Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The US Department of Treasury publishes a semi-annual currency report. The latest report released on October 30, 2013, makes a scathing attack at Germany. “Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany’s nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany’s anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro-area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy,” the report points out.

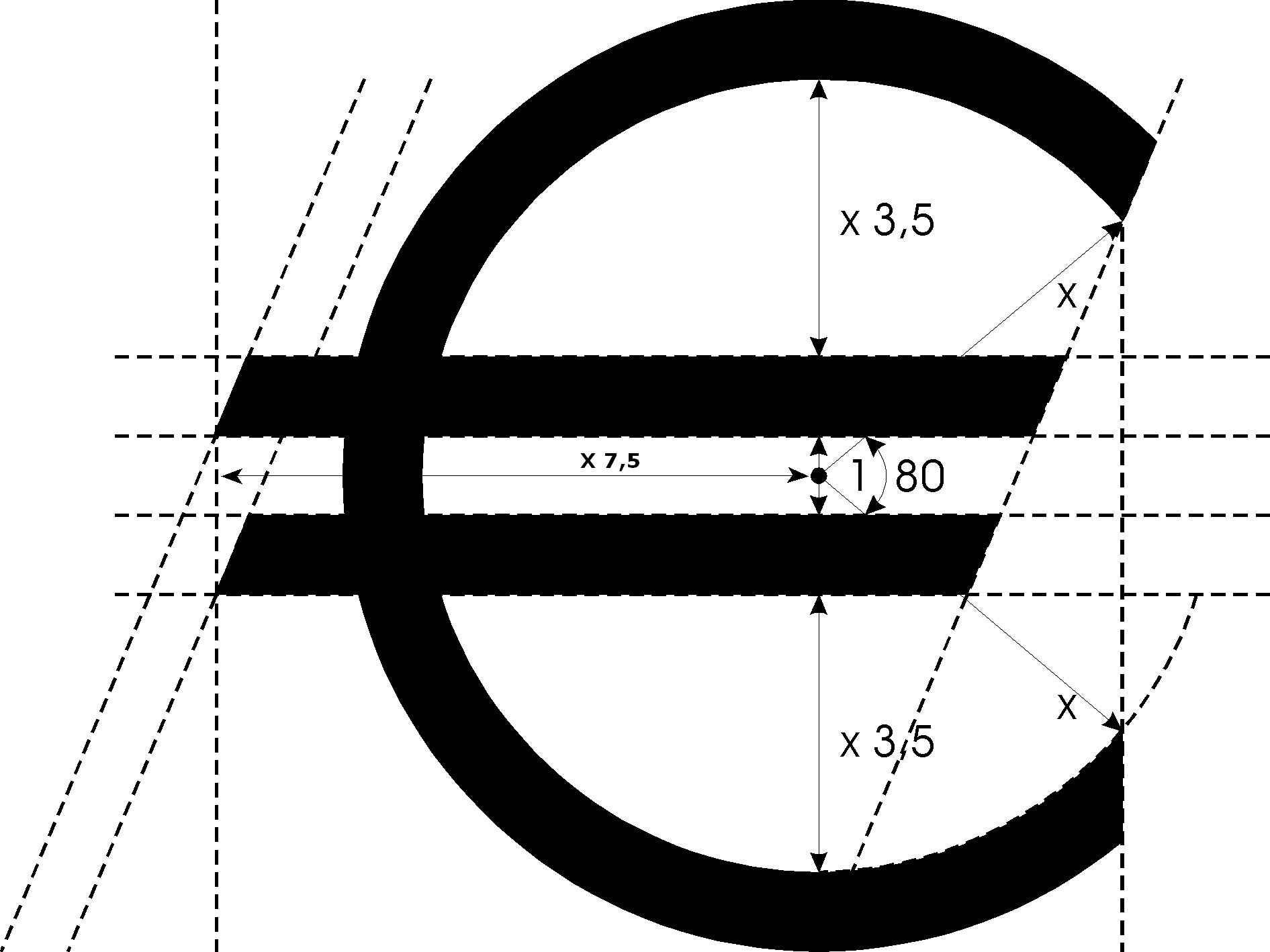

So what does this mean in simple English? Germany has been the export powerhouse of the world. It exports considerably more than it imports. This is the formula it has been trying to force onto other countries of the Eurozone as well. Eurozone is a term used for 17 countries which have adopted euro as their currency.

Some of these countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland etc have not been in the best economic condition over the last few years, with a huge amount of private as well as government debt. This was a result of going overboard with their spending in the years before the financial crisis started.

As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale writes in a report titled Prepare for the next phase of global currency war – should we blame Germany? dated November 14, 2013, “In the run-up tothe crisis they all promoted an inappropriately loose monetary policy that caused a credit and housing bubble, runaway domestic demand growth, ostensibly sound government finances and burgeoning current account deficits, all financed by a surplus nation…predominately Germany.”

Countries like Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland etc went on a borrowing spree, which ultimately led to a housing bubble. When the bubble burst the banking system in these countries was in a mess. They had to be bailed out by the European Central Bank(ECB). At the same time countries were forced to follow austerity measures to control government expenditure. These measures have led to an extremely high level of unemployment in these countries. As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Daily Telegraph pointed out in a recent column “unemployment is 27.8% in Greece, 26.3% in Spain, 17.3% in Cyprus, and 16.5% in Portugal.. it would be far worse had it not been for a mass exodus of EMU refugees….Greek youth unemployment is 62.9%.”

This has led to a situation where internal demand in these countries fell dramatically. A fall in internal demand has meant lower imports. And this in turn has led to exports being greater than imports, and hence a trade surplus( a situation where exports of a country are greater than its imports). The eurozone trade surplus in August 2013 was at $9.5 billion.

Interestingly, the collapse of demand within these countries has also led to a situation where German exports within the Eurozone have fallen. “It is that actually Germany’s trade surplus within the Eurozone has collapsed to almost zero as the GIIPS(Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain)have plunged into depression,” writes Edwards.

This basically means that Germany is importing as much from other countries in the Eurozone as it is exporting to them, leading to a trade surplus of almost zero. But it has more than made up for this by running a higher trade surplus with other parts of the world, primarily United States and large parts of Asia.

Hence, it isn’t surprising that the United States has a problem with Germany. While Germany is exporting goods and services to the United States, it isn’t importing the same amount back from the United States or other parts of the world for that matter. This means that businesses in the United States and other parts of the world are not exporting enough, which in turn has an impact on economic growth.

This formula of running a trade surplus by exporting more and limiting imports has worked very well for Germany. But the question is will it work for the Euro Zone as a whole? Martin Wolf of The Financial Times feels that the strategy may not work for two reasons. “First, the eurozone is far too big to achieve export-led growth, as Germany has done; and, second, the currency is likely to appreciate still further, thereby squeezing the less competitive economies all over again.”

The euro is likely to appreciate in the days to come given that both Japan and United States are printing money big time in the hope of devaluing their currencies. Also, this formula will have political complications as well, given that, exports can only happen if someone else is importing. Every country cannot be an exporter at the same time. Someone has to import as well.

And who will that importer be? Sanjeev Sanyal of Deutsche Bank writes in a report titled Bretton Woods III and the Global Savings Glut dated October 8, 2013 “Reinterpreted to present conditions, the next round of global economic expansion may require the US to revert to its role as the ultimate sink of global demand.”

Or as the French like to put it plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.(the more things change, the more they stay the same).

The article was originally published on www.firstpost.com on November 15, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)