Sometime in August last year I got an email, late in the evening. Before I clicked to open it, I thought it was one of the many spam emails that one gets during the course of any day.

Thankfully, I did click on it and the contents of the email told me that it wasn’t spam. The sender of the email was writing a book and he wanted my permission to refer to an article I had written for the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) in August 2013.

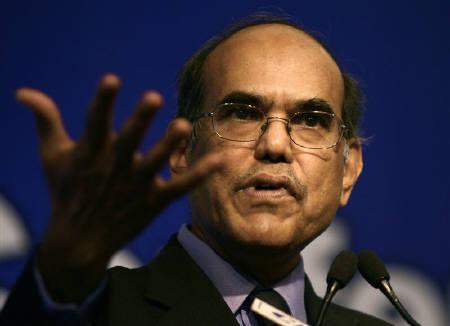

This book, which refers to my DNA article, titled Who Moved My Interest Rate? has recently published. It has been authored by D Subbarao, who was the governor of the Reserve Bank of India between 2008 and 2013, before Raghuram Rajan took over.

On page 140 of the book, governor Subbarao refers to my August 2013 DNA article. The article was titled RBI is behaving like a football goalkeeper. The article was written during the taper tantrum.

On May 22, 2013, Ben Bernanke, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve of the United States, the American central bank, told the Joint Economic Committee of the American Congress that “if we see continued improvement and we have confidence that that is going to be sustained, then we could in the next few meetings … take a step down in our pace of purchases.”

The Federal Reserve of the United States had been printing dollars every month. It had been pumping those dollars into the financial system by buying financial securities. The idea was to ensure that there was enough money going around in the financial system, so that interest rates remained low.

At lower interest rates, it was hoped that the American consumer would borrow and spend again, and in the process revive the economy. What also happened was that low interest rates allowed financial institutions to borrow dollars and invest them in financial markets all over the world. This became the dollar carry trade.

This led to financial markets rallying all over the world. Bernanke, spoilt the party in May 2013. What he was basically saying was that money printing by the Federal Reserve would come to an end. Of course, this wouldn’t be done all at once and would be done gradually (i.e. tapered) over a period of time. This meant that the dollar carry trade would no longer be viable with an era of easy money coming to an end and the interest rates starting to go up. And as a reaction institutional investors who had borrowed in dollars to invest, started to get money out of financial markets all over the world.

This included India. Foreign investors sold both stocks and bonds. When they did that, they got rupees in exchange. These rupees had to be exchanged for dollars, if the money was to be repatriated back to the United States. This pushed up the demand for the dollar, and the rupee started to lose value against the dollar.

In fact, on May 22, 2013, when Bernanke made his comment one dollar was worth Rs 55.41. By August 7, 2013, when my article appeared in DNA, one dollar was worth Rs 60.78. Of course, the RBI was trying to intervene in the foreign exchange market in order to ensure that rupee doesn’t fall too much.

One of the major reasons for doing the same lay in the fact that those were days of high oil prices. India imports four-fifth of the oil that it consumes. Hence, the oil companies would have to pay more in rupees to buy the dollars that they would have needed to buy oil.

Further, back then the oil companies weren’t allowed to pass on this increase in price of oil to the end consumer by increasing the price of diesel, kerosene and cooking gas (since then diesel has gone out of the list). The government picked up a major part of this tab and in the process the fiscal deficit of the government went up as well. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

Getting back to the point. In my DNA article I suggested that the RBI was behaving like a football goal keeper. This analogy came from a research note written by Societe Generale’s Albert Edwards. In this note, Edwards said: “When there are problems, our instinct is not just to stand there but to do something… When a goalkeeper tries to save a penalty, he almost invariably dives either to the right or the left. He will stay in the centre only 6.3% of the time. However, the penalty taker is just as likely (28.7% of the time) to blast the ball straight in front of him as to hit it to the right or left. Thus goalkeepers, to play the percentages, should stay where they are about a third of the time. They would make more saves.”

But they rarely do that. “Because it is more embarrassing to stand there and watch the ball hit the back of the net than to do something (such as dive to the right) and watch the ball hit the back of the net,” wrote Edwards.

The point being that in a moment of crisis it is important to be seen to be doing something. Using this analogy, I had said that the RBI would have been better off just letting the rupee fall and finding its right level. The efforts of the RBI between May and August hadn’t helped much, and the rupee had continued to fall. As I wrote back then: “The RBI is like a football goalkeeper. It knows ‘do nothing’ is the best course, but it can’t just stand pat.”

This is something that Subbarao also suggests in his book. As he writes: “Let me conclude my experiences of steering the rupee in turbulent waters by reiterating a standard dilemma. Given my position that a sharp correction of the exchange rate was programmed and forex intervention by the Reserve Bank would only postpone the inevitable, wouldn’t it have been rational to just stay put till the adjustment had been complete…Sensible maybe, but virtually impossible in the shrill democracies of today.”

To conclude, this is a point that another ex-RBI governor (not Subbarao) made to me once, when he said that in “moment of crisis the central bank can’t be seen to be doing nothing,” even if “do nothing” might be the best strategy to follow.

The column was originally published in Vivek Kaul’s Diary on July 18, 2016