Dekh tere sansar ki halat kya ho gayi bhagwan,

Kitna badal gaya insaan, kitna badal gaya insaan.

— Kavi Pradeep, C Ramachandra, Kavi Pradeep and IS Johar, in Nastik (1954).

Sometime in late December last year I was part of a panel deliberating on where the Indian economy is headed, at a business school in Mumbai.

Towards the end of the discussion, a fund manager sitting towards my right, offered his final reason on why the so-called India growth story was faltering. He said, India has too much democracy.

The room was full of MBA students, just the kind of audience which laps up reasons like the one offered by the fund manager. As soon as he finished speaking, I explained to the audience why the fund manager was wrong, not just because India and the world need democracy, but also from the point of view of economic growth.

Of course, that wasn’t the first time I had heard the too much democracy argument being made in the context of it holding back India’s economic growth. Over the years, I have seen, friends, family members, random acquaintances and men and women I don’t know, make this argument with panache and great confidence.

It seemed, as if, in their minds, they had a picture of this great leader who would come on a white horse, brandishing his sword, and set everything right. They wanted India to be governed by a benevolent autocrat.

Given this, it is hardly surprising that Amitabh Kant, the CEO of the NITI Aayog, and one of central government’s top bureaucrats, said yesterday (December 8, 2020): “Tough reforms are very difficult in the Indian context, we are too much of a democracy.”

The thinking here is that given that India is a democracy, decision making takes time and effort and you can’t just push through economic reforms which can lead to economic growth. Getting things done needs a collaborative effort and hence, is deemed to be difficult. Hence, it would be great to have less democracy, making it easier for a strong leader to push economic reforms through.

Of course, the mainstream media has largely ignored Kant’s comment. But this is an important issue and needs to be discussed.

The question is where does the thinking of too much democracy come from.

Some of it is remnant from the emergency era of 1975-1977, when trains used to apparently run on time. Trains not running on time was basically a manifestation of the general frustration of dealing with the so-called Indian system.

The logic being that, with the then prime minister Indira Gandhi keeping democracy on a backseat, it essentially ensured that the system (represented by trains) actually worked well (represented by trains running on time).

In the recent years, too much democracy hurting India’s future economic prospects comes from the economic success of China. China doesn’t have democracy. The Chinese Communist Party governs the country. In fact, there is no difference between the Party and the government.

This essentially has ensured they can push economic growth without any resistance from the opposition, different sections of the society or the citizens themselves for that matter.

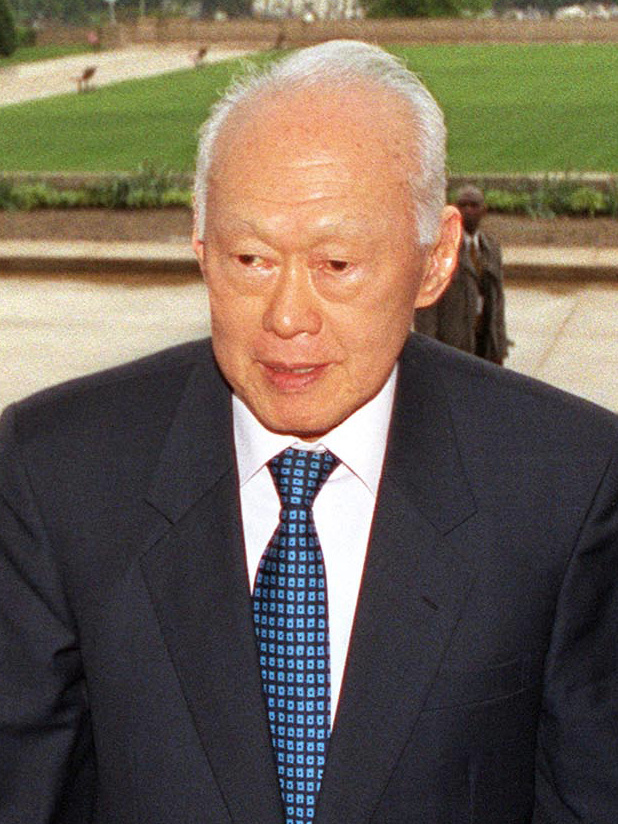

China is not the only example of this phenomenon. Countries like South Korea under Park Chung-hee, Taiwan under Chiang Kai-shek and Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew, made rapid economic surges under leaders who can be categorised as benevolent autocrats.

