On August 30, 2017, the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) published its annual report. The annual report had data points looking at which we can finally say that demonetisation has not met any of the objectives that it set out to achieve.

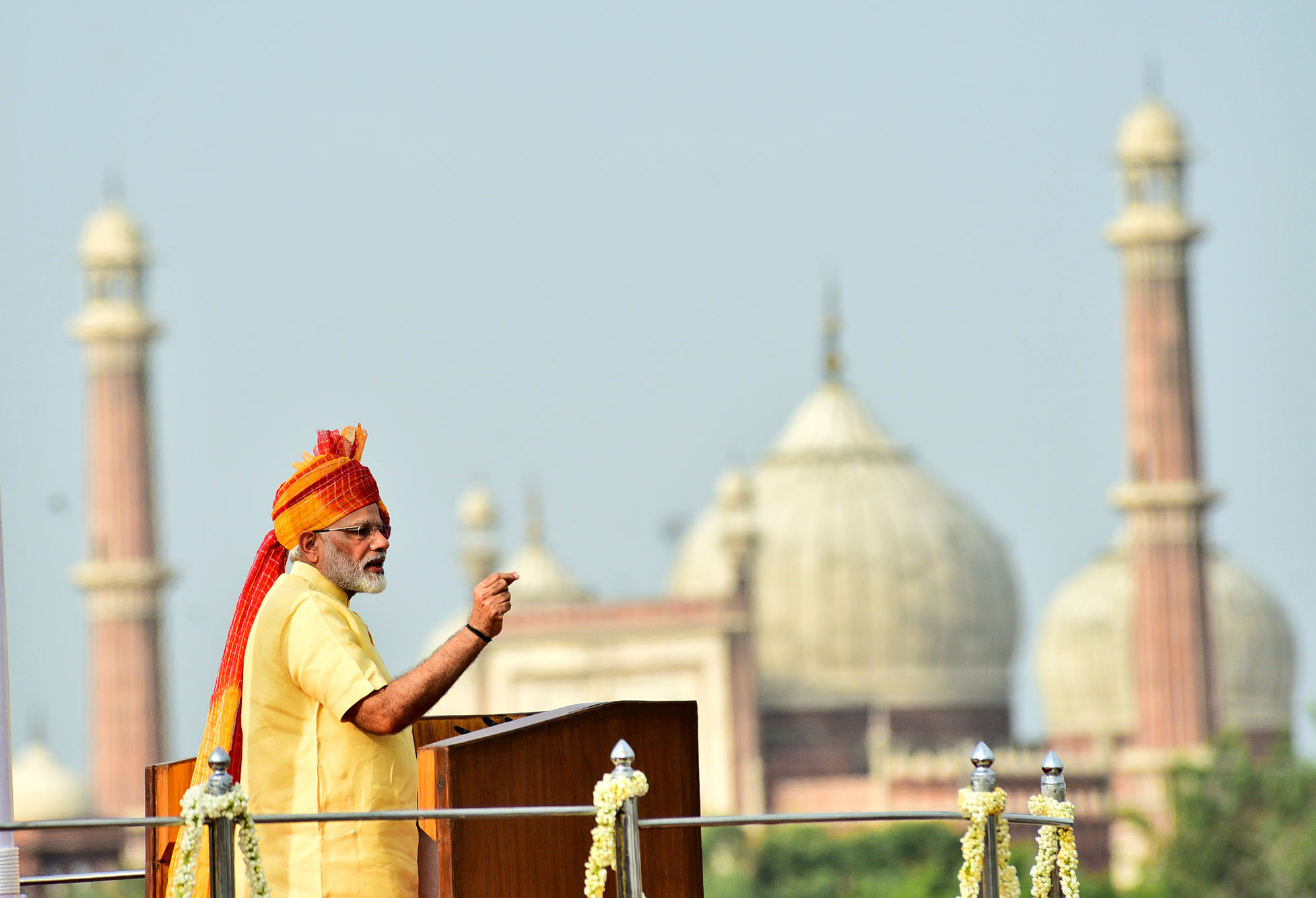

On November 8, 2016, the prime minister Narendra Modi in an address to the nation said that the notes of denomination Rs 500 and Rs 1,000, would not be legal tender from November 9, 2016, onwards. People in possession of these notes could deposit them in banks until December 30, 2016. In value terms notes worth Rs 15.44 lakh crore were demonetised.

