Vivek Kaul

The government of India has tried to blame the recent depreciation of the rupee against the US dollar on everything but the state of the Indian economy. Rupee has fallen because Indians buy too much gold, we have often been told over the last few moths.

Rupee has fallen because foreign investors have been withdrawing money in response to the decision of the Federal Reserve of United States to go slow on money printing in the time to come, is another explanation which is often offered. While there is no denying that these factors have been responsible for the fall of the rupee, but the truth is a little more complicated than just that.

Mark Buchanan uses the term disequilibrium thinking in his new book Forecast – What Physics, Meteorology and the Natural Sciences Can Teach Us About Economics. As he writes “one of the key concepts of disequilibrium thinking is the notion of ‘metastability’ which explains how a system can seem stable, yet actually be highly unstable, much like the sulfrous coating on a match, ready to explode if it receives the right kind of spark. Inherently unstable and dangerous situations can persist untroubled for very long periods, yet also guarantee eventual disaster.”

The situation in India was precisely like that. The rupee was more or less stable against the dollar between November 2012 and end of May 2013. It moved in the range of Rs 53.5-Rs 55.5 to a dollar. This stability in no way meant that all was well with the Indian economy.

In a discussion yesterday on NDTV, Ruchir Sharma, Head of Emerging Markets Equity and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, provided a lot of data to show just that. In 2007, the current account deficit of India stood at $8 billion. In technical terms, the current account deficit is the difference between total value of imports and the sum of the total value of its exports and net foreign remittances.

The foreign exchange reserves of India in 2007 stood at $300 billion. So the foreign exchange reserves were 37.5 times the current account deficit. For 2013, the current account deficit is at $90 billion whereas the foreign exchange reserves are down to around $275 billion. So the foreign exchange reserves are now just three times the size of the current account deficit, in comparison to 37.5 times earlier.

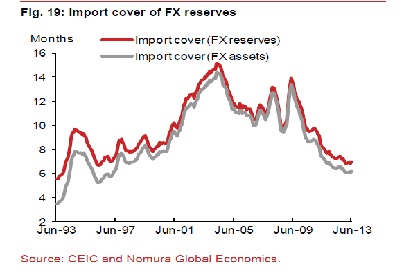

Another worrying point is the import cover (foreign exchange reserves/monthly imports). It currently stands at 5.5 months, the lowest in 15 years. This is very low in comparison to other emerging markets (like China has 18 months of import cover, Brazil has 11 months).

Now what does this mean in simple English? It means that the demand for dollars has gone up much faster than their supply. And this did not happen overnight. It did not happen towards the end of May, when the rupee rapidly started losing value against the dollar. The situation has deteriorated over the last five to six years, while the government was busy doing other things.

Sharma gave out some other numbers as well. In 2007,the short term debt (or debt that needs to be repaid during the course of the year) stood at $80 billion. Currently it stands at around $170 billion. As and when this debt matures, it will have to repaid (unless its rolled over) and that would mean more demand for dollars and a greater pressure on the rupee. Given this, its not surprising that analysts are now predicting that the rupee soon touch 70 to a dollar.

What remains to be seen is whether companies which need to repay this debt are allowed to roll it over. The situation is very tricky given that 25% of Indian companies do not have sufficient cash flow to repay interest on their loans. The amount of loans to be repaid by top 10 Indian corporates has gone up from Rs 1000 billion in 2007 to Rs 6000 billion in 2013. This makes the Indian economy very vulnerable.

Politicians like to compare the current situation to 1991 and tell us that the current situation is not a repeat of 1991. In 1991, the import cover was down to less than a month. Currently it is around 5-6 months (depending on whose calculation you refer to). Hence, the situation is not as bad as 1991.

But the import cover is just one parameter that one can look at. The current account deficit in 1991, stood at 2.5% of the gross domestic product. Currently its around 4.8% of the GDP. Hence, the situation is much worse on this front than in 1991.

The government has tried to control the fall of the rupee against the dollar by making it difficult for Indian companies as well as individuals to take dollars abroad. But that was already happening. The amount of money Indian corporates invested abroad in 2008, stood at $21 billion. It has since come down to $7 billion. The amount of money taken abroad by individuals through legal channels remains minuscule.

