Many real estate companies around the National Capital Region have taken money from homebuyers over the years, and failed to deliver homes. Some of these companies have also defaulted on bank loans.

Take the case of Jaypee Infratech, one such company, which has been in the news lately. The company has collected anywhere from 70 to 100 per cent of the price of the homes that they were selling, from around 27,000 buyers. These buyers have paid anywhere between Rs 40 lakh each to Rs 1 crore each, to the company.

On the other hand, the company has defaulted on a loan of Rs 526 crore.

Or let’s take the case of Amrapali Group. One of the group companies (Amrapali Silicon City Private Ltd.) has defaulted on a loan amount of Rs 59.38 crore. Over and above this defaulted amount, overdue interest and penal interest adds to another Rs 11.77 crore.

This takes the total amount to a little over Rs 71 crore. On the other hand, a newsreport in The Times of India suggests that there are nearly 45,000 homebuyers to whom the Amrapali group hasn’t delivered the promised homes.

A report in the Business Today suggests that the group “owes over Rs 1,000 crore to about 10 banks”.

When a debtor defaults, the banks can file an application under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, with the National Company Law Tribunal, to trigger the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process and appoint an insolvency resolution professional.

Under this, the existing board of the company is suspended. The professional has 180 days to come up with a workable solution for the company to be able to repay the loans it has defaulted on. This can be extended by another 90 days. At the end of 270 days if no solution is in sight, then a liquidator is appointed.

The trouble is that currently the homebuyers are not on the list of entities that will be compensated for payment of what is due to them once the company is liquidated. Some suggestions have been made that the homebuyers can be compensated under Section 53(1)(f) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. This is after workmen, secured creditors, employees other than workmen, unsecured creditors, amounts owed to the central and the state government, etc., have been compensated and before preference shareholders and equity shareholders, are compensated.

In fact, Section 53(1)(f) lists “any remaining debts and dues,” under it. The question is can the money handed over by the homebuyers to these real estate companies be treated as debt? From the legal point of view this does not make sense given that the money that the buyers had handed over to the real estate companies was basically an advance and not a loan. Even with this point, the homebuyers come to low in the hierarchy to hope to be compensated at the end of the liquidation process.

In the case of Jaypee Infratech, where the buyers went to the Supreme Court, in order to stall the insolvency resolution process, the Court has directed the insolvency resolution professional to come up with an interim resolution plan within 45 days. This plan is expected to take into account the interests of homebuyers i.e. those people who paid Jaypee Infratech for homes that were never delivered.

The Supreme Court needs to basically decide whether homebuyers can be categorised as financial creditors or not.

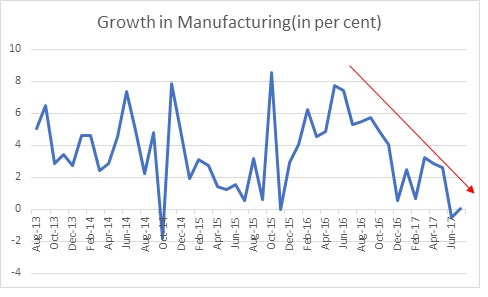

But does not answer the basic question: Where did the money that the homebuyers handed over to the real estate companies, actually go? This is an important question to ask because the bank loans that the developers have defaulted on are really very small, in comparison to the total amount of money they have raised from homebuyers and siphoned off.

Take the case of Jaypee Infratech. The company has defaulted on a Rs 526 crore loan from IDBI Bank. In comparison, various media reports and suffering homebuyers suggest, that the company has taken on more than Rs 20,000 crore from homebuyers. Where did this money go?

Given this, the bank defaults and the non-delivery of homes are two separate issues, and they need to be treated separately.

Of course, Jaypee Infratech is not the only company here. There are many other companies. A newsreport in The Hindustan Times suggests that 13 FIRs were filed against six such companies, Amrapali, Supertech, Alpine Realtech Private Limited, BRUY Limited, Today Home Builders and JNC developers, in early September 2017.

The question is where did the money all these companies and others, raised from homebuyers disappear? Did the promoters pad up the expenses and tunnel this money out to buy land? Or did they simply siphon this money off? Or did they use it to complete other projects? And if that was the case, where did the money that was raised for these other projects go? It clearly seems that money has been laundered by promoters of these companies.

Unless, these questions are answered and the homebuyers’ money recovered from the errant real estate companies, there is no way that this issue can be solved.

Hence, the questions listed above need to be investigated. Given that FIRs have already been filed against many real estate companies which have not delivered on homes, under the required sections of the Indian Penal Code, the Enforcement Directorate can register cases against these companies and carry out detailed investigations under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA).

