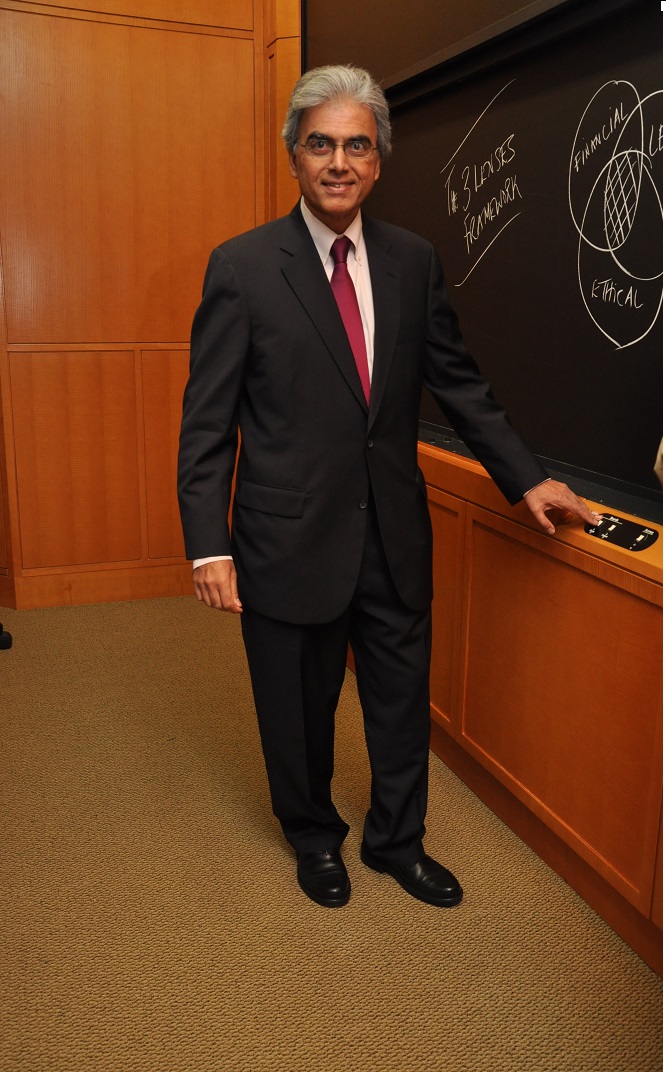

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Rohit Deshpandé is Sebastian S. Kresge Professor of Marketing at Harvard Business School, where he currently teaches in the Owner/President Management Program and in other executive education offerings. Deshpande is the co-author(along with Anjali Raina) of the Harvard Business Review article The Ordinary Heroes of the Taj. He has also written a case study titled Terror at the Taj Bombay.

On the fifth anniversary of 26/11, Deshpande speaks to Firstpost on the heroic behaviour of the employees of Taj Mahal Palace and Tower Hotel, which was occupied by terrorists for three days. “There was one person who was stuck at the Taj and who told this amazing story about a whole bunch of guests being surrounded by a group Taj employees, who calmed them. They surrounded them to make sure that they did not run all over the place and get into harm’s way. They later learned that these were interns, not even regular employees, who were taking care of guests,” says Deshpande.

Give us some background how did the employees of Taj react on the night of 26/11?

The story is that the staff at the Taj reacted uniformly, and that same way was to protect the guest’s safety and to get the guests out of the hotel. Both actions came at the expense of the staff’s own safety. Several of them were wounded and a number of them were killed in the process of doing this.

Were they trained for doing this?

Staff members had no training in security measures. I interviewed people in the kitchen staff. The kitchen took the heaviest casualty. The reason for this was because guests could be taken out on to the road behind Taj through the the back passages from the kitchen galleys. So they started taking hundreds of guests out from the back of the kitchen. The terrorists got to know of this. There was a lot of media attention at that time and somehow they were signalled to this. They went across to the kitchen. The chefs formed a human barrier around the guests and took the bullets. A number of chefs were killed including the number two to Executive Chef Oberoi. There were a number of chefs who were killed and who had been working only for two or three years. Young chefs. These were people who had no training in security measures. And they were instinctively taking care of the guests, and taking them to safety.

