Vivek Kaul

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government has been talking about economic reforms over the last two months. This after more or less ignoring them since May 2004, when they first came to power.

The rupee’s rapid depreciation against the dollar which started towards the end of May 2013, and which could lead to a serious economic crisis, has forced the government to get a tad serious on the reform front.

The recent Indian experience is no different from how things have happened all over the world. It takes an economic crisis or the possibility of one happening, to get economic reforms going, more often than not.

Nevertheless, the question is why wait till things turn really bad and then start implementing economic reforms? As Alberta Alesina and Allan Drazen ask in a research paper titled Why are Stabilizations Delayed? “Countries often follow policies for extended periods of time which are recognized to be infeasible in the long run. For instance, large deficits implying an explosive path of government debt and accelerating inflation are allowed to continue even though it is apparent that such deficits will have to be eliminated sooner or later. A puzzling question is why these countries do not stabilize immediately, once it becomes apparent that current policies are unsustainable and a that change in policy will have to be adopted eventually.”

The government expenditure in India has exploded over the last few years and more than doubled(gone up by 133%) to Rs 16,65,297 crore between 2007-2008 and 2013-2014. An increase in expenditure has also led to an increase in the fiscal deficit or the difference between what the government earns and what it spends. The fiscal deficit between 2007-2008 and 2013-2014 has gone up by 327.4% to Rs 5,42,499 crore.

It was only recently that the government started taking steps to control the fiscal deficit by trying to control the subsidy it offers on cooking gas, petrol and diesel.

A similar thing has happened on the current account deficit front. The current account deficit(CAD) for the period of 12 months ending March 31, 2013, was at 4.8% of the GDP or $87.8 billion. The CAD is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances.

The level of the CAD at 4.8% of GDP was much higher than the comfortable level of around 3% of GDP. It did not reach such a high level overnight. In fact warnings were made as early 2010 on the mess India would end up in because of the high CAD. And that’s precisely what has happened over the last few months. A high CAD has led to a shortage of dollars, which in turn has led to the depreciation of the rupee against the dollar.

But it was only very recently that the government started to make serious efforts on this front to ensure that the dollars kept coming in. One such move was to increase the allowed level of foreign direct investment(FDI) into a host of business sectors.

What India has seen over the last few months is minor economic reform at best and that too has happened because of the ‘possibility’ of an economic crisis. “The fact that broad-ranging, fundamental economic reform is difficult is attested to by the simple observation that it is quite rare,” writes Val Koromzay in a paper titled Some Reflections on the Political Economy of Reform.

There are many reasons for economic reforms being as rare as they are. Lets look at some reasons which are valid in the Indian context.

A major reason is the fact that politicians do not see beyond their terms. As Dennis Arroyo writes in a research paper titled The Political Economy of Successful Reform: Asian Stratagems “A politician elected to a 3-year term may know that proposed reforms may bear fruit in 8 years. So why scuttle re-election by inflicting temporary economic pain? They would rather optimize over the short term. The benefits of reform do not ripen fast enough to fit the political cycle.”

Lets take the case of allowing FDI in multi-brand foreign retailing (in simple English allow Wal-Marts of the world to operate in India), a decision which was hanging for more than a decade. When FDI was finally allowed into multi-brand retailing in September 2012, it came with too many terms and conditions attached to it. Some of these conditions were done away with recently.

The benefits that India is likely to get in the form of better supply chains, elimination of middle-men, lesser wastage of food, greater consumer choice etc, will not happen overnight. Meanwhile, the government would have to face the heat from opposition parties, traders, and even the press. This largely explains why the Congress led UPA government took a long time to bite the bullet on this front. If the government had made this decision after being re-elected in 2009, the benefits of this reform would have started to become visible by now. As Arroyo puts it “The conventional wisdom is that politicians should use the early honeymoon period to embark on the difficult reforms. The latter will yield fruit by the end of their terms, just in time for the campaign period for reelection. Surprisingly, reform governments do not often take advantage of this window.”

The question is why is the Congress led UPA government so gung-ho now about allowing multi-brand foreign retailing now, given that its benefits are not going to become visible any time soon? One obvious explanation is that India needs dollars that the foreign companies are likely to bring in, if and when they decide to invest in India.

Then again, this is not going to happen overnight. Koromzay has a better explanation for this sudden commitment of the Congress led UPA government to encourage FDI in multi-brand retailing. As he puts it “There is, I think, a definite role for suicide in politics. When a government reaches the point in a reform process where the prospects for re-election become dim, one has much less to lose by continuing with the reform. Politics is a repeated game, and the political parties (if not, usually, their leaders) will be back to fight another election.”

Then there is also the political cost of reform. Take the case of various subsidies that the Congress led UPA government has been doling out over the years. While it is important to cut down these subsidies, it is easier said than done. As William Tompson and Robert Price write in an OECD study titled The Political Economy of Reform “Fiscal reforms in particular often impose risky political costs (Sobel 1998). They entail raising taxes, cutting program budgets, privatizing state enterprises, downsizing the civil service, removing subsidies on sensitive goods, and reallocating funds from one region to another. There will be winners and losers, but it is difficult to pinpoint who are the net gainers a priori. The people feel this short-term pain and ignore the long-term gain.”

It is also important that politicians pitching for reforms effectively communicate their benefits. As Tompson and Price point out “ The importance of meaningful mandates makes effective communication all the more important. Major reforms have usually been accompanied by consistent coordinated efforts to persuade voters and stakeholders of the need for reform and, in particular, to communicate the costs of non-reform.”

