For a story to go viral on the social media, it needs to be simple and straightforward. In fact, the story should be summarisable in a headline.

The story of Bangladesh’s per capita income overtaking that of India is precisely that kind of story. John Lanchester defines per capita income in his book How To Speak Money as: “The total Gross Domestic Product(GDP) of a country divided by the number of people in the country…It is a measure of how rich the country’s citizens are on average.”

In simple terms what this story told us is that the average income of Bangladesh was more than that of India and hence, an average Bangladeshi was richer than an average Indian (Actually, it may not be so. You can understand why I say so here. But that’s what the conclusion drawn was).

No wonder the story got picked up and no wonder it has become viral.

Dear reader, you might be wondering by now if the story is that simple why am I writing about it? The answer will soon become clear.

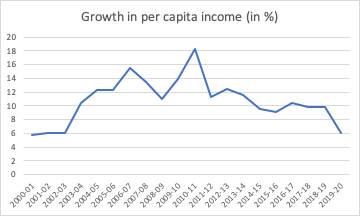

Let’s first take a look at the following chart. It plots the per capita income of India and Bangladesh.

Bangladesh overtakes India?

Source: International Monetary Fund.

A few days back, the International Monetary Fund published the World Economic Outlook (WEO) for October 2020. It also released a lot of data along with it. The above chart is plotted using data from the database which accompanied the release of the WEO.

As per the above chart, India’s per capita income in 2020 will be $ 1,876.53. In comparison, the per capita income of Bangladesh during 2020 will be $1,887.97. This is around 0.6% more than the Indian per capita income. The difference is very small but there is a difference.

All the song and dance about India versus Bangladesh came from this data point. Everyone picked up this data point, the media, the economists, the analysts, the influencers and finally, the politicians as well.

But what no one bothered to elaborate on is that the WEO data also tells us that India’s per capita income will be higher than Bangladesh between 2021 and 2023, and in 2024, Bangladesh will overtake India again.

The point is that there is a lot of nuance in this data, which the headline of Bangladesh per capita income overtaking India’s, doesn’t really summarise. But who was bothered. It made for a great story and people ran with it. As the old newspaper cliché goes, if it bleeds, it leads.

Nevertheless, there is one thing that I haven’t told you up until now. What is that? The per capita income in the above chart and what we have been discussing until now, is in nominal terms (or current prices). This basically means that it hasn’t been adjusted for inflation. The inflation in Bangladesh since 2014 has been higher than India. The following chart plots that.

Faster price rise in Bangladesh

Source: International Monetary Fund.

A higher inflation reduces the purchasing power of a currency and that needs to be adjusted for. The International Monetary Fund provides data after adjusting for inflation and purchasing power parity (that is how much does a currency really buy), as well.

Take a look at the following chart, it plots the per capita income of India and Bangladesh, adjusted for inflation, in constant terms.

India is ahead of Bangladesh

Source: International Monetary Fund. Purchasing power parity; 2017 international dollar.

Once we adjust for inflation and purchasing power, the Indian per capita income is higher than that of Bangladesh. The trouble is that by now this story has become too complicated to go viral.

It’s no longer as simple as Bangladesh’s per capita income overtaking India. And India’s per capita income continuing to be higher than that of Bangladesh is not much of a story. I mean after all we are competing with China and not with a puny Bangladesh. (I am saying all this to explain why a certain kind of story in economics tends to go viral on the social media. We all want simple binary explanations that do not tax our minds much).

The story doesn’t end here. There is more to come. While Bangladesh’s per capita income continues to be lower than that of India, it is rapidly catching up. Let’s take a look at the following chart. It plots the ratio of the Indian per capita income to the Bangladeshi per capita income, using data used in the previous chart which has been adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity.

Bangladesh is catching up

Source: Author calculations on IMF data.

As per this chart, India’s per capita income was 43% more than that of Bangladesh in 2016. The difference has been falling ever since. In 2021, the difference will fall to 20%. This basically means that Bangladesh is rapidly catching up on India.

Bangladesh has been doing better than India on a whole host of non-income indicators.

1) As per the Human Development Index, India’s life expectancy at birth in 2018 was 69.4 years. That of Bangladesh was 72.3.

2) This is primarily because India has a higher mortality rate of children under 5 years. In the Indian case, the mortality rate is 39.4 per 1,000 live births. In Bangladesh it is at 32.4. This means that fewer children die in Bangladesh before achieving the age of five. This explains why average life expectancy in Bangladesh is higher.