As per the press release accompanying the decision to demonetise, there were two aims of demonetisation: 1) Eliminating Black Money which casts a long shadow of parallel economy on our real economy. 2) Eliminating Fake Indian Currency Notes (FICN).

Let’s look at how successful demonetisation has been in achieving these two main goals. The idea was that people who had black money in the form of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000, would not deposit it in the banks for the fear of being identified by the government and in the process black money would be destroyed.

This was a point that was made over and over again by those in favour of demonetisation. As finance minister Arun Jaitley said in an interview: “Obviously people who have used cash for crime purposes are not foolhardy enough to try and risk and bring the cash back into the system because there will be questions asked.”

Niti Aayog Member Bibek Debroy was specific on the proportion of demonetised money that would not come back. As he said in an interview: “Even now, Rs 1.6 lakh crore is what will be missing at the end of it all. Those are the figures. If I take a base of roughly rounding off demonetised currency around Rs 16 lakh crore, 10 per cent of it is about Rs 1.6 lakh crore.” Hence, Debroy felt that currency worth Rs 1.6 lakh crore would not come back and this would lead to the destruction of black money.

The American-Indian economist Jagdish Bhagwati (along with two co-authors) was even more optimistic on this front, and in a column in the Mint newspaper on December 27, 2016, wrote: “Suppose we accept the estimate that one-third of the approximately Rs 15 trillion [Rs 15 lakh crore] in demonetised notes is black money.” These economists did not bother to explain, what logic did they base their assumption on.

The RBI Annual Report on Page 195 says that demonetised notes worth Rs 15.28 lakh crore were deposited into banks, up to June 30, 2017. This basically means that almost 99 per cent of the demonetised money was deposited into banks. Hence, almost all the black money held in the form of cash, also made it back into the banks and wasn’t really destroyed, as had been hoped.

Given this, instead of destroying black money held in the form of cash, demonetisation seems to have become a legal money laundering scheme, where people with black money have found ingenious ways to deposit it into the banking system. So, the first objective of demonetisation of eliminating black money has not been achieved.

Now we are being told that just because the money has been deposited into banks that does not mean it is not black money. And given this, the Income Tax department now has the data and will go after those people who have deposited their black money into banks. So far so good.

Let’s look at the past record of the Income Tax department when it comes to going after people having black money and achieving convictions. Take a look at Table 1.

Table 1: Year wise details of number of cases in which prosecutions were launched by the Income Tax Department.

| Financial Year | No. of cases in which presecutions launched | Cases coumpounded | No. of persons convicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-14 | 641 | 561 | 41 |

| 2014-15 | 669 | 900 | 34 |

| 2015-16 | 552 | 1,019 | 28 |

| 2016-17* | 323 | 404 | 13 |

* Provisional figures upto 31st October, 2016

What does Table 1 tell us? It shows the extremely limited capacity of the Income Tax Department when it comes to bringing tax evaders to book. Even if the Income Tax department improves on these numbers, there isn’t much hope on the tax collection front. The prime minister Narendra Modi in his Independence Day speech said: “More than Rs 2 lakh crore black money has reached banks.” An impression is being created that this money is just waiting to find its way into government coffers. The people who have this black money aren’t exactly stupid. They aren’t waiting to hand it over to the government. They have access to good lawyers and chartered accountants and they know how the Indian system works.

