Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Federal Reserve of the United States, the American central bank, has been rapidly expanding its balance sheet since late 2008. As on November 13, 2013, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet was at $3.907 trillion.

Now compare this to the size of the Fed’s balance sheet as on September 10, 2008, when it stood at around $940 billion. The investment bank Lehman Brothers went bust as on September 15, 2008, which led to the start of the current financial crisis.

Since late 2008, the Federal Reserve has been printing dollars. It has been pumping these dollars into the financial system by buying financial securities like American government bonds and mortgage backed securities. Currently, the Fed buys $85 billion worth of financial securities every month.

The securities that the Federal Reserve buys are reflected as assets on its balance sheet. Hence, the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve has increased in size by a whopping 316% in a little over five years. In fact, the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve should touch the size of $4 trillion sometime next month, given that it continues to print dollars and buy financial securities worth $85 billion every month.

At $4 trillion, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet will be nearly 25.5% of the US gross domestic product of $15.68 trillion in 2012. In fact, if the Federal Reserve continues to print money at the rate it is currently, its balance sheet will cross $5 trillion in a year’s time. These are fairly big numbers that we are talking about.

The idea behind printing money was to ensure that there was enough money going around in the financial system and hence, the interest rates continued to stay low. At low interest rates people were more likely to borrow and spend, and this would help revive business growth and in turn economic growth.

But that hasn’t turned out to be the case and economic growth continues to remain low in United States and much of the Western world. Also, the prevailing belief seems to be that demand can be created by keeping interest rates low for a long period of time.

As investment newsletter writer and hedge fund manager John Mauldin writes in his latest report The Unintended Consequences of ZIRP released on November 16, 2013 “The belief is that it is demand that is the issue and that lower rates will stimulate increased demand (consumption), presumably by making loans cheaper for businesses and consumers. More leverage is needed! Butcurrent policy apparently fails to grasp that the problem is not the lack of consumption: it is thelack of income.”

People borrow and spend money when they feel confident about the future. Right now, they just don’t. A major reason for this is the fact that United States and large parts of Europe are in the midst of what Japanese economist Richard Koo calls a balance sheet recession.

In a balance sheet recession a large portion of the private sector, which includes both individuals and businesses minimise their debt. When a bubble that has been financed by raising more and more debt collapses, the asset prices collapse but the liabilities do not change.

In the American context what this means is that people had taken on huge loans to buy homes in the hope that prices would continue to go up for perpetuity. But that was not to be. Once the bubble burst, the housing prices crashed.

This meant that the asset (i.e. homes) that people had bought by taking on loans, lost value, but the value of the loans continued to remain the same. Hence, people needed to repair their individual balance sheets by increasing savings and paying down debt. This act of deleveraging or reducing debt has brought down aggregate demand and has thrown the economy in a balance sheet recession.

Koo feels this is what has been happening in the United States where people have been paying down their debts, by increasing their savings. In mid 2005, when the housing bubble was at its peak, an average American was saving around 2% of his or her personal disposable income. This has since jumped to nearly 5%. In this scenario, it is unlikely that many people would want to borrow more, even if interest rates continue to remain low.

Individuals may not be borrowing as much as the American government expected them to, institutional investors have more than made up for it. Borrowing dollars at close to zero percent interest rates, they have invested money in financial markets all over the world. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, America’s premier stock market index, crossed a level of 16,000 points for the first time yesterday. The BSE Sensex also continues to trade close to 21,000 points, despite the Indian economy being in a bad shape.

Since the beginning of this year, the foreign institutional investors have invested Rs 71, 308.51 crore, in the Indian stock market. This is a clear impact of the easy money policy being run by the Federal Reserve. During the same period the domestic institutional investors have sold stocks worth Rs 62,573.45 crore. These are clear signs of the stock market being in the midst of a bubble.

The Federal Reserve can keep printing as many dollars as it wants to, given that there is no theoretical limit to it. Also, money printing is not having the kind of impact it was expected to have to create economic growth. At the same time it has led to financial market bubbles all over the world.