3) The child malnutrition rate in Bangladesh (% of children under 5) in Bangladesh is 36.2%. In India it is at 37.9%. A greater proportion of Indian children under the age of 5 are malnourished. Of course, the absolute numbers are much much more in the Indian case.

4) Bangladesh has much higher immunisation rates for diseases like DPT and measles than India. The rate of malaria incidence is higher in India, with 7.7 per 1,000 people being at risk. In case of Bangladesh, 1.9 per 1,000 people are at risk. The rate of tuberculosis incidence is higher in Bangladesh.

5) Interestingly, the current health expenditure in case of Bangladesh is at 2.4% of its GDP. India spends 3.7% of its GDP. But clearly the money is being much better spent in Bangladesh.

6) Bangladesh also does a lot better on a whole host of work and employment indicators. The employment to population ratio in case of Bangladesh is 56.2%. In case of India it is 50.6%. Clearly a greater proportion of Bangladeshi population is employed.

7) This is reflected in the higher labour force participation rate (people of the age of 15 and above it, who are a part of the labour force) of 58.7% in case of Bangladesh. In case of India it is at 51.9%. More interestingly, the labour force participation rate in case of Bangladeshi women is at a much higher 36% against 23.6% in India.

8) 55.5% of the employment in Bangladesh can be categorised as vulnerable employment. In case of India it is at 76.7%. A higher proportion of Indian jobs are at the risk of being lost.

9) 33.4% of the statutory age pension population in Bangladesh gets pension. In India, it is at 25.2%. On the flip side, a higher proportion of non-agricultural employment in Bangladesh is informal (at 91.3% against India’s 74.8%).

10) 43.9% of India’s labour force is employed in agriculture against Bangladesh’s 40.2%. Clearly, Bangladesh has been able to move people away from agriculture into other ways of earning money faster than India. 39.4% of the country’s employment is in the services sector against India’s 31.5%.

11) The sex ratio in Bangladesh (male to female ratio) at 1.05 is better than India’s 1.10. In India there are 100 females per 110 males on an average. In Bangladesh there are 100 females per 105 males on an average.

12) 97.3% of the population in Bangladesh has mobile phone subscriptions. In India it is at 86.9%. Having said that, India’s internet penetration at 34.5% of the population is higher than Bangladesh’s 15%.

13) The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality within a country, is lower in case of Bangladesh at 32.4 against India’s 35.7.

14) When it comes to schooling, the expected years of schooling in India stands at 12.3 years. In case of Bangladesh it is slightly lower at 11.2 years. Having said that, the rate of literacy among adults (15 years and older) in Bangladesh is at 72.9% against India’s 69.3%. This, despite the fact that the government expenditure on education in India amounts to 3.8% of the GDP, against Bangladesh’s 1.5% of the GDP. One possible explanation for this lies in the fact that India spends much more on higher education than Bangladesh.

15) The mean years of schooling for females in Bangladesh is at 5.3 years against India’s 4.7 years. On the flip side, the primary school dropout rate in Bangladesh is much higher at 33.8% against 12.3% in India’s case.

16) All the above data has been taken from the Human Development Index. With a score of 0.647 India ranks 129th on the index. Bangladesh on the other hand has a score of 0.614 and ranks 135th on the index. But there is a simple explanation for this. As Swati Narayan wrote in The Indian Express, in February this year: “While, technically, on the Human Development Index, Bangladesh scores marginally less, this is largely because the index merges income and non-income parameters.”

On many non-income indicators (as we have seen above) Bangladesh comes out better than India. Take the case of the Global Hunger Index. India ranked 94th among 107 countries. Bangladesh was at the 88th spot. Both countries have a level of hunger that is serious. But in case of Bangladesh, the situation is a little better. Even the World Happiness Report reported Bangladesh to be a much happier country than India.

17) India’s exports are much more than that of Bangladesh. But when it comes to exporting readymade garments (something that can create a huge number of jobs), Bangladesh has been doing much better than India for a while now. Take a look at the following chart, which compares India and Bangladesh’s garment exports.

Bangladesh beats India

Source: Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy and the Dhaka Tribune.

The reasons for this success are explained in this piece I wrote for Mint.

Not for a moment am I suggesting that India is doing worse than Bangladesh on all parameters. It is not. But over the last two decades Bangladesh has managed to narrow the gap on many parameters especially those on the social, health, gender and work front.

If this continues, in the years to come it won’t be difficult for Bangladesh to overtake India’s per capita income, especially if we continue with what has now become the all-encompassing nothing is wrong and all is well rhetoric.

Of course, meanwhile both sides will continue to spin data in ways that are useful to them. The chances that you will see spin with data are more these days than the chance of a ball spinning on a cricket pitch.

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.