Now when was the last time you saw an Indian politician try and explain the benefits of economic reform to the citizens of this country? As economist Vivek Dehejia told me in an interview that I did for the Daily News and Analysis in August 2012, “What makes reforms more difficult now is what I call the original sin of 1991. What happened from 1991 and thereon was reform by stealth. There was never an attempt made to sort of articulate to the Indian voter why are we doing this? What is the sort of the intellectual or the real rationale for this? Why is it that we must open up?”

It is also important that politicians present a united front on the reform front. As Tompson and Price write “The cohesion of the government is also critical. If the government undertaking a reform initiative is not united around the policy, it will send out mixed messages, and opponents will exploit its divisions; defeat is usually the result.” Given that India has had coalition governments since 1996 total ‘cohesion’ has gone missing from its governments, making it all the more difficult to push through economic reform.

What makes reforms further difficult is the fact that there is a section of the population that benefits if the situation continues to be as it is. Take the case of labour law reforms in India. India has too many labour laws which have held back the growth of labour-intensive manufacturing business. Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya in their book India’s Tryst with Destiny estimate that there are as many as 52 independent Central government Acts in the area of labour. Over and above this there are some 150 state level labour laws in India.

And this has held back the growth of firms because the extra costs of satisfying labour laws are so huge that the firms choose to stay small. But the moment there is any talk of labour laws being reformed there are protests from labour unions and political parties (to which the labour unions are affiliated).

Bhagwati and Panagariya estimate that India has nearly 47 crore workers. And of this less than a crore (98 lakh to be precise) were employed in private sector establishments with more than 10 workers in 2007-08. And it is in the interest of these workers and the political parties their unions are affiliated to, that the status quo continues. As Koromzay puts it “reducing rents in the interest of greater efficiency is a task that can be counted on to evoke the opposition of those whose rents are at risk.”

Given these reasons economic reforms are rare and are only pushed through when a country is facing an economic crisis or is likely to face one. India is in a similar situation right now.

Disclosure: The idea for this article came from Vivek Dehejia’s column Why are Reforms Difficult?published in the Business Standard.

This article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 8,2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Vivek Dehejia

Why Congress has learned the wrong lessons from India Shining

Vivek Kaul

Human beings love a good story. And a good story is complete. If something has happened then there is needs to be a ready explanation available for it. Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes about this in Fooled by Randomness. Taleb recounts watching Bloomberg TV, sometime in December 2003 around the time Saddam Hussein was captured in Iraq.

At this point, American government bond prices (commonly referred to as treasury bills) had gone up, and the caption on television explained that this was “due to the capture of Saddam Hussein”. Some thirty minutes later, the price of the American treasury bills went down, and the television caption still said that this was “due to the capture of Saddam Hussein”.

The question is how could the capture of Saddam Hussein lead to have two exactly opposite things? That is simply not possible. But there is a broader point here. If something happens, the human mind needs a reason, an explanation or a cause for it. Without it, the loop is not complete. Hence, the human mind actively seeks causes for events that have happened, whether those causes are the real reasons for the event happening is another issue all together.

As Ed Smith former English cricketer wrote in a recent column “The point, of course, is that causes are being manipulated to fit outcomes. They weren’t causes at all, merely things that happened before the defeat. The ancient Romans had an ironic phrase for this terrible logic – post hoc, ergo proper hoc, “after this, therefore because of this”.”

An excellent example of this phenomenon in an Indian context is the defeat of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) in the 2004 Lok Sabha election. Of the explanations that followed the one that gained most credibility and is still holding on strong, is the India Shining Campaign.

Since the results of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections came in, it has been widely held that BJP lost the elections because of the “insensitive” urban centric India Shining advertising campaign, which ignored the aam aadmi. The irony is that even the BJP came to believe this.

As Arati R Jerath points out in a recent column in The Times of India “Significantly, L K Advani was to acknowledge later that the India Shining slogan was “inappropriate” for an election campaign. In hindsight, many in the BJP realized that the tone and tenor were arrogant and insensitive and that it glossed over prevailing social and economic inequities that the NDA government had failed to address.”

This logic doesn’t hold true against some basic number crunching. The difference in vote share between the Congress led UPA and the BJP led NDA was a little over 2%. The NDA got 33.3% of the vote whereas the UPA won 35.4% of the vote. As economist Vivek Dehejia, the co-auhtor of Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India, said in an interview to Firstpost “That 2% difference in vote share can equally be attributed to a number of other explanations, such as bad luck, as it is to anything else. Or let me put in another way; if you look at those results, basically it came down to a coin toss. A third of the voters voted for the NDA, another third voted for the UPA and a third voted for somebody else.”

Hence, if the NDA had got 1% more vote and UPA had got 1% less vote, the situation would have been totally different. And maybe in that situation, people would have been talking about how the India Shining campaign really worked. Given this, it is not always possible to figure out why something happened. The broader point is that India is too diverse with too many issues at play to attribute the win or a loss in Lok Sabha elections to one cause, which in this case happened to be the India Shining campaign.

But such has been the strength of this explanation that it continues to prevail. In fact, the Congress party has gone at length to explain why there recently launched Bharat Nirman campaign is totally different from the India Shining campaign of 2004. “India Shining was hype, hoopla and spin. Our campaign is different. Bharat Nirman is not a poll campaign, it tells the India story of the past nine years,” the information and broadcasting minister Manish Tewari was recently quoted as saying.

In fact, the India Shining campaign had put too much emphasis on India, people came to believe, and missed out on Bharat. So the Congress has taken great care that the Bharat Nirman campaign caters to Bharat.

That difference notwithstanding prima facie there doesn’t seem to be much difference between India Shining and Bharat Nirman. Both are campaigns launched to highlight the achievements of the incumbent government. India Shining was launched well before the Lok Sabha elections and at that point of time, the BJP leaders maintained that the campaign was meant to attract international investment and beyond that nothing more should be read into it. The Congress seems to be doing the same. As Tewari said “Elections will be held on time. There is no need for speculation.”

