The index of industrial production (IIP) figures declared earlier this week, portray a worrying picture of the overall Indian economy. The IIP is a measure of industrial activity in the country.

For the month of July 2017, the IIP grew by 1.2 per cent in comparison to July 2016. In June 2017, it had contracted by 0.2 per cent. While, there has been some improvement month on month, the overall trend of the IIP growth has been down for a while. Take a look at Figure 1, which basically plots the IIP growth (or contraction for that matter) over the last four years.

Figure 1:

As is clear from Figure 1, for more than a year now, the overall trend of IIP growth in the country has been downward. This is a clear indication of a slowdown in the growth of industrial activity.

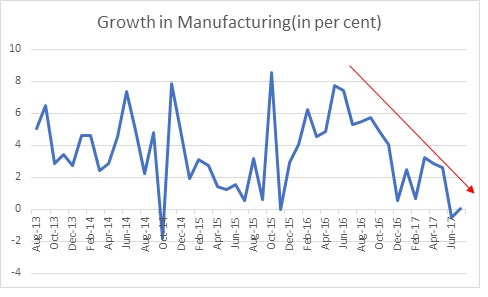

One of the ways through which IIP is measured is referred as economic activity based classification. As per this method, manufacturing accounts for 77.6 per cent of the IIP. And if things for overall IIP have been bad, they have been worse for manufacturing. Take a look at Figure 2, which basically plots the growth (and contraction) in manufacturing over the last four years.

Figure 2:

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

What does Figure 2 tell us? The manufacturing scene in the country doesn’t look great. In July 2017, manufacturing grew by just 0.1 per cent, after having contracted by 0.5 per cent in June 2017. This is a trend that was also visible in the gross domestic product (GDP) data released in late August 2017. Let’s take a look at Figure 3, which plots the growth rates of industry and manufacturing using GDP data, over the last four years.

Figure 3:

Figure 3 clearly tells us that the growth in industry and manufacturing as per the GDP data is at a four-year low. For the period April to June 2017, industry and manufacturing grew at 1.6 per cent and 1.2 per respectively, in comparison to the same period last year.

What does this mean for the overall economy? Industry has formed around 29-31 per cent of the GDP over the years. The fact nearly one-third of the economy is barely growing should be a big reason for worry. This will impact economic growth in both direct and indirect ways. If one-third of the economy barely grows, overall economic growth is bound to slowdown. That is the direct impact.

What about the indirect impact? In order to understand this, we need to figure out how many people actually work for industry. In 2009-2010, the industry as a whole employed around 9.9 crore individuals. Analysts, Nikhil Gupta and Madhurima Chowdhury, who work for stock brokerage Motillal Oswal, in a recent research note using data from the 2014-2015 Annual Survey of Industries, state: “Over the past 35 years, employment in Indian industrial sector has grown at an average of ~2%.” The actual figure is 1.9 per cent per year.

Hence, employment in the industrial sector tends to rise at the rate of 1.9 per year on an average. Using this, we can conclude that by March 2017, the total number of people working in industry would stand at around 11.3 crore. Further, the average Indian family has 5 people. Given this, around 55 crore individuals in a population of 130 crore or around 42 per cent of the population depend on income from industry, in one way or another. An if the industry is barely growing, these people will go slow on their consumption and other expenditure, and in the process slowdown overall economic growth. This is the indirect impact.