As economist Vijay Joshi said at the 15th LK Jha memorial lecture at the Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, in December 2017:

“ Fewer than half-a-dozen of the 200-odd countries in the world have achieved super-fast and inclusive growth for two or more decades on the run, and almost all of them were autocracies during their rapid sprints.”

So, history tells us that most super-fast growing countries at different points of time have been autocracies.

Beyond this, there is the so-called India growth story which also leads to the sort of thinking which concludes that too much democracy hurts economic growth. Ravinder Kaur makes this point beautifully in Brand New Nation—Capitalist Dreams and Nationalist Designs in Twenty-First-Century India.

As she writes:

“What is dubbed a growth story in policy-business circles is essentially an enchanting fairy-tale blueprint of economic reforms along with calls of a strong political leader to implement it… After all, capital has always rooted for strong, decisive leaders and centralized governance that can ensure its swift mobility and put the nation’s resources at the disposal of investors.”

A good part of India’s corporate and non-corporate middle class buys into this kind of thinking. They look at themselves as investor-citizens.

This leads to the firm belief that autocracies lead to faster economic growth. Hence, too much democracy is bad for economic growth. Only if India had a stronger leader. QED. Or so goes the thinking.

Dear Reader, this is nothing but very lazy thinking. While, most super-fast growing countries may have been autocracies with a benevolent autocrat at the top, the real question is, are all autocracies with a benevolent autocrat at the top, or at least most of them, super-fast growing countries.

Economist William Easterly makes this point in a research paper titled Benevolent Autocrats. As he writes: “The probability that you are an autocrat IF you are a growth success is 90 percent. This probability seems to influence the discussion in favour of autocrats.”

But that is the wrong question to ask. The question that needs to be asked should be exactly opposite—if a country is governed by an autocrat what are the chances that it will be a growth success? Or as Easterly puts it: “The relevant probability is whether you are a growth success IF you are an autocrat, which is only 10 percent.”

And this is where things get interesting, if we choose to look at data. Ruchir Sharma offers this data in his book The Ten Rules of Successful Nations. Let’s look at this pointwise.

1) In the last three decades, there were 124 cases of a country growing at faster than 5% for a period of ten years. Of these, 64 growth spells came under a democratic regime and 60 under an authoritarian one. Clearly, when it comes to countries growing at a reasonable rate of growth for a period of ten years, democracies do well as well as authoritarian regimes.

2) Let’s up the cut off to an economic growth of 7% or more for a period of ten years. How does the data look in this case? Sharma looked at data of 150 countries going back to 1950. He found 43 cases where a country’s economy grew at an average rate of 7% or more for a period of ten years. Interestingly, 35 of these cases came under authoritarian governments. As mentioned earlier, super-fast growth and autocrats go together. But this just shows one side of things.

3) So, what’s the other side? While super-fast growth in a bulk of cases has happened under authoritarian regimes, so have long economic slumps or economic slowdowns.

As Sharma writes:

“Long slumps are also much more common under authoritarian rule. Since 1950, there have been 138 cases in which, over the course of a full decade, a nation posted an average annual growth rate of less than 3 percent—which feels like a recession in emerging countries. And 100 of those cases unfolded under authoritarian regimes, ranging from Ghana in the 1950s and ’60s to Saudi Arabia and Romania in the 1980s, and Nigeria in the 1990s. The critical flaw of autocracies is this tendency toward extreme, volatile outcomes.”

Also, under authoritarian regimes, economic growth can see wild swings.

So, for every China there is a Zimbabwe as well, which people forget to talk or think about. For every Singapore, there are scores of African dictators who killed thousands of people during their rule and destroyed their respective economies. Hence, while autocracies may lead to super-fast growth, they can also lead to long-term economic stagnation and huge political turmoil.

Also, evidence is clear that steady growth happens best in democracies.

As Sharma writes:

“Together, Sweden, France, Belgium, and Norway have posted only one year of growth faster than 7 percent since 1950. But over that time, these four democracies have all seen their average incomes increase five- to sixfold, to a minimum of more than $30,000, in part because they rarely suffered full years of negative growth.”

Further, if you look at the list of countries with a per-capita income of more than $10,000, all of them are democracies. China, as and when it reaches there, will be the first autocracy, which will make it an exception. An exception, which proves the rule. That is, in the medium to long-term, democracy and economic growth go hand in hand.

At least, that’s what history and data tell us. But don’t let that come in your way of believing the good story of authoritarian regimes run by benevolent autocrats leading to fast economic growth all the time.

It must be true if you believe in it. I mean, Mr Kant surely does. And so do a whole host of middle class Indian men and women.