Eventually, the BJP got caught into its marketing blitzkrieg and advanced elections by six months. The extent to which Congress wallahs have gone to deny the link between Bharat Nirman and the Lok Sabha elections being advanced, leads this writer to believe that most likely elections will be advanced. As the line from the great British political satire Yes Minister goes “The first rule of politics: Never believe anything until it’s been official denied”. The Congress, like BJP, is in the danger of getting caught in its own spin.

India Shining cost the taxpayer around Rs 150 crore. Bharat Nirman has already spent around Rs 200 crore of the taxpayer money. As an article in the Brand Equity supplement of The Economic Times points out “Sources close to the campaign say that close to Rs 200 crore has been spent on this campaign under various heads. So large is the campaign that in recent months the government has been the single largest consumer of air time and media space on many of the major channels in volume terms.”

What hurts is the fact that the revenue stream of the government at this point of time is stretched. The Ministry of Finance has even gone to the extent of running an amnesty scheme for service tax defaulters. A defaulter can declare and pay his taxes and thereby avoid any fines or even other penal proceedings. If finances are so stretched, why is money being wasted on an advertisement campaign like Bharat Nirman?

More than anything else this government has lost so much credibility that any advertisement campaign cannot help. As Jerath puts it “The campaign is a pathetic attempt to sweep the controversies of the past three years under the carpet. A slick film and a lyrical jingle cannot erase the stench from various corruption scandals or make up for non-performance as food prices rise and the economy slows down.”

The lesson drawn from India Shining should have been that feel good advertisement campaigns run by the government and paid for by the taxpayer, do not really matter in an electoral democracy as diverse as India. Instead the government, which is seen tom-tomming its own achievement, comes across as arrogant. But the parties in power love it. As the Brand Equity points out “The temptation has been too great and a campaign of similar proportions has been released. Perhaps the only difference is that ‘India’ has been replaced by ‘Bharat’ and ‘Shining’ by ‘Nirman’. While the Congress insists that this is not a political campaign (just as the BJP insisted with India Shining), the timing and the quantum of spends seem to belie that.”

The only person Bharat Nirman benefits is the information and broadcasting minister Manish Tewari (and the media houses which get paid for carrying these advertisements), who after taking over as the I&B Minister had to show that he was doing new things that could revitalise the image of the Congress party and he has done precisely that. But this benefit might be short lived because in the days to come if the Congress led UPA loses the next Lok Sabha elections (as it is likely to), then Bharat Nirman will be held responsible for it, like India Shining was.

And then Manish Tewari, might become the new Pramod Mahajan, the man behind the India Shining Campaign.

To conclude, what happens to the taxpayer who finances these expensive campaigns? Well all he can do is sing the old Mukesh song (sung in the style of KL Saigal) “dil jalta hai to jalne de. aansoo na baha, fariyad na kar”.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on May 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Top 10 in Indian non-fiction books: More reasons to skip Chetan Bhagat

Vivek Kaul

It is that time of the year when newspapers, magazines and websites get around to making top 10 lists on various things in the year that was. So here is my list for the top 10 books in the Indian non fiction category (The books appear in a random order).

Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles – Ruchir Sharma (Penguin/Allen Lane -Rs 599)

The book is based around the notion that sustained economic growth cannot be taken for granted.

Only six countries which are classified as emerging markets by the western world have grown at the rate of 5 percent or more over the last 40 years. Only two of these countries, i.e. Taiwan and South Korea, have managed to grow at 5 percent or more for the last 50 years.

The basic point being that the economic growth of countries falters more often than not. “India is already showing some of the warning signs of failed growth stories, including early-onset of confidence,” Sharma writes in the book.

When Sharma said this in what was the first discussion based around the book on an Indian television channel, Montek Singh Ahulwalia, the deputy chairman of the planning commission, did not agree. Ahulwalia, who was a part of the discussion, insisted that a 7 percent economic growth rate was a given. Turned out it wasn’t. The economic growth in India has now slowed down to around 5.5 percent.

Sharma got his timing on the India economic growth story fizzling out absolutely right.

The last I met him in November he told me that the book had sold around 45,000 copies in India. For a non fiction book which doesn’t tell readers how to lose weight those are very good numbers. (You can read Sharma’s core argument here).

In the Company of a Poet – Gulzar In Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir(Rainlight/Rupa -Rs 495)

There is very little quality writing available on the Hindi film industry. Other than biographies on a few top stars nothing much gets written. Gulzar is one exception to this rule. There are several biographies on him, including one by his daughter Meghna. But all these books barely look on the creative side of him. What made Sampooran Singh Kalra, Gulzar? How did he become the multifaceted personality that he did?

There are very few individuals who have the kind of bandwidth that Gulzar does. Other than directing Hindi films, he has written lyrics, stories, screenplays as well as dialogues for them. He has been a documentary film maker as well, having made documentaries on Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. He is also a poet and a successful short story writer. On top of all this he has translated works from Bangla and Marathi into Urdu/Hindi.

In this book, Nasreen Munni Kabir talks to Gulzar and the conversations bring out how Sampooran Singh Kalra became Gulzar. Gulzar talks with great passion about his various creative pursuits in life. From writing the superhit kajrare to what he thinks about Tagore’s English translations. If I had a choice of reading only one book all through this year, this would have to be it.