The point is that the Indian economy has been extremely vulnerable for sometime, “much like the sulfrous coating on a match, ready to explode if it receives the right kind of spark.” It is just that where the spark will come from leading to explosion of the match, is hard to predict in advance.

As Buchnan puts it “the disequilibrium view….explains in simple terms why the moment of collapse is hard to predict: the arrival of the key triggering event is typically a matter of chance.” And this matter of chance in the Indian context came when Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American Central Bank, addressed the Joint Economic Committee of the American Congress ,on May 23, 2013.

As he said “if we see continued improvement and we have confidence that that is going to be sustained, then we could in — in the next few meetings — we could take a step down in our pace of purchases.”

Over the last few years, the Federal Reserve has been pumping money into the American financial system by printing money and using it to buy bonds. This ensures that there is no shortage of money in the system, which in turn ensures low interest rates. The hope is that at lower interest rates people will borrow and spend more, and this in turn will revive economic growth.

After nearly 5 years, some sort of economic growth has started to comeback in the United States. And given this, the expectation is that the Federal Reserve will start going slow on money printing in the months to come. This has pushed interest rates up in the United States making it more interesting for big international investors to invest their money in the United States than India.

This has led to them withdrawing money from India. Since the end of May nearly $10 billion of foreign money has been withdrawn from the Indian bond market. When these bonds are sold, foreign investors get paid in rupees. They need to convert these rupees into dollars, in order to repatriate their money abroad. This puts pressure on the rupee.

And this is how the decision of the Federal Reserve to go slow on money printing in the days to come has led to the fall of the rupee. This is the story that the government officials and ministers have been trying to sell to us.

But the point to remember is that the decision of the Federal Reserve of United States to go slow on money printing was just the ‘spark’ that was needed to explode the ‘sulfrous coating on the match’ that the Indian economy had become. The spark could have come from somewhere else and the ‘sulfrous coating on the match’ would have still exploded leading to a crash of the rupee. Also, it is important to remember that foreign investors have not abandoned India lock, stock and barrel. When it comes to the bond market they have pulled out money to the tune of $10 billion. But they are still largely invested in the equity market. Since late May around $2 billion has been pulled out of the Indian equity market by the foreign investors. This when they have more than $200 billion invested in it.

Ruchir Sharma’s panelist in the NDTV discussion referred to earlier was Arun Shourie. He called the current rupee crisis a swadeshi crisis. It is time that the government realised this as well because the first step in solving any problem is recognising that it exists.

The article was originally published on www.firstpost.com on August 21, 2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

rupee

Rupee debacle: UPA should stop blaming gold for screw up

“How do I define history?” asked Alan Bennett in the play The History Boys, “It’s just one f@#$%n’ thing after another”.

But this one thing after another has great lessons to offer in the days, weeks, months, years and centuries that follow, if one chooses to learn from it.

Finance minister P Chidambaram and other fire fighters who have been trying to save the Indian economy from sinking, can draw some lessons from the experience of the Mongols in the thirteenth and the fourteenth century.

The Mongol Empire at its peak, in the late 13th and early 14th century, had nearly 25 percent of the world’s population. The British Empire at its peak in the early 20th century covered a greater landmass of the world, but had only around 20 percent of its population. The primary reason for the same was the fact that the Mongols came to rule all of China, which Britain never did.

In 1260 AD, when Kublai Khan became King, there were a number of paper currencies in circulation in China. All these currencies were called in and a new national currency was issued in 1262.

Initially, the Mongols went easy on printing money and the supply was limited. Also, as the use of money spread across a large country like China, there was significant demand for this new money. But from 1275 onwards, the money supply increased dramatically. Between 1275 and 1300, the money supply went up by 32 times.By 1330, the amount of money in supply was 140 times the money supply in 1275.

When money supply increases at a fast pace, the value of money falls and prices go up, as more money chases the same amount of goods. As the value of money falls, the government needs to print more money just to keep meeting its expenditure. This leads to the money supply going up even more, which leads to prices going up further and which, in turn, means more money printing. So the cycle works. That is what seems to have happened in case of Mongol-ruled China.

