Vivek Kaul

On September 12, 2008, the Bank of England, had total assets worth £83.8 billion on its books. In the six years since then, the total assets of the British central bank have gone up by a whopping 385.6% to £ 404.3 billion, as on September 17, 2014.

Things haven’t been much different in the United States. The Federal Reserve of United States had assets worth $905.3 billion as on September 3, 2008. Since then it has jumped to $4.45 trillion, as on September 17,2014. An increase of close to 392%.

The total assets of the Bank of Japan have more than doubled since the start of 2011. In January 2012, the total assets of the Japanese central bank had stood at 128 trillion yen. Since then, it has more than doubled to 275.9 trillion yen at the end of August 2014.

Since the start of the financial crisis in the middle of September 2008, Western central banks have printed money big time. This money has been pumped into the financial system by buying bonds. These bonds have ended up as assets on the balance sheet of central banks.

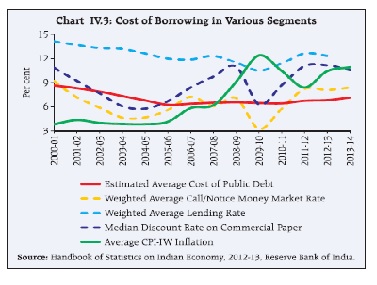

The idea behind this, as I have often mentioned in the past, was to drive down long term interest rates, leading to people borrowing and spending more at lower interest rates. This would, in turn, lead to economic growth, the hope was.

When central banks started printing money, the Cassandras (which included yours truly as well) started to point out that the era of high inflation was on its way. The logic offered was fairly straight forward. With so much money being pumped into the financial system, it would lead to a lot of money chasing the same amount of goods and services in the economy, and that would drive prices up at a rapid rate, and lead to high inflation.

But that did not turn out to be the case. The Western world had already taken on huge loans before the financial crisis broke out and was in no mood to borrow and spend all over again.

This lack of inflation has been used by central banks to print and pump more money into the financial system. The hope now is that with all the money that has been pumped into the financial system some inflation will be created. This inflation will lead to people spending more. The logic here is that no one wants to pay a higher price for a product, and if prices are going up or likely to go up, people would rather buy the product now than wait. And this will lead to economic growth. That in short is the gist of what the policy of the Western central banks has been all about over the last few years.

The economist Milton Friedman had suggested that a recessionary situation could be fought even by printing and dropping money out of a helicopter, if the need be, to create inflation.

And this is what Western central banks have done since September 2008, in the hope of reviving economic growth. While they may not have been able to create “some” conventional inflation as they wanted to, there is a lot else that has happened. And that needs to be understood.

When central banks print money, they do so with the belief that money is neutral. So, in that sense, it does not really matter who is standing under the helicopter when the money is printed and dropped into the economy. But the Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon who lived during the early eighteenth century, showed that money wasn’t really neutral and that it mattered where it was injected into the economy.

Cantillon made this observation on the basis of all the gold and silver coming into Spain from what was then called the New World (now South America). When money supply increased in the form of gold and silver, it would first benefit the people associated with the mining industry, i.e., the owners of the mines, the adventurers who went looking for gold and silver, the smelters, the refiners and the workers at the gold and silver mines.

These individuals would end up with a greater amount of gold and silver , i.e., money. They would spend this money and thus drive up the prices of meat, wine, wool, wheat, etc.

This rise in prices would have impacted even people not associated with the mining industry, even though they wouldn’t have seen a rise in their incomes, like the people associated with the mining industry had.

This is referred to as the Cantillon Effect. As analyst Dylan Grice puts it : “Cantillon, writing before the days of Adam Smith, was the first to articulate it. I find it very puzzling that this insight has been ignored by the economics profession. Economists generally assume that money is neutral. And Milton Friedman’s allegory about the helicopter drop of money raising the general price level completely ignores the question of who is standing under the helicopter.”

The money printing that has happened in recent years has been unable to meet its goal of trying to create consumer-price inflation. But it has benefited those who are closest to the money creation. This basically means the financial sector and anyone who has access to cheap credit.

Institutional investors have been able to raise money at close to zero percent interest rates and invest it in financial assets all over the world, driving up the prices of those assets and made money in the process.

As the economist William Bonner put it in a column he wrote in early 2013: “The Fed creates new money (not more wealth… just new money). This new money goes into the banking system, pretending to have the same value as the money that people worked for. And people with good connections to the banks take advantage of the cheap credit this new money creates to aid financial speculation.”

This financial speculation has led to massive stock market rallies all over the world. As I wrote in a piece last week “The Dow Jones Industrial Average, America’s premier stock market index, has rallied more than 30 percent since October 2012. This when the American economy hasn’t been in the best of shape. The FTSE 100, the premier stock market index in the United Kindgom, has given a return of 15 per cent during the same period. The Nikkei 225, the premier stock market index of Japan has rallied by 53 per cent during the same period. Closer to home, the BSE Sensex has rallied by around 43 per cent during the same period.”

Let’s take a closer look at the Indian stock market over the last two years. The foreign institutional investors have invested Rs 1,82,789.43 crore during this period (up to September 19,2014). During the same period the domestic institutional investors sold stocks worth Rs 1,07,327.65 crore.

It is clear from this that foreign money borrowed at low interest rates has been driving the Indian stock market. The domestic investors have continued to stay away.

So, even though a lot of domestic investors may talk about the India growth story being strong, they really don’t believe in it. If they did, they would invest money and not simply talk about it.

Hence, even though the economic growth through large parts of the world continues to remain subdued, the stock markets can’t seem to stop rallying. The explanation lies in the access to the “easy money” that the big institutional investors have.

And this access to easy money will continue in the days to come. The Bank of Japan, the Japanese central bank is printing around ¥5-trillion per month and is expected to do so till March 2015. The European Central Bank is also preparing to print €500-billion to €1-trillion over the next few years. All this money will be available for big institutional investors to borrow at very low interest rates.

The Federal Reserve of United States has made it clear that even though it will go slow on printing money in the days to come, it is unlikely to start pumping out all the money that it has put into the financial system any time soon.

Hence, the stock market bubbles around the world are likely to continue in the days to come. As Claudio Borio and Philip Lowe wrote in the BIS working paper titled Asset prices, financial and monetary stability: exploring the nexus “lowering rates or providing ample liquidity when problems materialise but not raising rates as imbalances build up, can be rather insidious in the longer run. They promote a form of moral hazard that can sow the seeds of instability and of costly fluctuations in the real economy.”

The worst, as they say, is yet to come.

The article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on Sep 27, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)