That was very brave of them…

One of the people that I interviewed was the vice chairman of Indian Hotels(the company that runs Taj Hotels). He said, these are people who know all the back exits. And the natural human instinct, I am paraphrasing what he said, is to flee. So this is a very curious behaviour. The employees of the Taj Hotel chose not to flee but to stay and help guests out. And then comeback to help more guests out. Many of these people are the sole bread winners in the family. And yet they were doing this. This is counter-intuitive. There is decades of social psychology research that basically says that when there is a flight or flee response, and you are not trained to fight, so you flee.

When you started looking into the reasons, why do you think the staff reacted the way it did, inspite of the fact that they were not trained for it?

So here is the curious story. I asked this question to the senior management, when I was doing these interviews. And they did not know the answer. They could not understand it. Ratan Tata was one of the people that I interviewed. He could not understand it. Raymond Bickson who is the CEO of the company, he could not understand it. So, senior managers couldn’t figure it out. And I asked the employees. I asked why didn’t you run away. And people gave me all kinds of explanations. The General Manager of the hotel, Karambir Kang said, I come from a military family. When I took up this job as the General Manager of the hotel, my father always said remember that you are like the captain of the ship, you are the last one out. And that’s how I felt, I am the last one out.

He stayed on the ship despite what was happening to his own family. There were other people who said, they had more important things to do and so they stayed.

So basically people did what they did and they probably didn’t have an explanation…

It seems somehow what they did was instinctive. They didn’t really have an explanation for it. And we know for sure that they were not trained. But they were independently doing the same thing in different parts of the hotel. The same thing in the general part of it was taking care of the guests but it would translate into different things like calming guests, staying calm themselves, providing food and drink to people through the night. Remember, the attack at the Taj lasted three times longer than it did anywhere else. So actually it is interesting that the fatalities were not much much higher because it lasted three times as long.

So the kitchen etc were functioning?

They were functioning. There were banquet rooms that were sealed off, but they were providing sustenance to the guests in complete darkness. That was the curious part that the employees themselves could not explain.

So what is your explanation?

There is no simple explanation for it. Its a very very complex thing. In the Harvard Business Review(HBR) article that Anjali Raina and I wrote, we looked at the human resource policies, the kinds of people they recruit. How they train them. How they reward them. Undoubtedly that has something to do with it. Raymond Bicskon in his interview said, we hire nice people. You can train anybody to be good at housekeeping, but you can’t train them to be nice.

How do you hire nice people?

We get a little bit of that in the HBR article. There policies tend to be different from other companies. They go to small towns rather than large cities to recruit. This is actually counter intuitive because if you are trying to do recruit an employee who has to do a lot of guest interaction, you want someone who is cosmopolitan, can speak English fluently, can work with international clientèle, etc. You will think that you are more likely to find a person like that in big cities like Mumbai rather than small places like Nashik. They do the opposite. I think that is a part of it. I don’t think they were thinking that would lead them to be prepared for an attack like this. But they were thinking how can they have people who are ambassadors for their guests rather than an ambassador for their brand.

Why did you write only about the Taj and not the Oberoi as well?

There is no deep story to it. The background is that I was actually writing a branding case on Taj Hotels, in the spring of 2009. It was around the time Indian Hotels, had made this major strategic initiative to expand beyond the Taj line of hotels and add Vivanta, Gateway and Ginger brands. To my knowledge there is no other hotel chain in India that actually covers those market segments. So why were they doing this? I came to do that case. Every single interview that I did, the person that interviewed mentioned 26/11.

Why did that happen?