Durbar – Tavleen Singh (Hachette – Rs 599)

Some of the best writing on the Hindi film industry that I have ever read was by Sadat Hasan Manto. Manto other than being the greatest short writer of his era also wrote Hindi film scripts and hence had access to all the juicy gossip. The point I am trying to make is that only an insider of a system can know how it fully works. But of course he may not be able to write about it, till he is a part of the system. Manto’s writings on Hindi films and its stars in the 1940s only happened once he had moved to Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. When he became an outsider he chose to reveal all that he had learnt as an insider.

Tavleen Singh’s Durbar is along similar lines. As a good friend of Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, during the days when both of them had got nothing to do with politics, she had access to them like probably no other journalist did. Over the years she fell out first with Sonia and then probably with Rajiv as well.

Durbar does have some juicy gossip about the Gandhi family in the seventies. My favourite is the bit where Sonia and Maneka Gandhi had a fight over dog biscuits. But it would be unfair to call it just a book of gossip as some Delhi based reviewers have.

Tavleen Singh offers us some fascinating stuff on Operation Bluestar and the chamchas surrounding the Gandhi family and how they operated. The part that takes the cake though is the fact that Ottavio Quattrocchi and his wife were very close to Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, despite Sonia’s claims now that she barely knew them. If there is one book you should be reading to understand how the political city of Delhi operates and why that has landed India in the shape that it has, this has to be it.

The Sanjay Story – Vinod Mehta (Harper Collins – Rs 499).Technically this book shouldn’t be a part of the list given that it was first published in 1978 and has just been re-issued this year. But this book is as important now as it was probably in the late 1970s, when it first came out.

Mehta does a fascinating job of unravelling the myth around Sanjay Gandhi and concludes that he was the school boy who never grew up.

“Intellectually Sanjay had never encountered complexity. He was an I.S.C and at that educational level you are not likely to learn (through your educational training) the art of resolving involved problems… He himself confessed in 1976 that possibly his strongest intellectual stimulation came from comics,” writes Mehta.

The book goes into great detail about the excesses of the emergency era. From nasbandi to the censors taking over the media, it says it all. Sanjay was not a part of the government in anyway but ruled the country. And things are similar right now!

Patriots and Partisans – Ramachandra Guha (Penguin/Allen Lane – Rs 699)

The trouble with most Delhi based Indian intellectuals is that they have very strong ideologies. There sensitivities are either to the extreme left or the extreme right, and those in the middle are essentially stooges of the Congress party. Given that, India has very few intellectuals who are liberal in the strictest of the terms. Ramachandra Guha is one of them, his respect for Nehru and his slight left leanings notwithstanding. And what of course helps is the fact that he lives in Bangalore and not in Delhi.

His new book Patriots and Partisans is a collection of fifteen essays which largely deal with all that has and is going wrong in India. One of the finest essays in the book is titled A Short History of Congress Chamchagiri. This essay on its own is worth the price of the book. Another fantastic essay is titled Hindutva Hate Mail where Guha writes about the emails he regularly receives from Hindutva fundoos from all over the world.

His personal essays on the Oxford University Press, the closure of the Premier Book Shop in Bangalore and the Economic and Political Weekly are a pleasure to read. If I was allowed only to read two non fiction books this year, this would definitely be the second book. (Read my interview with Ramachandra Guha here).

Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India – Vivek Dehejia and Rupa Subramanya (Vintage Books Random House India – Rs 399)

This little book running into 185 pages was to me the surprise package of this year. The book is along the lines of international bestsellers like Freakonomics and The Undercover Economist. It uses economic theory and borrows heavily from the emerging field of behavioural economics to explain why India and Indians are the way they are.

Other than trying to explain things like why are Indians perpetually late or why do Indian politicians prefer wearing khadi in public and jeans in their private lives, the book also delves into fairly serious issues.

Right from explaining why so many people in Mumbai die while crossing railway lines to explaining why Nehru just could not see the obvious before the 1962 war with China, the book tries to explain a broad gamut of issues.

But the portion of the book that is most relevant right now given the current protests against the rape of a twenty year old woman in Delhi, is the one on the ‘missing women’ of India. Women in India are killed at birth, after birth and as they grow up is the point that the book makes.

My only complain with the book is that I wish it could have been a little longer. Just as I was starting to really enjoy it, the book ended. (Read my interview with Vivek Dehejia here)

Taj Mahal Foxtrot – The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age – Naresh Fernandes (Roli Books – Rs 1295)

Bombay (Mumbai as it is now known as) really inspires people who lives here and even those who come from the outside to write about it. Only that should explain the absolutely fantastic books that keep coming out on the city (No one till date has been able to write a book as grand as Shantaram set in Delhi or a book with so many narratives like Maximum City set in Bangalore).

This year’s Bombay book written by a Mumbaikar has to be Naresh Fernades’s Taj Mahal Foxtrot.

The book goes into the fascinating story of how jazz came to Bombay. It talks about how the migrant musicians from Goa came to Bombay to make a living and became its most famous jazz artists. And they had delightful names like Chic Chocolate and Johnny Baptist. The book also goes into great detail about how many black American jazz artists landed up in Bombay to play and take the city by storm. The grand era that came and went.

While growing up I used to always wonder why did Hindi film music of the 1950s and 1960s sound so Goan. And turns out the best music directors of the era had music arrangers who came belonged to Goa. The book helped me set this doubt to rest.

The Indian Constitution – Madhav Khosla (Oxford University Press – Rs 195)

I picked up this book with great trepidation. I knew that the author Madhav Khosla was a 27 year old. And I did some back calculation to come to the conclusion that he must have been probably 25 years old when he started writing the book. And that made me wonder, how could a 25 year old be writing on a document as voluminous as the Indian constitution is?

But reading the book set my doubts to rest, proving once again, that age is not always related to good scholarship. What makes this book even more remarkable is the fact that in 165 pages of fairly well spaced text, Khosla gives us the history, the present and to some extent the future of the Indian constitution.