Of course, this would mean investigating many companies, but the modus operandi of laundering money in many cases would be similar. At the same time, this can set the record straight for the future. If housing for all is to be achieved by 2022 (or even 2032 for that matter), the private real estate companies need to play an important role in it. And given that, it is important that the errant real estate companies not be allowed to get-away with the crime that they have committed against the homebuyers.

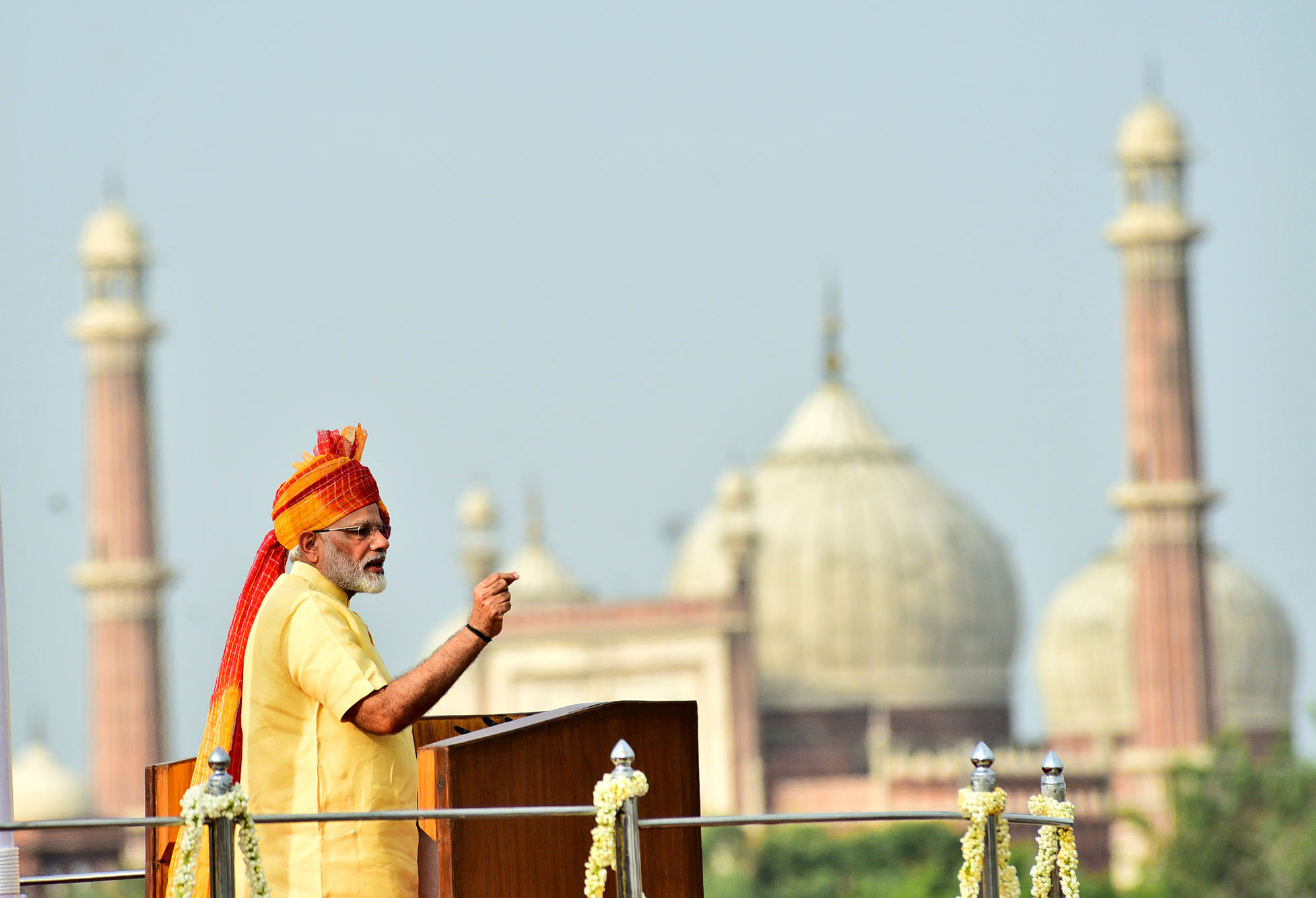

A precedent needs to be set, so that in the future, things like these do not happen all over again. It is also an excellent opportunity for prime minister Narendra Modi to revive his fight against black money and show some concrete action on this front. The hard-earned money of most homebuyers has been laundered and converted into black money and that needs to be tackled.

The column originally appeared on Equitymaster on September 18, 2017.