Gold and silver were prohibited to be used as money and paper money was of very little value as the various Mongol Kings printed more and more of it. Finally, the situation reached such a stage that people started using bamboo and wooden money. This was also prohibited in 1294.

What this tells us is that beyond a certain point the government cannot force its citizens to use something that is losing value as money, just because it deems it to be so. By the middle of the 14th century, the Mongols were compelled to abandon China, a country, they had totally ruined by running the printing press big time.

There is a huge lesson here for Chidambaram and others who have been trying to put a part of the blame on the fall of the rupee against the dollar because of our love for gold. The logic is that Indians are obsessed with buying gold. Since we produce almost no gold of our own, we have to import almost all of it. And every time we import gold we need dollars. This sends up the demand for dollars and drives down the value of the rupee.

This logic has been used to jack up the import duty on gold to 10%. But as Jim Rogers told the Mint in an interview “Indian politicians…suddenly blamed their problems on gold. The three largest imports to India are crude oil, gold and cooking oil. Since they can’t do anything about crude and vegetable oil, the politicians said India’s problems were because of gold, which, in my view, is totally outrageous. But like all politicians across the world, the Indians too needed a scapegoat.”

The question that no politician seems to be answering is, why have Indians really been buying gold, over the last few years? And the answer is ‘high’ inflation. As we saw in Mongol ruled China, it is very difficult to force people to use something that is losing value as money. And rupee has constantly been losing value because of high inflation.

High inflation has led to a situation where the purchasing power of the rupee has fallen dramatically over the last few years. And given that people have been moving their money into gold. As Dylan Grice writes in a newsletter titled On The Intrinsic Value Of Gold, And How Not To Be A Turkey “Now consider gold. In ten years’ time, gold bars will still be gold bars. In fifty years too. And in one hundred. In fact, gold bars held today will still be gold bars in a thousand years from now, and will have roughly the same purchasing power. Therefore, for the purpose of preserving real capital in the long run, gold has a property which is unique in comparison with everything else of which we know: the risk of a loss of purchasing power approaches zero as one goes further into the future. In other words, the risk of a permanent loss of purchasing power is negligible.”

And this is why people are buying gold in India. Gold is the symptom of the problem. Take inflation out of the equation and gold will stop being a problem, though Indians might still continue to buy gold as jewellery. But creating ‘inflation’ is central to the politics of the Congress led UPA. Now that does not mean that people need to suffer because of that? Especially the middle class. As M J Akbar put it in a column in The Times of India “Gold is the minor luxury that a confident economy purchases for its middle class. The cost of gold imports has become a problem only because the economy has imploded.”

Nevertheless people need to protect themselves against the inflationary policies of the government. “Historically, people have understood money’s intrinsic value when they have been forced to, when alternative monies have been rendered unfit for purpose by persistent debasement,” writes Grice.

In ancient times Kings used to mix a base metal like copper with gold or silver coins and keep the gold or silver for themselves. This was referred to as debasement. In modern day terminology, debasement is loss of purchasing power of money due to inflation.

Given this, people will continue to buy gold. The buying may not show up in the official numbers because a lot of gold will simply be smuggled in. A recent Bloomberg report quoted Haresh Soni, New Delhi-based chairman of the All India Gems & Jewellery Trade Federation as saying “Smuggling of gold will increase and the organized industry will be in disarray.”

And other than leading to a loss of revenue for the government, it might have other social consequences as well. As Akbar wrote in his column “If we are not careful we might be staring at 1963, when finance minister Morarji Desai imposed gold control to save foreign exchange. Desai, and a much-weakened prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, could issue orders and change laws but they could not thwart the Indian’s appetite for gold, even when he was in a much more abstemious mood half a century ago. All that happened in the 1960s was that the consumer turned to smugglers. From this emerged underworld icons like Haji Mastan, Kareem Lala and their heir, Dawood Ibrahim. India has paid a heavy price, including the whiplash of terrorism.”

Maybe the new Dawood Ibrahims and Haji Mastaans are just about starting up somewhere.

The piece originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 20, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why govt's surprise theory on rupee collapse doesn't hold

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

‘Comatose’ is a word that can be used to best describe the nine year rule of the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, when it comes to economic reforms.