His discussion on caste being one of the criteria on the basis of which backwardness is determined in India makes for a fascinating read. Same is true for the section on the anti defection law that India has and how it has evolved over the years.

Lucknow Boy – Vinod Mehta (Penguin – Rs 499)

One of my favourite jokes on Lucknow goes like this. An itinerant traveller gets down from the train on the Lucknow Railway station and lands into a beggar. The beggar asks for Rs 5 to have a cup of tea. The traveller knows that a cup of tea costs Rs 2.50. He points out the same to the beggar.

“Aap nahi peejiyega kya? (Won’t you it be having it as well?),” the beggar replies. The joke reveals the famous tehzeeb of Lucknow.

Vinod Mehta’s Lucknow Boy starts with his childhood days in Lucknow and the tehzeeb it had and it lost over the years. The first eighty pages the book are a beautiful account of Mehta’s growing up years in the city and how he and his friends did things with not a care in the world. Childhood back then was about being children, unlike now.

The second part of the book has Mehta talking about his years as being editor of various newspapers and magazines. This part is very well written and has numerous anecdotes like any good autobiography should, but I liked the book more for Mehta’s description of his carefree childhood than his years dealing with politicians, celebrities and other journalists.

Behind the Beautiful Forevers – Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity – Katherine Boo (Penguin – Rs 499)

As I said a little earlier Mumbai inspires books like no other city in India does. A fascinating read this year has been Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. Indians are typical apprehensive about foreigners writing on their cities. But some of the best Mumbai books have been written by outsiders. Gregory David Roberts who wrote Shantaram arrived in Mumbai having escaped from an Australian prison. There is no better book on Mumbai than Shantaram. The same is true about Suketu Mehta and Maximum City. Mehta was a Bombay boy who went to live in America and came back to write the book that he did.

Boo’s book on Mumbai is set around a slum called Annawadi. She spent nearly three years getting to know the people well enough to write about them. Hence stories of individuals like Kalu, Manju, Abdul, Asha and Sunil, who live in the slum come out very authentic. The book more than anything else I have read on Mumbai ( with the possible exception of Shantaram) brings out the sheer grit that it takes to survive in a city like Mumbai.

So that was my list for what I think were the top 10 Indian non fiction books for the year. One book that you should definitely avoid reading is Chetan Bhagat’s What Young India Wants. Why would you want to read a book which says something like this?

Money spent on bullets doesn’t give returns, money spent on better infrastructure does… In this technology-driven age, do you really think America doesn’t have the information or capability to launch an attack against India? But they don’t want to attack us. They have much to gain from our potential market for American products and cheap outsourcing. Well let’s outsource some of our defence to them, make them feel secure and save money for us. Having a rich, strong friend rarely hurt anyone.

And if that is not enough let me share what Bhagat thinks would happen if women weren’t around. “There would be body odour, socks on the floor and nothing in the fridge to eat.” Need I say anything else?

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 26, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

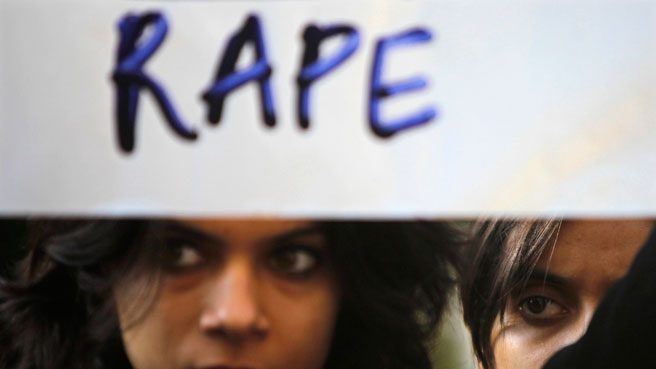

Why women will continue to be raped in India

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Late last night while flipping television channels I saw TV Mohandas Pai, a former CFO and HR Head of Infosys, advocating ‘chemical castration’ for rapists. A leading television anchor also ran his show yesterday around the theme and instigated his celebrity panellists in trying to get them to advocate chemical castration for rapists in India. That is the problem with arguments that emerge due to the heat of the moment. My heart is also thinking along similar lines. It even goes to the extent of telling me that the rapists should be stoned to death. But my head tells me even that won’t make a difference.

Any solution is as good as the system that executes it. In a country like India if anything like chemical castration for committing rapes becomes the order of the day and the police are pushed to solve rape cases faster, what are they likely to do? More often than not they will get hold of some random guy (the homeless, the slum dweller or probably just about the first person they can get their eyes on) beat the shit out of him and get him to confess to it. How do we ensure something like that does not happen? There is absolutely no way to do that.

The other point here is that the police and the judiciary the way they have evolved in India cater more to the rich and powerful rather than to those who ‘need’ the system to work for them. How do we ensure that solutions like ‘chemical castration’ will not be abused by the rich and the powerful?

Someone very close to me for the last two years has been caught up fighting a false case registered against him in New Delhi. It takes is a bribe of Rs 15,000-20,000 to the local thanedar to get a false first information report (FIR) registered. And it takes Rs 500-1000 to the babu at the court to ensure that the case does not come up for hearing, every time it is scheduled. And this in a place like Delhi, which is the capital of the country. Imagine what must be happening in small towns and villages across India? The police in this country have sold out lock, stock and barrel and they shouldn’t be given any further ways of creating more problems for the citizens of this country.

What is interesting is the speed with which Delhi Police has acted in this case and managed to round up most of the rapists. The Delhi High Court has taken suo motu cognizance of the gang-rape and asked the Delhi Police to explain how the offence remained undetected.

