Over the last few years a spate of Ponzi schemes have come to light. These include Sahara, Saradha Chit Fund, Rose Valley Hotels and Entertainment and most recently PACL. A Ponzi scheme is essentially a fraudulent investment scheme in which money brought in by new investors is used to redeem the payment that is due to existing investors.

Over the last few years a spate of Ponzi schemes have come to light. These include Sahara, Saradha Chit Fund, Rose Valley Hotels and Entertainment and most recently PACL. A Ponzi scheme is essentially a fraudulent investment scheme in which money brought in by new investors is used to redeem the payment that is due to existing investors.

The instrument in which the money collected is invested appears to be a genuine investment opportunity but at the same time it is obscure enough, to prevent any scrutiny by the investors. So PACL invested the money it collected in agricultural land. Rose Valley, Sahara and Saradha had different businesses in which this money collected was invested.

These Ponzi schemes managed to raise thousands of crore over the years. In a recent order against PACL, the Securities and Exchange Board of India(Sebi) estimated that the company had managed to collect close to Rs 50,000 crore from investors. Sahara is in the process of returning more than Rs 20,000 crore that it had managed to collect from investors, over the years.

The question is how do these schemes manage to collect such a large amount of money. A June 2011, news-report in The Economic Times had estimated that PACL had managed to collect Rs 20,000 crore from investors at that point of time. This means that since then the company has managed to collect Rs 30,000 crore more from investors. An April 2013 report in the Mint quoting state officials had put the total amount of money collected by the Saradha at Rs 20,000 crore.

These Ponzi schemes have managed to collect a lot of money in an environment where the household financial savings in India have been falling. Household financial savings is essentially the money invested by individuals in fixed deposits, small savings scheme, mutual funds, shares, insurance etc.

The latest RBI annual report points out that “the household financial saving rate remained low during 2013-14, increasing only marginally to 7.2 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 from 7.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 and 7.0 per cent of GDP in 2011-12…the household financial saving rate [has] dipped sharply from 12 per cent in 2009-10.”

While the household financial savings have dipped, the money collected by Ponzi schemes has grown by leaps and bounds. What explains this dichotomy? Some experts have blamed the low penetration of banks as a reason behind the rapid spread of Ponzi schemes in the last few years. K C Chakrabarty, former deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, in September 2013 had pointed out that only 40,000 out of the 6 lakh villages in India have a bank branch.

Hence, investors find it easier to invest their money with Ponzi schemes, which seem to have a better geographical presence than banks. While this sounds logical enough, the trouble with this reasoning is that the bank penetration in India has always been low. It clearly isn’t a recent phenomenon. So, why have so many Ponzi schemes come to light only in the last few years?

Another reason offered is that the rate of return promised by these Ponzi schemes is high and is fixed at the time the investor enters the scheme. This is an essential characteristic of almost all Ponzi schemes. Take the case of Rose Valley. The return on the various investment schemes run by the company varied from anywhere between 11.2% to 17.65%.

In case of PACL The Economic Times report referred to earlier pointed out that “If a customer puts down Rs 50,000 for a 500 square yard plot, he or she can expect to get back Rs 1,01,365 in six years, or Rs 1.85 lakh in 10 years.” This meant a return of 12.5% and 14% on investments. An April 2013 report in the Business Standard pointed out that the fixed deposits of Saradha “promised to multiply the principal 1.5 times in two-and-a-half years, 2.5 times in 5 years and 4 times in 7 years.” This basically implied a return of 17.5-22%.

It is clear that returns promised by these Ponzi schemes have been significantly higher than the returns available on fixed income investments like fixed deposits, small savings schemes, provident funds etc., which ranged between 8-10%. Given this, it was the greed of the investors which drove them to these Ponzi schemes, and in the end they had to pay for it.

Again that would be a simplistic conclusion to draw. Rose Valley was paying 11.2% on one of its schemes. PACL was offering 12.5%. This returns weren’t very high in comparison to the returns on offer on other fixed income investments.