The only exception to this is the period of the last two months in which the government has taken some measures to open up the Indian economy a little more to the outsiders. At the same time steps have also been taken to allow Indian companies to borrow more freely abroad.

Today’s edition of the Business Standard reports that the finance ministry might “ease norms for (companies) raising funds through an external commercial borrowing(ECB)”. In early July, the Reserve Bank of India had allowed the non banking finance companies(NBFCs) to borrow money through ECBs under the automatic route to finance the import of infrastructure equipment which would be leased to infrastructure projects. Earlier this could happen only through the approval route.

On July 16, the government had announced that it would allow more foreign direct investment (FDI) into 13 sectors of the Indian economy. This included 100% FDI being allowed in the telecom sector.

All this so called ‘reform’ is being sold under the garb of the government having been unprepared for the crash of the rupee against the dollar. As finance minister P Chidambaram said on August 1, 2013 “the rupee depreciation of June, July was quite unexpected.”

Between January and May 2013, the rupee moved in the range of 54-55 against the dollar. After that it started dramatically losing value and currently stands at close to 61 to a dollar. To ensure that the rupee doesn’t fall any further against the dollar, the government has been taking steps to ensure that more dollars come into India and thus boost the value of the rupee against the dollar.

The depreciation of the rupee had caught the government by surprise but now its doing everything it can to arrest its fall. Or so we are being told.

But the surprise theory doesn’t really hold. Anand Tandon, the CEO of JRG Securities makes a very interesting point in the Wealth Insight magazine for August 2013. “In 2010, the ministry of commerce put out a strategy plan and a paper. The paper was titled “Strategy for doubling exports in the next three years”. In it, the ministry assumed that near term trend growth of exports and imports would continue. Based on this, it forecast that India would have a negative merchandise trade balance of $210 billion by 2013. This proved remarkably accurate (the actual figure is $196 billion).”

What Tandon is saying here is that in 2010 a paper was put out by the ministry of commerce which estimated that in three years time by 2013, the trade deficit (i.e. the difference between imports and exports) would be at $210 billion (actually $210.5 billion to be very precise).

When the imports are significantly greater than the exports, what it means is that the country is not earning enough dollars through exports to pay for the imports. In this situation the demand for dollars is greater than the supply, and hence the dollar gains in value against the local currency, which happened to be the rupee in this case.

Also the method used to make this forecast wasn’t rocket science at all. As the report points out “An attempt has been made to forecast the merchandise trade; trends over the next three years, based on the Compound Annual Average Growth Rate (CAGR) during 2002-03 to 2009-10.”

Basically, the authors of the report looked at the average growth rate during the eight year period between 2002 and 2010, and used that to make projections (projections were based on a CAGR of 19.05% for exports and 24.63% for imports) of imports and exports in the years to come.

Given that the report was put out in 2010, so the entire theory about the government being ‘surprised’ and being caught on the wrong foot doesn’t really hold. The high trade deficit is the basic reason behind the rupee losing value rapidly against the dollar.

As Tandon puts it “It is noteworthy that the likely pressure on the rupee was identified as a problem over three years ago, and the current blame attributed to the US Fed action is only perhaps a trigger for the inevitable.”

The question that crops up here is why did the rupee start losing value rapidly against the dollar towards the end of May 2013, and not any time before it? As far as the trade deficit goes, the situation was not very different in January 2013, than it was in May 2013.

While India was not earning enough dollars through exports, dollars kept coming in through other routes. Foreign investors brought money into India to invest in stocks and bonds. Indian companies borrowed abroad in dollars and brought that money back into India. Non Resident Indians(NRIs) also deposited money with Indian banks to at significantly higher interest rates than what they could earn in Western countries.

Things started to change on May 22, 2013, when Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, made a testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, of the US Congress. In this testimony Bernanke said that “a long period of low interest rates has costs and risks. For example, even as low interest rates have helped create jobs and supported the prices of homes and other assets, savers who rely on interest income from savings accounts or government bonds are receiving very low returns. Another cost, one that we take very seriously, is the possibility that very low interest rates, if maintained too long, could undermine financial stability.”

This was interpreted by the market as a hint from Bernanke that the days of the Federal Reserve maintaining low interest rates in order to ensure that people borrowed and spent, would soon be over. Bernanke made the same point in a more direct manner when he addressed the press after the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on June 19, 2013.