The context of mentioning that was a branding issue. We don’t know whether our brand has been forever besmirched by the tragedy. That people from here on will always associate the Taj with terrorism. The image of the Taj Palace Mumbai will always be an image coloured by smoke rising from the dome. These were the things that people I interviewed said. First, I was going to put that in the opening paragraph of the case but it did not make sense for a branding architecture case, which had nothing to do with. I asked if I could comeback and do a case that had to do with crisis management and brand resurgence. How do you bring your flagship brand back after the crisis? That was the story for the second case. The case was on the Taj. It was not a comparative case on the Indian hotel industry. It was a very simple case which had some marketing and branding angle to it and was focused on the Taj.

The reason for asking the question was very simple. After reading your case the first thought that came to my mind was how had the employees of the Oberoi reacted.

How did they react?

I don’t know.

I don’t know the answer because I don’t have the data. But here is the analytical point. When I teach this case, one of the learning points in the case is the meaning and management of culture. So normally when we teach the concept of culture in the MBA programme, our students are thinking of culture as in corporate culture. Here there are two corporate cultures. There is the Taj corporate culture and there is the Tata corporate culture. So automatically there is a nuance. Then there is the industry culture, which is the hospitality industry, under which will come the Oberoi and a bunch of other competitive hotels. Then there is national culture which has to do with values. Like one of the things that you know from this is atithi devo bhava, which is not a Taj thing. It is an Indian thing.

What are you trying to suggest?

If one thinks of a cultural explanation for the behaviour of the staff at Taj on the night of 26/11, it could be explained by a multiple culture interaction. If it was the hospitality culture that was dominant, one would expect the same thing to have happened at the Oberoi. If it was the Taj culture that was dominant one would expect this not to have happened at the Oberoi. If it was the Tata culture that was dominant one would have expected this to happen if Tata Tea, Tata Motors or TCS had had a crisis of similar proportion. I don’t have data for this but this is a part of our discussion in class, where students are actually trying to grapple with this notion and their learning expands beyond just going to the immediate i.e. what happened in that hotel. For us the learning is not about what happened in that hotel, but is this actually learnable, scalable and generalisable, outside of that hotel. That’s the classroom learning.

When you discuss this case, what kind of explanations people come up with for the behaviour of the Taj employees?

One particular explanation is that this is a one off that could only have happened at that particular hotel. It has to do with the 105 year old history of the Taj Palace hotel in Mumbai and the positive memories especially people in Mumbai associate with it. So, it couldn’t have happened anywhere else. It wouldn’t happen here, at the Taj Land’s End (where the interview took place) for instance. That’s one explanation.

There are explanations that say that this is all about India. It couldn’t have happened outside of India. There is something about the Indian culture that explains it. To some people its regional culture in South Asia or Asia in general and one would not expect this in the West. Then there are people who say this is trainable. This is coachable. This is to do with how you recruit people, and how you train and reward them. So there is a very very wide range of explanations.

You also briefly talked about the Taj brand being tainted with terrorism. How was that overcome?

One part of our discussion that we have during the case study is how do you get guests to comeback to the hotel, after a tragedy like this? This goes back to the issue of the brand being connected with terrorism and therefore people not wanting to go there because they were scared. Taj did an incredible job of reassuring people. If you recall there advertising campaign, they anthropomorphised the building and made it speak in the ad. It basically said, I have withstood generations and seen ups and downs of Indian history and I will stand strong. It was a defiant message, but it was as if the building was speaking. It struck a chord with people, to the point that when the Taj reopened, there were local people who went and lived there. This is an amazing story of resurgence. Also, it is worth remembering that this is happening at the nadir, the low point of the global financial crisis. Hospitality was one of the industries that was impacted the most dramatically. That means what? Luxury hotels occupancy rates were at an all time low, and then this thing happens. This could have wiped out the Taj brand completely. The fact that they rebounded and rebounded in such an amazing way, I think is a testimony to people’s connections with that company, with the hotel, with the staff and what they did in terms of actions and so on.

Anything else that you would like to add?