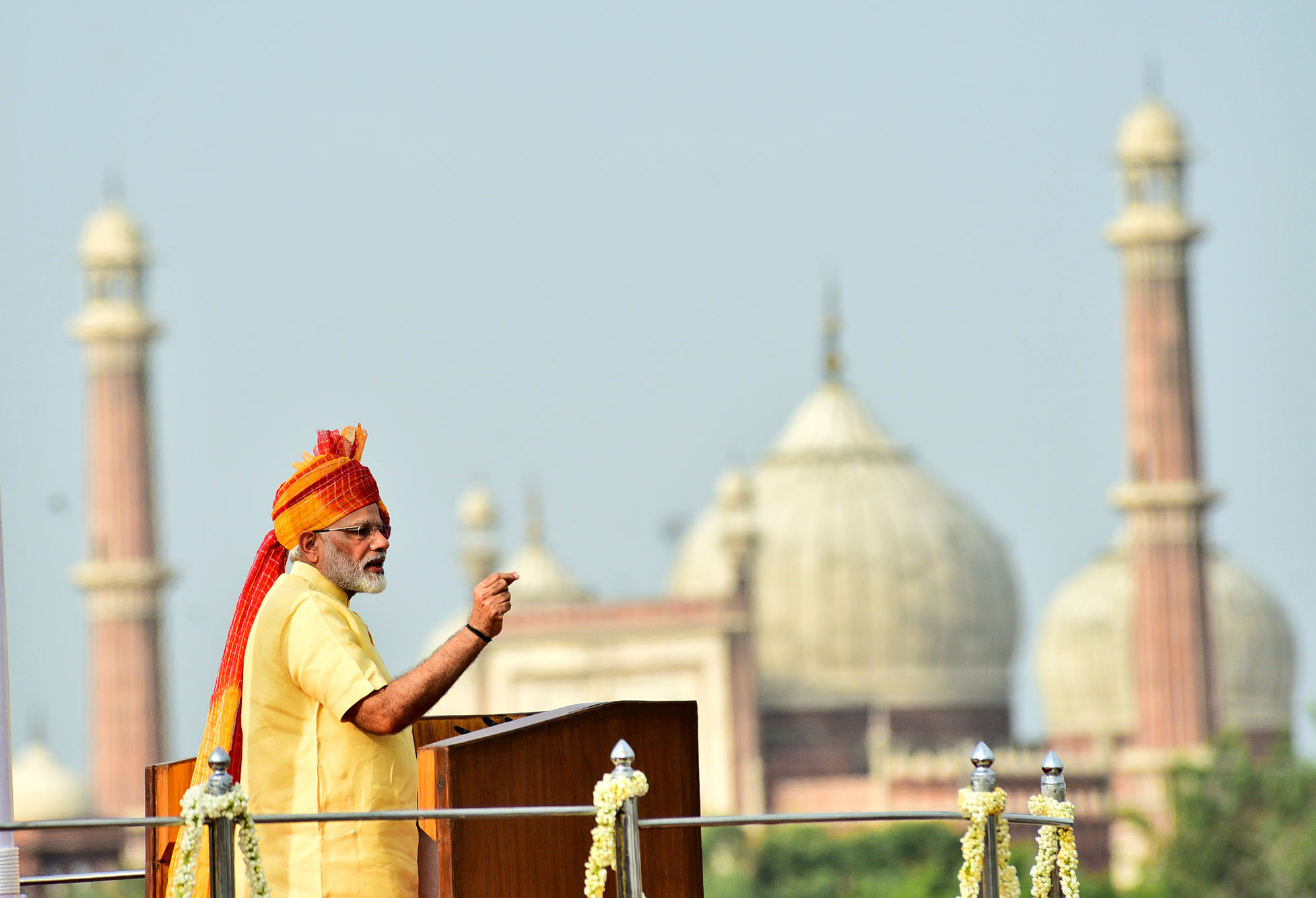

Why is this happening? The economic slowdown initiated by demonetisation is basically continuing. It is worth remembering that first and foremost is a medium of exchange. It is a token to carry out economic transactions. When you take 86.4 per cent of the currency in circulation out of an economy, where 80 to 98 per cent of the consumer transactions (in volume, and depending on which data source you take) is carried out in cash, economic transactions are bound to slowdown. And ultimately this is reflecting in the manufacturing data.

If there is slowdown in consumption, there is a bound to be a slowdown in manufacturing. If people are not buying stuff at the same pace as they were in the past, there is no point in companies increasing production like they were in the past.

The irony is that this crisis the Modi government brought upon us. Indeed, this is very worrying in a country where one million individuals are entering the workforce every month. That makes it 1.2 crore, a year. If the growth in industrial sector slows down to the level that it currently has, how will any jobs be created for these youth.

And that is a question worth asking.

The column originally appeared in Newslaundry on September 14, 2017.