there is no real reason for companies to expand.

Also, it is worth remembering here that a some of the major business groups in India have already borrowed a lot of money and are having tough time paying interest on the debt they already have. Hence, where is the question of borrowing more?

The bigger question that interest-rate-wallahs tend to ignore is how much control does the RBI really have over interest rates that banks pay their depositors and in turn charge their borrowers? Over the last few weeks, banks have cut interest rates on their fixed deposits. The list includes State Bank of India, Punjab National Bank and Central Bank of India. (You can read about here, here and here). The Indus Ind Bank also cut the interest it pays on its savings account to 4.5% from the earlier 5.5% for a daily balance of up to Rs 1 lakh, starting September 1, 2014.

All these cuts in interest rates have happened despite the RBI maintaining the repo rate at 8%. Repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks. So what has changed that has allowed these banks to cut the interest rates at which they borrow?

Let’s look at some numbers. As on October 3, 2014, over a period of one year, the loans given by banks rose by 9.87%. During the same period the deposits raised by banks rose by 11.54%. How was the situation one year back? As on October 4, 2013, over a period of one year, the loans given by banks had risen by 15.18%. During the same period the deposits had grown by 12.9%.

Hence, the rate of loan growth for banks has fallen much faster than the rate at which their deposit growth has fallen. Given this, it is not surprising that banks are cutting fixed deposit rates, given that their rate of loan growth is falling at a much faster rate.

As Henry Hazlitt writes in Economics in One Lesson “Just as the supply and demand for any other commodity are equalized by price, so the supply of demand for capital are equalized by interest rates. The interest rate is merely a special name for the price of loaned capital. It is a price like any other.”

As Hazlitt further points out “If money is kept…in…banks…the banks are eager to lend and invest it. They cannot afford to have idle funds.”

Hence, given that the rate of loan growth is much slower than the rate of deposit growth, it is not surprising that banks are cutting interest rates on their fixed deposits. Given this, the impact that RBI’s repo rate has on interest rates is at best limited. It is more of a broad indicator from the RBI on which way it thinks interest rates are headed.

Further, it also needs to be remembered that financial savings in India have fallen dramatically over the last few years. The latest RBI annual report points out that “the household financial saving rate remained low during 2013-14, increasing only marginally to 7.2 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 from 7.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 and 7.0 per cent of GDP in 2011-12…the household financial saving rate [has] dipped sharply from 12 per cent in 2009-10.”

Household financial savings is essentially the money invested by individuals in fixed deposits, small savings scheme, mutual funds, shares, insurance etc. It has come down from 12% of the GDP in 2009-10 to 7.2% in 2013-14. A major reason for the fall has been the high inflation that has prevailed since 2008.

The rate of return on offer on fixed income investments(like fixed deposits, post office savings schemes and various government run provident funds) has been lower than the rate of inflation. This led to people moving their money into investments like gold and real estate, where they expected to earn more. Hence, the money coming into fixed deposits slowed down leading to a situation where banks could not cut interest rates., given that their loan growth continued to be strong.

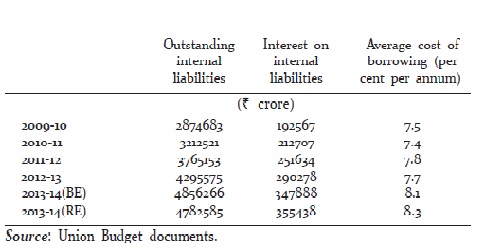

What also did not help was the fact that the borrowing requirements of the government of India kept growing over the years.

The RBI was not responsible for any of this. The only way to bring down interest rates is by ensuring that inflation continues to remain low in the months and the years to come. If this happens, then money flowing into fixed deposits will improve and that, in turn, will help banks to first cut interest rates they offer on their deposits and then on their loans.

The government needs to play an important part in the efforts to bring down inflation. In fact, it has been working on that front. In a recent research report analysts Abhay Laijawala and Abhishek Saraf of Deutsche Bank Market Research write that the “the government is firmly ‘walking the talk’ on fiscal consolidation” through a spate of “recent administrative moves on curbing food inflation (such as fast liquidation of surplus foodstock, modest single-digit hike in MSPs, an effort to eliminate fruits and vegetables from ambit of APMC etc.)”

This is very important given that once inflation remains low for an extended period of time, only then will inflationary expectations (or the expectations that consumers have of what future inflation is likely to be) be reined in. And consumer demand is likely to pick up after this.

The Reserve Bank of India’s Inflation Expectations Survey of Households: September – 2014 which was a survey of 4,933 urban households across 16 cities, and which captures the inflation expectations for the next three-month and the next one-year period. The median inflation expectations over the next three months and one year are at 14.6 percent and 16 percent. In March 2014, the numbers were at 12.9 percent and 15.3 percent. Hence, inflationary expectations have risen since the beginning of this financial year.

To conclude, RBI seems to have become everyone’s favourite punching bag even though its impact on setting interest rates is rather limited. It is time that interest-rate-wallhas like Jaitley and Jha come to terms with this.

This an updated version of a column that appeared on Oct 22, 2014. You can read the original column here

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)