The other part of the story that comes out here is the Tata story that goes beyond the Taj. The Tata group is known for taking care of its employees. So there is a loyalty that Tata employees have towards their company and towards the Tata group. People that I was interviewing said that they were working for a higher purpose. And after the 26/11 you might know that the Tatas set up a fund to pay the medical expenses of those affected. What is interesting is that the fund covered not only the medical expenses of the Taj employees but everybody and anybody who was affected. This means that they were paying the medical expenses of not only the people who were at the railway station but presumably other people who were Oberoi employees. And that’s just mind boggling.

The interview originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 26, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Month: November 2013

Chidambaram has a dual personality when it comes to inflation

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

It is interesting to follow the views of finance minister P Chidambaram on inflation.

While addressing a banking conference in Mumbai on November 15, 2013, he had this to say: “Monetary policy has no impact on food prices…The only way we can contain food inflation is to augment supplies, but supplies are not entirely elastic. Supplies won’t increase dramatically in a short period of time. For supplies to rise we need great investment, great production, better distribution and better logistics. So we have a challenge.”

Inflation as measured through the consumer price inflation number has ranged between 8.4-12.4% over the past six years. What Chidambaram was essentially saying here is that a major reason behind inflation was food inflation. And there was no way the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) could control food prices by raising the repo rate i.e. the rate at which it lends to banks (or what Chidabaram refers to as monetary policy in his statement).

Fair point. Take the case of vegetables where the demand has risen risen much faster than supply. As Neelkanth Mishra and Ravi Shankar of Credit Suisse write in a report titled Agri 101: Fruits & vegetables—Cost inflation dated October 7, 2013 “Supply did respond, as onion and tomato outputs grew the most. But demand rose faster, with prices supported by rising costs.”

That being the case, there is nothing that the RBI can do about food inflation. Since food inflation has been a major reason behind overall inflation, there is not much that the RBI can do about inflation as well.

Now here is another statement that Chidambaram made on inflation in Singapore on November 21, 2013. “Several steps, including increase in the policy rate, have been taken and we hope that the WPI-based inflation rate will moderate to a level below 5 per cent,” Chidambaram said while addressing the second South Asian Diaspora Convention.

On November 15, Chidambaram felt that increasing the repo rate had no impact on food inflation. But six days later on November 21, he says exactly the opposite thing i.e. the RBI raising the repo rate will help control inflation. The wholesale price inflation (WPI) for the month of October was at 7%, the highest in this financial year.

Food items constitute nearly one fourth of the WPI index. If the wholesale price inflation has to fall from 7% to 5%, there needs to be major drop in food prices, which as Chidambaram said cannot be controlled by the RBI raising the repo rate.

The point is that within a week Chidambaram has made two exactly opposite statements on inflation. On November 15, he felt that the RBI raising the repo rate, had no impact on inflation. But by November 21, he was saying exactly the opposite thing i.e. the RBI raising the repo rate would help control inflation.

So the question is what does Chidambaram really believe in? Or does he change his message as per the need of the audience he is addressing? Does he say one thing in India and another abroad?

It needs to be pointed out that high inflation has been a part of our lives for more or less six years now. And six years is a long period of time to tackle the challenges on the supply side, that Chidambaram feels are the major reason behind inflation. Also, it is worth asking, where did this food inflation suddenly come from?

Economist Surjit Bhalla tackles this issue in his latest column in The Indian Express. As he writes “The logic of Indian inflation is relatively simple…What happens when the government raises the minimum support price (MSP) of foodgrains, especially that of rice and wheat, two crops that account for almost half the value of all the crops for which the government sets the MSP? When the government raises the MSP, the prices of factors of production involved in the production of MSP products — land and labour — also go up. Is it any surprise that rural wages have gone up so fast as to cause labour shortages in an economy with relatively jobless growth for the last nine years? For the last six years, rural wages have gone up by an average of 16 per cent. We don’t have reliable data on rural land values, but anecdotal data suggest that the price of this factor of production has also been rising faster than most prices in the economy. ”

And this in turn has pushed up the price of food, leading to food inflation and in turn consumer price inflation. Initially, the rural wages rose much faster than inflation. But finally the inflation has started to catch up. As Sonal Varma of Nomura Securities points out in a note dated October 24, 2013 “After adjusting for inflation, the decline was even more stark: real rural wage growth moderated to -0.1% y-o-y in August from 9.3% y-o-y in 2012 and 13.4% in 2011.” (y-o-y = year on year).