Yes the citizens of this country are up in arms against what has happened but that I don’t believe is the real reason why the police and the judiciary have acted with such speed. The only reason for showing the speed that the system has is that the rapists come from the lower strata of the society. They are the ordinary citizens of this country.

As The Times of India reports “The accused have been identified as Ram Singh (33), resident of Ravidas Camp at Sector 3, R K Puram (driver of the bus, DL1PB-0149), his brother Mukesh, 24, (who was driving during the gang rape), Vinay Sharma, 20, (an assistant gym instructor in the area), Pawan Gupta, 18, (fruit seller), Akshay Thakur, 26, (bus cleaner) and another cleaner, Raju, 25.”

If the accused had been the sons of the rich and powerful the entire administration would have by now been working towards getting their names cleared.

The molestation charges against SPS Rathore, an inspector general of police were never proved. He got away with more than a little help from his friends in the government. Manu Sharma, son of Congress politician Venod Sharma, was first acquitted for the murder of model Jessica Lal. With the hue and cry that followed the judgement was overturned and Sharma was sentenced to life imprisonment.

In 2009, Sharma was allowed a parole of 30 days to attend to his sick mother and other matters. His mother was later found attending public functions and Sharma was found partying at a nightclub in Delhi.

Matinee idol Salman Khan had rammed his Toyota Land Cruiser into a bakery in Bandra on September 28,2002, killing one person and injuring four others. The case has dragged on for ten years now. Recently, cop turned lawyer-activist YP Singh revealed that the “Police had deliberately not taken the job of issuing summons seriously. Also, Salman was absent 82 times when summoned by the court.” This is what the rich and powerful in this country can do. The police is at their beck and call. Loads of rape cases go nowhere because the rich and the powerful who are the accused simply bribe their way through the system. When the accused go unpunished or justice takes a long time to be delivered, it makes rape a way of life for Indian men.

That brings me to my final point, the male:female sex ratio in India. As Vivek Dehejia and Rupa Subramanya write in Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India “In 2011, the Census estimates that there were 914 girls for every 1,000 boys for the ages 0-6. This is even worse than in 2001, when there were 927 girls for every 1,000 boys. More pointedly, this ratio is the worst ever since the country’s independence in 1947…In nature, with no sex selection the observed sex ratio is approximately 1,020 males for every 1,000 females.”

What this tells us is that as a country we have a ‘son’ preference. And that leads us to sex-selective abortion and even female infanticide. In simple English we kill our girls before and just after they are born. Delhi and the neigbouring state Haryana have among the lowest sex ratios in the country. And it just doesn’t end there. Debraj Ray and Siwan Anderson have carried out research to suggest that most women who go missing in India do so as adults than at birth or as children. That explains India’s highly skewed sex ratio in favour of men.

Dehejia and Subramanya talk about the research of Ray and Anderson in their book. As they write “They show that about 12 per cent of women in India are missing at birth: they are probably missing due to sex selective abortion or infanticide. Another 25 per cent perish in childbirth. But that’s only a little more than a third of the total. Another 18 per cent go missing during their reproductive period, which picks up among other things deaths during childbirth. But a massive 45 per cent of the total number of missing women go missing in adulthood, something which by definition cannot have anything to do with sex selection.”

Anderson and Ray come up with some more information. “They find that it’s only in Punjab where the majority of missing women are at birth: in fact it’s as high as 60 per cent of the excess female mortality in the state…Two other states show up as having a majority of of their women missing at birth or in childhood (before the age of 15) and it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that they’re Haryana and Rajasthan.”

Hence, we kill our women before birth, after birth and keep killing them as they grow up. In a society like this it is not surprising that men grow up with terribly demented minds and commit heinous rapes like the one in Delhi.

People are appalled. And they want instant justice. Chemical castration. Public hanging. Stoned to death. Anything will do. But what has happened is sheer reflection of the way India has evolved. Women being raped day in and day out is a story of Indian evolution.

And evolution cannot be undone.

So we might take to the streets to protest.

Have candle night vigils.

Protest on Twitter and Facebook.

Call for chemical castration.

Face water cannons from the police.

Sing ballads against the government.

Breakdown and cry while speaking in the Rajya Sabha.

But things won’t change.

As Arvind Kejriwal keeps reminding us “poore system ko badalna padega”. And that of course is easier said than done.

And in a day or two when our conscience is more at peace with itself, we will go back to living our lives like we always have. Because we are like this only.

Meanwhile women will continue to be raped.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 20, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

It’s luck: Explaining Sonia’s rise, BJP’s 2004 loss and cricket debuts

Vivek Dehejia is an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. He is also a regular economic commentator on India for the New York Times India Ink. He has most recently co-authored Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India (Random House India, Rs 399) along with Rupa Subramanya. The book is along the lines of international bestsellers like Freakonomics and The Undercover Economist, and tries to answer a wide array of questions ranging from why did Jawaharlal Nehru did not see the 1962 war with China coming even though there was a lot of evidence to the contrary, to why seatbelts don’t save lives. Dehejia speaks to Vivek Kaul in an exclusive interview. Excerpts:

One of the controversial ideas in your book is that the BJP’s India Shiningcampaign of 2004 was not as much a disaster as is made out to be. Why?

I am glad you asked that. We think it is one of the interesting contributions of the book. I would agree with you that it is a controversial hypothesis because we have this received narrative of the 2004 election – which is that the poor voter had punished the BJP/NDA for the triumphalist India Shining campaign. Even the BJP bought into this interpretation. This has had far-reaching consequences. If you look at the political history of India since 2004, what was the lesson that was drawn? The lesson that everyone drew from the so-called disaster of the India Shining campaign was that you cannot win an election based on economic reform, economic policy and economic success.

