Lawyers who become politicians are extremely eloquent speakers. But do they ‘really’ mean what they say? Or is it just something that sounds good at a given point of time, like a film dialogue?

The finance minister Arun Jaitley in his maiden budget speech in July 2014 had said: “We need to introduce fiscal prudence that will lead to fiscal consolidation and discipline. Fiscal prudence to me is of paramount importance because of considerations of inter-generational equity. We cannot leave behind a legacy of debt for our future generations. We cannot go on spending today which would be financed by taxation at a future date.”

Most governments spend more than what they earn. In order to bridge the gap, they borrow money by selling governments bonds. These bonds are repaid in the years to come. If the government borrows more today, the more it has to repay in the years to come.

This repayment is carried out of the money the government earns from taxing the future generations. This means that the benefits of borrowing are received by one generation but the debt is repaid by another. And this is why Jaitley talked about “considerations of inter-generational equity”. Or so it seemed.

The only way of respecting inter-generational equity is to borrow less today, so that the future generations don’t have to repay it, in the days to come. Borrowing less is only possible if the government is spending less today.

In his July 2014 budget speech Jaitley had talked about precisely this. He had said: “Difficult, as it may appear, I have decided to accept this target as a challenge. One fails only when one stops trying. My Road map for fiscal consolidation is a fiscal deficit of 3.6 per cent [of the gross domestic product (GDP)] for 2015-16 and 3 per cent for 2016-17.”

Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends. This difference is made up through borrowing money by selling government bonds. Hence, a lower fiscal deficit means lower borrowing and in the process the “considerations of inter-generational” equity is take into account.

In the budget speech Jaitley made in February 2015, the considerations of inter-generational equity took a slight backseat. He postponed the achievement of the fiscal deficit target of 3% of the GDP for 2016-2017, by a year.

As he said on that occasion: “Rushing into, or insisting on, a pre-set time-table for fiscal consolidation pro-cyclically would, in my opinion, not be pro-growth. With the economy improving, the pressure for accelerated fiscal consolidation too has decreased. In these circumstances, I will complete the journey to a fiscal deficit of 3% in 3 years, rather than the two years envisaged previously. Thus, for the next three years, my targets are: 3.9%, for 2015-16; 3.5% for 2016-17; and, 3.0% for 2017-18. The additional fiscal space will go towards funding infrastructure investment.”

What the government had set out to achieve in a period of two financial years, Jaitley said would now be achieved in three years. This was in February 2015, when the budget for the current financial year 2015-2016 was presented.

In the recent past, there have been news-reports as well as statements which suggest that the government will again postpone, the fiscal deficit targets it had set for itself. “I am not particularly worried about the fiscal deficit target,” Jaitley said in early December.

A Reuters news-report quotes a senior finance ministry official as saying that the “the minister[i.e. Jaitley] has been advised to increase its fiscal deficit target to 3.7 or 3.9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) from 3.5 per cent.” “The economy is still suffering from slack demand…It needs a conducive fiscal and monetary policy,” the official added.

The industrial as well as consumer demand are seeing slow-growth and hence the government should be spending more, and in the process incurring a higher expenditure and a higher fiscal deficit. The higher government expenditure will push up economic growth. This is what the senior finance ministry official meant.

This is something Jaitley has also said recently: “Public investment has been stepped up in the last year and it will continue to remain stepped up… When you fight a global slowdown, public investment has to lead the way.”

In a year when the government will have to incur significantly extra expenditure to implement the recommendations of the Seventh Pay Commission, implement one rank one pension for the armed forces and pay pending, fertilizer and food subsidies, where is the money for public investment going to come from?

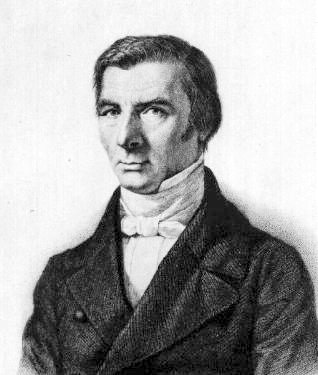

It is worth recounting here what the French economist Frédéric Bastiat had said in his 1874 book That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen. “In the department of economy, an act, a habit, an institution, a law, gives birth not only to an effect, but to a series of effects. Of these effects, the first only is immediate; it manifests itself simultaneously with its cause–it is seen. The others unfold in succession—they are not seen. It is well for us if they are foreseen.”

When we talk about the government abandoning the fiscal deficit target and spending more, this is precisely how things are playing out. The immediate effect or that which is seen is that higher government expenditure will create economic growth in an environment where industrial and consumer demand growth continues to remain slow. This is the effect that is being ‘seen’.

But there are other effects which are not being seen. The entire issue about inter-generational equity that Jaitley had talked about in his July 2014, seems to have taken a backseat.

Let’s go back a few years in order to understand this point. In 2008-2009, the government spent 51% of what it earned in paying interest on its existing debt and repaying the debt that was maturing. In the aftermath of the financial crisis that started in September 2008, the government increased its expenditure and its fiscal deficit. When the government talked about increased government spending it was only in the context of economic growth. This effect was seen.

Nevertheless, increased government spending meant more borrowing. In 2015-2016, the government will spend around 60% of what it earns in paying interest on existing debt and repaying the debt that matures. The higher borrowing of 2008-2009 and the years that followed is now having an impact. This was the effect which was unseen or wasn’t foreseen in 2008-2009, when the government decided to spend more. This is what Jaitley meant when he talked about considerations of inter-generational equity.

When one government borrows more it leaves a problem for another government in years to come. Also, as more money goes towards debt servicing it leaves little money for other things, unless more money is borrowed.

Further, the government doesn’t have any separate access to borrowings. As economist M Govinda Rao wrote in a recent column in The Financial Express: “This year, the Union government’s deficit is set at 3.9%, and with the states together having a deficit of about 2.2%, the aggregate fiscal deficit of the government works out to 6.1%. It is reported that 21 distribution companies are likely to join the UDAY scheme and the deficit on that account could be about 1%.” If we were to add all this the real fiscal deficit of the government would come at 7.1% of the GDP. The household financial savings in 2014-2015 stood at 7.5% of GDP.

This means that if the government borrows more it will automatically lead to higher interest rates for everyone else who wants to borrow. When the finance minister talks about public investment and not being bothered about a higher fiscal deficit, these points also need to be ‘seen’. Currently, they are not being seen.

As Bastiat put it: “Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference—the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen and also of those which it is necessary to foresee.”

Of course, politicians are in the business of winning elections not in the business of foreseeing or in the business of practicing good economics.

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on January 12, 2016