What also hurts is the fact that rural India spends a larger portion of their income on food, and with food prices rising at an astonishing pace, the rise in rural wages hasn’t been good enough. As Bhalla puts it “a dominantly large share of the expenditure of the poor is on food, and food prices have risen much faster than the average CPI increase of 10 per cent, resulting in a real wage increase of less than 3 per cent per year at best.”

To conclude, this is the real reason behind the high inflation of the last five years. And the RBI cannot do anything about it. And as far as Chidambaram is concerned, the least he can do is stick to offering one reason for inflation.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 25, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Sahara's hide and seek with the Supreme Court and Sebi continues

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Supreme Court has barred Sahara, the finance to reality conglomerate, from selling any immovable property. It has also ordered Sahara boss Subrata Roy and its directors not to leave the country until they submit original title deeds on properties worth Rs 20,000 crore.

On October 28, 2013, the court had directed Sahara to hand over title deeds of properties worth Rs 20,000 crore to the Securities and Exchange Board of India(Sebi). It had also added that a failure to do so would mean that Sahara bossman Subrata Roy would not be allowed to leave India.

On that date, the judges had said “You indulge too much in hide and seek. We cannot trust you any more…There is no escape for you and the money has to come.”

Yesterday, Sahara submitted documents for two parcels of land. This included 106 acres of land in Versova, a western suburb in Mumbai and another 200 acres of land in Vasai, another Western suburb of Mumbai. Sahara provided a detailed valuation of the land carried out by Knight and Frank and another valuer. This put the value of the land in Versova anywhere between Rs 18,800-19,300 crore. The land in Vasai is expected to be worth around Rs 1,000 crore.

This claim of Sahara was immediately contested by the Sebi counsel Arvind Datar. He pointed out that the land in Versova was a part of a green zone where real estate development would not be possible, and that is why there was a plan to develop a golf course there. Sahara contested this claim by saying that the rules had been changed in 2012 and development was possible. To this Datar replied saying that environment ministry would have to agree to this.

Also, the 106 acres of land was a part of a larger disputed area of 614 acres. Sahara is currently in litigation with original owners B Jeejeebhoy Wakaria and associates since 2001.

Over and above this, Datar pointed out that Sahara had supplied only 52 out of the 82 title deeds relating to the collaterals. The rest were certified copies. Datar also challenged Sahara to sell the land and deposit the money. “Let them sell this, find a buyer and deposit the money. Let them sell it and show. Why should Sebi undertake this responsibility? … The October 28, 2013, order was clear – to submit original title deeds of land worth Rs 20,000 crore…The rights and interests of investors must be protected,” he said.

The Supreme Court then asked Sahara to deposit original title deeds of properties worth Rs 20,000 crore anywhere in the country, within two days. This would ensure that the order barring Sahara from selling any property and not allowing its directors to leave the country, would not operate.

So what is the fuss all about? In July 2008, the Reserve Bank of India, ordered Sahara to wind down its parabanking operation run through the Sahara India Financial Corporation, which operated as a Residual Non-Banking Company (RNBC).

This happened after the central bank found several discrepancies in the books of Sahara. It banned Sahara from raising fresh deposits beyond June 30, 2011 and at the same time asked Sahara to repay all its depositors by June 30, 2015.