International investors had borrowed money at low interest rates prevailing in the United States, and invested that money all over the world, including in Indian bonds, where they could earn higher returns. But after Bernanke’s clarification came in, the return on Indian bonds wasn’t good enough to compensate for the higher interest rate in the United States.

So investors started selling out of Indian bonds in late May 2013. When they sold these bonds they were paid in rupees. They sold these rupees to buy dollars and this led to a rapid depreciation of the rupee.

As mentioned earlier since India’s imports are significantly higher than its exports, there was a shortage of dollars. And once foreign investors started selling out, it only added to that shortage. Hence, the American Federal Reserve just provided the trigger for the rupee crash. It could have very well been something else.

What has added to the pain is the fact that NRI deposits worth nearly $49 billion mature on or before March 31, 2014. With the rupee depreciating against the dollar, the perception of currency risk is high and thus NRIs are likely to repatriate these deposits rather than renew them. This will mean a demand for dollars and thus further pressure on the rupee. Nearly $21 billion of ECBs raised by companies need to be repaid before March 31, 2014. So NRI deposits and ECBs which were a source of dollars earlier will now add to the dollar drain from India.

The solution to India’s dollar problem has been encouraging companies to borrow abroad and opening up or allowing higher FDI in various sectors. The trouble with encouraging companies to borrow abroad is that someday the loan will have to be returned and it would mean a demand for dollars shooting up at that point of time. So in that way, it just postpones the problem rather than solving it.

Allowing FDI in more and more sectors has been the government big mantra in trying to shore up the rupee against the dollar. As Tandon puts it “Of late, it is rare to hear any pronouncements from the finance ministry without it being focussed on foreign direct investment(FDI). Ignoring the findings of the commerce ministry…North Block(where the finance ministry is based) continues to believe that is needed is to remove the pressure on the rupee is to raise FDI limits across various sectors.”

The trouble here is that the foreigners will come with their dollars into India when they want to, not when we want them to. In this situation, the long term solution to India’s dollar problem is to encourage exports. And for that to happen, the ‘weak’ physical infrastructure first needs to be set right.

As the commerce ministry 2010 report pointed out “Infrastructure bottlenecks remain the single most important constraint for achieving accelerated growth of Indian exports.”

The report made estimates of India’s infrastructure gaps on the transport front. For ports it estimated that “in 2014 there will be a shortage of 598 million metric tonnes of cargo handling.”

As far as roads are concerned it estimated that in order to adequately handle export-import cargo, “the ideal length of 4 lanes highway should be 112635 kms and that of 6 lanes 6758 kms by 2014.” This implies a projected gap of “4437 kms for 6 lanes and 66320 kms for 4 lanes highways.”

For Railways “there would be a gap in railway infrastructure of 746 million tons of cargo handling in the year 2014.” And as far as airports are concerned, “poor infrastructure to handle cargo at the airports needs to be addressed to reduce the dwell time of cargo handling and to increase the overall handling of exports cargo,” the report said. “As per the international benchmarks, dwell time for exports is 12 hours, while for imports it is 24 hours as against 3-5 days at Indian airports.”

This is what is required to set the rupee right. Of course, all this is not going to happen anytime soon. And hence, more pain lies ahead.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 5, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Why RBI killed the debt fund

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is doing everything that it can do to stop the rupee from falling against the dollar. Yesterday it announced further measures on that front.

Each bank will now be allowed to borrow only upto 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. Repo rate is the interest rate at which RBI lends to banks in the short term and it currently stands at 7.25%.

Sometime back the RBI had put an overall limit of Rs 75,000 crore, on the amount of money that banks could borrow from it, at the repo rate. This facility of banks borrowing from the RBI at the repo rate is referred to as the liquidity adjustment facility.

The limit of Rs 75,000 crore worked out to around 1% of total deposits of all banks. Now the borrowing limit has been set at an individual bank level. And each bank cannot borrow more than 0.5% of its deposits from the RBI at the repo rate. This move by the RBI is expected bring down the total quantum of funds available to all banks to Rs 37,000 crore, reports The Economic Times.