In fact, most Ponzi schemes tend to offer atrociously higher returns than this. Charles Ponzi on whom the scheme is named had offered to double investors’ money in 90 days. Or take the case of the Russian Ponzi scheme MMM, which came to India sometime back. Its sales pitch was that Rs 5000 could grow to Rs 3.4 crore in a period of twelve months. Speak Asia, a Ponzi scheme which made a huge splash across the Indian media a few years back, promised that an initial investment of Rs 11,000 would grow to Rs 52,000 at the end of an year. This meant a return of 373% in one year. Another Ponzi scheme Stock Guru, offered a return of 20% per month for a period of up to 6 months.

In comparison, the returns

offered by the likes of Rose Valley, Saradha, Sahara and PACL are very low indeed. But investors have still flocked to them. In fact, in its order against PACL, Sebi estimated that the company had close to 5.85 crore investors. So, the question is why are so many people investing money in such schemes?

The answer lies in the high inflation that has prevailed in the county since 2008. For most of this period the consumer price inflation and food inflation have been greater than 10%. In this scenario, the returns on offer on fixed income investments have been lower than the rate of inflation. Hence, people have had to look at other modes of investment, in order to protect the purchasing power of their accumulated wealth. A lot of this money found its way into real estate and gold. And some of it also found its way into Ponzi schemes. This is the “real” reason behind the explosion in the kind of money that has been raised by these Ponzi schemes.

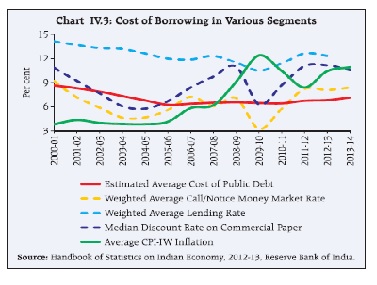

But why is the rate of interest on offer on fixed income investments been lower than the rate of inflation? This is where things get really interesting. Take a look at the graph that follows. The government of India since 2007-2008 has been able to raise money at a much lower rate of interest than the prevailing inflation. The red line which represent the estimated average cost of public debt(i.e. Interest paid on government borrowings) has been below the green line which represents the consumer price inflation, since around 2007-2008.

How has the government managed to do this? The answer lies in the fact that India is a financially repressed nation. Currently banks need to invest Rs 22 out of every Rs 100 they raise as deposits in government bonds. This number was at higher levels earlier and has constantly been brought down. Over and above this Indian provident funds like the employee provident fund, the coal mines provident fund, the general provident fund etc. are not allowed to invest in equity. Hence, all the money collected by these funds ends up being invested in government bonds.

As the Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework points out “Large government market borrowing has been supported by regulatory prescriptions under which most financial institutions in India, including banks, are statutorily required to invest a certain portion of their specified liabilities in government securities and/or maintain a statutory liquidity ratio (SLR).”

This ensures that there is huge demand for government bonds and the government can get away by offering a low rate of interest on its bonds. “The SLR prescription provides a captive market for government securities and helps to artificially suppress the cost of borrowing for the Government, dampening the transmission of interest rate changes across the term structure,” the Expert Committee report points out.

The rate of return on government bonds becomes the benchmark for all other kinds of loans and deposits. As can be seen from the graph above, the government has managed to raise loans at much lower than the rate of inflation since 2007-2008. And if the government can raise money at a rate of interest below the rate of inflation, banks can’t be far behind. Hence, the interest offered on fixed deposits by banks and other forms of fixed income investments has also been lower than the rate of inflation over the last few years.

This explains why so much money has founds its way into Ponzi schemes, even though the rate of return they have been offering is not very high in comparison to other forms of fixed income investment. To conclude, the government of India has had a significant role to play in the spread of Ponzi schemes.

A slightly different version of this article appeared on Quartz India on September 10, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of Easy Money: Evolution of the Global Financial System to the Great Bubble Burst. He can be reached at [email protected])