Sahara India Financial Corporation is big in parts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where it has managed to raise thousands of rupees as deposits over the years. These deposits funded the various businesses of the group from media, films, real estate to even buying international hotels. The group even ran an airline briefly which it sold off to Jet Airways. Most of these businesses are capital intensive businesses which needed a lot of money. The money as mentioned earlier came from the parabanking operation of the group.

Once RBI asked Sahara to wind down its parabanking operation it stuck at the heart of the group’s business model. But soon Sahara started issuing what it called housing bonds. Two group companies, Sahara India Real Estate Corporation Ltd and Sahara Housing Investment Corporation Ltd, issued these bonds technically referred to as optionally fully convertible debentures (OFCDs).

Sahara noted that these OFCDs were being issued to “friends, associates, group companies, workers/ employees and other individuals associated/affiliated or connected in any manner with Sahara India Group of Companies.”

Hence, it did not amount to a public issue and thus, did not require compliance either with the Companies Act, 1956, or the Sebi Act as well as regulation dealing with public issues. This was the way Sahara interpreted the OFCD issue.

As per the Section of the Companies Act, 1956, any offer made to 50 or more people, becomes a public offer. Estimates suggest that the OFCDs were sold to nearly 2.96 crore investors.

This started a series of events which finally led to the Supreme Court judgement as on August 31, 2012. In this judgement, the Court directed the Sahara group to refund investors Rs 24,029 crore to the investors by the end of November.

One of the judges, Justice Khehar said: “It seems the two companies collected money from investors without any sense of responsibility to maintain records pertaining to funds received. It is not easy to overlook that the financial transactions under reference are not akin to transactions of a street hawker or a cigarette retail made from a wooden cabin. The present controversy involves contributions which approximate Rs. 40,000 crore, allegedly collected from the poor rural inhabitants of India. Despite restraint, one is compelled to record that the whole affair seems to be doubtful, dubious and questionable. Money transactions are not expected to be casual, certainly not in the manner expressed by the two companies.”

The November deadline was further extended and Sahara was directed to deposit Rs 5,120 crore immediately, Rs 10,000 crore in January 2013 and the remaining amount in February 2013. Of this amount the group handed over draft of Rs 5,120 crore on December 5, last year, and hasn’t paid anything since then.

At the same time it continued to play ‘hide and seek’ with the Indian judicial system by claiming that it had already repaid most of the amount to the investors and hence, did not have to pay Sebi anymore money. If that was the case why was this not brought to notice of the Supreme Court in August 2012? And why was it brought to notice after the Supreme Court asked it to repay the investors?

As a report in the Business Standard puts it “Its(i.e. Sahara’s) top lawyers have argued that it was not the intention of the court to pay investors twice and that the regulator has to first check several truckloads of documents pertaining to the millions of investors before coming to ask for the balance.”

A report appearing in the Business Standard newspaper in late November 2012 seemed to suggest that agents of the Sahara Group were being pushed to collect sehmat patras (consent letters) from investors to show that their money had already been returned to them. “Agents, estimated to be a million strong, who sold OFCDs, often termed housing bonds, have been ordered to collect these letters, failing which their commissions are being stopped. With these consent letters, many of which are pre-dated, with dates ranging from as early as April to show that refunds were spread over a long period, documents such as account statements and passbooks in the hands of the customers are being collected,” the newspaper reported. Of course, this happened after the Supreme Court judgement in August 2012.

Also money was being transferred to the new Q shop venture launched by the group. As the Business Standard reported“While this documentation process has been on, a significant portion of the money deposited in the accounts have already been transferred to the Q-Shop plan, another money raising plan being marketed as a retail venture.”

It remains to be seen whether Sahara deposits title deeds of properties worth Rs 20,000 crore with Sebi in two days time or not. Or will it manage to come up with a new delaying tactic and continue with its casual approach? In short, all that can be said is that we haven’t heard the last of this issue.

Watch this space.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 22, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Are banks are putting lipstick on a pig to make it look like a princess?