As Mauldin puts it “they also know they cannot continue buying $85 billion of assets every month. Their balance sheet is already at $4 trillion and at the current pace will expand by $1 trillion a year. Although I can find no research that establishes a theoretical limit, I do believe the Fed does not want to find that limit by running into a wall. Further, it now appears that they recognize that QE(quantitative easing or the fancy name economists have given to the Federal Reserve printing money) is of limited effectiveness.”

The trouble is that if the Federal Reserve decides to go slow on money printing, there will be a sell off across financial markets all over the world. And that will have fairly negative consequences for the US and large parts of the world.

Also, the Federal Reserve has more or less run out of the tools that it has at its disposal to revive the American economy. As Ray Dalio of Bridgewater pointed out in a recent note. “The dilemma the Fed faces now is that the tools currently at its disposal are pretty much used up, in that interest rates are at zero and US asset prices have been driven up to levels that imply very low levels of returns relative to the risk, so there is very little ability to stimulate from here if needed. So the Fedwill either need to accept that outcome, or come up with new ideas to stimulate conditions,” writes Dalio.

The Federal Reserve is in a catch 22 situation right now. Should it continue to print money? Should it go slow? This is a question that Janet Yellen, the Federal Reserve Chairman in waiting, needs to answer.

The article first appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 19, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Month: November 2013

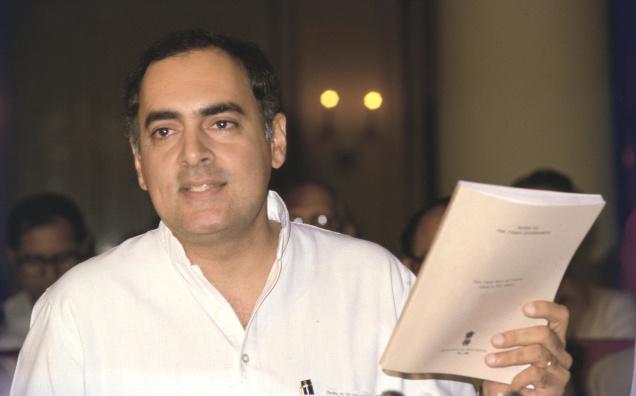

Note to Rahul: India sucks at producing rakhis and Ganeshas

Vivek Kaul

Economist Arvind Panagariya has written an open letter to Rahul Gandhi, on the edit page of today’s edition of The Times of India. In this piece Panagariya answers Gandhi’s query to Indian industrialists, as to why India has to import ganeshas and rakhis from China and can’t produce them on its own.

Panagariya’s answer is very simple. India sucks at labour intensive manufacturing. As he writes “our top industry leaders are very comfortable doing what they do: invest in highly capital-intensive sectors such as automobiles, auto parts, two wheelers, engineering goods and chemicals or in skilled-labour-intensive goods such as software, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals and finance. The vast labour force of the nation stares them in the face but they look the other way.”

This is the major reason as to why India cannot compete with China in manufacturing rakhis and ganeshas. But some historical context also needs to be built in, in order to completely appreciate India’s lack of competitiveness on this front.

Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis founded the Indian Statistical Institute in two rooms at the Presidency College in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the early 1930s. He became close to Jawahar Lal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, and was appointed as the Honorary Statistical Advisor to the government of India.

As Gurcharan Das writes in India Unbound –From Independence to the Global Information Age “Mahalanobis had a profound effect on Nehru’s thinking, although he held no offcial position. His title, “Honorary Statistical Advisor to the Government of India,” certainly did not reflect the extent of his influence. His biggest contribution was the draft plan frame for the Second Five Year Plan…In it he put into practice the socialist ideas of investment in a large public sector (at the expense of the private sector), with emphasis on heavy industry (at the expense of consumer goods) and a focus on import substitution(at the expense of export promotion).”