Looking at this, it is safe to say the government is just trying to defend a bad decision and it is highly unlikely that it will earn a significant amount from all this black money.

In fact, the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, the income declaration scheme, launched by the government in the aftermath of demonetisation, failed miserably. The scheme which was launched on December 16, 2016, managed to collect all of Rs 2,300 crore as taxes. This tells us very clearly how much those who have black money fear the taxman in this country.

Now let’s jump to the second issue of eliminating fake currency notes. As far as detecting fake currency is concerned, nothing much seems to have happened on this front. Data from the RBI annual report tells us that the number of fake Rs 500 (old series) and Rs 1,000 notes detected between April 2016 to March 2017 was 5,73,891. The total number of demonetised notes stood at around 2,400 crore. This basically means that as a proportion the fake notes identified between April 2016 to March 2017 stands close to 0 per cent of the demonetised notes.

The total number of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 fake notes detected between April 2015 and March 2016, stood at 4,04,794. And this happened without any demonetisation. Hence, demonetisation has failed on its two major objectives.

Now let’s look at the third objective of demonetisation. In the original scheme of things increasing cashless transactions wasn’t on the table at all. It came into the scheme of things once prime minister Modi talked about it in the Mann ki Baat programme on radio on November 27, 2016, where he said: “The great task that the country wants to accomplish today is the realisation of our dream of a ‘Cashless Society’. It is true that a hundred percent cashless society is not possible. But why should India not make a beginning in creating a ‘less-cash society’? Once we embark on our journey to create a ‘less-cash society’, the goal of ‘cashless society’ will not remain very far.”

How have we done on this front? Let’s take a look at Figure 1 and Figure 2. These figures plot the total number of cashless transactions through the years in terms of volume (i.e. number) and value of the transactions. I have ignored the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) mode of transferring money because it can be used only for transactions of Rs 2 lakh and over. Hence, it clearly does not fall in the retail domain.

Figure 1:

What does Figure 1 tell us? It tells us very clearly that the total number of cashless transactions rose in the aftermath of demonetisation. They have fallen since then and are now more or less back on the trend growth line (i.e. the red line in Figure 1). The trend growth line has been plotted in order to take care of the fact that cashless transactions had been growing anyway, irrespective of demonetisation.

In fact, between March 2017 when cashless transactions peaked and June 2017, the total number of cashless transactions have fallen by 10.1 per cent.

Now take a look at Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Figure 2 clearly tells us that the total value of cashless transactions is now below the trend line. As former RBI governor said in a recent interview: “If you look at electronic transactions, you see that there was a blip-up when demonetisation happened but it has come back to broadly the trend growth line.”

One form of cashless payments which has seen good growth is the United Payment Interface. But it forms just 0.6 per cent of the overall cashless transactions and it will be a while before it forms a substantial portion.

Given this, the 2+1 original aims of demonetisation have flopped. The data clearly shows us that.

Of course, we are now being told of new benefits of demonetisation. Take the case of the number of returns being filed going up. Very true. But has it led to increased tax collections? A press release put out by the ministry of finance on August 9, 2017, states the following: “The Direct Tax collections up to July,2017[i.e. between April 2017 and July 2017] in the Current Financial Year 2017-18 continue to register steady growth. Direct Tax collection during the said period, net of refunds, stands at Rs. 1.90 lakh crore which is 19.1% higher than the net collections for the corresponding period of last year.”

Basically, direct tax collections have grown by 19.1 per cent during the first four months of this financial year in comparison to the same period in the last financial year. Hence, has demonetisation led to an increase in the growth of collection of direct taxes?

A press release put out by the ministry of finance on August 9, 2016, had this to say: “The figures for direct tax collections up to July, 2016 show that net revenue collections are at Rs.1.59 lakh crore which is 24.01% more than the net collections for the corresponding period last year.”