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Borrowing money to run or expand a business is standard operating procedure. The only thing is that the money that has been borrowed needs to be repaid. But sometimes the business does not make enough to repay the borrowed money or debt as it is referred to as.

And some other times, the business does not make enough money even to repay the interest on the debt, that it has taken on. Indian businesses are going through that phase right now. A significant number of them are not making enough money to even repay the interest on the debt that they taken on.

In a report dated November 19, 2013, Ashish Gupta, Prashant Kumar and Kush Shah of Credit Suisse make this point. As they write “Of our sample of listed companies(around 3,700 listed companies), the share of loans with corporates having interest coverage (IC1) <1 went up to 34% (versus 31% in 1Q14). Of these, 80% (78% in 1Q) of loans were with companies which had IC<1 for at least four quarters in the past two years and 26% of them have not covered interest in eight consecutive quarters.”

Now what does this mean in simple English? Around 34% of the listed companies that Credit Suisse follows have an interest coverage ratio of less than one. Interest coverage ratio is essentially the earnings before interest and taxes of a company divided by its interest expense. If the interest coverage ratio is less than one what it means is that the company is not making enough money to pay the interest on its outstanding debt.

Hence, more than one third of the listed companies in the Credit Suisse sample are not making enough money to pay the interest on their debt. Of this lot nearly 80% have had an interest coverage ratio of less than one in at least four quarters in the past two years. And 26% have not made enough money to cover their interest for eight consecutive quarters.

The only conclusion that one can draw from this is that India Inc is sitting on a debt time bomb. “Large corporates continue to be under significant stress as out of the top-50 companies by debt with interest coverage<1 in the second quarter, 23 companies haven’t covered interest in seven or more quarters in past two years and 38 companies were loss making at a profit after tax level,” write the analysts.

A lot of this borrowing was carried out during the easy money years of 2003-2008, when banks were falling over one another to lend money. But now the chickens are coming home to roost. When corporates do not have enough money to repay the interest on their outstanding debt, banks can’t be in the best of shape.

The non performing assets of banks have been on their way up. As economist Madan Sabnavis wrote in a recent column in The Financial Express “Ever since the economy started slipping, companies have found it difficult to service their loans leading to NPAs’ volume increasing from 2.4% in FY11 to 3.0% in FY12 and around 3.6% in FY13. In absolute numbers, they stood at around Rs 1.9 lakh crore in March 2013.”

But what is even more worrying is the rate at which the total amount of restructured loans have been growing. Under restructuring, companies are allowed a certain moratorium on repayment of the outstanding debt. The interest rates to be paid on the outstanding debt are eased at the same time.

In a note dated November 7, 2013, Gupta and Kumar of Credit Suisse had pointed out that “Indian Bank restructured loans were at Rs3.3 trillion (Rs 3,30,000 crore) of which 55% has come through the corporate debt restructuring route.” The total amount of restructured loans are now at 6% of the total loans that banks have given(around 47% of networth of the banks).

And this continues to grow at a huge speed. In October 2013, the corporate debt restructuring cell received new references of Rs 170 billion (Rs 17,000 crore).

Economist Madan Sabnavis throws some more numbers. “The CDR website shows that the volume of restructured debt has increased continuously, touching Rs 2.72 lakh crore as of September 2013 from Rs 0.9 lakh crore in FY09, and was at Rs 2.29 lakh crore by March 2013. In terms of a ratio as a percentage of total advances, CDR was higher at 4.4%, and even traditionally this ratio has been higher than the declared gross NPA ratio...Adding the NPAs to CDRs, the total would stand at 8% for FY13, which is quite scary,” he wrote in The Financial Express.

The reasoning given for corporate debt restructuring is that often a project that the business has borrowed for, does not take off due to external circumstances. This can vary from the environmental clearance not coming in to the land required for the project not being acquired in time.

