Today is the first day of the new financial year. And banks still haven’t cut interest rates. This despite the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) of cutting the repo rate twice by 50 basis points (one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage) between January and March 2015. Repo rate is the rate at which RBI lends to banks and acts as a sort of a benchmark to the interest rates that banks pay for their deposits and in turn charge on their loans.

Other than the RBI cutting the repo rate, the finance minister has also been very vocal about the entire issue. On March 22, 2015, he remarked: “We do not put pressure on them (i.e. public sector banks) We only expect and our expectations come true.”

A few days later on March 25 2015, Jaitley said: “I mentioned a few days ago in the presence of the (RBI) Governor (Raghuram Rajan) that we do not pressurise the banks to cut rates. But we do expect the banks after assessing the situation to act in a prudent manner. Our banks have been by and large responsible. And I am quite certain we will see more cuts in future.”

Despite this overt pressure, the banks haven’t gone around cutting the interest rates on their loans. A recent Bloomberg newsreport pointed out that 43 out of the 47 scheduled commercial banks haven’t cut their base rates or the minimum interest rate a bank charges its customers.

Unless, banks cut their base rate there is no point in the RBI cutting the repo rate simply because the borrowers as well as the prospective borrowers do not benefit from lower interest rates. Having said that, just because the RBI has cut the repo rate or the fact that the finance minister thinks interest rates should be lower, doesn’t mean that banks should lower interest rates. One thing that they need to look at is their deposit growth vis a vis their loan growth. Latest data from the RBI suggests that deposit growth over the last one year was at 11.6%. In comparison, the loan growth of banks was at 10.2%. Also, the deposit growth was on a higher base. Hence, it is safe to say that deposits of banks have grown much faster than their loans.

This conclusion can also be made by calculating the incremental credit deposit ratio. The incremental credit deposit ratio over the last one year stands at 67.3%. This means that for every Rs 100 raised as deposit, banks have given out loans worth Rs 67.3. Ideally, banks should be lending around Rs 74.5 for every Rs 100 they raise as a deposit. This, after adjusting for the Rs 25.5 of Rs 100 that they need to maintain as cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio.

Around this time last year, the incremental credit deposit ratio had stood at 73.7%. Hence, what this clearly tells us is that lending by banks is growing at a significantly slower pace in comparison to the increase in deposits. Given this, banks should be in a position to cut their base rate, but they still haven’t.

Why? While banks are quick to raise interest rates when the RBI raises the repo rate, they are slow to cut interest rates when the RBI cuts the repo rate. Also, if banks lower their base rate, the interest they earn on the money that they have lent comes down immediately. But the interest that they pay on their deposits does not change. While loans rate are floating, deposit rates are not. Hence, banks continue to hold on to interest rates on their loans.

As a March 11 report by the International Monetary Fund on India points out: “Pass-through to deposit and lending rates is relatively slow and the deposit rate adjusts more quickly to monetary policy changes than does the lending rate.” What this means is that after the RBI cuts the repo rate, banks tend to cut their deposit rates more quickly in comparison to their lending rates. Further, it takes around 9.5 months for deposit rates to change and 18.8 months for the lending rates to change,after the RBI has cut the repo rate, the IMF stated. Given this, it will be a while by the time banks start to cut their lending rates. And this assuming that the RBI does not change its direction on repo rate cuts.

What has not helped is the fact that banks continue to accumulate bad loans. As the IMF report on India points out: “Evidence of corporate India’s worsening financial performance is found in the rising share of stressed loans in banks’ portfolios—both non-performing assets (NPAs) and restructured loans have continued to increase, and are at their highest levels since 2003…Corporates in the manufacturing and construction sectors, plus the infrastructure sector, contributed notably to banks’ non performing assets. Between 2002/03 and 2013/14 corporate debt increased by 428 percent for a sample of 762 firms.”

With such high levels of borrowing the pressure on the balance sheets of banks (in particular public sector banks) is likely to continue in the days to come. As the IMF reports points out: “Some corporates are likely already credit constrained due to high leverage, which in turn continues to put pressure on the health of the financial system, in particular on the balance sheets of public sector banks (PSBs). This will further affect bank risk taking as well as the ability of the banking system to finance economic recovery.”

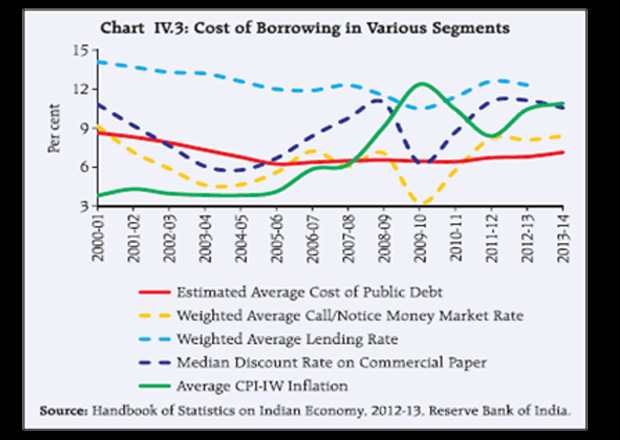

The bad loans will also limit the ability of banks to cut their lending rates. As Crisil Research pointed out in a recent report: “High non performing assets curb the pace at which benefits of lower policy rate are passed on to borrowers. Data shows periods of high NPAs – such as between 2002 and 2004 (when NPAs were at 8.8% of gross advances) – are accompanied by weaker transmission of policy rate cuts. This time around, NPA levels are not as high as witnessed back then, but still remain in the zone of discomfort.”

Given this, the finance minister Jaitley may keep asking banks to cut their lending rates, but the banks are not likely to oblige him any time soon.

The column was originally published on The Daily Reckoning on April 1, 2015