In another move the RBI tweaked the amount of money that banks need to maintain as a cash reserve ratio(CRR) on a daily basis. Banks currently need to maintain a CRR of 4% i.e. for every Rs 100 of deposits that the banks have, Rs 4 needs to set aside with the RBI.

Currently the banks need to maintain an average CRR of 4% over a reporting fortnight. On a daily basis this number may vary and can even dip under 4% on some days. So the banks need not maintain a CRR of Rs 4 with the RBI for every Rs 100 of deposits they have, on every day.

They are allowed to maintain a CRR of as low as Rs 2.80 (i.e. 70% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. Of course, this means that on other days, the banks will have to maintain a higher CRR, so as to average 4% over the reporting fortnight.

This gives the banks some amount of flexibility. Money put aside to maintain the CRR does not earn any interest. Hence, if on any given day if the bank is short of funds, it can always run down its CRR instead of borrowing money.

But the RBI has now taken away that flexibility. Effective from July 27, 2013, banks will be required to maintain a minimum daily CRR balance of 99 per cent of the requirement. This means that on any given day the banks need to maintain a CRR of Rs 3.96 (99% of 4%) for every Rs 100 of deposits they have. This number could have earlier fallen to Rs 2.80 for every Rs 100 of deposits. The Economic Times reports that this move is expected to suck out Rs 90,000 crore from the financial system.

With so much money being sucked out of the financial system the idea is to make rupee scarce and hence help increase its value against the dollar. As I write this the rupee is worth 59.24 to a dollar. It had closed at 59.76 to a dollar yesterday. So RBI’s moves have had some impact in the short term, or the chances are that the rupee might have crossed 60 to a dollar again today.

But there are side effects to this as well. Banks can now borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI under the liquidity adjustment facility at the repo rate of 7.25%. If they have to borrow money beyond that they need to borrow it at the marginal standing facility rate which is at 10.25%. This is three hundred basis points(one basis point is equal to one hundredth of a percentage) higher than the repo rate at 10.25%. Given that, the banks can borrow only a limited amount of money from the RBI at the repo rate. Hence, the marginal standing facility rate has effectively become the repo rate.

As Pratip Chaudhuri, chairman of State Bank of India told Business Standard “Effectively, the repo rate becomes the marginal standing facility rate, and we have to adjust to this new rate regime. The steps show the central bank wants to stabilise the rupee.”

All this suggests an environment of “tight liquidity” in the Indian financial system. What this also means is that instead of borrowing from the RBI at a significantly higher 10.25%, the banks may sell out on the government bonds they have invested in, whenever they need hard cash.

When many banks and financial institutions sell bonds at the same time, bond prices fall. When bond prices fall, the return or yield, for those who bought the bonds at lower prices, goes up. This is because the amount of interest that is paid on these bonds by the government continues to be the same.

And that is precisely what happened today. The return on the 10 year Indian government bond has risen by a whopping 33 basis points to 8.5%. Returns on other bonds have also jumped.

Debt mutual funds which invest in various kinds of bonds have been severely impacted by the recent moves of the RBI. Since bond prices have fallen, debt mutual funds which invest in these bonds have faced significant losses.

In fact, the data for the kind of losses that debt mutual funds will face today, will only become available by late evening. But their performance has been disastrous over the last one month. And things should be no different today.

Many debt funds have lost as much as 5% over the last one month. And these are funds which give investors a return of 8-10% over a period of one year. So RBI has effectively killed the debt fund investors in India.

But then there was nothing else that it could really do. The RBI has been trying to manage one side of the rupee dollar equation. It has been trying to make rupee scarce by sucking it out of the financial system.

The other thing that it could possibly do is to sell dollars and buy rupees. This will lead to there being enough dollars in the market and thus the rupee will not lose value against the dollar. The trouble is that the RBI has only so many dollars and it cannot create them out of thin air (which it can do with rupees). As the following graph tells us very clearly, India does not have enough foreign exchange reserves in comparison to its imports.

The ratio of foreign exchange reserves divided by imports is a little over six. What this means is that India’s total foreign exchange reserves as of now are good enough to pay for imports of around a little over six months. This is a precarious situation to be in and was only last seen in the 1990s, as is clear from the graph.

