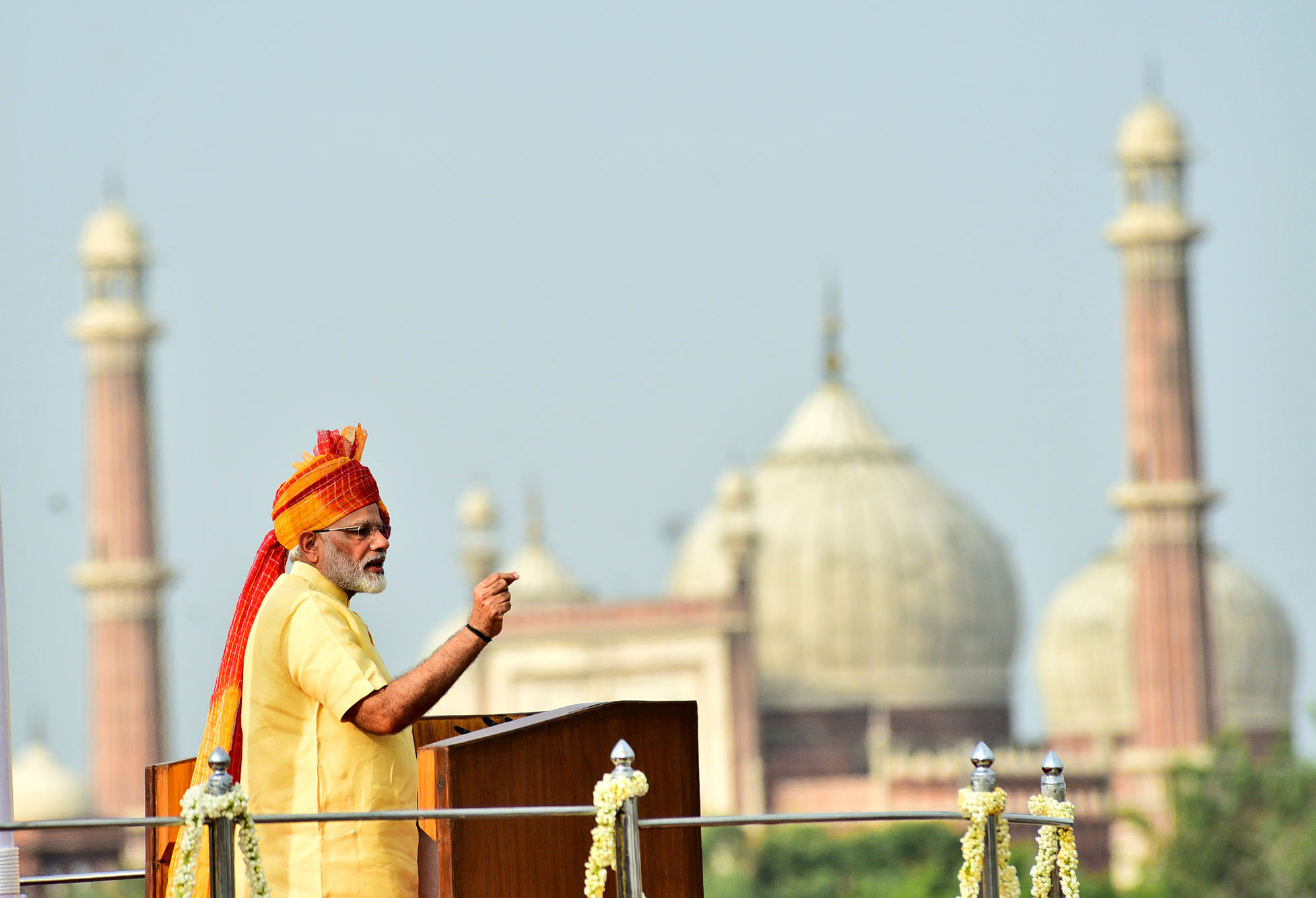

The prime minister Narendra Modi in his Independence Day speech made last week said: “The Government has launched several new initiatives in the employment related schemes and also in the manner in which the training is imparted for the development of human resource according to the needs of the 21st century. We have launched a massive program to provide collateral free loans to the youth. Our youth should become independent, he should get the employment, he should become the provider of employment. Over the past three years, ‘Pradhanmantri Mudra Yojana’ has led to millions and millions of youth becoming self-dependent. It’s not just that, one youth is providing employment to one, two or three more people.”

Adding to this, the Bhartiya Janata Party president Amit Shah recently said: “the youth have turned into job-creators from job-seekers“. Dear Reader, I would request you to keep these points in your head, while I set the overall context of this piece. As I have written on several previous occasions in the past, one million Indians enter the workforce every month. That makes it 1.2 crore Indians a year. There is not enough work going around for all these young individuals entering the workforce every year.

While, it is not possible for the government to create jobs for such a huge number of people, it is possible that the government makes it easier for the private sector to create jobs. (I will not go into this, simply because this is a separate topic in itself and I guess I will deal with this on some other occasion).

Take a look at Table 1. This is a table that I have used on previous occasions as well. But I need to repeat it, in order to set the context for this piece.

Table 1: Percentage distribution of persons available for 12 months

What does Table 1 tell us? It tells us that only 60.6 per cent of the individuals who were looking for work all through the year, were able to find it. This basically means that nearly 40 out of every 100 Indians who are a part of the workforce and were looking for work all through the year, could not find regular work. In rural India, around half of the workforce wasn’t able to find regular work through the year.