Hence, in the period between April to July 2016, the direct tax collections had grown by 24 per cent, without the demonetisation of currency which was carried out in November 2016. What this tells us is that direct tax collections grew faster before demonetisation than they are growing after demonetisation.

Personal income tax collections have grown by 15.7 per cent during the first four months of this financial year. They had grown by 46.6 per cent during the first four months of the previous financial year. So much for increase in taxes collected.

What this tells us is that demonetisation has slowed down the economy and given that the growth in direct taxes has slowed down as well.

Another point being made is that with all the money coming into the banking system, the interest rates have come down. Yes, they have. But has it led to increased lending, is a question no one is asking. Between the end of October 2016 and the end of July 2017, the total non-food lending carried out by banks stood at Rs 2,75,690 crore. The total non-food lending carried out by banks between end of October 2015 and the end of July 2016 had stood at Rs 3,43,013 crore. Hence, bank lending after demonetisation has fallen by close to 20 per cent, if we were to compare it to a similar period in the years gone by.

This is a point that I keep making. People and companies borrow when they are in a position to repay and not simply because interest rates are down. Demonetisation has had a negative impact on the ability of people to repay loans.

Another point that needs to be made here is that 62 per cent of household financial savings in India are invested in deposits. A fall in interest rates hurts people who invest in deposits. This includes senior citizens who use fixed deposits a generate a monthly income. It also includes people saving for the future for their wedding and education of their children. These people are many more in number than borrowers. With lower interest rates, they have to cut down on their current consumption expenditure. This hurts overall economic growth.

Demonetisation has also slowed down on overall economic growth. Take a look at Figure 3. It plots the GDP growth rate of India since March 2016.

Figure 3:

As can be seen from Figure 3, the GDP growth rate between July and September 2016 had stood at 7.53 per cent. This was before demonetisation was announced in November 2016. It has since fallen to 5.72 per cent. This is clearly an impact of demonetisation. As Rajan said in an interview: “Let us not mince words about it – GDP has suffered. The estimates I have seen range from 1 to 2 percentage points, and that’s a lot of money – over Rs 2 lakh crore and maybe approaching Rs 2.5 lakh crore.”

He points out other costs as well: “The hassle cost of people standing in line, the printing cost that the RBI says is close to Rs 8,000 crore, the cost to the banks of withdrawing the money, and the time spent by their clerks, by their managers and by their senior officers doing all this, and the interest being paid on all those deposits, which earlier were effectively an interest-free loan to the RBI.”

An argument is being made that in the period April to June 2017 the growth fell because of the Goods and Services Tax which was supposed to be introduced on July 1, 2017. That is really not true. (you can read about it in detail here).

Also, even this fall in growth may not capture the situation completely given that the informal sector suffered the most because of demonetisation, and the GDP calculation does not capture that well enough.

All in all, demonetisation was a massive flop. It was an act of self-destruction that has hurt the Indian economy majorly and put us back by at least 1.5 to two years, on the economic growth front. This is something that India can ill-afford given the fact that 1.2 crore youth are entering the workforce every year.

Why I continue to write about demonetisation

People have been telling me the real aim of demonetisation was political, so why am I going on and on about the economic impacts.

I am not a dolt I understand that.

The subject of economics before it got hijacked by mathematicians was called political economy. The only place where economics and politics are different things are in an economics classroom or an economics textbook.

Hence, all political moves have economic impacts and vice versa, irrespective of what politicians and economists like to believe.

Also, will demonetisation negatively impact the Modi government, is a question I am being asked. I don’t know. But it has been a huge negative for the Indian economy, a problem which in the normal scheme of things, we wouldn’t have had to deal with.

And given that it needs to be highlighted and talked about, irrespective of whether it has made Modi politically stronger or weaker. That only time will tell. So, keep watching this space.

To conclude, I am a full-time writer and I am paid to write. I can’t do anything else. This is an honest way to make a living. So, I write.

The column was originally published on Equitymaster on September 4, 2017.