The government may be clamping down on gold imports but there are other imports it really doesn’t have much control on. “The commodity intensity of imports is high,” write analysts of Nomura Financial Advisory and Securities in a report titled India: Turbulent Times Ahead. This is because India imports a lot of coal, oil, gas, fertilizer and edible oil. And there is no way that the government can clamp down on the import of these commodities, which are an everyday necessity. Given this, India will continue to need a lot of dollars to import these commodities.

Hence, RBI is not in a situation to sell dollars to control the value of the rupee. So, it has had to resort to taking steps that make the rupee scarce in the financial system.

The trouble is that this has severe negative repercussions on other fronts. Debt fund investors are now reeling under heavy losses. Also, the return on the 10 year bonds has gone up. This means that other borrowers will have to pay higher interest on their loans. Lending to the government is deemed to be the safest form of lending. Given this, returns on other loans need to be higher than the return on lending to the government, to compensate for the greater amount of risk. And this means higher interest rates.

The finance minister P Chidambaram has been calling for lower interest rates to revive economic growth. But he is not going to get them any time soon. The mess is getting messier.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 24, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Six reasons why the PM’s prediction of growth will be right for a change

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Over the last few days a whole host of stock brokerages and financial institutions have downgraded India’s expected rate of economic growth for 2013-14 (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014). Even Prime Minister Manmohan Singh conceded a few days back that the projected growth of 6.5% might be difficult to achieve. “We had targeted 6.5% growth at the time the budget was presented. But it looks as if it will be lower than that,” he said.

Politicians are typically the last ones to concede that things are going wrong. And when they do come around to admitting it, then that is the time one can really believe what they are saying.

So to cut a long story short, for a change, Manmohan Singh’s statement made a few days back might very well come out to be true by the end of this financial year.

Attempts are being made by the government to revive the economy (or at least that is what they would like us to believe), but they are unlikely to lead to any immediate improvement. Analysts at Nomura led by economist Sonal Varma give out some likely reasons for the same in a recent report titled India: turbulent times ahead. “We are downgrading our GDP(gross domestic product) growth forecasts to 5.0% year on year in FY14 (from 5.6%),” write the Nomura analysts.

Lets look at some of the reasons:

a) The government’s current reform zeal isn’t going last for long. Elections in five states are to be held in December 2013/January 2014. These states are Delhi, Mizoram, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chattisgarh. The Congress is not in power in three out of the five states. Also, the party is likely to face a tough time in Delhi. Given these things it is highly unlikely that the party will continue with the “so-called” reform process that it has initiated in the recent past.

One of the lasting beliefs in Indian politics is that economic reform is injurious to electoral reforms. Or as the Nomura authors put it “The window for reforms is fast closing…(It) will close after September…Given the negative consequence of past government inaction(on the reform front), this is a case of too little, too late (to revive growth).”

Also, as the elections approach it is likely that prices of petrol, diesel and cooking gas will not be raised in line with the international price of oil. This happened before the recently held Karnataka assembly elections as well. Hence, the fiscal deficit of the government is likely to continue to go up. “We are concerned with the government’s ability to stick to its budgeted fiscal deficit target,” write the Nomura analysts. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

When a government spends more, it has to borrow more in order to finance that spending. Hence, it “crowds-out” other borrowers, leaving a lesser amount of money for them to borrow. This pushes up interest rates. At higher interest rates people and businesses are less likely to borrow and spend. This impacts economic growth negatively.

b) New investments have dried down: Investments made by companies to expand their current businesses or launch new ones have dried down. “New investment projects announced have fallen from a peak of Rs 2300000 crore in the first quarter of 2009 to Rs 300000 crore in the second quarter of 2013…Investments are long-term decisions and there is a lag between an investment’s announcement and its execution,” write the Nomura authors. Hence, even if a company starts with an investment now, its impact on economic growth will not be felt immediately.

What adds to India’s woes is the fact that sectors like power generation & distribution, infrastructure developers & operators, construction, telecom services etc, which drove the last round of investments between 2004 and 2007 are deep in debt, and in no position to continue investing.