And you don’t agree the India Campaign was a disaster…

Our argument here is that if you look at the numbers, if you look not just at the seats won but at the vote shares as well, you get a different story. Yes, there was a swing away from the NDA, but the actual vote share difference between the NDA and the UPA was just over 2 percent. The NDA won 33.3 percent of the vote and the UPA won 35.4 percent of the vote. For us that 2 percent difference in vote share can equally be attributed to a number of other explanations, such as bad luck, as it is to anything else.

Or let me put in another way; if you look at those results, basically it came down to a coin toss. A third of the voters voted for the NDA, another third voted for the UPA and a third voted for somebody else. As we see it, the role of luck and randomness in an outcome should not be underestimated.

That’s a very interesting point…

The NDA might well have won the election. And, in fact, they actually would have won if the DMK hadn’t pulled out their 16 seats at the last minute. And that really was what made the difference. Hence it is very difficult to conclude that it was the voters punishing India Shining. In all Indian elections, there are many regional and local issues at play and then there are issues about the complex way in which alliances work. Our point in the chapter really is that it is a very appealing narrative. We like to have these very convincing explanations because to say well, you know, it was bad luck doesn’t seem like a very satisfying explanation. But if we know that the BJP lost because they had this India Shiningcampaign and the poor voters punished them for it, that appeals to human psychology. We want to have a convincing story that explains everything.

A convincing and simple story that can be broadcast on TV..

That’s right. A story that can fit into a sound byte.

You also talk about the role of luck in Sonia Gandhi‘s life. If it was not at play she would not have ended up at where she is now…

We sort of tell the story as to how she met Rajiv Gandhi at a particular Greek restaurant in Cambridge, England, on a particular day in 1965. That itself was a chance event. Maybe if she did not like Greek food, or if she had gone on a different day! And the number of chance occurrences it took to go from being the shy Italian housewife that she was to being the most powerful person in the country. It took two assassinations and five unexpected deaths. The assassinations, of course, of her mother-in-law and her husband, and then the deaths of five senior Congress leaders (which included Rajesh Pilot, Sitaram Kesri and Madhavrao Scindia). The probability of that happening is so small that you have to call that an accident of fate. Or luck. Or randomness. Or whatever you want to call it.

Any other interesting examples on luck?

We have this study by Shekhar Aiyar and Rodney Ramcharan, two economists of the IMF, who look at the role of luck in test cricket. And they found, amazingly, that the advantage of debuting at home for test cricketers actually had a long lasting effect on their careers – which was really surprising. You would think that if you debut at home, sure it would effect your performance in the debut series, but in fact it has a long-lasting effect.So basically people who debut at home end up playing a lot more…

That’s right. Selectors unfairly punish those who debut abroad and don’t do well. Therefore, you are more likely to be dropped from the side once you debut abroad and don’t do well. But also there could be some learning by doing here. If you debut at home you are able to hone your skills and technique on your home turf and, therefore, you become a better player. Both things could be going on there. But the bottomline is that it is a result of luck because these Test schedules are set months and years in advance, and when someone is picked up for the national side is really the luck of the draw.

An extended portion of your book deals with Jawaharlal Nehru and the fact that for a very long period of time he did not see things heating up with China in 1962, despite there being evidence to the contrary. What is the broader point that you were trying to make?

That forms a central part of our chapter on cognitive failure when we draw on recent behavioural economics literature. The point and the purpose of looking at Nehru in the lead up to the 1962 war was how could something so obvious be missed. It had become clear at that point that China was flexing its muscles. It was a nationalistic state and the border issue was going to be a real problem. But the fact was it apparently caught Nehru by surprise. He himself admitted that he was more or less been living in a dream world before the war. He said: “We were living in an artificial atmosphere of our own creation”. So how could Nehru’s own assessment have been so far off the mark and have changed so radically over a short span of time?

And what did you figure out?

Certainly, one of the several possible interpretations is that Nehru and Krishna Menon (the Defence Minister when the Chinese attacked India) and people around them had succumbed, perhaps to a cognitive failure, where they couldn’t perceive the Chinese threat for what it was. They were looking at it through a different lens.Could you explain that in some detail?

Krishna Menon, for example, was ideologically towards the left and he found it very hard to accept that China, being a socialist state and being an Asian power, could have any threatening impulses towards India. This showed an ideological blind spot to Chinese nationalism that had been detected as long back as 1950 by the shrewd Vallabhbhai Patel. So the broader point we were trying to make is that a strongly-held ideological view can blinker you to some realities that don’t fit in with that view. There is this pattern that one sees where leaders can become overconfident in a lead-up to a crisis because what is happening doesn’t fit their world view of things.

From Nehru you jump to rail accidents in Mumbai…

Yes. A staggering 15,000 people die on railway tracks throughout India every year. Of this 40 percent, or about 6,000 deaths, take place in Mumbai alone on the suburban railway network.

And why is that?

If you look at it from a strictly conventional economic point of view, there is a cost-benefit calculation. So someone who is crossing the tracks at an unfenced point will reckon that he is saving the time it would take for him to get to the next safe crossing, i.e. the foot over-bridge. But that foot over-bridge could be several kilometres away from where he is. If, say, you are a daily wage labourer who has get to the construction site and give your name to the foreman, if you arrive half an hour or 45 minutes late you might miss out on a day of work and so the day’s wages. So the cost can be pretty high. That would be the end of the story from conventional economics and you would say let’s build more foot overbridges to reduce the time cost.

But that is not the whole story?