Hence, big heavy industry became the order of the day at the cost of small consumer goods. The alternative vision of encouraging the production of consumer goods was put forward as well. As Das writes “It belonged to the Bombay (now Mumbai) economists CN Vakil and PR Brahmanand. It was neither glamourous nor as technically rigorous as Mahalnobis’s, but it was more suited to the underdeveloped Indian economy. Its starting point was that India lacked capital but had plenty of people…The thing to do was to put these people into productive work at the lowest capital cost. The Bombay economists suggested that we employ the surplus labour to produce “wage goods,” or simple consumer products – clothes, toys, shoes, snacks, radios, and bicycles. These low-capital, low-risk, business would attract loads of entreprenurs, for they would yield quick output and rapid returns on investments. Labour would produce the goods it would eventually consume with the wages it earned in producing the goods.”

But Mahalanobis’s vision of an industrialisted India sounded a lot sexier to the politicians led by Nehru who ran this country and hence, won in the end.

The Indian industrialists had done their cause no good by drafting and accepting the Bombay Plan in 1944. “In 1944, India’s leading capitalists had come together in Bombay and crystalllized their vision for a modern, independent India. They inclued the giants of Indian business – JRD Tata, GD Birla, Lala Shri Ram, Kasturbhai Lallabhai, Purshotamdas Thakurdas, AD Shroff and John Mathai – they produced what came to be known as the Bombay Plan,” writes Das.

The Bombay Plan put forward the idea of rapid and self reliant industrialisation of business in India. At the same time the businesses were willing to accept “import limitations on the freedom of private enterprise”. “Even more disastrous was their acceptance of a vast area of state control – in fixing prices, limiting dividends, controlling foregin trade and foreign exchange, in licensing production, and in allocating capital goods and distributing consumer goods. Without realising it, the Indian capitalists had dug their graves,” writes Das.

Hence, the government became the mai baap sarkar which gave out licenses for everything. And the Indian businessman if he had to survive had to become a crony capitalist to get these licenses. This was initiated during the regime of Jawahar Lal Nehru and perfected during the rule of his daughter Indira Gandhi.

The orientation of the Indian government was towards setting up big industries. What they did not want to set up themselves, they would give licenses to the private sector. And in order to get licenses a businessman had to be close to the government.

This ensured that both the government as well as the private sector set up and continue to set up capital intensive businesses. This is reflected in the slow growth of the number of workers working in private sector etablishemnts with ten or more people. As Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya write in their book India’s Tryst with Destiny – Debunking Myths that Undermine Progress and Addressing New Challenges. “The number of workers in all private-sector establishments with ten or more workers rose from 7.7 million in 1990-91 to just 9.8 million in 2007-2008. Employment in private- sector manufacturing establishments of ten workers or more, however, rose from 4.5 million to only 5 million over the same period. This small change has taken place against the backdrop of a much larger number of more than 10 million workers joining the workforce every year.”

Hence, an average Indian business starts off small and continues to want to remain small. “An astonishing 84 per cent of the workers in all manufacturing in India were employed in firms with forty-nine or less workers in 2005. Large firms, defined as those employing 200 or more workers, accounted for only 10.5 percent of manufacturing workforce. In contrast, small- and large-scale firms employed 25 and 52 per cent of the workers respectively in China in the same year,” write Bhagwati and Panagariya.

What is true about manufacturing as a whole is also true about apparels in particular, a very high labour intensive sector. Nearly 92.4% of the workers in this sector, work with small firms which have 49 or less workers. In comparison, large and medium firms make up around 87.7% of the employment in the apparel sector in China.

The labour intensive firms in China ensure that they have huge economies of scale. This drives down costs and explains to a large extent why India imports ganesha idols and rakhis from China. Everyone wants a good deal. And China is the country providing the good deals and not India.

A major reason for Indian firms choosing to remain small is the fact that the country has too many labour laws. Since labour is under the Concurrent list of the Indian constitution, both the state government as well as the central government can formulate laws on it. As Bhagwati and Panagariya point out “The ministry of labour lists as many as fifty-two independent Central government Acts in the area of labour. According to Amit Mitra(the finance minister of West Bengal and a former business lobbyist), there exist another 150 state-level laws in India. This count places the total number of labour laws in India at approximately 200. Compounding the confusion created by this multitude of laws is the fact that they are not entirely consistent with one another, leading a wit to remark that you cannot implement Indian labour laws 100 per cent without violating 20 per cent of them.”

This explains to a large extent why Indian businesses do not like to become labour intensive and choose to stay small. The costs of following these laws are huge. As Bhagwati and Panagariya write “As the firm size rises from six regular workers towards 100, at no point between these two thresholds is the saving in manufacturing costs sufficiently large to pay for the extra cost of satisfying the laws.”

In fact, Bhagwati and Panagariya narrate an interesting anecdote told to them by economist Ajay Shah. Shah, it seems asked a leading Indian industrialist about why he did not enter the apparel sector, given that he was already making yarn and cloth. “The industrialist replied that with the low profit margins in apparel, this would be worth while only if he operated on the scale of 100,000 workers. But this would not be practical in view of India’s restrictive labour laws.”

This is the answer to Rahul Gandhi’s question of why India imports rakhis and ganeshas from China. Like is the case with almost every big problem in this country, even this is a problem created by his ancestors.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 18, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Is Eurozone trying to become a bigger Germany?

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

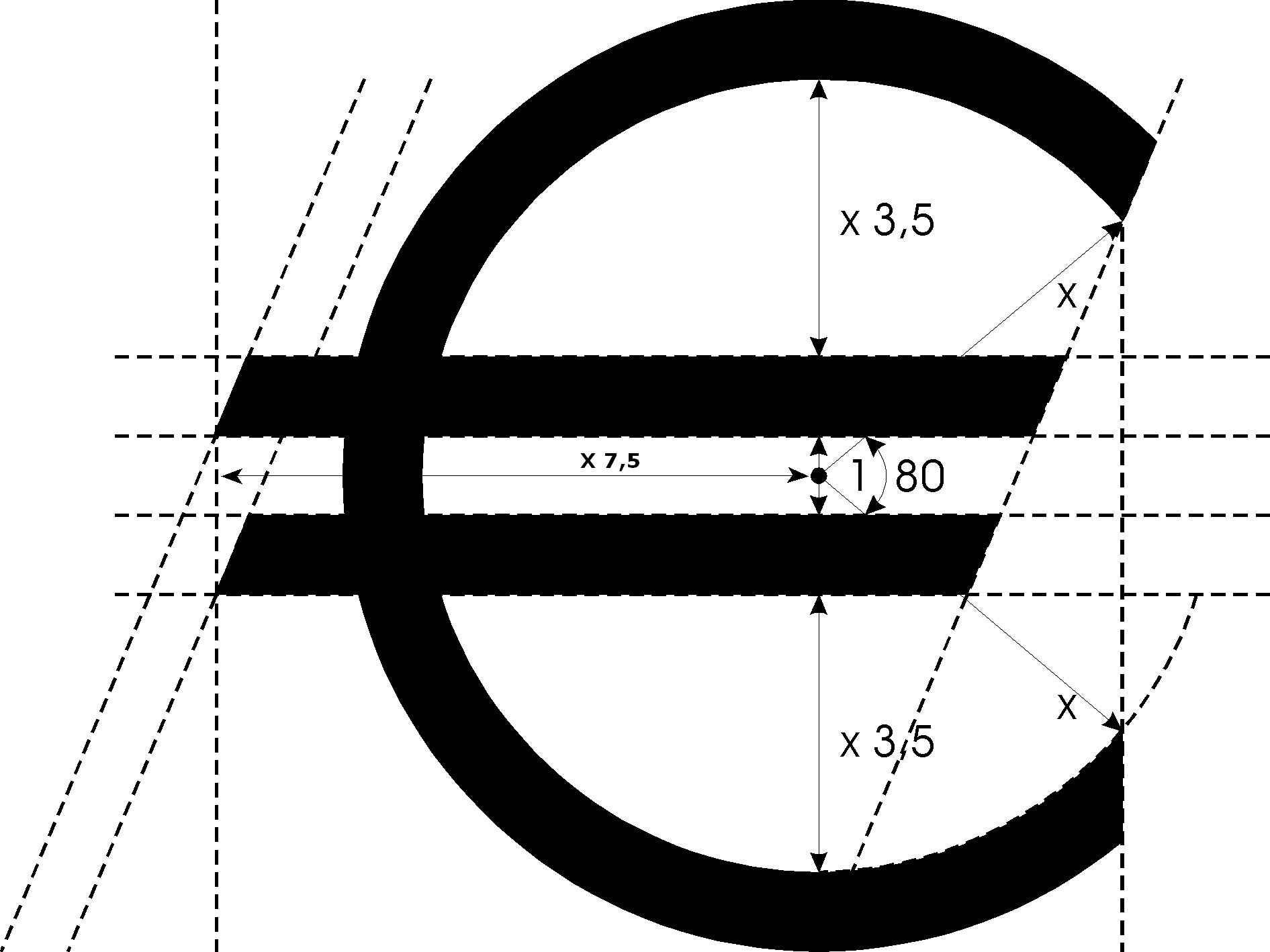

The US Department of Treasury publishes a semi-annual currency report. The latest report released on October 30, 2013, makes a scathing attack at Germany. “Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany’s nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany’s anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro-area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy,” the report points out.

So what does this mean in simple English? Germany has been the export powerhouse of the world. It exports considerably more than it imports. This is the formula it has been trying to force onto other countries of the Eurozone as well. Eurozone is a term used for 17 countries which have adopted euro as their currency.

Some of these countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland etc have not been in the best economic condition over the last few years, with a huge amount of private as well as government debt. This was a result of going overboard with their spending in the years before the financial crisis started.

As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writes in a report titled Prepare for the next phase of global currency war – should we blame Germany? dated November 14, 2013, “In the run-up tothe crisis they all promoted an inappropriately loose monetary policy that caused a credit and housing bubble, runaway domestic demand growth, ostensibly sound government finances and burgeoning current account deficits, all financed by a surplus nation…predominately Germany.”

Countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland etc went on a borrowing spree, which ultimately led to a housing bubble. When the bubble burst the banking system in these countries was in a mess. They had to be bailed out by the European Central Bank(ECB). At the same time countries were forced to follow austerity measures to control government expenditure. These measures have led to an extremely high level of unemployment in these countries. As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Daily Telegraph pointed out in a recent column “unemployment is 27.8% in Greece, 26.3% in Spain, 17.3% in Cyprus, and 16.5% in Portugal.. it would be far worse had it not been for a mass exodus of EMU refugees….Greek youth unemployment is 62.9%.”

This has led to a situation where internal demand in these countries fell dramatically. A fall in internal demand has meant lower imports. And this in turn has led to exports being greater than imports, and hence a trade surplus( a situation where exports of a country are greater than its imports). The eurozone trade surplus in August 2013 was at $9.5 billion.

Interestingly, the collapse of demand within these countries has also led to a situation where German exports within the Eurozone have fallen. “It is that actually Germany’s trade surplus within the Eurozone has collapsed to almost zero as the GIIPS(Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain)have plunged into depression,” writes Edwards.

This basically means that Germany is importing as much from other countries in the Eurozone as it is exporting to them, leading to a trade surplus of almost zero. But it has more than made up for this by running a higher trade surplus with other parts of the world, primarily United States and large parts of Asia.

Hence, it isn’t surprising that the United States has a problem with Germany. While Germany is exporting goods and services to the United States, it isn’t importing the same amount back from the United States or other parts of the world for that matter. This means that businesses in the United States and other parts of the world are not exporting enough, which in turn has an impact on economic growth.

This formula of running a trade surplus by exporting more and limiting imports has worked very well for Germany. But the question is will it work for the Euro Zone as a whole? Martin Wolf of The Financial Times feels that the strategy may not work for two reasons. “First, the eurozone is far too big to achieve export-led growth, as Germany has done; and, second, the currency is likely to appreciate still further, thereby squeezing the less competitive economies all over again.”

The euro is likely to appreciate in the days to come given that both Japan and United States are printing money big time in the hope of devaluing their currencies. Also, this formula will have political complications as well, given that, exports can only happen if someone else is importing. Every country cannot be an exporter at the same time. Someone has to import as well.

And who will that importer be? Sanjeev Sanyal of Deutsche Bank writes in a report titled Bretton Woods III and the Global Savings Glut dated October 8, 2013 “Reinterpreted to present conditions, the next round of global economic expansion may require the US to revert to its role as the ultimate sink of global demand.”

Or as the French like to put it plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.(the more things change, the more they stay the same).

The article was originally published on www.firstpost.com on November 15, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

If only Raghuram Rajan could control onion prices too

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

On November 12, the rupee touched 63.70 to a dollar. On November 13, Raghuram Rajan, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) decided to address a press conference. “There has been some turmoil in currency markets in the last few days, but I have no doubt that volatility may come down,” Rajan told newspersons.

Rajan was essentially trying to talk up the market and was successful at it. As I write this, the rupee is quoting at at 63.2 to a dollar. The stock market also reacted positively with the BSE Sensex going up to 20,568.99 points during the course of trading today (i.e. November 14, 2013), up by 374.6 points from yesterday’s close.

But the party did not last long. The wholesale price inflation (WPI) for October 2013 came in at 7%, the highest in this financial year. In September 2013 it was at 6.46%. In August 2013, the WPI was at 6.1%, but has been revised to 7%. The September inflation number is also expected to be revised to a higher number. The stock market promptly fell from the day’s high.

A major reason for the high WPI number is the massive rise in food prices. Overall food prices rose by 18.19% in October 2013, in comparison to the same period last year. Vegetable prices rose by 78.38%, whereas onion prices rose by 278.21%.

Controlling inflation is high on Rajan’s agenda. “Food inflation is still worryingly high,” he had told the press yesterday. In late October, while announcing the second quarter review of the monetary policy Rajan had said “With the more recent upturn of inflation and with inflation expectations remaining elevated… it is important to break the spiral of rising price pressures.”

If Rajan has to control inflation, food inflation needs to be reined in. The trouble is that there is very little that the RBI can do in order to control food inflation.

A lot of vegetable growing is concentrated in a few states. As Neelkanth Mishra and Ravi Shankar of Credit Suisse write in a report titled Agri 101: Fruits & vegetables—Cost inflation dated October 7, 2013, “While the Top 10 vegetable producing states contribute 78% of national production, the contribution of West Bengal, Orissa and Bihar is much higher than their contribution to overall GDP. For example, despite being just 2.7% of India’s land area and 7.5% of population, West Bengal produces 19% of India’s vegetables, dominating the production of potatoes, cauliflowers, aubergines and cabbage. In fact, for almost each crop, the four largest states are 60% or more of overall . In particular, Maharashtra dominates the onion trade (45% of national production by value), while West Bengal produces 38% of India’s potatoes, 49% of India’s cauliflower and 27% of India’s aubergines (brinjal). ”

The same stands true for fruits as well. As the Credit Suisse analysts point out “Maharashtra (MH) dominates citrus fruits (primarily oranges), Tamil Nadu (TN) produces nearly 40% of India’s bananas, Andhra Pradesh (AP) is Top 3 in all the three major fruits, and Uttar Pradesh (UP) produces a fifth of India’s mangoes.”

Hence, the production of vegetables as well as fruits is geographically concentrated. What this means is that if there is any disruption in supply, there is not much that can be done to stop prices from goring up. Given the fact that the production is geographically concentrated, hoarding is also easier. Hence, it is possible for traders of one area to get together, create a cartel and hoard, which is what is happening with onions. (As I argue here). There is nothing that the RBI can do about this. What has also not helped is the fact that the demand for vegetables has grown faster than supply. As Mishra and Shankar write “Supply did respond, as onion and tomato outputs grew the most. But demand rose faster, with prices supported by rising costs.” Hence, even if food inflation moderates, there is very little chance of it falling sharply, feel the analysts.

This is something that Sonal Varma of Nomura Securities agrees with. As she writes in a note dated November 12, 2013 “On inflation, vegetable prices have not corrected as yet and the price spike that started with onions has now spread to other vegetables. Hence, CPI (consumer price inflation) will likely remain in double-digits over the next two months as well.” The consumer price inflation for the month of October was declared a couple of days back and it was at 10.09%.

Half of the expenditure of an average household in India is on food. In case of the poor it is 60% (NSSO 2011). The rise in food prices over the last few years, and the high consumer price inflation, has firmly led people to believe that prices will continue to rise in the days to come. Or as economists put it the inflationary expectations have become firmly anchored. And this is not good for the overall economy.

As Varma puts it “For a sustainable decline in inflation to pre-2008 levels, the vicious link between high food price inflation and elevated inflation expectations has to be broken. The persistence of retail price inflation near double-digits for over five years has firmly anchored inflationary expectations at an elevated level. The role of monetary policy in tackling food price inflation is debateable.”

What she is saying in simple English is that there not much the RBI can do to control food inflation. It can keep raising interest rates but that is unlikely to have much impact on food and vegetable prices.

Varma of Nomura, as well as Mishra and Shankar of Credit Suisse expect food inflation to moderate in the months to come. But even with that inflation will continue to remain high.

As Varma put it in a note released on November 14, “Looking ahead, we expect vegetable prices to further moderate from December, which should lower food inflation. However, this is likely to be offset by other factors. Domestic fuel prices remain suppressed and the release of this suppressed inflation (especially in diesel) will continue to drive fuel prices higher. Also, manufacturer margins remain under pressure and hence the risk of further pass-through of higher input prices to output prices, i.e., higher core WPI inflation, is likely.”

What this means is that increasing fuel prices will lead to higher inflation. Also, as margins of companies come under threat, due to high inflation, they are likely to increases prices, and thus create further inflation.

All this impacts economic growth primarily because in a high inflationary scenario, people have been cutting down on expenditure on non essential items like consumer durables, cars etc, in order to ensure that they have enough money in their pockets to pay for food and other essentials. And people not spending money is bad for economic growth.

If India has to get back to high economic growth, inflation needs to be reined in. As Rajan wrote in the 2008 Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms “The RBI can best serve the cause of growth by focusing on controlling inflation.” The trouble is that there is not much that the RBI can do about it right now.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 14, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Inflation over 10%: India needs a Rajiv Gandhi Inflation Control Yojana

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

“But Ma I want to become an economist,” said the son.

“An economist?” asked the mother. “Why in the world do you want to do that? You are already a politician.”

“Aren’t they kind of cool?” asked the son.

“Care to explain?”

“Look at Rajan at the Reserve Bank, the women are just swooning over him,” said the son. “Mrs De even wrote a column on how hot he is.”

“Yes. But do you remember the one before Rajan? No woman would have fallen for him, even though he did try and learn the salsa dance,” said the mother, puncturing the bubble.

“Ah, trust you to spoil the fun as always,” said the son. “I was so looking forward to the women swooning over me.”

“Aren’t they already,” replied the mother, trying to do some damage control. “Look at the number of responses we have got to that advertisement we placed on globalshadi.com. Wanted a fair, convent educated, homely girl who respects her elders and can cook.”

“He He.”

“But why do you suddenly want to become an economist?”

“Oh, every other day the media talks about inflation, index of industrial production and what not,” said the son. “And I don’t understand any of it.”

“But you don’t have to understand all that beta,” said the mother. “What else do we have mauni baba for?”

“Oh yeah, mauni baba is an economist, I had almost forgotten, given that he rarely speaks these days.”

“Yes. Let me just call him for you.”

Five minutes later, mauni baba is hurried in through the door.

“What happened madam?” he asked. “Hope all is well.”

“Nothing really,” she replied. “My son here just had a few small doubts. I’ll leave the two of you alone to have a man to man talk.”

Saying this, the mother left the room and the son decided to brush up on his economics.