The political uncertainty that prevails will also lead companies to postpone long term capital expenditure decisions till there is hopefully more certainty next year after the Lok Sabha elections in May 2014. As the Nomura analysts write “Given this political uncertainty and an already dismal starting position, we believe that corporates will choose the prudent option of delaying long-term capex decisions until there is more political certainty.”

In fact this trend was visible in the poor results of the heavy engineering and construction major Larsen and Toubro, for the three month period ending June 30, 2013.

c) Banks have become cautious while lending. Even if a company may be ready to invest they might find it difficult to get the loans required to get the project going. This is primarily because the non performing loans and restructured loans of banks have risen to around 10% of their total loans. This figure was at a level of around 4% four years back. As the Nomura authors write “This worsening credit quality has impelled banks to become more risk averse when lending.”

d) Consumer demand will continue to remain sluggish. Car sales have now fallen nine months in a row. High interest rates are often offered as a reason for the falling sales. But as this writer has pointed out in the past, in case of car loans, even a cut of interest rates by 100 basis points brings down the EMI only by around Rs 200.

Hence, people are not buying cars primarily because they are insecure about their jobs and businesses. As the Nomura analysts point out “The job market remains moribund. India does not have good employment data, but given continued job losses in banking and financial services, slowing job growth in the IT sector and sluggish manufacturing sector employment, we do not see a sustainable consumption recovery without an improvement in employment prospects.” Weak consumer demand translates into lower profits for businesses and low economic growth.

One of the main reasons for weak consumer demand has been the fact that till very recently the government did not pass on the increase in the price of oil to the end consumers in the form of a higher price for diesel, petrol or cooking gas. But that has changed now. “Consumers used to be insulated from rising fuel and energy costs (diesel, petrol, LPG cylinder, electricity), but now they are forced to bear a higher burden of adjustment, thereby reducing their disposable income,” the Nomura analysts point out. Add to that a very high food inflation of nearly 10% and you know why the Indian consumer is not spending as much as he was in the past.

e) Indian imports will continue to remain high. The government and the Reserve Bank of India have gone hammer and tongs after gold imports. Through various measures they have managed to bring down gold imports to 31.5 tonnes for the month of June 2013. Hence, gold imports are down by nearly 81% from the 141 tonnes that the country imported in May 2013.

The government’s hatred for gold is primarily because India’s foreign exchange reserves are at very low levels when compared to its imports. Indians foreign exchange reserves are now down to a little over six months of imports, a level last seen in the 1990s. By making it difficult to buy gold, the government hopes to preserve precious foreign exchange reserves. The trouble is that such an alarming fall in gold imports has led the intelligence agencies to believe that a lot of gold is now being smuggled into the country.

The government may be clamping down on gold imports but there are other imports it really doesn’t have much control on. “The commodity intensity of imports is high,” write Nomura analysts as India imports coal, oil, gas, fertilizer and edible oil. And there is no way that the government can clamp down on the import of these commodities, which are an everyday necessity.

When these commodities are imported they need to paid for in dollars. Hence, rupees are sold and dollars are bought. This leads to a surfeit of rupees in the market and a shortage of dollars, and pushes down the value of rupee against the dollar further.

A weaker rupee will lead to Indian oil companies having to pay more for the oil they import. If this increase is not passed onto end consumers (given the upcoming state elections), then it will add to the fiscal deficit of the government.

f) RBI can’t manage the impossible trinity: The RBI currently faces the trilemma of ensuring that the rupee does not go beyond 60 to a dollar, allowing free capital movement and at the same time run an independent monetary policy. This is not possible. Expectations were that the RBI will cut the repo rate in its next monetary policy to help revive economic growth. Repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks.

But at lower interest rates chances are foreign investors will pull out money from the Indian bond market. When they do that they will be paid in rupees. These rupees will be sold and dollars will be bought. When this happens there will be a surfeit of rupees in the market and which will weaken the value of the rupee further against the dollar. This will create problems for the government which will have to bear a higher oil bill. Businesses which have borrowed in dollars will have to pay more in rupees in order to buy the dollars they will need to repay their loans. Imports will become costlier and that will add to inflation, impacting economic growth further.

Given these reasons it is unlikely that India will return to high economic growth rates of 8-9% any time soon. Manmohan Singh might be finally proved right on something.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on July 23, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)