Let me tell you a little story. Biju Dominic, a former ad man and a co-founder of FinalMile, learned about the daily tragedies on the Mumbai rail system while teaching a class at the railway staff college. So he and his team started gathering some data. They realised that 85 percent of those trying to cross tracks were adult males. Of course, this may also reflect the fact that it is mostly men who are trying to cross the tracks. Also children were most adept at crossing tracks. An interesting finding was that people who are used to crossing tracks tend to underestimate the danger to their lives. This is a classic example of the overconfidence bias, along similar lines that had happened in Nehru’s case before the 1962 war with China. While crossing they don’t consciously realise the risks they are taking. They filter out the boiler plate warning signs and the text signs.

That’s very interesting…

So given the possibility of cognitive failure, it’s possible that some targeted interventions might change that tradeoff. FinalMile came up with three specific interventions. First, they painted alternate sets of railway ties (that’s the series of metal beams that connect the two ends of the track) a bright yellow. This was to help compensate for the psychological fact that people tend to underestimate the speed of large moving objects. With an alternate set of ties painted yellow, someone would be better able to gauge the speed of an oncoming train as it as it passed from the painted to the unpainted ties. Suppose you are in a high a speed train and you are looking out at the landscape, it is hard to tell how fast you are going, unless there is some reference point for the speed. That was one nudge.

What was the second one?The second one was to get the train drivers to switch from a single long warning whistle to two short staccato bursts. Again, this was based on neurological research that showed that the human brain was more receptive to sound that was separated by silence. And the third, the most striking nudge, was an image. People tend to filter out generic boiler-plate kind of warnings. So here they actually hired an actor to portray the wide-eyed horror of someone about to be crushed by an oncoming train and made a poster of it. The poster was vividly visceral enough to really get to someone’s gut, to effect someone psychologically. It is much harder to filter out something like that vis-a-vis a generic sign which says it’s dangerous, don’t cross here. And the poster was put up at points were people crossed tracks. Those were the three interventions.

And how are the results?

They started at Wadala. In the first half of 2010, the number of deaths dropped by 75 percent to nine from the previous year. When we spoke to them in February this year we were told that railways were rolling it out at the Mulund, Vikhroli and Ghatkopar stations. But the other point that we note there is that the success of that really won’t show up in any kind of statistic because if someone looks at the poster and decides not to cross or makes it across safely because of the yellow paint on the ties, it will be the absence of a statistic.

Another interesting piece of research you talk about are seat-belts…

Our inspiration is this classic 1975 article by Sam Peltzman, at the university of Chicago, who wanted to test whether seat-belts saved lives in the United States (US) where everyone had just assumed without argument that seat-belts must save lives. And what Peltzman found was that, in the US, that turned out not be the case. What was going on was that since the cars were now safer, the driving became more rash. The human reaction was, now that my car is a little safer, I can drive a little faster and I don’t need to worry as much about getting into an accident. The human behaviour offset the effects of a well-meaning government programme.

You can find examples of this everywhere. We give an example of sports equipment. There is some evidence now that in team sports where there is a lot of protective gear, you actually see more violence on the pitch. So American football and ice-hockey have a lot more protective gear and so you get a lot more violence. It’s the same thing because the players feel safer as drivers feel when they wear the seat-belt. But in soccer there is relatively very little protective gear and hence very little violence.

How does the seat-belt thing work in an Indian context?It’s not been very much studied but we found this one interesting study by Dinesh Mohan at IIT Delhi. The Delhi seat-belt law came into effect in 2002. What he found was that seat-belts saved very few lives. If you look at his paper, he concludes that the seat-belt law at most saved around 11-15 lives per year in Delhi out of nearly 2,000 fatalities.

Why was that the case?

There are two things going on here. The fatality rate for drivers and front seat passengers was already relatively low. And that dropped a bit after the seat-belt law came in. The deeper explanation is that most of the victims are not the front-seat passengers or the drivers. They are the other people. They are pedestrians. They are two-wheeler drivers. And others. With seat-belts in place drivers are essentially transferring the risk from themselves to the pedestrians.

An interesting part of your book is where you talk about how Indian states that were ruled by native princes are doing much better economically than the states that were ruled directly by the British. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

One of the questions that we like to ask in India is what if we hadn’t been ruled by the British, would we have done better? Or questions like: were the British good for India? And here there are all spectrum of opinions. There was a debate published an American magazineThe New Republic between Niall Ferguson and Amartya Sen which looked at this question. Sen wrote that had India not been colonised by the British then it might have evolved in a different (and) better way than with the colonisation. Then Ferguson replied to that. And Sen had a rejoinder. Ferguson is very much a believer in the British Empire. His argument is that the British Empire in its later phase did a lot of good for its colonies by integrating them into global trade and finance.

So what is the point you are trying to make?

It is very tempting to say that Indian economic performance or growth stagnated during 190 years or 200 years of British rule, and then growth began to take off after independence. The point we make is that by itself it tells you nothing and you have to have a counter-factual scenario. What are you comparing it with? And this is where we draw on the research of Lakshmi Iyer of the Harvard Business School.

What is this research about?

She very interestingly compares the economic performance post-independence of those regions which were directly ruled by the British as against those which were ruled by the princes of princely states. And she shows statistically that the native-ruled regions have done better on average even post-independence. And that is a very striking result. One sort of hypothesis is that the British, to the extent that they were more likely to rule states that generated taxation revenue for them (because tax on land and agriculture was a big source of revenue), may not have invested so much in physical capital and human capital as the Maharajas and Nawabs may have. At least, among the more progressive princely states, they probably realised the good value of education, health and so on and began to invest in that.

Can you give an example?

You can take the example of the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III. He ruled from 1875 to 1939. He had compulsory primary education, including that for girls. He put in place a number of socially progressive policies. That sort of legacy is still being reaped till today. That is one possible explanation and a suggestive idea.

The interview originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 19, 2012.

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected]