Vivek Kaul

How the mighty fall.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, is now talking about the Indian economy growing at anywhere between 5-5.5% during this financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013).

What is interesting that during the first few months of the financial year he was talking about an economic growth of at least 7%. In fact on a television show in April 2012, which was discussing Ruchir Sharma’s book Breakout Nations, Ahluwalia kept insisting that a 7% economic growth rate was a given.

Turns out it was not. And Ahluwalia is now talking about an economic growth of 5-5.5%, telling us that he has been way off the mark. When someone predicts an economic growth of 7% and the growth turns out to be 6.5% or 7.5%, one really can’t hold the prediction against him. But predicting a 7% growth rate at the beginning of the year, and then later revising it to 5% as the evidence of a slowdown comes through, is being way off the mark.

And when its the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission who has been way off the mark with regard to predicting economic growth, then that leaves one wondering, if he has no idea of which way the economy is headed, how can the other lesser mortals?

Forecasting is difficult business. The typical assumption is that those who are closest to the activity are the best placed to forecast it. So stock analysts are best placed to forecast which way stock markets are headed. The existing IT/telecom companies are best placed to talk about cutting edge technologies of the future. Political pundits are best placed to predict which way the elections will go and so on.

But as we have seen time and again that is not the case. Surprises are always around the corner.

One of the biggest exercises on testing predictions was carried out by Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. He asked various experts to predict the implications of the Cold War that was flaring up between the United States and the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republic at the time.

In the experiment, Tetlock chose 284 people, who made a living by predicting political and economic trends. Over the next 20 years, he asked them to make nearly 100 predictions each, on a variety of likely future events. Would apartheid end in South Africa? Would Michael Gorbachev, the leader of USSR, be ousted in a coup? Would the US go to war in the Persian Gulf? Would the dotcom bubble burst?

By the end of the study in 2003, Tetlock had 82,361 forecasts. What he found was that there was very little agreement among these experts. It didn’t matter which field they were in or what their academic discipline was; they were all bad at forecasting. Interestingly, these experts did slightly better at predicting the future when they were operating outside the area of their so-called expertise.

People get forecasts wrong all the time because they are typically victims of what Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his latest book Anti Fragile calls the Great Turkey Problem. As he writes “A turkey is fed for a thousand days by a butcher; every day confirms to its staff of analysts that butchers love turkeys “with increased statistical confidence.” The butcher will keep feeding the turkey until a few days before Thanksgiving. Then comes that day when it is really not a very good idea to be a turkey. So with the butcher surprising it, the turkey will have a revision of belief – right when its confidence in the statement that the butcher loves turkeys is maximal and “it is very quiet” and soothingly predictable in the life of the turkey.”

When Ahluwalia insisted in late April 2012 that the economy will at least grow at 7% he was being a turkey. He was confident that the good days will continue, and was not taking into account the fact that things could go really bad. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations a book which was released at the beginning of this financial year “India is already showing some of the warning signs of failed growth stories, including early-onset of confidence.”

In fact, expecting a trend to continue, is a typical tendency seen among people who work within the domain of finance and economics. As a risk manager confessed to the Economist in August 2008, “In January 2007 the world looked almost riskless. At the beginning of that year I gathered my team for an off-site meeting to identify our top five risks for the coming 12 months. We were paid to think about the downsides but it was hard to see where the problems would come from. Four years of falling credit spreads, low interest rates, virtually no defaults in our loan portfolio and historically low volatility levels: it was the most benign risk environment we had seen in 20 years.”

Given this, it is no surprise that people who were working in the financial sector on Wall Street and other parts of the world, did not see the financial crisis coming. This happened because they worked with the assumption that the good times that prevailed will continue to go on.

Taleb calls the turkey problem “the mother of all problems” in life. Getting comfortable with the status quo and then assuming that it will continue typically leads to problems in the days to come. That brings me to Ahluwalia’s new prediction. “I would not rule out 7% next year”. He continues to be believe in the number ‘seven’. How seriously should one take that? As hedge fund manager George Soros writes in The New Paradigm for Financial Markets — The Credit Crisis of 2008 and What It Means “People’s understanding is inherently imperfect because they are a part of reality and a part cannot fully comprehend the whole.”

For the current financial year Ahluwalia as someone who closely observes the economic system could not comprehend the ‘whole’. Whether he is able to do that for the next financial year remains to be seen.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 18, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

Ruchir Sharma

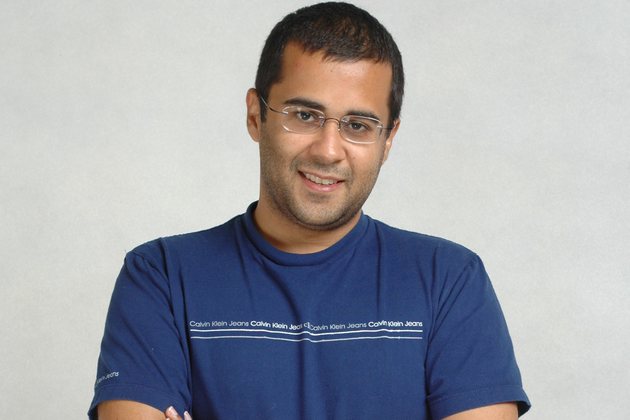

Top 10 in Indian non-fiction books: More reasons to skip Chetan Bhagat

Vivek Kaul

It is that time of the year when newspapers, magazines and websites get around to making top 10 lists on various things in the year that was. So here is my list for the top 10 books in the Indian non fiction category (The books appear in a random order).

Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles – Ruchir Sharma (Penguin/Allen Lane -Rs 599)

The book is based around the notion that sustained economic growth cannot be taken for granted.

Only six countries which are classified as emerging markets by the western world have grown at the rate of 5 percent or more over the last 40 years. Only two of these countries, i.e. Taiwan and South Korea, have managed to grow at 5 percent or more for the last 50 years.

The basic point being that the economic growth of countries falters more often than not. “India is already showing some of the warning signs of failed growth stories, including early-onset of confidence,” Sharma writes in the book.

When Sharma said this in what was the first discussion based around the book on an Indian television channel, Montek Singh Ahulwalia, the deputy chairman of the planning commission, did not agree. Ahulwalia, who was a part of the discussion, insisted that a 7 percent economic growth rate was a given. Turned out it wasn’t. The economic growth in India has now slowed down to around 5.5 percent.

Sharma got his timing on the India economic growth story fizzling out absolutely right.

The last I met him in November he told me that the book had sold around 45,000 copies in India. For a non fiction book which doesn’t tell readers how to lose weight those are very good numbers. (You can read Sharma’s core argument here).

In the Company of a Poet – Gulzar In Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir(Rainlight/Rupa -Rs 495)

There is very little quality writing available on the Hindi film industry. Other than biographies on a few top stars nothing much gets written. Gulzar is one exception to this rule. There are several biographies on him, including one by his daughter Meghna. But all these books barely look on the creative side of him. What made Sampooran Singh Kalra, Gulzar? How did he become the multifaceted personality that he did?

There are very few individuals who have the kind of bandwidth that Gulzar does. Other than directing Hindi films, he has written lyrics, stories, screenplays as well as dialogues for them. He has been a documentary film maker as well, having made documentaries on Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. He is also a poet and a successful short story writer. On top of all this he has translated works from Bangla and Marathi into Urdu/Hindi.

In this book, Nasreen Munni Kabir talks to Gulzar and the conversations bring out how Sampooran Singh Kalra became Gulzar. Gulzar talks with great passion about his various creative pursuits in life. From writing the superhit kajrare to what he thinks about Tagore’s English translations. If I had a choice of reading only one book all through this year, this would have to be it.

Durbar – Tavleen Singh (Hachette – Rs 599)

Some of the best writing on the Hindi film industry that I have ever read was by Sadat Hasan Manto. Manto other than being the greatest short writer of his era also wrote Hindi film scripts and hence had access to all the juicy gossip. The point I am trying to make is that only an insider of a system can know how it fully works. But of course he may not be able to write about it, till he is a part of the system. Manto’s writings on Hindi films and its stars in the 1940s only happened once he had moved to Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. When he became an outsider he chose to reveal all that he had learnt as an insider.

Tavleen Singh’s Durbar is along similar lines. As a good friend of Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, during the days when both of them had got nothing to do with politics, she had access to them like probably no other journalist did. Over the years she fell out first with Sonia and then probably with Rajiv as well.

Durbar does have some juicy gossip about the Gandhi family in the seventies. My favourite is the bit where Sonia and Maneka Gandhi had a fight over dog biscuits. But it would be unfair to call it just a book of gossip as some Delhi based reviewers have.

Tavleen Singh offers us some fascinating stuff on Operation Bluestar and the chamchas surrounding the Gandhi family and how they operated. The part that takes the cake though is the fact that Ottavio Quattrocchi and his wife were very close to Sonia and Rajiv Gandhi, despite Sonia’s claims now that she barely knew them. If there is one book you should be reading to understand how the political city of Delhi operates and why that has landed India in the shape that it has, this has to be it.

The Sanjay Story – Vinod Mehta (Harper Collins – Rs 499).Technically this book shouldn’t be a part of the list given that it was first published in 1978 and has just been re-issued this year. But this book is as important now as it was probably in the late 1970s, when it first came out.

Mehta does a fascinating job of unravelling the myth around Sanjay Gandhi and concludes that he was the school boy who never grew up.

“Intellectually Sanjay had never encountered complexity. He was an I.S.C and at that educational level you are not likely to learn (through your educational training) the art of resolving involved problems… He himself confessed in 1976 that possibly his strongest intellectual stimulation came from comics,” writes Mehta.

The book goes into great detail about the excesses of the emergency era. From nasbandi to the censors taking over the media, it says it all. Sanjay was not a part of the government in anyway but ruled the country. And things are similar right now!

Patriots and Partisans – Ramachandra Guha (Penguin/Allen Lane – Rs 699)

The trouble with most Delhi based Indian intellectuals is that they have very strong ideologies. There sensitivities are either to the extreme left or the extreme right, and those in the middle are essentially stooges of the Congress party. Given that, India has very few intellectuals who are liberal in the strictest of the terms. Ramachandra Guha is one of them, his respect for Nehru and his slight left leanings notwithstanding. And what of course helps is the fact that he lives in Bangalore and not in Delhi.

His new book Patriots and Partisans is a collection of fifteen essays which largely deal with all that has and is going wrong in India. One of the finest essays in the book is titled A Short History of Congress Chamchagiri. This essay on its own is worth the price of the book. Another fantastic essay is titled Hindutva Hate Mail where Guha writes about the emails he regularly receives from Hindutva fundoos from all over the world.

His personal essays on the Oxford University Press, the closure of the Premier Book Shop in Bangalore and the Economic and Political Weekly are a pleasure to read. If I was allowed only to read two non fiction books this year, this would definitely be the second book. (Read my interview with Ramachandra Guha here).

Indianomix – Making Sense of Modern India – Vivek Dehejia and Rupa Subramanya (Vintage Books Random House India – Rs 399)

This little book running into 185 pages was to me the surprise package of this year. The book is along the lines of international bestsellers like Freakonomics and The Undercover Economist. It uses economic theory and borrows heavily from the emerging field of behavioural economics to explain why India and Indians are the way they are.

Other than trying to explain things like why are Indians perpetually late or why do Indian politicians prefer wearing khadi in public and jeans in their private lives, the book also delves into fairly serious issues.

Right from explaining why so many people in Mumbai die while crossing railway lines to explaining why Nehru just could not see the obvious before the 1962 war with China, the book tries to explain a broad gamut of issues.

But the portion of the book that is most relevant right now given the current protests against the rape of a twenty year old woman in Delhi, is the one on the ‘missing women’ of India. Women in India are killed at birth, after birth and as they grow up is the point that the book makes.

My only complain with the book is that I wish it could have been a little longer. Just as I was starting to really enjoy it, the book ended. (Read my interview with Vivek Dehejia here)

Taj Mahal Foxtrot – The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age – Naresh Fernandes (Roli Books – Rs 1295)

Bombay (Mumbai as it is now known as) really inspires people who lives here and even those who come from the outside to write about it. Only that should explain the absolutely fantastic books that keep coming out on the city (No one till date has been able to write a book as grand as Shantaram set in Delhi or a book with so many narratives like Maximum City set in Bangalore).

This year’s Bombay book written by a Mumbaikar has to be Naresh Fernades’s Taj Mahal Foxtrot.

The book goes into the fascinating story of how jazz came to Bombay. It talks about how the migrant musicians from Goa came to Bombay to make a living and became its most famous jazz artists. And they had delightful names like Chic Chocolate and Johnny Baptist. The book also goes into great detail about how many black American jazz artists landed up in Bombay to play and take the city by storm. The grand era that came and went.

While growing up I used to always wonder why did Hindi film music of the 1950s and 1960s sound so Goan. And turns out the best music directors of the era had music arrangers who came belonged to Goa. The book helped me set this doubt to rest.

The Indian Constitution – Madhav Khosla (Oxford University Press – Rs 195)

I picked up this book with great trepidation. I knew that the author Madhav Khosla was a 27 year old. And I did some back calculation to come to the conclusion that he must have been probably 25 years old when he started writing the book. And that made me wonder, how could a 25 year old be writing on a document as voluminous as the Indian constitution is?

But reading the book set my doubts to rest, proving once again, that age is not always related to good scholarship. What makes this book even more remarkable is the fact that in 165 pages of fairly well spaced text, Khosla gives us the history, the present and to some extent the future of the Indian constitution.

His discussion on caste being one of the criteria on the basis of which backwardness is determined in India makes for a fascinating read. Same is true for the section on the anti defection law that India has and how it has evolved over the years.

Lucknow Boy – Vinod Mehta (Penguin – Rs 499)

One of my favourite jokes on Lucknow goes like this. An itinerant traveller gets down from the train on the Lucknow Railway station and lands into a beggar. The beggar asks for Rs 5 to have a cup of tea. The traveller knows that a cup of tea costs Rs 2.50. He points out the same to the beggar.

“Aap nahi peejiyega kya? (Won’t you it be having it as well?),” the beggar replies. The joke reveals the famous tehzeeb of Lucknow.

Vinod Mehta’s Lucknow Boy starts with his childhood days in Lucknow and the tehzeeb it had and it lost over the years. The first eighty pages the book are a beautiful account of Mehta’s growing up years in the city and how he and his friends did things with not a care in the world. Childhood back then was about being children, unlike now.

The second part of the book has Mehta talking about his years as being editor of various newspapers and magazines. This part is very well written and has numerous anecdotes like any good autobiography should, but I liked the book more for Mehta’s description of his carefree childhood than his years dealing with politicians, celebrities and other journalists.

Behind the Beautiful Forevers – Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity – Katherine Boo (Penguin – Rs 499)

As I said a little earlier Mumbai inspires books like no other city in India does. A fascinating read this year has been Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. Indians are typical apprehensive about foreigners writing on their cities. But some of the best Mumbai books have been written by outsiders. Gregory David Roberts who wrote Shantaram arrived in Mumbai having escaped from an Australian prison. There is no better book on Mumbai than Shantaram. The same is true about Suketu Mehta and Maximum City. Mehta was a Bombay boy who went to live in America and came back to write the book that he did.

Boo’s book on Mumbai is set around a slum called Annawadi. She spent nearly three years getting to know the people well enough to write about them. Hence stories of individuals like Kalu, Manju, Abdul, Asha and Sunil, who live in the slum come out very authentic. The book more than anything else I have read on Mumbai ( with the possible exception of Shantaram) brings out the sheer grit that it takes to survive in a city like Mumbai.

So that was my list for what I think were the top 10 Indian non fiction books for the year. One book that you should definitely avoid reading is Chetan Bhagat’s What Young India Wants. Why would you want to read a book which says something like this?

Money spent on bullets doesn’t give returns, money spent on better infrastructure does… In this technology-driven age, do you really think America doesn’t have the information or capability to launch an attack against India? But they don’t want to attack us. They have much to gain from our potential market for American products and cheap outsourcing. Well let’s outsource some of our defence to them, make them feel secure and save money for us. Having a rich, strong friend rarely hurt anyone.

And if that is not enough let me share what Bhagat thinks would happen if women weren’t around. “There would be body odour, socks on the floor and nothing in the fridge to eat.” Need I say anything else?

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 26, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

‘The average lifespan of good govts is just 7-8 years’

When it comes to the growth sweepstakes, it’s like a game of snakes and ladders. It’s not easy for any country to avoid all the snakes, says Ruchir Sharma, head of Emerging Market Equities and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. Most recently he has authored the bestselling Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles.He generally spends one week a month in a developing country somewhere in the world. Based on those experiences he even refers to his book as an ‘economic travelogue’. Sharma was speaking a literary festival in Mumbai on Sunday. Here are a few excerpts from what he said.

The past has no prologue

One of the first rules of the road that I would like to set at the outset is that the past has no prologue. Because what we do is extrapolation and we take what happened in the past and draw straight lines out into the future and say this is what is going to happen in the future. That is just one of the basic rules that does not work.

If you look at it, there are very few countries in the world that can sustain economic success. Only about one third of all economies are able to grow 5% or more for on an average in any decade. Only about one third of the 180 economies in the world. Of the 180 economies in the world only about 35 are developed economies, everyone else is emerging.

What this basically means is that there are these countries which grow for a short span of time and then come back down. It is like the game of snakes and ladders. You sort of go up and get bitten by a snake and come down. Some countries find a lucky ladder and leap frog and get to the top. Very few countries are able to get to the top and very few countries are able to sustain economic success.

Given this, one of the biggest negatives against India at this point is that they have had such an extraordinary decade. And after this extraordinary decade the complacency had set in where we thought of demographics and other factors we would be able to cruise control and nothing else matters as far as growth is concerned and that really has been thrown out of the window.

The average life of a good government is seven to eight years

The other rule is that the average life of a good government is about seven eight years. Typically governments tend to do well for seven to eight years, maximum to a decade and after that the performance of the governments typically tends to decline. This is true even for Russia where the first two terms of Putin was relatively fine. In the UK Margaret Thatcher did very well for about eight nine years and was booted out after that. François Mitterrand faced something similar in France.

There are some exceptions like Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore who are outliers. Usually the average life of good government is seven to eight years and which is why we are concerned about governments that remain in power for too long and very concerned about countries which try and change the constitution to hold onto power for too long. Then there interest is only in ensuring that there power and vested interests are taken care of and they run out of fresh ideas.

So that is the thing with the current government that it has been in power for a long period of time. But typically after seven to eight years governments don’t do well. That is the life cycle. There are very few who do well for a decade or more.

Markets reform when in crisis

The other sort of rule that I have figured about markets is that they only tend to reform when they have their back to the wall. Crisis is what focuses your mind. Otherwise you have a boom, you fitter the gains away and then you sort of slide away and then try and stop it.

That is why I said that of the 180 economies in the world today only 35 are developed because very few are able to grow for a sustained period of time. So you get these sort of growth spurts because they don’t reform.

India’s case is very interesting to look at it. Every 10 years at the start of the decade India seems to consistently have a some sort of a macroeconomic crisis. This was there in the early 1970s, early 1980s, 1991, the early 2000s period when we had the tech boom bust cycle and the growth rate slipped. You can argue that this year has turned out to be similar. The good news for India is that every time we have this macroeconomic crisis or a threat or a currency weakness that is when we take to reform. In 1981 we did that under the IMF, in 1991 we did that, 2001-2002 the same thing happened and we seem to be doing that now.

Very few emerging markets have taken to reform in a proactive manner. They tend to reform with their backs to the wall and that is what China did with such an exception. China pro-actively reformed every 4 to 5 years and came up with some big bang reform. They were proactive about it and not complacent about it. You can argue that complacence is setting in now. But the last thirty years has been a stream of pro-activeness.

Premature populism is a bad sign

The other sort of rule is to look for is populism. This is one of the things which is very hard to say because it is politically incorrect, but building a welfare state pre-maturely creates the wrong incentives. Schemes like NREGA keep too many farmers at the farm. A mass form of populism which has taken place in India over the last ten years. On the other hand if you look at the successful economies like Korea, Taiwan or even China, they did very little in terms of the welfare state at this stage of their economic development. There focus was lets get grow, and make the pie big enough. And then we will share the the pie later.

Today you can argue that countries like Korea and Taiwan don’t do enough of a welfare state. The Korea story is very fascinating. It is one of the most equal societies. And it is a very well educated society and Korean women are very well educated. Yet their participation in the labour force is very low. And that is because many of them are not able to leave their children at home and go to work because they don’t have a good enough child care support system. They don’t spend enough on those kids. In Korea’s case I can argue they need more welfare and in India’s case I can argue that there is too much welfare.

Social spending as a share of GDP for Korea and India is equal even though Korea’s per capita income is more than ten times higher than India’s per capita income. So to have too much populism prematurely is a bad sign.

The billionaire’s index

One of the popular parts of the book that resonated with many people was the billionaire’s index. Forbes publishes a billionaire’s list in March. It sort pours over across the world to see who are the good billionaires, who are the bad billionaires and stuff like that. I think the key dimension will be to look at the billionaire’s index which is that you need to figure out that in case of how many of these billionaires the wealth has been created because they are genuinely productive billionaires. They are creating wealth in sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing etc. When you have wealth created in those sectors you are respected but when you have wealth created in so called sectors where the benefit has happened because you had a good government connection, that is just not good. In India’s case we saw many such billionaires rise over the past decade which is what made me somewhat concerned. It is a bad sign for democracy as well .

Other thing to see in the billionaire’s index is that you need churn, you need new people to come up the list. You don’t need holders of the past always there. The third thing is that you need the concentration of the billionaires as a share of the economy to not be that high. That leads to resentment. Having said that India respects its billionaires a lot.

The James Bond moment

When I go and meet billionaires in countries such as Mexico, Brazil, or even Russia, in all those countries you have all these billionaires with a whole bunch of armed bodyguards. There are scared to go out on the streets on their own because they fear that they are going to be attacked. In places like Brazil, you will find a sale of luxury cars is quite low for a country of that size, because people are scared to display that kind of wealth. And if there are luxury cars they are all bullet proofed because they are scared about what is going to happen.

On the other hand Brazil tops the list of maximum number of helicopters sold. The only time I feel like James Bond is when I go to Sao Paulo in Brazil. In Sao Paulo the traffic is really bad but the permission to fly helicopters is quite easy to get unlike what happens in Mumbai.

My sort of James Bond moment is after you finish your meeting they will take you to the roof of the building where there is a helipad waiting for you, you run to the helipad, you take the helicopter and go to the next destination. And you see the aerial view of Sao Paulo and there is a whole bunch of helipads up there on top.

That is a sign. It is a sign of poor infrastructure and you are using these helicopters to short circuit roads and to sort of not care about what is happening on the street and take a helicopter across it. And then you got gated community where they you behind these fortresses. And I think that is just a bad sign. Brazil is the most extreme and my James Bond moment will remain and therefore I relish my trips to Brazil.

The Four Seasons Index

What I do not relish going to Brazil let me tell you are the costs. And this is one my other rules in terms of the cost with the Four Seasons index. I am fortunate that I get to stay in the Four Seasons hotel in all these countries. And I think its good benchmark to look at a country to figure out whether its cheap or expensive?

In Brazil when I go I find the rates are exorbitantly expensive. To get a top hotel on a trip to Rio de Janeiro you pay $800-1000 a night. And that is really exorbitant. You go to East Asia, places like Jakarta and Bangkok, you pay about $200-300 a night, and that is pretty competitive. In places like Brazil and Russia you pay $800-1000 a night. And the currency seems very expensive. My colleagues went to Brazil last year and one of them bought a a t-shirt. The t-shirt cost more than $100 and it did not last even a single wash. So terrible quality and you are like paying a huge price for that.

Hence, Brazil has been one of the big laggards because of expensive currency. This year the Brazil’s growth rate will be only 1%. When you have expensive currency it is bad news. India on the other hand one of the positive would be currently is that the currency is extremely competitive at this point of time.

But isn’t a weak rupee a sign of weakness?

People are concerned that this is a sign of real weakness in India and whether India is about to face a balance of payment crisis? Is money going to leave the country in a huge way because is the currency is quite weak?

One of the rules of the road I watch out for is that one of the first people who take money out of the country when they think that the country is going to face a crisis are the locals. And this is counter-intuitive because most people like to believe that its the foreigners who flee when they sight trouble.

So I am always watching what are the locals doing? Are they taking money out of the country? Or are they bringing money in? This happened in India in 1991. Similarly in East Asia in the late 1990s.

The good thing for India on a balance of payment front is that we don’t have too much outflow on that front. We don’t have mysterious outflows which show up on the RBI balance sheet. You know that is going on when the hawala rates are way way more expensive than what your official rates are. You don’t see such signs in India. So it seems that the currency weakness is happening in an orderly manner. The currency is adjusting for the overvaluation because of our inflation.

Efficient Corruption

The businesses are complaining about investing in India. They are saying that listen we are better off investing abroad rather than India because the cost of India doing business has become very high. So they are even going to places like Indonesia etc. So I asked one businessman in India, that isn’t Indonesia also very corrupt? So why are you investing in Indonesia? His answer was very interesting. But Indonesia is something what you call efficient corruption compared to India which is like in Indonesia if you pay money to somebody the work is done.

And I have got first hand evidence of efficient corruption. I went to Indonesia and I was struck in Jakarta in a traffic jam. The person who was taking me around Jakarta called a number up and without me knowing police escorts arrive. What you do there you pay a $100-200, and call up a number, police escorts arrive, who clear the traffic for you and take you to the airport. That is efficient corruption for you as far as that country is concerned.

The second city rule

One of the other rules that I looked for is the second city rule. If you look at all the successful economies across the world that whenever there is a growth spurt you get the rise of second cities in that country.

As far as India is concerned we don’t have one prominent city and everything else below that. We have four to five mega cities. And here is the difference with China. You look at India’s mega cities with populations of 10 million, 16% of India’s population lives in these mega cities. And that is why these mega cities are bleeding because that is way too high a number. You take the case of China 5% of the population lives in the mega cities of China .

The question is why? Because there has been a huge rise in the second -tier cities in China. If you look at the last fifteen year or so more than 20 second tier cities have come up in China. And second tier I define as cities which had a population of a less than 100,000 but now have a population of a more than a million. In India’s case only six such cities have come up over the last forty to fifty years. And that is the real difference and so there is big pressure on the big cities in India.

A 5% growth rate is a big disappointment

So is India going to be a breakout nation or not? And here is what I find quite fascinating as far as India is concerned. When the book came out this year, the general response was that by giving India a 50% chance of becoming a breakout nation, you are being too pessimistic.

And how I define breakout nations? I define breakout nations as those countries which are going to do better than other countries in the same per capita income class and countries which will grow faster than expectations.

So those are two my major major definitions of breakout nations. And why those two? Because if people tell me that if India grows at 5% what is the big deal because that is still faster than the US or many of the European countries. And my response to it is that is the wrong way of looking at it because if India grows at 5% per year, India’s per capita income is really low and it is far too low to satisfy India’s potential and for India to get people out of poverty.

And which is why India’s case of a 5% growth rate is a big disappointment and specially when you take into account that at the beginning of the year there was an expectation that we will do 9% this year.

A bit conflicted on India

On most countries in the book I was quite categorical. Like I was quite negative on Brazil as you have guessed by now. Even on Russia. I had a fixed view on China. On India I was a bit conflicted. I came out with the book and the most common response here was that are you being a bit pessimistic by giving it a 50% chance. Fine. Six months later by August, the response of most people was that you are being too optimistic on India by giving it a 50% chance of being a breakout nation. So that is how dramatically sentiment has swung on India this year. We went from euphoria on a straight line extrapolation. And how great we are. And how are going to concur the world.

And then there was complete disappointment by August. Last couple of months sentiment has shifted back again. The needle has shifted again. The good news is that expectations are much lower now for India to be a breakout nation.

Indian democracy versus authoritarian China

Gone is the story that how we are going to be the next China out there. One thing I find do disturbing is that a lot of people respond to this by saying you know the reason India cannot be the next China is because we are democracy. And that is the price we pay for being a democracy. China is a authoritarian state. It can implement reforms the way it wants. It can displace people and acquire land. It can set projects up.

India is a democracy therefore we have to pay a price by accepting a lower growth rate. And this argument irritates me. If you look at the high growth instances of the last thirty years, a high growth instance is a situation when a country is able to grow at 5% per year or more in any particular decade. And there are hardly 120 such cases over the last 30 years. How many of them were democracies and how many of them were authoritarian? Its a 50: 50.

For every successful China following an authoritarian regime, there are failures like Vietnam, which was built as the next China, and which has turned out to be a real disappointment, following the authoritarian system. A whole bunch of countries in Africa including the dictatorship of Zimbabwe have failed.

So what matters is the quality of economic leadership and not whether you are democratic or authoritarian. A lot of democracies have done well over the last twenty thirty years. Democracy lets remember is a relatively new concept in much of the emerging world and that is something that we should celebrate.

India is 28 countries with almost distinct identities

There are some state leaders in India who are able to do quite well because they are focussed much more on economic growth. And that to me is a real positive about India as to how India is emerging as a land of 28 independent states, almost 28 countries with distinct identities. We have many good state leaders and the relationship between economic growth and getting re-elected is increasing.

If you manage to grow above the national average and at a past faster than the preceding five years the chances that you as a state leader will get re-elected are extremely high. I think that’s the big message. So therefore you get states like Gujarat where you keep getting victories and then you get a state like West Bengal where you finally get defeated after a very poor performance. This is being backed by data over the last five years.

The picture for India for me is still one that is mixed. But it is improving and improving principally because our expectations have been balanced compared to where we were at the start of this decade. Gone is the era of straight line extrapolations. India still has a reasonable shot at being a breakout nation. But if we got to do it we got to do it state by state. This really is a land of 28 countries like no other emerging market I know. For example China is a very homogeneous society where as India is a lot more heterogeneous. And this bottom up model of economic growth state by state gives up the best hope.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on December 11, 2012.

Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected]

Downgrade fuss's overdone. Who cares?

India’s fiscal deficit has reached worrying proportions. During the first six months of the year it had already crossed 65% of the year’s target of Rs 5,13,590 crore. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

The government’s effort to raise revenues has barely gone anywhere. During the half of the year only 40% of the targeted revenues had been raised. The recent 2G auction was a damp squib and the disinvestment process has barely started.

So what is the way out? “You know you always find some way out. Nobody quite believes the fiscal targets as yet. It is still all about hope and let’s see what happens in the next few months,” says Ruchir Sharma, the head of Emerging Market Equities and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “Only thing that which makes me sound a bit positive in terms of hope that at least they have recognised the problem. Till a year ago, even till April, there was no recognition of the problem. And that to me is at least a positive that we can look on.”

Given the slackening finances of the Indian government there has been a lot of talk about the rating agencies downgrading India, something, if media reports are to be believed, even the finance minister P Chidambaram is worried about.

But Sharma feels the threat is majorly overblown. “I just feel this fuss about that is really overdone to be honest with you because who cares! They (the rating agencies) are far behind, so whether we get downgraded or not, to me it just doesn’t matter and that doesn’t change anything for us,” says Sharma.

Explaining his logic Sharma says “Let me put it this way. If growth is less than 5% etc, that would be horrendous. But I think the reasons for the downgrade are already well telegraphed. If it happens it will be a formality. It will be a short term negative undoubtedly.”

The other big worry in India right now is inflation. “Commodity prices are generally down globally and that should help inflation. The problem is the same that unless we put an end to this populist surge in terms of spending you can’t get a meaningful decline in interest rates,” says Sharma.

“That really is at the core of the problem as far as inflation and interest rates are concerned. How do you put an end to that culture? That genie is out of the bottle. How do you put it back in?,” he asks.

The main problem that remains for inflation is just that there is too much government spending going on and too much of it is inefficient, feels Sharma. “This at a margin is a problem that is getting better,” he adds.

But the real test for the government would be whether they are able to put off the food subsidy kind of schemes. As Sharma puts it “To me the real signal will come if they back down on these populist schemes. Such as the whole food subsidy bill etc. The real fear that I have now is that we do all this now and this is only preparing for another populist scheme at the end of it, at the first sign when things are manageable or things are brought under some control. The fact that they can postpone such things or put them completely away will be a very positive sign. But until then I don’t know.”

The realisation that needs to come in is that government spending as a share of India’s gross domestic product is too high. “You can’t carry on this way. Not because it’s bad thing to do but you can’t keep writing cheques which the exchequer can’t cash. To me that is the bottomline. That spending now for a country of India’s per capita income level of $1500, government spending as a share of GDP is too high.”

Government scams have also been a major issue in the recent past. Sharma feels that this does impact India’s perception in the West. “For them it reinforces the fact about two issues that they have had with India. One is the fact that it is a tough place to do business in. And that shows up in all the metrics like the ease of doing business that World Bank and IMF put out, India ranks in the bottom quartile of most of these things. It also highlights that in India it is very difficult to do greenfield projects and set something up. You might as well be a partner with one of these guys who can get stuff done in India,” says Sharma. “But this is something that people have known and this just reinforces their perception,” he adds.

The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on December 3, 2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

The murky motivations behind Cong’s love of cash transfers

“Sixkku appuram seven da, Sivajikku appuram yevenda,” says Superstar Rajinikanth in the tremendously entertaining Sivaji – The Boss. The line basically means that “after six there is seven, after Sivaji there is no one.”

Like there is no one after Sivaji (or should we say the one and only Rajinikanth) similarly there is no one in the Congress party beyond the Gandhi family. And the party can go to any extent to keep the family going and at the centre of it all.

Take the recent decision of the Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government to implement the direct cash transfers scheme in a hurry. On the face of it one cannot really question the good logic behind the scheme. The idea is to make cash transfers directly into the accounts of the citizens of this country instead of offering them subsidies, as has been the case until now. This transfer will happen through Aadhar unique ID card enabled banks accounts.

As The Hindu reports quoting the finance minister P Chidambaram “Initially, 29 welfare programmes — largely related to scholarships and pensions for the old, disabled — operated by different ministries will be transferred through Aadhaar-enabled bank accounts in 51 districts spread over 16 States from January 1, and by the end of the next year it should cover the entire country, Mr. Chidambaram said. He added that only at a later stage would the government consider the feasibility of cash instead of food (under the Public Distribution System) and fertilizers, since it was more complicated.”

So far so good.

But the question is why is the government in such a hurry to implement the scheme? The scheme is to be implemented in 51 districts January 1, 2013 and eighteen states by April 1, 2013, the start of the next financial year. The government hopes to implement the scheme in the entire country by the end of 2013 or early 2014.

A scheme of such high ambition first needs to be properly tested and only then fully implemented. As has been explained in this earlier piece on this website there have been issues with the government’s other cash transfer programme, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS).

There have also been issues with pilot projects that have been carried on the cash transfers scheme till now. In one particular case people who got the subsidy had to spend a greater amount of money than the subsidy they received, in getting to the bank and collecting their subsidy.

The other big issue that might come up here is the opening of bank accounts. While the Aadhar Card does identify every person uniquely, India remains a terribly under-banked country. And that is something that needs to be set right in a very short period of time, if the direct cash transfers system needs to get anywhere.

The big selling point of the direct cash transfers scheme is that leakages which happen from the current system of subsidies will be eliminated. For example, currently a lot of kerosene sold through the subsidised route does not reach the end user and is sold in the open market where it is also used to adulterate petrol and diesel, among other things. Some of this kerosene also gets smuggled into the neighbouring countries where kerosene is not as cheap as it is in India and hence there is money to be made by buying kerosene cheaply in India and selling it at a higher price there.