This table is at the heart of India’s unemployment problem. Actually, we do not have an unemployment problem, what we have is an underemployment problem. There isn’t enough work going from everyone who joins the workforce. The solution that prime minister Narendra Modi has to this is that India’s youth should become self-dependent and seek self-employment. In the era of post-truth, this sounds like a terrific idea. But this is nothing more than marketing spin.

Let’s look at some data on this front. As the Report on the Fifth Annual Employment-Unemployment Survey, 2016, points out: “At the All India level, 46.6 per cent of the workers were found to be self-employed… followed by 32.8 per cent as casual labour. Only 17 per cent of the employed persons were wage/salary earners and the rest 3.7 per cent were contract workers.”

The point being that nearly half of India’s workforce is already self-employed. And they aren’t doing well in comparison to those who have regular jobs. Take a look at Table 2.

Table 2: Self-employed/Regular wage salaried/Contract/Casual Workers

according to Average Monthly Earnings (in %)

What does Table 2 tell us? It tells us very clearly that self-employment is not as well-paying as a regular salaried job is. As is clear from the table nearly two-thirds of the self-employed make up to Rs 7,500 per month. In case of the regular salaried lot this is at a little over 38 per cent. Clearly, those with regular jobs make much more money on an average.

Further, only 4 per cent of the self-employed make Rs 20,000 or more during the course of a month. In comparison, more than 19 per cent of individuals with jobs make Rs 20,000 or more during the course of a month.

What Table 1 and Table 2 tell us is that India’s youth have already taken to being self-employed. Hence, there is nothing new in Narendra Modi’s idea. Further, it is clearly not working.

As Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo write in Poor Economics: “The sheer number of business owners among the poor is impressive. After all, everything seems to militate against the poor being entrepreneurs. They have less capital of their own (almost by definition) and… little access to formal insurance, banks and other sources of inexpensive finance…. Another characteristic of the businesses of the poor and the near-poor is that, on average, they are not making much money.”

The point here is that a large part of the workforce is not self-employed by choice but are self-employed because they have no other option. Banerjee and Duflo call them ‘reluctant entrepreneurs’. The phrase summarises the situation very well.

Other than the reluctant entrepreneurs, more than 30 per cent of the workforce comprises casual labourers, who seek employment on an almost daily basis. The reluctant entrepreneurs and casual labourers looking for daily work essentially tell us that no one can really afford to stay unemployed.

Hence, the problem is not a lack of employment but a lack of employment which is productive enough.

Prime minister Modi talked about his government launching, “several new initiatives in the employment related schemes and also in the manner in which the training is imparted for the development of human resource according to the needs of the 21st century.”

How good does the data look on this front? As the Volume 2 of the Economic Survey of 2016-2017 points out: “For urban poor, Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAYNULM) imparts skill training for self and wage-employment through setting up self-employment ventures by providing credit at subsidized rates of interest. The government has now expanded the scope of DAY-NULM from 790 cities to 4,041 statutory towns in the country. So far, 8,37,764 beneficiaries have been skill-trained [and] 4,27,470 persons have been given employment.”

The annual report of 2016-2017 of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship of the government of India makes an estimate about the number of people trained by different ministries during the course of the financial year. For the period April to December 2016, the number is at around 19.59 lakh. The annual target was set at 99.35 lakh. Given this, the gap between the target set and the target achieved is huge.

Another way of looking at this is that 1.2 crore Indians are entering the workforce every year. They have had an average education of around five years (i.e. they have passed primary school). Given this, they really don’t have any work-related skillset. At best, they can add and subtract, and perhaps read a little.

Hence, they need to be trained or there need to be enough low skill jobs going around. Real estate and construction, the two sectors that can create these kind of jobs, are in a huge mess. This is something that can be sorted, but in order to do that some serious decisions on black money need to made. This includes cleaning up of political funding and the change in land usage regulations at state government level.

Take a look at the following graphic (Figure 1) reproduced from the annual report of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship.

Figure 1:

What Figure 1 tells us very clearly is that the scale that is needed to train people is simply not there. And this will lead to a substantial chunk of individuals entering the workforce looking for low end self-employment opportunities anyway, as has been the case in the past. Or people will continue to stick to agriculture.

Prime Minister Modi in his speech further said: “Over the past three years, ‘Pradhanmantri Mudra Yojana’ has led to millions and millions of youth becoming self-dependent. It’s not just that, one youth is providing employment to one, two or three more people.”

Let’s look at this statement in some detail. Between April 2015 and August 11, 2017, the government gave out Mudra (Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Bank) loans worth Rs 3.63 lakh crore to 8.7 crore individuals. This works out to an average loan of around Rs 41,724. There is no evidence until now whether this is working or not. Can a loan of a little under Rs 42,000 provide employment to one, two or three more people, is a question which hasn’t been answered up until now.

The CEO of Mudra was asked by NDTV recently, as to how many jobs had the Mudra loans created. He said: “We are yet to make an assessment on that… We don’t have a number right now, but I understand that NITI Aayog is making an effort to do that.”Given this, Mudra loans making millions of youth self-dependent is presently nothing more than something that prime minister Modi likes to believe in.

While he is entitled to his beliefs, I would like to look at some data before concluding that Mudra loans are the answer to India’s job crisis.

The column was originally published on Equitymaster on August 21, 2017.