“You know sir, the index of industrial production(IIP) number came in earlier in the day and it rose by 2%.”

“Yes, it did beta. What do you want to know about it?” asked mauni baba rather lovingly.

“Why is the number so low?”

“We are going through tough times. You know the IIP essentially measures the level of the industrial activity in the country.”

“But isn’t 2% very low?”

“Yes it is. In fact, if we look at just manufacturing which forms 75% of the IIP, it grew by only 0.6%.”

“Oh, so low?”

“Yes,” said mauni baba. “The industrial activity in the country has come to a standstill.”

“But why is that?” asked the son.

“People are not buying as many cars as they were. Neither are they buying consumer durables, which fell by 10% during September 2013, in comparison to the same period last year,” said mauni baba, without answering the question.

“But what is the problem?”

“The problem is inflation. The consumer price inflation for the month of October 2013 was at 10.09%.”

“Oh, yes I saw that on television,” said the son. “They keep going on and on about onion and tomato prices going up. I am so bored of watching that.”

“Yes, you should watch Star World Premiere HD.”

“And if they can’t eat onions and tomatoes, why don’t they try pasta and pizza,” said the son. “Or even caviar.”

“Doesn’t go down well with the Indian taste, you know,” said mauni baba. “We need our dal, rice and rasam.”

“So you were telling me something about inflation.”

“Yes. So inflation is greater than 10%. Food inflation is higher. Consumer price inflation number suggests that food inflation is at 12.56%. As per the wholesale price inflation number, the food inflation is at 18.4%.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Half of the expenditure of an average Indian household goes towards food. Given the rate at which food prices are rising, more and more money is being spent on paying for food and other essentials.”

“Oh.”

“Hence, there is very little money left to buy non essential items like consumer durables and cars. And this leads to low industrial activity. When the demand falls, so does the supply.”

“But where does this inflation come from?” asked the son. “Why can’t we just stop it by launching a RGICLY?”

“RGICLY?” asked mauni baba. “What is that?”

“Rajiv Gandhi Inflation Control Yojana,” explained the son, very seriously.

“We can try, we can try,” said mauni baba going with the flow.

“But where does this inflation come from?”

“Well, over the last few years, the government has increased its expenditure. All this money being spent lands up in the hands of people. And they go out and spend that money. When a greater amount of money chases the same amount of goods and services, prices rise. Food prices particularly work along these lines.”

“Ah. So basically we need to grow more onions and tomatoes.”

“Yes, yes,” said mauni baba. “Its an opportune time to launch IGKTUY.”

“IGKTUY?” asked, the confused son. “What is that?”

“Indira Gandhi Kaandha Tamatar Ugaao Yojana.”

“Kaandha why not just Pyaaz or Pyaaj?” asked the son. “No one understands Kaandha in North India.”

“Oh, I just though IGK comes in a sequence and thus, sounds better,” mauni baba explained.

“IGK or IJK?” asked the son.

“Oh, never mind.”

“But now I get it. Basically inflation is killing growth,” said the son.

“Yes, in fact there is even a term for it.”

“And what is that?”

“Stagflation, which is a combination of stagnation and inflation.”

“Ah, stagflation,” said the son. “I quite like the term. Reminds me of all the stag parties I used to attend.”

“So can I go now?” asked mauni baba.

“Wait, wait, wait,” said the son. “I just understood what you were really trying to say.”

“What?”

“That, mother is essentially responsible for everything. She was the one who got the government to increase its expenditure and spend much more than it earned, which is what finally led to inflation.”

“But I didn’t say that,” mauni baba protested.

“You did not. But that was what you meant,” said a confident son. “Mother won’t like listening to this.”

“Ah. You are making the same mistake as other people.”

“What?”

“They don’t call me mauni baba just for nothing,” said mauni baba and walked out confidently from the room.

The mother soon came back into the room and the son told her everything. As he finished, the mother burst out into a hearty laugh.

“You know, this is quite unbelievable,” she said. “You want me to believe that for the last half an hour mauni baba was speaking and you were listening?”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 13, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)