Now people will buy kerosene at its market price and the subsidy will come directly into their bank accounts. So the subsidy will reach the people it is supposed to reach and will not enrich those people who run the current system.

While this sounds very good on paper, the reality might turn out to be completely different as an earlier piece on this website explains and the so called leakages might continue to take place.

Hence, its very important to run pilot tests in various parts of the country, solicit feedback, implement the necessary changes and then gradually go for a full fledged launch. A system of such gigantic proportion cannot be built overnight as the government is trying to.

So that brings us back to the question why is the government in such a hurry to implement direct cash transfers scheme? And in a way screw up what is inherently a good idea.

The answer probably lies in what Jairam Ramesh, the Union Rural Development Minister told The Hindu ““The Congress is a political party, not an NGO. We had promised cash transfer of benefits and subsidies in our election manifesto of 2009,” Mr. Ramesh said, asking “Where is the talk of elections?””

But as the great line from the great political satire Yes Minister produced by the BBC goes “The first rule of politics: never believe anything until it’s been officially denied.” So this hurry to get the scheme going is nothing but the Congress party getting ready for the 2014 Lok Sabha polls.

As an article in the India Today magazine points out “The government’s calculation is that just as the National Rural Guarantee Act and the farmer loan waiver had sealed its victory the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, the direct cash transfer of subsidies would do the same in the 2014.”

Or as Ramesh put it more aptly by getting into the poll mode “aapka paisa, aapke haath“. And this is being done to ensure that the Congress party does well in the next Lok Sabha elections and Rahul Gandhi becomes the prime minister of India.

There are several interesting points that arise here. The first point is that the launch of the cash transfers system will give the Congress politicians battling a string of corruption charges something new to talk about. And that is important.

Indira Gandhi established by winning the 1971 Lok Sabha with her Garibi Hatao slogan that it is important to talk about the right things in the run up to the elections irrespective of the fact whether anything concrete about it is done or not, in the days to come.

There is no one more cunning as a political strategist this country has had than Mrs Gandhi. And every Congressman worth his salt knows that. It is more important to make the right noises than come up with results.

The second point that comes out here is that the government is making all the right noises about this scheme being fiscally neutral. This means that the expenditure on

subsidies won’t go up. Only the current subsidies on offer will now be distributed through this route. This is something that I am unwilling to buy.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the right to food act is set in place in the days to come before the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. The excuse will be that now that we have a direct cash transfer set up in place we are well placed to launch the right to food act as there will be no leakages.

While the idea behind subsidies is a noble one, the government of India is not in a position to foot the mounting bills. The fiscal deficit for the year 2012-2013 has been targeted at Rs 5,13,590 crore or 5.1% of the gross domestic product. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends.

As the Kelkar committee on fiscal consolidation recently pointed out “A careful analysis of the trends in the current year, 2012-13, suggests a likely fiscal deficit of around 6.1 percent which is far higher than the budget estimate of 5.1 percent of GDP, if immediate mid-year corrective actions are not taken.” The committee estimated if the government continued to function as it currently is it will end up with a fiscal deficit of Rs 6,15,717 crore. And I believe that the Kelkar committee’s estimates are fairly conservative. So we might very end up with a higher fiscal deficit if the direct cash transfers system is used to launch more subsidy programmes as I guess would be the case.

And that brings me to my third point. As the India Today magazine points out “The cash transfer of subsidies estimated to be worth Rs 3,20,000 crore will not be an easy task. Procedurally, one of the major obstacles would be the fact that many of the beneficiaries might not even have bank accounts. But more significantly, the scheme does nothing to address the main problem – bring down the subsidies to ease the pressure on the exchequer.”

High subsidies basically imply greater borrowing by the government. This in turn means lesser amount of money being available for others to borrow and hence higher interest rates. Higher subsidy also means more money in the hands of Indian citizens. This more money will chase the same number of goods and services and hence lead to higher inflation. Also be prepared for a higher food inflation in the years to come.

Higher interest rates will mean that the lower economic growth will continue in the time to come despite of what the politicians and the bureaucrats would like us to believe. Consumers will take on lesser debt to buy homes, cars and consumer goods. This will be bad for business, and in turn they will go slow on their expansion plans and thus impact economic growth further.

As Ruchir Sharma writes in his bestselling book Breakout Nations. “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period…If the government continues down this path India, may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

And that’s the cost this country will have to take on a for one party’s love for a family. To conclude, let me quote something that Ramchandra Guha writes in the essay Verdicts on Nehru which is a part of his latest book Patriots and Partisans “Mrs (Indira) Gandhi converted the Indian National Congress into a family business. She first brought in her son Sanjay, and after his death, his brother Rajiv. In each case, it was made clear that the son would succeed Mrs Gandhi as head of Congress and head of government.”

The sudden hurry to implement the direct cash transfers system probably tells us that this generation’s Mrs Gandhi has also made it clear to Congressmen that her son is ready to take over the reins of this country.

Hence, the Congress government is now working towards making that possible. In the process India might get into huge trouble. But we will still have Rahul Gandhi as the Prime Minister.

And that is more important for Congressmen right now than anything else.

The article was originally published on www.firstpost.com on November 29,2012.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])