But with the amount of loans being restructured rising at such a rapid rate leads one to wonder whether the banks genuinely feel that these loans will be repaid or as they just postponing the problem? Take the case of October 2013. New references of Rs 17,000 crore were made to the CDR cell. In comparison for the period of July 1 to September 30, 2013, references to the CDR cell had stood at Rs 24,900 crore.

The Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is clearly worried about this. “You can put lipstick on a pig but it doesn’t become a princess. So dressing up a loan and showing it as restructured and not provisioning for it when it stops paying, is an issue. Anything which postpones a problem than recognising it is to be avoided,” Raghuram Rajan, the RBI governor said a few days back.

But just being worried will not help.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 22, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Consumption story: Mr FM, it’s about low inflation, not low interest rates

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The finance minister P Chidambaram keeps asking public sector banks to cut interest rates. The assumption here is that because interest rates are high people are not buying things. Once banks start cutting interest rates and people start buying things, businesses will grow and the economy will be back on track again. But that is not the correct way to look at the current economic scenario.

In fact, in a piece that I wrote yesterday I had quoted a paragraph written by investment newsletter writer and hedge fund manager John Mauldin. As Mauldin wrote “The belief is that it is demand that is the issue and that lower rates will stimulate increased demand (consumption), presumably by making loans cheaper for businesses and consumers. More leverage is needed! But current policy apparently fails to grasp that the problem is not the lack of consumption: it is the lack of income.”

Mauldin wrote this with respect to the American economy, but it is equally valid for the Indian economy as well. When politicians ask banks to cut interest rates they assume that people are not buying things because interest rates are high, and hence they will have to pay higher EMIs.

This is partially but not totally true.

This belief does not take into account what Mauldin calls “lack of income”. In India, inflation has been fairly high over the last few years, particularly food inflation. What this has meant is that people have had to spend a higher part of their income on meeting their regular expenditure. This has meant lower savings.

aIn fact, a recent survey carried out by Assocham, found that household savings rates have dropped by a huge 40% in the last three years. “Poor households are unable to maintain the consumption levels at current prices while middle income families find their purchasing power erode fast, thus having far less surplus money,” Assocham Secretary General D S Rawat said on the results of the survey.

In fact, government own data, which is a bit dated, points out towards this trend. The household savings declined from over 12% of GDP in 2007 to under 9% in 2011. It would be safe to say that the savings rate would have fallen further since then.

Getting back to the ASSOCHAM survey, 82% of the respondents felt that their salary increments last year were not in sync with the cost of living, which has gone by nearly 40-45%. Given this, these respondents felt that they had to cut down on their standard of living by at least 25%.

All in all, what this means is that the increase in income over the last few years hasn’t been able to keep pace with inflation. What has also not helped is the fact that interest rates on offer on various kinds of deposits have barely managed to keep pace with the rate of inflation. As the Economic Survey of the government for the year 2012-2013, released in February pointed out “High inflation reduces the return on other financial instruments.”

In this scenario, where savings have gone down and income hasn’t gone up enough to keep pace with high inflation, it is difficult to expect people to buy things. If car sales haven’t grown for while, it is simply because people do not have enough money going around and do not feel confident about the future. It also explains why the consumer durables sector is not doing well.

On the flip side the two wheeler sales have remained robust. This was simply because rural wage growth was robust over the last few years. It was 9.3% in 2012 and 13.4% in 2011, after adjusting for inflation. In August 2013, the rural wage growth moderated to -0.1%. It will be interesting to see where two wheeler sales go from here, given that a large number of two wheelers are bought in rural areas.

Given these reasons, for the consumption story to start all over again, it is important that inflation is brought under control. For that to happen, the high government spending which has been the major reason for inflation needs to be reined in. As economist Arvind Subramanian wrote in a recent column in the Business Standard “A pre-condition, of course, is that fiscal deficits (actual not accounting, current not future), and especially spending, need to be brought under greater control.”

Only once that happens, will the consumption story start looking up again. Till then, we will have to unfortunately hear,Chidambaram ask banks to cut interest rates, over and over again.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on November 21, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)